The struggle over history is never merely about preservation or scholarship. It is a struggle over legitimacy, authority, and the limits of power.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Memory as a Political Technology

Political power has never rested solely on armies, laws, or administrative reach. It also depends on how societies understand their past. Collective memory shapes what feels natural, what seems legitimate, and what alternatives can even be imagined. For this reason, history is not merely inherited by states; it is actively curated, framed, and at times suppressed. Control over memory functions as a form of governance, one that operates quietly but decisively by shaping the horizon of political possibility.

States that seek unity, especially after periods of fragmentation or conflict, often encounter a fundamental problem: the past is plural. Multiple traditions, rival moral frameworks, and competing historical narratives offer citizens ways to judge the present against earlier alternatives. That capacity for comparison is dangerous to regimes that claim inevitability or moral finality. When people can see that things were once otherwise, they can imagine that they might be otherwise again. The management of historical memory thus becomes a strategy for narrowing political imagination.

The earliest large-scale example of this strategy appears not in the modern nation-state but in ancient imperial China. During the unification of China under the Qin, the state did not merely consolidate territory, law, and administrative authority; it attempted to consolidate time itself. The inherited past, with its competing dynastic memories and moral traditions, represented a destabilizing force. Historical texts preserved models of rule that emphasized virtue, restraint, and moral reciprocity, offering implicit critiques of coercive authority. By suppressing those traditions, the Qin sought to sever the link between memory and moral evaluation. What survived was not an empty historical landscape, but a carefully pruned one in which the past existed only to affirm present power.

This effort was neither anti-intellectual nor indiscriminate. Technical manuals, legal codes, and practical knowledge were largely spared, revealing the regime’s priorities with unusual clarity. What threatened the Qin was not knowledge itself, but comparison. Competing histories allowed subjects to measure the present against alternative pasts and to judge rulers according to standards not defined by the state. By narrowing historical memory, the regime aimed to make its authority appear self-evident and exclusive. What follows argues that such suppression operates as a political technology rather than an act of cultural destruction. From Qin China to modern conflicts over museums, curricula, and public history, the underlying logic remains consistent. When history is filtered to eliminate discomfort, the state becomes the hero of its own narrative, legitimacy is insulated from scrutiny, and the future is quietly constrained by a past that no longer offers meaningful alternatives.

The Qin Unification and the Problem of the Past

The unification of China in the third century BCE solved a military problem while creating a profound ideological one. For centuries, the Warring States had competed not only through force but through rival claims about proper rule, moral authority, and historical legitimacy. Each state preserved its own traditions, chronicles, and exemplary pasts, often embedded in local ritual practice and elite education. These histories did more than record events. They supplied moral vocabulary, political expectations, and standards of judgment. When the Qin conquered these rivals and imposed a single political order, it inherited not a blank slate but a densely layered historical landscape filled with competing memories that did not automatically converge into unity. Military victory unified territory, but it did not unify meaning.

Unification intensified, rather than resolved, the problem of legitimacy. Conquest could compel obedience, but it could not easily command assent. The newly unified empire encompassed populations accustomed to judging rulers against earlier dynasties, legendary sages, and regional moral traditions. Historical precedent mattered deeply in Chinese political culture. The past functioned as a reservoir of models for governance and as a moral court of appeal. In such a context, centralized authority faced constant implicit comparison, one that threatened to undermine claims of inevitability or finality.

For the Qin, this posed a structural danger. If subjects could invoke earlier rulers who governed differently, more gently, or more virtuously, then the present regime appeared contingent rather than necessary. The plurality of historical memory preserved the idea that power could take multiple forms and that coercive rule was neither timeless nor unavoidable. The past thus became a political liability. It offered standards external to the state by which authority could be measured and found wanting.

The solution adopted by the Qin did not involve rewriting history in the modern sense, nor did it rely primarily on persuasion or reinterpretation. Instead, the regime moved to eliminate the conditions under which comparison could occur at all. By narrowing the range of accessible historical narratives, the state aimed to prevent memory from functioning as a tool of critique rather than to refute specific arguments. The problem was not that the past existed, but that too many pasts existed simultaneously. Unification therefore required not only administrative standardization of weights, measures, and laws, but historical compression. To govern the present securely, the Qin concluded, the past itself had to be disciplined, reduced, and brought into alignment with the authority of the new imperial order.

Qin Dynasty and the Burning of the Books

The policy commonly known as the burning of the books emerged from the Qin court as a calculated response to the problem of historical plurality. According to later historical accounts, the edict associated with the policy was issued during the reign of Qin Shi Huang and enforced through the imperial bureaucracy. Its purpose was not to eradicate literacy or learning, but to regulate which forms of knowledge could circulate publicly. In a newly unified empire, texts that preserved rival historical traditions or moral frameworks represented a threat to ideological consolidation.

The scope of the destruction was selective rather than total. Texts associated with Confucian moral philosophy, historical chronicles of earlier states, and writings that encouraged ethical comparison between rulers were targeted for elimination. By contrast, works on medicine, agriculture, divination, and practical administration were largely exempt. This distinction reveals the logic of the policy. Knowledge that enhanced state capacity or technical efficiency was preserved, while knowledge that enabled moral judgment or political critique was removed. The aim was to protect governance from scrutiny grounded in precedent rather than to suppress intellectual activity as such.

This selectivity underscores a crucial point often lost in popular retellings. The Qin state did not seek to create an ignorant population. It sought to create a population whose historical awareness was confined to narratives compatible with imperial authority. By eliminating texts that preserved alternative visions of order, virtue, or restraint, the regime attempted to sever the relationship between memory and evaluation. Subjects would still know the past, but only a past filtered through the priorities of the present state.

The burning of the books therefore functioned as an act of historical filtration rather than cultural annihilation. The Qin aimed to prevent the circulation of texts that allowed people to ask comparative questions. How did earlier rulers govern? What moral obligations constrained power? Could authority be exercised differently. Such questions destabilized a regime that grounded legitimacy in unity, obedience, and legal uniformity rather than ethical persuasion? By removing the textual foundations that sustained these inquiries, the state sought to limit not only dissent but the very habit of moral comparison. The policy worked by narrowing the intellectual field until alternative standards of judgment became difficult to articulate, let alone defend.

The policy reveals a sophisticated understanding of political psychology and institutional control. By managing memory, the Qin reduced its reliance on constant force and surveillance. Authority could operate more smoothly when the past itself appeared to endorse the present order. Control over narrative diminished the need for overt repression by shaping what subjects regarded as normal, possible, and legitimate. The burning of the books was thus not an episodic excess or symbolic cruelty, but a central component of imperial strategy. It aligned historical consciousness with state power, transforming memory into an instrument of governance and reinforcing the illusion that the Qin order was not merely dominant, but historically inevitable.

Selective Memory, Not Ignorance

The Qin book burnings are often misunderstood as an attempt to plunge society into ignorance, a dramatic gesture of intellectual destruction driven by fear of knowledge itself. This interpretation mistakes absence for intention and spectacle for strategy. The regime did not seek to dismantle learning or to produce an uninformed population incapable of administration or productivity. On the contrary, Qin governance depended on educated officials, standardized procedures, and technical competence. Ignorance would have undermined state capacity rather than strengthened it. What the Qin opposed was not knowledge in general, but uncontrolled memory. Ignorance weakens states by reducing their ability to function. Selective memory strengthens them by reducing the range of political and moral comparisons available to their subjects.

By allowing technical, legal, and divinatory texts to survive, the Qin demonstrated a deliberate distinction between useful knowledge and dangerous knowledge. Works related to agriculture, medicine, engineering, law, and prognostication were preserved because they enhanced the practical effectiveness of the state and supported bureaucratic governance. Historical chronicles and moral philosophy, by contrast, preserved narratives that existed outside the authority of the new imperial order. These texts did more than recount events. They encoded ethical expectations, political limits, and models of virtuous rule that allowed subjects to evaluate rulers rather than simply obey them. The danger lay not in literacy or learning, but in the capacity of historical memory to serve as an external standard of judgment.

Selective memory operates by narrowing the range of acceptable reference points. When only one version of the past circulates, it becomes increasingly difficult to articulate dissent without appearing irrational or disloyal. The state does not need to argue against alternative histories if those histories are no longer accessible. The absence of comparison reshapes political imagination. Authority appears natural rather than contingent, and obedience appears prudent rather than coerced. The past ceases to function as a resource for critique and becomes instead a backdrop that silently endorses present power.

This strategy reveals why historical suppression is more effective than overt censorship alone. Censorship reacts to challenges as they arise. Selective memory prevents them from forming. By disciplining what can be remembered, the Qin sought to discipline how people thought about power itself. History remained present, but only in a form that affirmed unity, legality, and imperial permanence. The result was not an ignorant society, but one whose understanding of the past had been carefully filtered to support the authority of the state.

Obedience, Unity, and the Moral Vacuum

The suppression of historical plurality under the Qin did more than manage memory. It reshaped the ethical architecture of governance itself. When moral philosophy and comparative history were removed from public circulation, obedience ceased to be one civic virtue among others and became the central expectation of political life. Unity, narrowly defined as compliance with centralized authority, displaced moral deliberation as the foundation of order. This was not a passive consequence of censorship but an intentional recalibration of values. By removing the means through which subjects could evaluate power ethically, the regime ensured that political loyalty was measured by conformity rather than judgment. What emerged was not simply ideological conformity, but a systematic hollowing out of moral discourse in public life.

This transformation aligned closely with Legalist political thought, which rejected moral persuasion as unreliable, subjective, and potentially destabilizing. Legalist theorists such as Han Feizi argued that effective rule depended on uniform laws, predictable rewards, and severe punishments rather than appeals to virtue or conscience. In this framework, moral reasoning was not merely unnecessary but actively dangerous. Ethical debate encouraged disagreement, and disagreement fractured unity. The Qin state absorbed this logic at an institutional level, treating moral plurality as a structural threat rather than a civic strength. By privileging law over ethics and procedure over persuasion, the regime transformed governance into a system that functioned independently of moral consent.

By eliminating texts that articulated alternative moral standards, the regime created a vacuum in which law stood alone. Authority no longer needed to justify itself according to inherited ethical norms because those norms had been rendered inaccessible. Obedience was reframed as rational self-preservation within a system of rewards and punishments, not as participation in a shared moral project. Unity was achieved not through consensus, but through the absence of legitimate alternatives. In such a system, compliance appeared prudent rather than coerced, even as the ethical basis of authority thinned.

The moral vacuum created by this strategy had significant consequences for political culture. Without publicly available standards by which rulers could be judged, criticism lost its language. Resistance could still occur, but it lacked an ethical vocabulary capable of challenging authority on its own terms. Dissent became either criminal or incoherent, stripped of the historical precedents that might have legitimized it. The state did not need to refute moral arguments because it had removed the conditions under which such arguments could be sustained.

This configuration reveals the deeper function of selective memory within authoritarian systems. Historical suppression does not merely silence the past; it restructures the moral relationship between ruler and subject. When unity is defined as obedience and obedience is detached from ethical evaluation, authority becomes procedural rather than principled. Power persists through compliance rather than legitimacy. The Qin did not eliminate morality entirely, but relocated moral judgment exclusively within the state itself, leaving no external standard by which authority could be assessed. What remained was order without accountability, unity without deliberation, and obedience unmoored from any independent measure of right and wrong.

Collapse, Restoration, and the Return of Memory

The Qin project of disciplined memory proved powerful, but it was also brittle. The same mechanisms that narrowed historical imagination and suppressed moral critique contributed to the regime’s inability to absorb stress, dissent, or failure. By stripping authority of ethical depth and reducing legitimacy to procedural obedience, the state deprived itself of symbolic flexibility. When crises emerged, there was no shared moral language through which sacrifice could be justified or hardship meaningfully explained. Authority rested almost entirely on enforcement, leaving little room for resilience once coercion reached its limits.

The rapid collapse of the Qin following the death of Qin Shi Huang exposed the limits of rule built on selective memory. Without a shared moral narrative to bind ruler and subject, the state disintegrated quickly under pressure. Rebellions drew strength not only from material grievances but from the absence of any persuasive justification for continued obedience. The Qin had succeeded in narrowing the past, but in doing so had also narrowed the future. When the coercive apparatus faltered, there was little left to sustain allegiance.

The succeeding regime confronted this failure directly. The early Han rulers recognized that imperial authority could not rest on legal uniformity and force alone. In rebuilding the state, they undertook a deliberate restoration of suppressed traditions, especially Confucian moral philosophy and historical scholarship. The revival of classical texts was not an antiquarian gesture. It was a political strategy aimed at reestablishing a moral vocabulary through which authority could be justified, criticized, and ultimately legitimized. Memory returned as a stabilizing force rather than a threat.

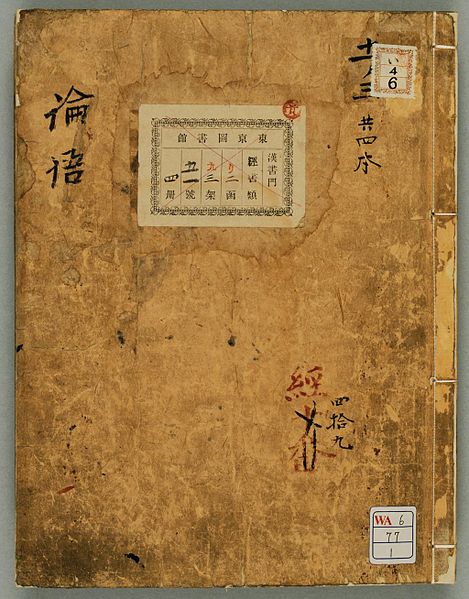

Under the Han, historical writing was actively encouraged, culminating in comprehensive projects such as Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian. These works did more than chronicle events. They reintroduced comparison, precedent, and moral evaluation into political culture, allowing rulers to be measured against earlier figures and dynastic standards. Praise and condemnation alike became possible once again. This did not weaken imperial authority. It strengthened it by embedding power within a longer moral continuum. By accepting judgment from the past, the Han regime gained credibility in the present and continuity into the future.

The Qin experience demonstrates a recurring pattern in the politics of memory. Historical suppression can produce short-term unity, but it undermines the deeper foundations of authority by severing power from ethical continuity. When coercion replaces persuasion and obedience replaces legitimacy, regimes become efficient but unstable. The restoration of memory under the Han did not reverse unification or decentralize power. It recalibrated authority by reconnecting governance to standards that existed beyond immediate state interest. Suppressed histories rarely disappear. They endure, preserved in fragments and recollections, waiting for the moment when power once again requires moral grounding to survive.

Preventing Comparison in the Modern State

Modern states rarely burn books, yet the logic that animated Qin suppression has not disappeared. Instead, it has been refined and institutionalized through subtler mechanisms of control. Contemporary governments operate within environments saturated with information, making total erasure impractical and counterproductive. The modern strategy is not to eliminate history, but to manage its presentation. By shaping curricula, funding priorities, museum narratives, and commemorative practices, states can narrow historical memory without appearing to censor it. The result is a curated past that feels comprehensive while quietly excluding destabilizing comparisons.

Educational systems provide one of the most effective arenas for this form of memory management. Decisions about what is emphasized, minimized, or omitted determine which historical trajectories students are encouraged to recognize. When uncomfortable episodes are reframed as marginal, anomalous, or irrelevant, the past loses its capacity to challenge the present. Complexity gives way to coherence, and coherence favors authority. This is not ignorance by accident. It is selectivity by design, ensuring that historical knowledge reinforces civic loyalty rather than moral scrutiny.

Museums and public history institutions play a parallel role. Exhibits that foreground national triumph while downplaying injustice or dissent present a narrative of continuity and virtue that resists comparison. The goal is not to deny that conflict or wrongdoing occurred, but to isolate such moments from broader patterns. By removing context, historical disruptions lose their explanatory power. Visitors encounter a past that confirms national identity rather than interrogates it. As in the Qin case, the danger lies not in falsehood alone, but in the elimination of relational understanding across time.

The underlying objective remains consistent across eras. Comparison threatens authority because it reveals contingency. When citizens can see that societies have organized power differently, justified authority differently, and resolved conflict differently, present arrangements appear neither inevitable nor permanent. Preventing comparison therefore stabilizes power by constraining imagination. Modern states do not need to destroy historical texts to achieve this end. They need only ensure that alternative pasts remain fragmented, marginalized, or inaccessible. The politics of memory continues, not through flames, but through frameworks.

Why Memory Threatens Power

Historical memory threatens power because it destabilizes claims of inevitability. Authority seeks to present itself as natural, necessary, and continuous, while memory exposes contingency. The past reveals that institutions have taken different forms, justified themselves through different moral languages, and collapsed under conditions that once appeared stable. When citizens are able to situate the present within a broader temporal frame, power loses its aura of permanence. What appears fixed becomes provisional. What claims necessity becomes subject to judgment.

Memory also threatens power by enabling comparison, and comparison produces evaluation. Historical knowledge allows people to measure rulers against predecessors, policies against alternatives, and outcomes against earlier choices. This evaluative function is deeply unsettling to regimes that depend on compliance rather than consent. Comparison invites questions that cannot be answered by procedure alone. Why was authority exercised differently before. What constraints once existed. What obligations were expected of rulers. Such questions do not require rebellion to be dangerous. They require only recognition.

Beyond comparison, memory sustains moral continuity. Ethical standards rarely arise fully formed in the present. They are inherited, debated, revised, and transmitted across generations. When historical traditions remain accessible, they supply external benchmarks by which power can be assessed. Authority must then justify itself not only in terms of efficiency or security, but in terms of moral legitimacy. Selective memory interrupts this process by severing the chain through which ethical reasoning travels. By isolating the present from inherited standards, regimes avoid moral accounting without openly rejecting morality itself. What remains is governance that appears value-neutral while quietly exempting itself from ethical comparison.

Memory also threatens power because it preserves the record of failure. Official narratives tend toward triumph, coherence, and progress, smoothing over contradiction to project stability. History, when fully accessible, records misjudgment, excess, and collapse alongside achievement. It documents how confident regimes dismissed warnings, silenced critics, and misunderstood the conditions of their own endurance. Such recollection weakens the persuasive force of authority by reminding citizens that strength and certainty are not safeguards against decline. Memory reintroduces humility into political life by demonstrating that power has failed before, often for reasons that were visible but ignored at the time.

Finally, memory threatens power because it expands political imagination. Knowledge of alternative pasts widens the range of conceivable futures. When people recognize that institutions have been organized differently, justified differently, and constrained differently, the present loses its monopoly on possibility. Suppressed histories do not merely inform. They cultivate the capacity to imagine otherwise. This is why regimes that fear instability so often target historians, educators, archivists, and curators. Memory does not prescribe action, but it restores the sense that change is conceivable. Power endures most comfortably when the past appears singular and closed. It becomes vulnerable when memory reopens time and returns the future to human choice.

Conclusion: The Past as a Battleground

The struggle over history is never merely about preservation or scholarship. It is a struggle over legitimacy, authority, and the limits of power. From Qin China to the modern state, regimes that seek unquestioned unity have repeatedly identified the past as a threat rather than a resource. History, when allowed to remain plural and accessible, undermines claims of inevitability by exposing contingency. It reminds societies that power has taken many forms, justified itself through many moral languages, and failed under conditions once assumed to be permanent. For this reason, the past becomes a battleground whenever authority seeks insulation from judgment.

The Qin experience demonstrates with unusual clarity that historical suppression is not an act of ignorance, but of deliberate design. By narrowing memory, the state attempted to narrow imagination, foreclosing comparison in order to stabilize obedience. This strategy proved effective in the short term, producing procedural unity and administrative efficiency across a newly unified empire. Yet that very efficiency concealed a deeper fragility. When power is severed from ethical continuity and historical accountability, it loses the capacity to adapt, persuade, and endure. Coercion can enforce order, but it cannot supply meaning. The collapse of the Qin revealed the cost of governing without memory as a shared moral resource, exposing how quickly authority dissolves when fear is no longer sufficient to sustain allegiance.

The restoration of historical traditions under the Han illustrates the inverse lesson. Authority became more durable, not weaker, when it reaccepted judgment from the past. By reintegrating moral philosophy and historical comparison into political culture, the state regained ethical depth and symbolic flexibility. Memory did not fragment power. It stabilized it by reconnecting governance to standards that transcended immediate interest. The return of history allowed authority to be evaluated, criticized, and ultimately affirmed within a longer temporal continuum. Power endured because it was no longer isolated from meaning.

The persistence of these dynamics into the present underscores the continuing relevance of the Qin model. Modern states may no longer burn books, but they still shape memory by managing curricula, museum exhibits, archives, and public narratives. The aim remains familiar: prevent comparison, preserve myth, and secure legitimacy without accountability. Uncomfortable histories are reframed, isolated, or quietly removed from public visibility, not to erase knowledge entirely, but to weaken its critical force. Yet history resists permanent enclosure. Suppressed pasts endure in fragments, testimonies, and records, waiting for moments when power once again requires moral grounding. The past cannot be permanently conquered. It can only be contested, and in that contest lies the enduring possibility of judgment, imagination, and choice.

Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah. Between Past and Future. New York: Viking Press, 1961.

- Assmann, Jan. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Connerton, Paul. How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Graham, A. C. Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. La Salle, IL: Open Court, 1989.

- Han Feizi. Han Feizi: Basic Writings. Translated by Burton Watson. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003.

- Lewis, Mark Edward. The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Liu, Sunxiaozheng. “Exploring the Reasons for the Rapid Demise of the Qin Dynasty.” International Conference on Advances in Social Sciences and Sustainable Development (2022): 272-276.

- Liu, Ziqi and Donghui Song. “Analysis of the Rise and Fall of the Qin Dynasty in Relation to Legalism.” Communications in Humanities Research 4:1 (2023): 359-366.

- Loewe, Michael, and Edward L. Shaughnessy, eds. The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Nora, Pierre. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire.” Representations 26 (1989): 7–24.

- Pines, Yuri. Envisioning Eternal Empire: Chinese Political Thought of the Warring States Era. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2008.

- Sima Qian. Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji). Translated selections in Burton Watson, Records of the Grand Historian of China. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961.

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 2015.

- Wertsch, James. V. and Henry L. Roediger III. “Collective Memory: Conceptual Foundations and Theoretical Approaches.” Memory 16:3 (2008): 318-326.

- Yang, Tony Zirui. “Normalization of Censorship: Evidence from China.” The Journal of Politics 87:4 (2025).

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.30.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.