Examining some curious glimpses of early American frontier life, Cambridge-style.

By Dr. Karl S. Guthke

Kuno Francke Professor of German Art and Culture, Emeritus

Harvard University

The Migration of Intellectuals

Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century1 demographic events such as the “clearances” in Scotland, the potato famine in Ireland and the pogroms in Eastern Europe all had a significant impact on the national composition of the immigrant population of North America. However, the significance of these events tends to overshadow the fact that individual intellectuals, too, left their mark on the profile of its people, long before the influx of the 1848ers after the failed German revolution. Indeed, the very first generation of settlers, in both centers of immigration, Virginia and New England, is remarkable among colonial populations for its considerable component of university men. Whether scholars or gentlemen or both, they were determined to leave an intellectual legacy. As early as 1619, ten thousand acres were set aside for a college in Henrico, Virginia, designed to teach the Indians “true religion and civil course of life”;2 and the college in the “other” Cambridge bears the name of the Cantabrigian who bequeathed his more than 300 books to it in the 1630s.3 “These university-trained emigrants were the people who founded the intellectual traditions and scholastic standards […]. They created that public opinion which insisted on sound schooling, at whatever cost; and through their own characters and lives they inculcated, among a pioneer people, a respect for learning.”4 The earliest settlers of Virginia, from 1607 on, were cultured if nothing else, and the “Great Migration” of some 13,000 by-and-large reasonably prosperous Puritans to New England during the 1630s included 118 university men, an estimated 85 percent of them clergy. About three quarters of them were Cambridge graduates. Sidney Sussex College, which is featured in this essay as a representative sample, with four graduates coming to America in the 1630s, contributed its fair share, comparable to other Cambridge colleges, say, Pembroke, Clare and King’s, though not to Emmanuel, which sent no fewer than thirty-five alumni to New England by 1645, virtually all of them during the 1630s. (Far fewer university men had emigrated to New England before 1630.)5

Typically, all four Sidney men were clergymen. Yet while three of them, George Burdett, George Moxon, and John Wheelwright, left Old England for the New to escape various forms of alienation and oppression commonly inflicted on Puritans in the pre-Commonwealth era, the fourth, Thomas Harrison, came to Virginia as a High Church man, but moved from Anglican Virginia to nonconformist Boston as a newly reborn Puritan, having become persona non grata in the colony of Cavaliers. But he was by no means the only one of the four reverends who ran afoul of religious orthodoxy. In fact, each of the other three had his difficulties with the Puritan orthodoxies that emerged rapidly in the colony designed to be the Almighty’s kingdom on transatlantic Earth. Oddly enough — or perhaps not — both Virginia and New England, each in her denominationally separate way, created the same climate of religious intolerance, oppression, and harassment that many of the university men had found unbearable at home, when Archbishop Laud reigned supreme, imposing Arminian “popery” on recalcitrant Calvinists.6 No wonder all four Sidney graduates were among those — nearly half of the intellectuals, ministers, and university men who had embarked on the “errand into the wilderness” of New England out of a sense of mission — who returned to England from 1640 on, until 1660 when the tide turned with respect to opportunities for both political action and clerical employment.7 While around 1630, according to Captain Roger Clap, “How shall we go to Heaven” was a more popular topic of discourse than “How shall we go to England,”8 the reverse seems to have been true a decade later. By that time, Heaven had all but been established in the Boston area, but Old England was widely considered “the more tolerant country,” as one remigrant put it.9

In the metaphoric language of the Statutes of Sidney Sussex College, the four men I shall examine more closely were no doubt the bees that swarmed the farthest from their hive in their search for new habitats (“ita ut tandem ex Collegio, quasi alveari evolantes, novas in quibus se exonerent sedes appetant”).10 Was it a worthwhile trip? And what manner of bees were they? Not the drones (“fuci”), surely, which the Statutes providentially included in their extended simile, but a very mixed lot, nonetheless. That is the short answer. The slightly longer one offers some curious glimpses of American frontier life, Cambridge-style.

A Puritan in Anglican Virginia

Thomas Harrison arrived in North America in the very year, 1640, when the remigration of Puritans began in a statistically significant way—a symbolic coincidence perhaps, since he came as a Church of England divine; the standard reference works, Venn’s Alumni Cantabrigienses, A. G. Matthews’s Calamy Revised, Alumni Dublinenses, W. Urwick’s Early History of Trinity College Dublin, and other authorities all state or imply that he came as chaplain to Virginia’s governor, the scholar and playwright Sir William Berkeley. But this is hardly possible as Berkeley did not set foot on the colonial shore until 1642, while the inhabitants of Virginia’s Lower Norfolk County chose Thomas Harrison as their minister “at a Court Held 25th May 1640,” offering him an annual salary of one hundred pounds.11 Whether he did eventually become Berkeley’s chaplain, as rumor has it, is highly doubtful.12 What is recorded is only that he was the minister of Elizabeth River Parish and later (concurrently?) of nearby Nansemond Parish from 1640 until 1648.13 Who was he? The Sidney Sussex College Records give us a relatively full picture of his background:

[1634] Thomas Harrison Eboracensis filius Roberti Harrison Mercatoris natus Kingstoniae super Hull, et ibidem literis grammaticis institutus in Schola communi sub M[agist]ro Jacobo Burney per quinquennium, dein ibidem sub M[agist]ro Antonio Stephenson per biennium adolescens annorum 16 admissus est pensionarius ad convictum Scholarium discipulorum Apr: 12. Tut. Ri. Dugard SS. Theol. Bacc. solvitq[ue] pro ingressu.14

According to Venn, he received his B.A. in 1638. What he did during the next two years is not known. Nor are we well informed about his doings during the early years in Virginia, other than that the Lower Norfolk County Records show that in 1645 he received a fee of one thousand pounds of tobacco, then worth five pounds sterling, for conducting the burial service over the graves of Mr. and Mrs. Sewell of Lower Norfolk and delivering a sermon in their memory.15 By this time, however, he had done Sidney’s intellectual heritage proud in a more spiritual way. In April 1645 the County Court registered a complaint against him for nonconformity. The church wardens of his parish:

have exhibited there presentment against Mr. Thomas Harrison Clark (Parson of the Said parish) for not reading the booke of Common Prayer and for not administring the Sacrament of Baptisme according to the Cannons and order prescribed and for not Catechising on Sunnedayes in the afternoone according to Act of Assembly upon wch prsentmt the Court doth order that the Said Mr. Thomas Harrison shall have notice thereof and bee Summoned by the sherriffe to make his psonall appearaunce at James Citty before the Right worrl [sic] the Governor & Counsell on the first daye of the next Quarter Court and then and there to answere to the Said prsentment.16

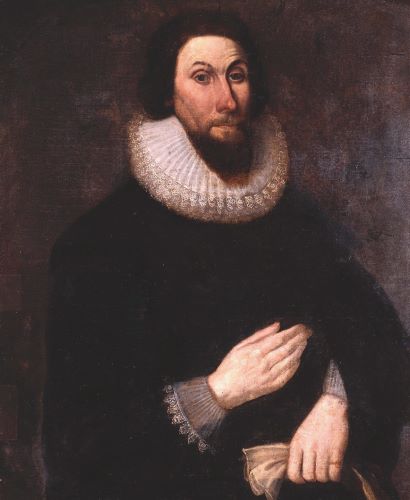

Harrison’s conversion to Puritanism had a distinctly New World flavor. For it seems to have taken place under the impression of the 1644 massacre of white settlers by Indians led by Chief Opechancanough, which in Puritan circles was widely held to be God’s retribution for the persecution of Puritans in Virginia.17 By 1647, when the Virginia Assembly under Berkeley had passed an act declaring that ministers refusing to read the Book of Common Prayer were no longer entitled to receive their parishioners’ tithes,18 Harrison’s position was officially heretic. He made no bones about this himself in three letters written between 1646 and 1648 to Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop. The initial contact between the two men is no doubt connected with the presence of three Puritan pastors from Massachusetts in Virginia, sent there by Winthrop in 1642 at the request of local dissenters, but obliged to return the following year.19 Writing on 2 November 1646, Harrison thanks Winthrop profusely for an unspecified “signall favour” which must indicate at least spiritual support; he also says that Winthrop has encouraged him to “giue you an account of our matters,” and assures him of his willingness to “seke and take directions (and if you please commands) from you.”20 On 14 January 1648 he proudly announces, amid a hodgepodge of political news from Old England, “74 haue ioyned here in Fellowship, 19 stand propounded, and many more of great hopes and expectations.”21 At home, Charles’s kingdom still, the Levellers are cause for concern, as he tells the Governor of his spiritual home-in-exile on 10 April 1648; all the more reason to rejoice that the true Kingdom lies to the West: “Sir whether it be true or false, the Saints in these goings downe of the Sun had never more light to see why their Father hath thus farre removed them, nor ever more strong engagements to be thainkfull for it.”22

With these sentiments, Harrison’s days in Virginia were numbered. He was banished from the colony in the summer of 1648. By October, he “is cam to boston.”23 As Adam Winthrop writes to his brother John, Jr. at the Pequod plantation on 1 November 1648: “Mr. Harrison the Paster of the church at verienya being banished from thence is arrived heer to consult about some place to settle him selfe and his church some thinke that youer plantation will be the fittst place for him, but I suppose you haue heard more amply before this.”24

Opposition against Harrison’s banishment for not conforming to the Book of Common Prayer soon arose not only among Harrison’s parishioners and in the Virginia Council of State but also in Cromwell’s Whitehall.25 To the latter’s protest there was a staunchly loyalist reply in March, 1651: “’Tis true, indeed, Two Factious clergy men chose rather to leave the country than to take the oaths of Allegeance and Supremacy, and we acknowledge that we gladly parted with them.”26

The case was still not settled in July, 1652.27 But by that time, Harrison could probably not have cared less. In 1651 he had assumed the ministry at Dunstan-in-the-East in London, “a large and important parish. Oliver Cromwell was occasionally before him as he preached.”28 Eventually, when Henry Cromwell became Commander-in-Chief of the Irish army, Harrison became his Chaplain, and his career continued with distinction until his death in Dublin in 1682.29

Personally, Harrison seems to have been the most pleasant of the four Sidneyans in America. According to Calamy:

he was extreamly popular, and this stirr’d up much Envy. He was a most agreeable Preacher, and had a peculiar way of insinuating himself into the Affections of his Hearers; and yet us’d to write all that he deliver’d: and afterwards took a great deal of Pains to impress what he had committed to Writing upon his Mind, that he might in the Pulpit deliver it Memoriter. He had also an extraordinary Gift in Prayer; being noted for such a marvellous fluency, and peculiar Flights of Spiritual Rhetorick, suiting any particular Occasions and Circumstances, as were to the Admiration of all that knew him. He was a compleat Gentleman, much Courted for his Conversation; free with the meanest, and yet fit Company for the greatest Persons. My Lord Thomund (who had no great Respect for Ecclesiasticks of any sort) declar’d his singular value of the Doctor, and would often discover an high Esteem of his abilities. He often us’d to say, that he had rather hear Dr. Harrison say Grace over an Egg, than hear the Bishops Pray and Preach.30

A Troublemaker in New England

It is doubtful whether George Burdett, on the other hand, could have said grace over an egg without risking scandal — as with everything he did, or didn’t. No reference to him, whether in documents of the time or in assessments by colonial historians, fails to mention his remarkable consistency in objectionable behavior. Perhaps this is why there is no trace of him in the Sidney Sussex College records. A discreet form of academic disowning? Still, less purist sources, Venn among them (pt.1, I, 256), indulge their passion for completeness by including the man who, coming to Cambridge from Trinity College, Dublin, was admitted to Sidney in 1623–1624 where, on an unknown date, he must have acquired the M.A. that is attributed to the troublemaker extraordinaire in reference works such as Frederick Lewis Weis, The Colonial Clergy and the Colonial Churches of New England (Lancaster, Mass., 1936, 46) and Anne Laurence, Parliamentary Army Chaplains, 1642–1651 (Woodbridge, 1990, 105). Venn, to be sure, stands on academic nicety and volunteers no more than a grudging “called M.A.,” as though giving Burdett more than he deserved.

Venn’s curt “was constantly in trouble” understates the case, however, as it refers only to Burdett’s years in America. As a matter of record, Burdett was well on his way to his later image while still in England. Admittedly, he was batting on a sticky wicket. From 1632 to 1635 he was a Puritan “Lecturer” (the formal designation of a “town preacher”) in the coastal town of Great Yarmouth.31 Here, as in much of East Anglia (even before the Arminian Bishop Matthew Wren of Norwich was installed in 1636 as Archbishop Laud’s watchdog) nonconformists with strong feelings about predestination versus the beneficial power of the sacraments had a particularly difficult time. Indeed, many Puritan ministers embarked for New England from that very port.32 Burdett’s early brush with ecclesiastical authority is amply documented in the Acts of the Court of High Commission (which also reveal that in the six or so years before coming to Great Yarmouth, between 1626 and 1632, he had been preaching in no fewer than three parishes: Brightwell, Saffron Walden, and Havering33—perhaps indicative of a rolling stone gathering no moss, but no sympathy either). In any case, in Great Yarmouth, the records in the Calendar of State Papers indicate that trouble flared up between the Lecturer and his Curate, Matthew Brookes, almost immediately after Burdett arrived. The charges of spiritual deviancy range from “blasphemy” to “raising new doctrines,” from “not bowing at the name of Jesus” to unorthodox views on redemption and Communion, from which he wished to exclude whoremongers and drunkards. (He was himself accused of being at least one of these later.) The Court of High Commission suspended him in February 1635. By July that year “his poor wife” petitioned for an annuity for the support of herself and their children, her husband “being gone for New England.”34

Burdett had sailed to Salem, Massachusetts, from where in December that year he wrote to Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury, complaining about the circumstances leading to his “voluntary exile.”35 This is interesting in connection with a later letter (1638) to Laud, which has given rise not only to the accusation that he was Laud’s emissary, spying on the unorthodoxies of New England, but also that he had only “pretended” to quarrel with the ecclesiastical authorities at home in order to be all the safer in his contemplated subversive role overseas.36 While the Court records leave no doubt about his protracted conflict with his ecclesiastical superiors in Laudian England, there is no denying that the man who was “held in high esteem” in Puritan Salem, where he was admitted as a freeman of the colony and given a piece of land “upon the rock beyond Mr. Endecott’s fence,”37 did ingratiate himself to the arch enemy of all Puritans a little later. This was after he had moved, again as a preacher, in 1637, to the settlement called Pascataqua[ck], now Dover, New Hampshire. From this safe haven he denounced Massachusetts in 1638 in at least three letters to Archbishop Laud for unorthodox thinking and seditious plotting.38 Somehow John Winthrop, the Governor of Massachusetts (already nettled by “a scornful answer” he had received earlier that year from Burdett in reply to his remonstrances about Pascataquack harboring residents “we had cast out”),39 got wind of the matter, and a serious matter it was, “discovering what they [Burdett and an associate] knew of our combination to resist any authority, that should come out of England against us.”40 As Winthrop explained the case himself,

one of Pascataquack, having opportunity to go into Mr. Burdet his study, and finding there the copy of his letter to the archbishops, sent it to the governour, which was to this effect: That he did delay to go into England, because he would fully inform himself of the state of the people here in regard of allegiance; and that it was not discipline that was now so much aimed at, as sovereignty; and that it was accounted [perjury] and treason in our general courts to speak of appeals to the king.

The first ships, which came this year, brought him letters from the archbishops and the lords commissioners for plantations, wherein they gave him thanks for his care of his majesty’s service, &c. and that they would take a time to redress such disorders as he had informed them of, &c. but, by reason of the much business now lay upon them, they could not, at present, accomplish his desire. These letters lay above fourteen days in the bay, and some moved the governour to open them; but himself and others of the council thought it not safe to meddle with them, nor would take any notice of them; and it fell out well, by Gods good providence; for the letters (by some means) were opened, (yet without any of their privity or consent,) and Mr. Burdett threatened to complain of it to the lords; and afterwards we had knowledge of the contents of them by some of his own friends.41

But Burdett seems to have been a man of such irrepressible propensity for making enemies that even without the Laud/Winthrop connection he managed to make himself unpopular in Dover almost from the start. “He aspired to be a sort of Pope,” one local historian says.42 If not pope, then at least spiritual and administrative leader, preacher and “governor.” Historians disagree on whether Burdett’s personal failings contributed to his leaving Dover after no more than two years (see n. 41 and n. 37). In any case, by 1639 he had once again changed places and provinces: he now served as minister43 in Agamenticus, Maine (presently York), and here the scandal which appears to have been brewing just below the surface of earlier documents broke out with full fury.

“It would seem that he no longer preached,” in the judgment of the distinguished Massachusetts historian Charles Francis Adams, based on a variety of early accounts, “as selecting for his companions ‘the wretchedest people of the country,’ he passed his leisure time ‘in drinkinge, dauncinge [and] singinge scurrulous songes.’ He had, in fact, ‘let loose the reigns of liberty to his lusts, [so] that he grew very notorious for his pride and adultery.’ At Agamenticus, also, Deputy-Governor Gorges found the Lords Proprietors’ buildings, — which had cost a large sum of money, and were intended to serve as a sort of government house, — not only dilapidated but thoroughly stripped, ‘nothing of his household stuff remaining but an old pot, a pair of tongs, and a couple of cob-irons.’”44

The Province and Court Records of Maine do indeed paint a picture of the final stage of Burdett’s errand into the wilderness which is not pretty, but all the more colorful. While his offences in Dover, according to Governor Winthrop, included, at least by implication, doctrinal deviations, the court in Saco, Maine, in 1640 dealt with issues of this world. Burdett brought at least three suits of slander against some of his neighbors who alleged sexual escapades with one George Puddington’s wife “and that his bed was usually tumbled” (I, 71). In the event, he was “indicted by the whole bench for a man of ill name and fame, infamous for incontinency, a publisher and broacher of divers dangerous speeches the better to seduce that weake sex of women to his incontinent practises” and fined a total of forty-five pounds for “entertaining” Mrs. Puddington, breaking the peace and “deflowring Ruth the wife of John Gouch” (I, 74–75). By 9 September 1640 he is already the “late minister of Agamenticus” (I, 77), and the last we hear about him in the records is: “Richard Colt sworne and examined saith that he heard John Baker say he heard John Gouch say that he was minded to shoote Mr. Burdett, but that his wife perswaded him to the contrary, and further that he heard the said Baker say that he thought the said John Gouch carryed a pistoll in his pockett to shoote Mr. Burdett” (I, 80).

Winthrop thought he had the last word: “Upon this Mr. Burdett went into England, but when he came there he found the state so changed, as his hopes were frustrated, and he, after taking part with the cavaliers, was committed to prison.”45 But there was life after prison. Under Charles II, Burdett became Chancellor and Dean of the diocese of Leighlin, Ireland.

A Saintly Preacher in the Wild West of Massachusetts

From the most obnoxious to the least troublesome — George Moxon, a farmer’s son, born in Wakefield, whose entry in Sidney’s Admissions Register (MR. 30) reads:

Georgius Moxon Eboracensis filius Jacobi Moxon agricolae, natus in paroecia de Wakefield, educatus ibidem in publico literaru[m] ludo sub praeceptore Mro. Izack per annu[m] adolescens annu[m] aetatis agens decimu[m] octauu[m]: admissus est in Collegium pauper scholaris Junij 6. 1620. Tutore & fideiussore Mro. Bell. (159)

According to Venn (pt.1, III, 225), he received his B.A. in 1624, was ordained in 1626 and appointed to the perpetual curacy of St Helen’s, Chester. Perpetual was a respectable dozen years; not until 1637 was he cited for nonconformity over disuse of the ceremonies, and he lost no time embarking from Bristol in disguise. He turned up in Dorchester, near Boston, the same year. Here Moxon was admitted as a freeman on 7 September.46 Very soon thereafter, William Pynchon, the founder of the trading post in Springfield, then called Agawam, must have persuaded Moxon to join his year-old Puritan settlement and spread the gospel in the Wild West of Massachusetts. He arrived early in 1638 “at the season of general thanksgiving through New England at the overthrow of the Pequots.” By “the spring of 1638 it had been voted that the expenses of fencing his home-lot on the main street and of building his house should fall upon those who might join the plantation thereafter.”47 From then on, until Moxon’s return to England in 1652, one hears nothing but his praises sung. His “sermons were of love,” if on the curiously pragmatic ground that “we are in a new country, and here we must be happy, for if we are not happy ourselves we cannot make others happy.”48 “Others” do not seem to have included the Indians, though, for the Rev. Moxon is on record as having opined that an Indian promise is “noe more than to have a pigg by the taile.”49 With this exception, his charity was boundless, for in his sermons he would cover “about all that could be said upon his subject, dividing and subdividing his topic with reckless prodigality of time”—with the then predictable result that, as Pynchon wrote to Governor Winthrop in 1644, “the Lord has greately blessed mr. Moxons ministry.”50 And to this day the man who brought such happiness remains fixed in local memory as he was described in a poetical portrait written shortly after his return to England:

As thou with strong and able parts are made,

The person stout, with toyle and labor shall,

With help of Christ, through difficulties wade.51

He did have difficulties in Western Massachusetts. In part they were of this world, such as the suit for unspecified slander brought by Moxon against one John Woodcock in December 1639, in which he demanded £9 19s in damages and, with three of his witnesses sitting on the jury, due to the scarcity of upright citizens in what was then “the interior,” got no more than £6 13s 4d, even though Woodcock declared that he was ready to repeat the offence.52 Spiritual malaise erupted when both of Moxon’s daughters started having “fits,” which suggested traffic with the devil. While tiny, the outpost was large enough to have a male witch in residence: Hugh Parsons, he of the red coat, who was tried for witchcraft in Boston in 1651 along with his wife, Mary. Still, by this time Moxon was well enough ensconced spiritually to weather the storm. A forty-foot-long meeting house had been built for his congregation in 1645, and the following year “it was agreed with John Matthews to beat the drum for the meetings at 10 of the clock on lecture days and at 9 of the clock on the Lord’s days, in the forenoon only, from Mr. Moxon’s to Rowland Stebins — from near Vernon Street to Union Street, and for which ‘he is to have 6 pence in wampum, of every family, or a pick of Indian corn, if they have not wampum.’”53

Real — and that meant doctrinal in Massachusetts at the time — “difficulty” did however loom large at about the time when the Parsons were tried for witchcraft in Boston. Moxon’s sponsor and mentor, the local squire William Pynchon, no mean theologian himself, had published a book in 1650 entitled The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption, Justification, etc. The General Court of Massachusetts had the book burned as heretical and directed the author to appear at its next meeting, 14 October 1651, to retract his errors. Pynchon and his wife left the colony instead, sometime in 1652. “With them went the Reverend George Moxon [whose Puritan orthodoxy had been officially suspect to Boston divines as early as 1649]54 who, as Pynchon’s sympathizer and spiritual adviser, must have known that his turn to be questioned, censured, and ejected would come next.”55

Moxon’s afterlife in England was auspicious at first: he shared the Rectory of Astbury, Cheshire, with one George Machin and was made Assistant Commissioner to the “Triers,” the examining board for prospective ministers appointed by Cromwell to make sure that candidates did not encourage dancing or playacting, or speak irreverently of Puritans.56 His luck did not outlast the Commonwealth by long, however. When the Act of Uniformity was passed in 1662, Moxon was removed from his post. The once popular minister was now reduced to preaching in barns and farmhouses. But there must have been consolation in the fact that he lived to see James II’s declaration of liberty of conscience, though he did not live to inaugurate the meeting house built for his congregation at Congleton, in the parish of Astbury.

A Champion of Spiritual Certainty among Hardline Puritans

Sidney’s graduate in America who looms largest in the early history of New England was the one of the four who returned to England only briefly, for a few years during the Commonwealth and early Restoration, and then all the more firmly transplanted himself to the New World, dying on the edge of the wilderness and leaving a family tree of many generations of descendants.57 This was John Wheelwright, the son of a Lincolnshire yeoman, born in 1594, two years before the founding of the College to which he was admitted on 28 April 1611 as a “Pensionar[ius],”58 earning his B.A. in 1614–1615 and his M.A. in 1618, according to Venn (pt.1, IV, 381). Ordained the following year, his career was true to form: suspended from his position as vicar at Bilsby, Lincs., in 1632, for alleged simony — which may have been his bishop’s way of getting rid of a nonconformist such as Wheelwright is assumed to have been (by Venn and others) — he left Old England for Massachusetts in 1636 after a brief spell as preacher at Belleau, Lincs.59 Whatever may ultimately have triggered his emigration, it was probably not the reissue of the Book of Sports in 1633, which encouraged sports on the Sabbath and drove many Puritans to distraction, or to Massachusetts.60 For one of the most enduring Sidney anecdotes has it, as Cotton Mather reported to George Vaughan, “that […] Cromwell, with whom he had been contemporary at the University, […] declared to the gentlemen about him ‘that he could remember the time when he had been more afraid of meeting Wheelwright at football, than of meeting any army since in the field; for he was infallibly sure of being tript up by him.’”61

In Boston, where he arrived on 26 May 1636, Wheelwright was tripped up himself soon enough in the field of Puritan doctrinal tackling which was just then hastening the climax of the game. While readily accepted into the Boston church and given the newly formed parish in the then somewhat outlying southern suburb of Mount Wollaston (now semi-metropolitan Braintree), this none too soft-spoken gentleman of the cloth was hardly off the boat before he got himself embroiled in the Antinomian controversy. Considering himself as Puritan as the next victim of English conformism, he nonetheless ran afoul of the Puritan orthodoxy which had, in the meantime, developed its own formula of indictable nonconformism on its virgin soil, which included Antinomianism. Leaving no hair unsplit, the Antinomians, most prominently Wheelwright’s voluble sister-in-law Ann Hutchinson, took the position that the real evidence of being “elected” by the Lord was not wealth and model civic and moral behavior, including good works, but the regenerate Christian’s spiritual certainty — something like a personal revelation of grace — which allowed the true believer to neglect sine-qua-non features of Puritan life such as church attendance and the massacre of Native Americans.62 Wheelwright came under official scrutiny in January 1637, after he preached a fast-day sermon in Boston in which he belligerently charged the ruling authorities with supporting a covenant of works rather than inner certainty of election. The General Court found him guilty of sedition and contempt of authority (right after settling a dispute about damage done by imported goats to neighbors’ crops) and later in the year disfranchised and “banished” him from the Bay Colony. He was given “14 dayes to settle his affaires,” while all those merely suspected of the Antinomian heresy were ordered to hand over “all such guns, pistols, swords, powder, shot, & match as they shal bee owners of” and one Rolfe Mousall, charged with having spoken “in approbation of Mr. Wheelwright, was dismissed from being a member of the Courte.”63

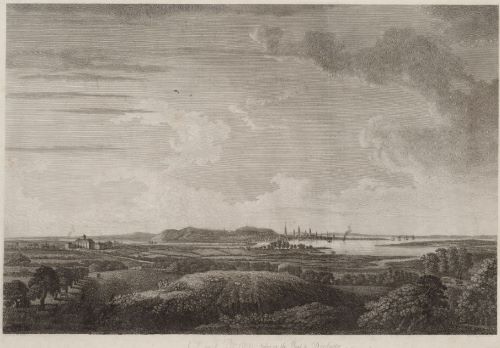

In November 1637 Wheelwright left for New Hampshire with a group of followers and became one of the founders of what is now Exeter. One of the attractions of the remote place must have been that since 1635 that colony “had been without any central government.”64 By the same token, when in 1643 Exeter came under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts, Wheelwright moved again, this time to Wells, Maine, perhaps the most outlying part of the New England wilderness. His voice, however, was heard here as he took his principal parishioners with him. Indeed, they became a sort of local aristocracy,65 if a tree-felling and log-cabin-building one. Whether it was the terminal boredom of this pioneer place or a surprising insight into his doctrinal error, we shall never know: in any case, in 1643, in two letters to Governor Winthrop, Wheelwright announced a change of heart about his Antinomianism, humbly requesting him to “pardon my boldness.”66 As a result, he had “his banishmte taken offe, & is reced in agayne as a membr of this colony,” the General Court of Massachusetts decreed the following year.67

If Wheelwright’s remorse was calculation rather than mid-life mellowing, it did not bear fruit immediately. It was not until 1647 that he was called to serve the Bay Colony again, at Hampton on the North Shore, and then only as an assistant to the pastor, as a mere “help in the worke of the Lord with […] Mr Dalton our prsent & faithfull Teacher,” as the contract specifies, which also assured him of a house-lot, a farm, and £40 per annum.68 In 1656 or 1657 Wheelwright left for England for what turned out to be no more than an extended interlude during which he met with his erstwhile college antagonist on the football field, “with whom,” he wrote to his Hampton parishioners on 20 April 1658, “I had discourse in private about the space of an hour,” arguably not limited to prowess in sports, as “all his [Cromwell’s] speeches seemed to me very orthodox and gracious.”69

So were Wheelwright’s by this time. His own church gave him a clean bill of doctrinal health. When in 1654 the pillars of Hampton saw fit to protest to the General Court that Wheelwright was being accused unfairly of heretical beliefs in Boston, they stated that he “hath for these many years approved himself a sound, orthodox, and profitable minister of the gospel,” and the General Court heartily agreed.70

After the Restoration the attraction of New England became irresistible once again. In 1662 we find Wheelwright tending a Puritan flock in Salisbury, in northern Massachusetts. Though he was at least close to retirement age by now, some of his belligerence was still virulent, or perhaps it reemerged in the form of the last-chance radicalism of the elderly. His relationship with the Magistrate of Salisbury, whom he excommunicated early on and then had to take back into the fold, was an armed truce at best. “Another argument between Pike [the Magistrate] and Wheelwright began on a Sunday evening when Pike was on his way to Boston. It was winter and he knew it would be a long trip. Pike was a Deputy of the General Court and had to be in Boston on Monday morning. Therefore, he decided to get an early start. As soon as the sun went down he started on his journey. After crossing the river though, the sun came back out. Reverend Wheelwright had Pike arrested for working on a Sunday, which was against the law. He accused Pike of knowing it was just a cloud passing over. Pike was fined ten shillings.”71

Such was life on the religious frontier. And Wheelwright made the most of it, plodding on in the service of the Lord until he was gathered to his spiritual fathers in 1679, in his mid-eighties then, but apparently still vigorously unretired, and the Salisbury Sabbath inviolate, changeable weather notwithstanding.

Summing Up

It was rather a mixed lot of pioneering bees, then, that swarmed to the end of the world from the far end of Bridge Street. What they said or did, or didn’t say or didn’t do, raised eyebrows then and adds color in retrospect. But, of course, such human shortcomings and foibles were the very foundation on which the Puritan theocracy of New England was built. Nobody this side of saintliness, not even a Cambridge-trained cleric, was excepted from that civic, moral, and doctrinal policing which such weaknesses and imperfections made so irresistibly desirable and which, in those early years, was the signal feature that distinguished New England from other British colonies. Still, though nil humani was missing in the four Sidney graduates, one thing not one of them was accused of was lax scholarship. Their alma mater need not disown them.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 2: “Errand into the Wilderness”: The American Careers of Some Cambridge Divines in the Pre-Commonwealth Era, from Exploring the Interior: Essays on Literary and Cultural History, by Karl S. Guthke, published by Open Book Publishers under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license.