By the late 1930s, the United States had completed its transformation from a nation of migration to a nation of enforcement. Immigration control had become a durable institution.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Constructing the “Undesirable”

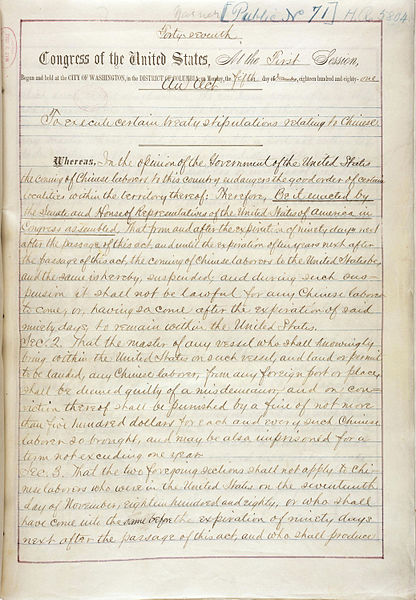

The closing decades of the nineteenth century marked the beginning of a fundamental transformation in the United States’ relationship to immigration. For much of the nation’s early history, newcomers had arrived with few formal restrictions, their movement governed more by circumstance than by law. Yet as the American population grew increasingly diverse and industrial society strained under the weight of urbanization, reformers and politicians alike began to question whether all who sought to enter could, or should, be welcomed. By 1882, Congress responded with the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first major piece of federal legislation to single out a specific group for exclusion on racial and national grounds. The same year saw the passage of the Immigration Act of 1882, which barred those deemed “idiots,” “lunatics,” and “convicts,” introducing a moral and medical logic to exclusion. In the decades that followed, this fusion of racial, mental, and moral judgment evolved into a bureaucratic machinery of control.1

The early twentieth century witnessed a growing fear that America’s openness endangered its social fabric. The First World War sharpened those anxieties into policy. The Immigration Act of 1917 imposed literacy tests, raised head taxes, and created the “Asiatic Barred Zone,” a geographic codification of racial hierarchy that aligned the United States with European empires in their exclusionary visions of global order. What had begun as piecemeal exclusion had by then become an ideological project: to preserve a particular conception of “American” identity rooted in whiteness and northern European ancestry.2

Between 1921 and 1924, this project reached legislative maturity. The Emergency Quota Act and the Immigration Act of 1924 limited entry from each nation in proportion to its representation in earlier U.S. censuses, effectively freezing the ethnic composition of the country as it stood in the late nineteenth century. These quotas, combined with the creation of the U.S. Border Patrol in 1924, marked the birth of a modern enforcement regime. Immigration officers now possessed institutional authority, armed resources, and racialized mandates that extended beyond ports of entry to the nation’s interior.3

The onset of the Great Depression deepened the cruelty of this system. As unemployment soared, state and federal authorities deported or coerced the departure of more than one million people of Mexican origin—many of them U.S. citizens, in a campaign of “repatriation” meant to protect white labor.4 These events revealed not merely administrative overreach but the moral logic at the core of early immigration enforcement: the belief that citizenship, belonging, and worth were contingent on race, productivity, and conformity to a narrowly defined American ideal.

What follows examines the evolution of U.S. immigration enforcement from the first exclusion laws of the late nineteenth century to the mass deportations of the 1930s. It argues that this period witnessed the creation of a racialized immigration state, one that transformed the abstract notion of “undesirable” people into a legal and bureaucratic category. The emergence of the Border Patrol, the implementation of quotas, and the weaponization of repatriation during economic crisis together established the architecture of control that continues to shape immigration policy today.

The Moral Architecture of Exclusion: 1882–1917

The legal foundation of American immigration enforcement was built upon moral judgment as much as it was upon economic or political reasoning. The earliest laws to regulate entry reflected a belief that certain individuals (by virtue of their perceived physical, mental, or moral defects) posed a threat to the national character. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 represented the first comprehensive federal law to prohibit immigration on the basis of race and nationality, singling out an entire ethnic group for exclusion. In doing so, it established a precedent: that Congress could define membership in the American polity not merely by allegiance or assimilation, but by race itself.5 The act was born of labor tensions, nativist agitation, and pseudoscientific notions of racial hierarchy, echoing the sentiment of Western politicians who argued that Chinese laborers were both unassimilable and corrosive to white wage labor.6

The Exclusion Act did not stand alone. The accompanying Immigration Act of 1882 empowered federal officials to deny entry to any person deemed a “convict, lunatic, idiot, or person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge.”7 In these categories lay the seeds of a broader ideology of moral exclusion, conflating physical disability, mental illness, and poverty with unworthiness. When the federal government centralized immigration inspection in 1891, it created the Bureau of Immigration within the Department of the Treasury, formalizing the process of moral judgment through bureaucratic procedure.8

Ellis Island, opened in 1892, became the theater of this new moral governance. Inspectors there acted as gatekeepers of national virtue, empowered to reject applicants on medical or moral grounds. Examinations sought signs of “mental defect,” criminality, or immoral behavior, including sexual promiscuity or political radicalism.9 What emerged was a form of social sorting that mirrored the eugenic thinking of the Progressive Era. Reformers such as Henry H. Goddard and Charles Davenport warned that admitting the “feeble-minded” or “degenerate” would pollute the national stock, a language that fused immigration control with biological determinism.10

By the early twentieth century, this fusion of morality and pseudo-science had taken on a distinctly national character. Immigration laws served as instruments of social engineering, promoting a vision of an industrious, white, Protestant America. The Immigration Act of 1903 expanded exclusions to anarchists and political radicals, linking ideology to moral degeneracy.11

The 1907 act established the Dillingham Commission, whose massive report, spanning more than forty volumes, claimed to demonstrate that newer immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe were less assimilable than earlier arrivals from Northern and Western Europe.12 This report laid the intellectual groundwork for the national origins quota system that would follow in the 1920s, providing a veneer of scientific legitimacy to what was fundamentally a racial hierarchy disguised as public policy.

Thus, by 1917, when Congress passed the first comprehensive immigration law imposing literacy tests and geographic exclusions, it did so upon decades of moralized exclusion. The American immigration state had evolved from local prejudice into institutional power. What began as a project to bar the “unfit” had matured into a mechanism to regulate national identity itself, defining who could be American not only by law, but by body, mind, and origin.

The Immigration Act of 1917: Literacy, Security, and the “Asiatic Barred Zone”

The Immigration Act of 1917 marked a decisive turn in U.S. immigration policy, transforming exclusion from a moral and racial project into one embedded within national security and geopolitics. The act, passed amid the global turbulence of the First World War, reflected deep anxieties about loyalty, radicalism, and the imagined fragility of the American nation. It was the first law to combine moral and racial exclusion with tools of bureaucratic enforcement on a global scale, introducing literacy tests, increasing head taxes, and defining vast regions of the world as categorically unfit for migration to the United States.13

The literacy test, requiring that immigrants over sixteen demonstrate the ability to read in any language, had been debated in Congress for over two decades, repeatedly vetoed by Presidents Grover Cleveland, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson. When it finally passed in 1917, over Wilson’s veto, it symbolized a triumph for restrictionists who framed literacy not simply as an indicator of education, but as a proxy for cultural and racial fitness.14 As historian Mae Ngai has observed, this measure functioned less to assess intelligence than to exclude impoverished laborers from Southern and Eastern Europe and colonial Asia, reinforcing hierarchies of civilization already embedded in global imperial thought.15

Just as consequential was the act’s creation of the “Asiatic Barred Zone,” stretching from the Middle East through South Asia and the Pacific Islands. This sweeping exclusion not only targeted Asian migration but codified a geopolitical understanding of race: the “East” as a civilizational boundary incompatible with the American body politic.16 The map of exclusion mirrored the logic of empire, aligning the United States with Britain and France in their colonial classifications of racialized labor. The 1917 law thus translated global racial geography into domestic immigration law.17

The context of wartime nationalism also infused the act with new security functions. In the wake of the Russian Revolution and mounting fears of anarchism, immigration control was increasingly linked to the surveillance of radical politics. The law expanded grounds for deportation to include “anarchists” and “subversive aliens,” conflating political dissent with national threat.18 The Bureau of Immigration, previously under the Department of Labor, now acted in concert with the newly formed Bureau of Investigation (the forerunner to the Federal Bureau of Investigation), marking the beginning of a relationship between immigration control and domestic security that would persist throughout the twentieth century.19

At the same time, the law reinforced class stratification through its financial provisions. The head tax, raised to eight dollars, was designed to limit poor migration under the guise of protecting American workers.20 The measure appealed to organized labor, particularly the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which argued that restricting immigration preserved wages and safeguarded white working-class interests.21 Yet many employers, especially in agriculture and industry, objected to these restrictions, fearing labor shortages. The debate over immigration thus became a proxy for the struggle between capital and labor, mediated by a state increasingly committed to defining citizenship through exclusion.22

By 1917, the architecture of modern immigration control was in place. The United States had institutionalized a system that combined racialized geography, class exclusion, and ideological policing within a single statutory framework. What had begun in 1882 as a series of ad hoc exclusions had evolved into a comprehensive regime of restriction, supported by a growing bureaucracy and justified by appeals to security, science, and national survival. The stage was set for the quota system of the 1920s, a project that would fuse these principles into a full-scale racial hierarchy of entry.

Quotas and Bureaucracy: 1921–1924

The restrictive momentum that gathered force during the First World War culminated in the early 1920s with the introduction of the quota system, a legislative framework that formalized racial hierarchy as national policy. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921, followed by the Immigration Act of 1924, transformed the administration of immigration from a moral and security matter into a demographic one. For the first time, the United States legally defined who could belong not simply through exclusionary categories but through statistical proportionality, reducing humanity to numbers derived from past censuses.23

The Emergency Quota Act limited annual immigration from any given country to three percent of the number of persons from that country residing in the United States according to the 1910 census. While framed as a temporary measure to restore “balance,” the act disproportionately favored Northern and Western Europeans while sharply curtailing migration from Southern and Eastern Europe.24 The result was an immigration system that preserved the nation’s pre-1890 ethnic composition under the guise of scientific neutrality.25 Policymakers justified this hierarchy through appeals to social science and national stability. The 1924 law reduced the quota to two percent and recalibrated it to the 1890 census, effectively shutting out millions of Italians, Poles, Jews, Greeks, and other groups who had dominated immigration in the preceding decades.26

Behind the numerical precision lay a moral project: to freeze the racial and cultural identity of the United States in time. Senator David Reed of Pennsylvania, co-author of the 1924 act, described it as an attempt to preserve the “American stock.”27 The legislation’s architects relied heavily on eugenic research and the Dillingham Commission’s earlier claims of “inferior races.”28 In effect, the quotas turned pseudo-scientific racism into statutory arithmetic.

The 1924 law also introduced a new institutional arm to enforce this vision, the United States Border Patrol. Established under the Labor Appropriations Act of 1924, the agency was tasked with preventing “illegal entry” between ports of inspection, particularly along the southern border.29 Its creation marked a turning point: immigration enforcement became not only administrative but territorial, extending the reach of the federal government to the physical landscape of the border itself.30 What had once been imagined as a symbolic frontier now became a militarized line of demarcation.

While European arrivals fell under quotas, Mexican migration initially remained numerically unrestricted, reflecting the agricultural industry’s reliance on seasonal labor.31 Yet the establishment of the Border Patrol soon brought heightened scrutiny and racialized policing to the U.S.-Mexico boundary. Patrolmen, often drawn from local sheriffs and military veterans, exercised broad discretion to search, detain, and deport.32 They enforced racial hierarchies that mirrored domestic segregation laws, treating Mexican laborers as indispensable yet perpetually suspect.33 This duality, dependence and exclusion, became a defining feature of U.S. immigration enforcement.

At the bureaucratic level, the 1924 act consolidated authority within the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Immigration, formalizing a hierarchy of administrative expertise. Immigration officers became civil servants with standardized training, rules, and procedures, marking the transition from moral arbiters to professional enforcers.34 This bureaucratization lent the system an aura of neutrality, even as it institutionalized racial bias. It also laid the administrative groundwork for later mass deportations during the Great Depression, demonstrating that the enforcement apparatus, once built, could easily be turned against any group deemed undesirable.

By the mid-1920s, the United States had constructed a comprehensive architecture of immigration control: numerical quotas grounded in racial ideology, a dedicated enforcement agency at its borders, and a bureaucratic state capable of administering exclusion with scientific precision. The modern immigration regime had been born, not merely as a response to demographic pressure, but as a deliberate act of nation-building through restriction.

Enforcement and Repatriation: The Great Depression Era

When the Great Depression struck in 1929, the machinery of immigration control built in the previous decade was swiftly turned inward. The same bureaucratic and racial frameworks that had justified excluding Europeans and Asians were now mobilized against Mexicans and Mexican Americans already residing within the United States. The federal government, joined by state and local authorities, launched mass deportation and “repatriation” campaigns that expelled more than a million people from the country during the 1930s, many of them U.S. citizens.35 What began as an economic measure to preserve jobs for “real Americans” became one of the most sweeping civil rights violations in modern U.S. history.

The origins of this policy lay in the collapse of the labor market. As unemployment soared, Mexican and Mexican American workers (especially in agriculture, mining, and manufacturing) became scapegoats for white job loss.36 City governments in Los Angeles, Detroit, and Chicago orchestrated deportation drives under the guise of “voluntary repatriation,” offering train tickets to Mexico while threatening arrest, welfare termination, or violence.37 Between 1931 and 1934, Los Angeles County alone deported an estimated 12,000 residents, roughly sixty percent of them U.S. citizens.38 The federal Bureau of Immigration coordinated similar efforts nationwide, relying on the newly professionalized enforcement system created by the 1924 Immigration Act and its expanded patrol forces.

The legal basis for these deportations was tenuous. Many removals occurred without formal hearings, warrants, or judicial oversight.39 Local officials exploited provisions of existing immigration laws that allowed deportation of those “likely to become a public charge” or who entered without inspection, a catchall justification easily applied to anyone of Mexican descent.40 The line between citizen and alien blurred under racial suspicion. Newspapers framed the mass removals as acts of charity, restoring the unemployed “to their native land.”41 Yet behind the euphemism of “repatriation” was coercion: a campaign driven by racism and austerity politics, legitimized by the apparatus of state power.

While most attention focused on the Southwest, similar actions occurred throughout the Midwest and Northeast. The Mexican community in Detroit, for instance, saw nearly half its population deported or pressured into “voluntary” return.42 Churches and civic groups protested the cruelty of these measures, but federal agencies largely ignored such appeals. The mass expulsions decimated families, disrupted communities, and erased generations of American-born children from the civic record.43

By the mid-1930s, as the Roosevelt administration sought to stabilize the economy through the New Deal, official deportation drives slowed, but the damage endured.44 The legacy of the repatriations extended beyond immediate suffering. They entrenched the notion that citizenship and belonging could be revoked in moments of crisis. The racialization of Mexicans as “alien labor” persisted even after many were invited back through the wartime Bracero Program of the 1940s, which again exploited them as temporary and expendable workers.45

In this way, the Great Depression did not merely reveal the cruelty of the early enforcement system, it confirmed its durability. The exclusionary state born in the 1880s, bureaucratized in the 1920s, and weaponized in the 1930s had proven its capacity to adapt to new targets and new crises. Immigration enforcement was no longer confined to the border; it had become a national project of racial discipline.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Early Enforcement

By the late 1930s, the United States had completed its transformation from a nation of migration to a nation of enforcement. Immigration control, once a patchwork of moral judgments and racial fears, had become a durable institution with laws, agencies, and ideologies capable of reproducing themselves long after the crises that spawned them. The creation of quotas, the establishment of the Border Patrol, and the mass deportations of the Great Depression together marked the full maturation of a racialized immigration state. What began with the Chinese Exclusion Act as an assertion of white labor’s protection evolved into a system of surveillance, exclusion, and removal, an architecture of power that defined not only who could enter, but who could belong.46

The persistence of these structures reflected their adaptability. Immigration law proved elastic enough to respond to shifting political climates: wartime suspicion, economic collapse, and social reform all reinforced the state’s capacity to police the boundaries of citizenship. The early statutes’ language (“undesirable,” “public charge,” “feeble-minded”) gave bureaucratic shape to anxieties about purity, productivity, and moral worth.47 Each generation of restrictionists claimed new rationales (first morality, then literacy, then security) but the underlying logic remained constant: the belief that national strength required exclusion.

The consequences extended beyond policy. The architecture of exclusion influenced American ideas of identity and belonging, normalizing the association between race and citizenship. The literacy tests and quotas of the early twentieth century anticipated the national security vetting and border militarization of the twenty-first. The very concept of the “illegal alien,” as Mae Ngai has argued, emerged from this period as a product of law itself, a category invented to sustain the illusion of control in a world of movement and migration.48 In that sense, illegality was not an inherent trait but a legal fiction created to justify surveillance and punishment.

The moral dimensions of these policies are as striking as their durability. During the Depression, Mexican Americans, citizens by birth, were expelled under the same logic once used to bar Chinese laborers and “lunatics.”49 In each case, exclusion functioned as a mirror of national insecurity. Rather than addressing structural inequality, the state externalized its failures onto racialized outsiders. Immigration enforcement became, in effect, a form of social management, an instrument to define the limits of empathy and the reach of law.

By tracing the evolution of immigration enforcement from the 1880s through the 1930s, one sees not a linear story of progress but a deepening entrenchment of racial hierarchy within the machinery of the state. The quotas, the Border Patrol, and the “repatriations” were not aberrations; they were expressions of a coherent worldview that equated order with exclusion. That worldview endures in the modern border regime, where legality remains entangled with race, labor, and fear. The challenge, as history shows, is not only to reform policy but to confront the ideas that built it, to reckon with the moral inheritance of an enforcement system born from exclusion and sustained by its silence.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Erika Lee, At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 5–7.

- Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 21–28.

- Daniel J. Tichenor, Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 143–149.

- Francisco E. Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez, Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 2–4.

- Lucy E. Salyer, Laws Harsh as Tigers: Chinese Immigrants and the Shaping of Modern Immigration Law (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 3–4.

- Erika Lee, At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 18–21.

- U.S. Congress, An Act to Regulate Immigration, 22 Stat. 214 (1882).

- Daniel J. Tichenor, Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 91.

- Alan M. Kraut, Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the “Immigrant Menace” (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 28–32.

- Henry H. Goddard, The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness (New York: Macmillan, 1912), 5–7; Charles B. Davenport, Heredity in Relation to Eugenics (New York: Henry Holt, 1911), 93–95.

- U.S. Congress, Immigration Act of 1903, 32 Stat. 1213.

- U.S. Immigration Commission (Dillingham Commission), Reports of the Immigration Commission, 61st Cong., 2d Sess., Senate Document No. 747 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1911), vol. 1, 40–43.

- Roger Daniels, Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004), 45–47.

- U.S. Congress, Immigration Act of 1917, 39 Stat. 874.

- Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 21–24.

- Erika Lee, At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 224–226.

- Nayan Shah, Stranger Intimacy: Contesting Race, Sexuality, and the Law in the North American West (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 190–192.

- U.S. Congress, Immigration Act of 1917, §19, 39 Stat. 874.

- Daniel J. Tichenor, Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 143–145.

- U.S. Bureau of Immigration, Annual Report of the Commissioner General of Immigration (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918), 10.

- American Federation of Labor, Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Federation of Labor (Washington, D.C.: AFL, 1917), 112–113.

- Aristide R. Zolberg, A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 247–249.

- Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 27–30.

- U.S. Congress, Emergency Quota Act of 1921, 42 Stat. 5.

- Aristide R. Zolberg, A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 268–270.

- U.S. Congress, Immigration Act of 1924, 43 Stat. 153.

- Congressional Record, 68th Cong., 1st Sess. (April 1924), 5861.

- U.S. Immigration Commission (Dillingham Commission), Reports of the Immigration Commission, 61st Cong., 2d Sess., Senate Document No. 747 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1911), vol. 1, 41–43.

- U.S. Department of Labor, Appropriations Act for 1925, 43 Stat. 240 (1924).

- Kelly Lytle Hernández, Migra!: A History of the U.S. Border Patrol (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 29–31.

- George J. Sánchez, Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 58–60.

- Kelly Lytle Hernández, Migra!, 33–35.

- Natalia Molina, Fit to Be Citizens? Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879–1939 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 112–115.

- Daniel J. Tichenor, Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 154–156.

- Francisco E. Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez, Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 2–4.

- George J. Sánchez, Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 84–86.

- Natalia Molina, Fit to Be Citizens? Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879–1939 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 158–160.

- Francisco E. Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez, Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 91–93.

- Kelly Lytle Hernández, Migra!: A History of the U.S. Border Patrol (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 56–58.

- U.S. Congress, Immigration Act of 1917, §3, 39 Stat. 874.

- Los Angeles Times, February 25, 1931, 3.

- Abraham Hoffman, Unwanted Mexican Americans in the Great Depression: Repatriation Pressures, 1929–1939 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1974), 71–73.

- Gilbert G. González, Mexican Consuls and Labor Organizing: Imperial Politics in the American Southwest (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999), 102–104.

- Daniel J. Tichenor, Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 163–165.

- Deborah Cohen, Braceros: Migrant Citizens and Transnational Subjects in the Postwar United States and Mexico (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 12–15.

- Roger Daniels, Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004), 72–75.

- Alan M. Kraut, Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the “Immigrant Menace” (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 35–37.

- Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 5–8.

- Francisco E. Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez, Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 118–121.

Bibliography

- American Federation of Labor. Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Federation of Labor. Washington, D.C.: AFL, 1917.

- Balderrama, Francisco E., and Raymond Rodríguez. Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995.

- Cohen, Deborah. Braceros: Migrant Citizens and Transnational Subjects in the Postwar United States and Mexico. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

- Congressional Record. 68th Cong., 1st Sess. (April 1924).

- Davenport, Charles B. Heredity in Relation to Eugenics. New York: Henry Holt, 1911.

- Daniels, Roger. Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882. New York: Hill and Wang, 2004.

- Goddard, Henry H. The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness. New York: Macmillan, 1912.

- González, Gilbert G. Mexican Consuls and Labor Organizing: Imperial Politics in the American Southwest. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999.

- Hernández, Kelly Lytle. Migra!: A History of the U.S. Border Patrol. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

- Hoffman, Abraham. Unwanted Mexican Americans in the Great Depression: Repatriation Pressures, 1929–1939. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1974.

- Kraut, Alan M. Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the “Immigrant Menace”. New York: Basic Books, 1994.

- Lee, Erika. At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Molina, Natalia. Fit to Be Citizens? Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879–1939. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

- Ngai, Mae M. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Salyer, Lucy E. Laws Harsh as Tigers: Chinese Immigrants and the Shaping of Modern Immigration Law. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

- Sánchez, George J. Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900–1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Shah, Nayan. Stranger Intimacy: Contesting Race, Sexuality, and the Law in the North American West. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

- Tichenor, Daniel J. Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- U.S. Bureau of Immigration. Annual Report of the Commissioner General of Immigration. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918.

- U.S. Congress. An Act to Regulate Immigration, 22 Stat. 214 (1882).

- ———. Immigration Act of 1903, 32 Stat. 1213.

- ———. Immigration Act of 1917, 39 Stat. 874.

- ———. Emergency Quota Act of 1921, 42 Stat. 5.

- ———. Immigration Act of 1924, 43 Stat. 153.

- ———. Appropriations Act for 1925, 43 Stat. 240 (1924).

- U.S. Immigration Commission (Dillingham Commission). Reports of the Immigration Commission. 61st Cong., 2d Sess., Senate Document No. 747. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1911.

- Zolberg, Aristide R. A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Los Angeles Times. February 25, 1931.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.14.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.