Introduction

In the 1850s, Chinese workers migrated to the United States, first to work in the gold mines, but also to take agricultural jobs, and factory work, especially in the garment industry. Chinese immigrants were particularly instrumental in building railroads in the American west, and as Chinese laborers grew successful in the United States, a number of them became entrepreneurs in their own right.

As the numbers of Chinese laborers increased, so did the strength of anti-Chinese sentiment among other workers in the American economy. The expanding popularity of Chinese exclusion finally resulted in legislation that aimed to limit future immigration of Chinese workers to the United States and threatened to sour diplomatic relations between the United States and China.

Why Did Americans Object to Chinese Immigration?

American objections to Chinese immigration took many forms and generally stemmed from economic and cultural tensions, as well as ethnic discrimination. Most Chinese laborers who came to the United States did so in order to send money back to China to support their families there. At the same time, they also had to repay loans to the Chinese merchants who paid their passage to America. These financial pressures left them little choice but to work for whatever wages they could. Non-Chinese laborers often required much higher wages to support their wives and children in the United States, and also generally had a stronger political standing to bargain for higher wages.

Therefore many of the non-Chinese workers in the United States came to resent the Chinese laborers, who might squeeze them out of their jobs. Furthermore, as with most immigrant communities, many Chinese settled in their own neighborhoods, and tales spread of Chinatowns as places where large numbers of Chinese men congregated to visit prostitutes, smoke opium, or gamble. Some advocates of anti-Chinese legislation therefore argued that admitting Chinese into the United States lowered the cultural and moral standards of American society. Others used a more overtly racist argument for limiting immigration from East Asia, and expressed concern about the integrity of American racial composition.

California State Government Passed Racist and Discriminatory Laws against Chinese Immigrants

To address these rising social tensions, from the 1850s through the 1870s the California state government passed a series of measures aimed at Chinese residents, ranging from requiring special licenses for Chinese businesses or workers to preventing naturalization. Because anti-Chinese discrimination and efforts to stop Chinese immigration violated the 1868 Burlingame-Seward Treaty with China, the federal government was able to negate much of this legislation.

Congress Passed a Bill Limiting Chinese Immigration

In 1879, advocates of immigration restriction succeeded in introducing and passing legislation in Congress to limit the number of Chinese arriving to fifteen per ship or vessel. Republican President Rutherford B. Hayes vetoed the bill because it violated U.S. treaty agreements with China. Nevertheless, it was still an important victory for advocates of exclusion. Democrats, led by supporters in the West, advocated for all-out exclusion of Chinese immigrants.

Although Republicans were largely sympathetic to western concerns, they were committed to a platform of free immigration. In order to placate the western states without offending China, President Hayes sought a revision of the Burlingame-Seward Treaty in which China agreed to limit immigration to the United States.

Negotiated Angell Treaty with China

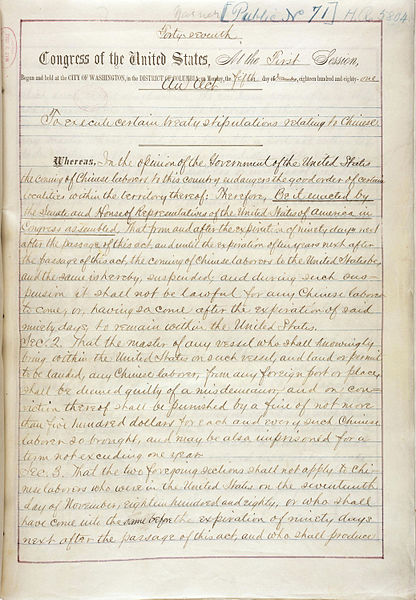

In 1880, the Hayes Administration appointed U.S. diplomat James B. Angell to negotiate a new treaty with China. The resulting Angell Treaty permitted the United States to restrict, but not completely prohibit, Chinese immigration. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which, per the terms of the Angell Treaty, suspended the immigration of Chinese laborers (skilled or unskilled) for a period of 10 years.

The Act also required every Chinese person traveling in or out of the country to carry a certificate identifying his or her status as a laborer, scholar, diplomat, or merchant. The 1882 Act was the first in American history to place broad restrictions on immigration.

Popularity Opinion Sought to Restrict Chinese Immigration Even Further

For American presidents and Congressmen addressing the question of Chinese exclusion, the challenge was to balance domestic attitudes and politics, which dictated an anti-Chinese policy, while maintaining good diplomatic relations with China, where exclusion would be seen as an affront and a violation of treaty promises. The domestic factors ultimately trumped international concerns. In 1888, Congress took exclusion even further and passed the Scott Act, which made reentry to the United States after a visit to China impossible, even for long-term legal residents.

The Chinese Government considered this act a direct insult, but was unable to prevent its passage. In 1892, Congress voted to renew exclusion for ten years in the Geary Act, and in 1902, the prohibition was expanded to cover Hawaii and the Philippines, all over strong objections from the Chinese Government and people. Congress later extended the Exclusion Act indefinitely.

In China, merchants responded to the humiliation of the exclusion acts by organizing an anti-American boycott in 1905. Though the movement was not sanctioned by the Chinese government, it received unofficial support in the early months. President Theodore Roosevelt recognized the boycott as a direct response to unfair American treatment of Chinese immigrants, but with American prestige at stake, he called for the Chinese government to suppress it. After five difficult months, Chinese merchants lost the impetus for the movement, and the boycott ended quietly.

The Repeal

In 1943, Congress passed a measure to repeal the discriminatory exclusion laws against Chinese immigrants and to establish an immigration quota for China of around 105 visas per year. As such, the Chinese were both the first to be excluded at the beginning of the era of immigration restriction and the first Asians to gain entry to the United States in the era of liberalization.

Repeal Was an Effort to Improve Relations with China during World War II

The repeal of this act was a decision almost wholly grounded in the exigencies of World War II, as Japanese propaganda made repeated reference to Chinese exclusion from the United States in order to weaken the ties between the United States and its ally, the Republic of China. The fact that in addition to general measures preventing Asian immigration, the Chinese were subject to their own, unique prohibition had long been a source of contention in Sino‑American relations.

There was little opposition to the repeal, because the United States already had in place a number of measures to ensure that, even without the Chinese Exclusion Laws explicitly forbidding Chinese immigration, Chinese still could not enter. The Immigration Act of 1924 stated that aliens ineligible for U.S. citizenship were not permitted to enter the United States, and this included the Chinese.

Proposed Elimination of the Ban against Chinese Immigration to the United States

More controversial than repeal was the proposal to go one step further and place the Chinese on a quota basis for future entry to the United States. By finally applying the formulas created in the 1924 Immigration Act, the total annual quota for Chinese immigrants to the United States (calculated as a percentage of the total population of people of Chinese origin living in the United States in 1920) would be around 105. In light of the overall immigration to the United States, at first glance the new quota seemed insignificant.

Yet, those concerned about an onslaught of Chinese (or Asian) immigration and its potential impact on American society and racial composition believed that even this small quota represented an opening wedge through which potentially thousands of Chinese could enter the United States. Because migration within the Western Hemisphere was not regulated by the quota system, it seemed possible that Chinese residents in Central and South America would re-migrate to the United States. Moreover, if the Chinese of Hong Kong were to apply under the vast, largely unused British quota, thousands could enter each year on top of the number of available Chinese visas.

Xenophobic Elements in the United States Feared a Flood of Chinese immigrants

Fears about the economic, social, and racial effect of a “floodtide” of Chinese immigrants led to a compromise bill—fears that mirrored the xenophobic arguments that had led to Chinese Exclusion in the first place, some sixty years previously. Under this bill, there would be a quota on Chinese immigration, but, unlike European quotas based on country of citizenship, the Chinese quota would be based on ethnicity.

Chinese immigrating to the United States from anywhere in the world would be counted against the Chinese quota, even if they had never been to China or had never held Chinese nationality. Creating this special, ethnic quota for the Chinese was a way for the United States to combat Japanese propaganda by proclaiming that Chinese were welcome, but at the same time, to ensure that only a limited number of Chinese actually entered the country.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt threw the weight of his office behind the compromise measure, connecting the importance of the measure to American wartime goals. In a letter to Congress, Roosevelt wrote that passing the bill was vital to correcting the “historic mistake” of Chinese exclusion, and he emphasized that the legislation was “important in the cause of winning the war and of establishing a secure peace.”

Conclusion

The repeal of Chinese exclusion paved the way for measures in 1946 to admit Filipino and Asian-Indian immigrants. The exclusion of both of these groups had long damaged U.S. relations with the Philippines and India. Eventually, Asian exclusion ended with the 1952 Immigration Act, although that Act followed the pattern of the Chinese quota and assigned racial, not national, quotas to all Asian immigrants. This system did not end until Congress did away with the National Origins quota system altogether in the Immigration Act of 1965.

Originally published by the Office of the Historian, United States Department of State, to the public domain.