By Arienne King

Introduction

From the peaceful reign of Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE), Rome’s first emperor, to the chaotic Year of the Five Emperors (69 CE), which culminated in the rise of the Flavian Dynasty, these were Rome’s first emperors, and all helped to shape the Roman Empire for better or worse.

Part of “Appearance of the Principate”, a larger series by Daniel Voshart, the photorealistic reconstructions in this collection are only best guesses at how their subjects may have appeared, based on literary and artistic evidence. Some artistic license has been taken to fill in certain details that can not be deduced from ancient sources. Made using Photoshop and Artbreeder, a neural net tool.

Images from Daniel Voshart at Voshart.com.

Augustus

Augustus (r. 27 BCE – 14 CE; Augustus, formerly known as Octavian, was Rome’s first emperor (ruled 27 BCE-14 CE), and his reign began the era of unprecedented peace known as the Pax Romana. Octavian was the adopted grand-nephew of Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE). Octavian rose to power as the unrivalled ruler of the Roman Empire after defeating his rival Mark Antony (83-30 BCE) in a civil war, and subsequently conquering Egypt. The Roman Senate gave him the title “Augustus” in 27 BCE, ushering in the beginning of the Roman Empire.

Pictured alongside the reconstruction are the busts and statuary used as references, including the Augustus of Prima Porta (top left), the Via Labicana Augustus (bottom left), and busts from the Pergamum Museum (top right), and the British Museum (bottom right).

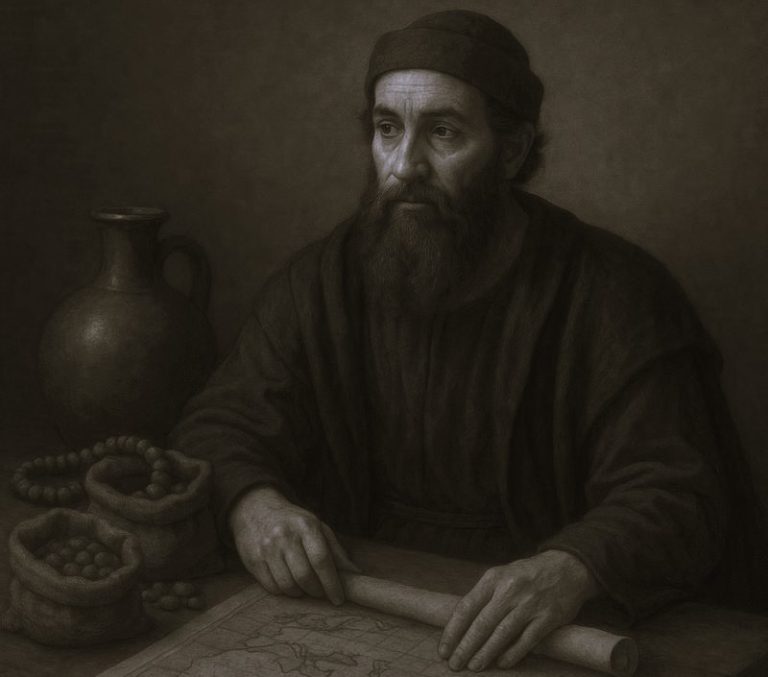

Tiberius

Tiberius (ruled 14-37 CE) was the stepson of Augustus and only became his heir after the deaths of Augustus’ grandchildren. Tiberius’ reign was more controversial than that of his predecessor, and his reputation less secure. In the later part of his reign, he increasingly succumbed to paranoia and reclusiveness. Roman historians painted him as a cruel tyrant, but his reign also brought wealth and peace to the young Roman Empire.

Pictured alongside the reconstruction are the busts and statuary used as references. From left to right and top to bottom these are the Carlsberg Glyptotek bust; Royal Ontario Museum bust; National Archaeological Museum bust; and the “Lansdowne Tiberius”.

Caligula

The reign of Caligula (ruled 37-41 CE) was plagued by scandals, both personal and political. Though he had some minor achievements – such as annexing the Kingdom of Mauretania – his reign was marked by frivolousness and cruelty. Caligula’s rule ended when he was killed by the Praetorian Guard, a death which foreshadowed the end of many Roman emperors.

This reconstruction is based on a single bust from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which is thought to be somewhat idealized. Traces of paint from surviving busts of Caligula are used as a reference for the color of his skin, hair, and eyes.

A more realistic and less idealized facial reconstruction of Caligula, based on multiple busts and sculptures which portray the emperor in a more human light. This depicts him with the flaws and imperfections that the real Caligula likely had. Similarly, some modern historians view the reign of Caligula in a more nuanced light, coming to the conclusion that his sadistic and unrestrained reputation was partly influenced by biases held by later emperors and historians.

The Louvre bust (top left) is the primary reference. The other references used are the Met Museum bust (bottom left) and the Museum of Rome bust (bottom right).

Claudius

Claudius (ruled 41-54 CE) was an unlikely emperor. During his early life, he was said to be feebleminded and infirm, but he later claimed that this was an act he maintained to avoid the wrath of Caligula. Whatever the truth of it, Claudius was a capable Roman emperor, albeit one easily manipulated by those close to him. During his reign, the borders of the Roman Empire expanded, and there was relative peace within it. Like his predecessors, Claudius was paranoid and quick to anger, executing many he felt were threats. He is thought to have been poisoned by his wife Agrippina (15-59 CE) so that her son Nero (r. 54-68 CE) could become emperor.

Pictured alongside the reconstruction are the busts and statuary used as references. From left to right and top to bottom these are the Naples National Archaeological Museum’s portrait; Claudius Pio-Clementino; Chiaramonti Claudius; and the National Archaeological Museum of Spain’s bust.

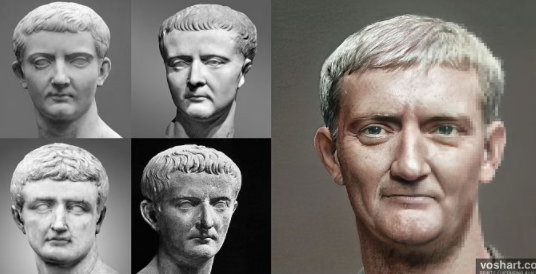

Nero

Nero (ruled 54-68 CE) was the last of the Julio-Claudian dynasty established by Augustus. He grew famous for his cruelty and hedonism, eventually becoming the archetypal violent, self-indulgent tyrant. Some historians have suggested that many tales about Nero’s bloodthirstiness and excess were exaggerated by a ruling class that disliked his populist policies and steep taxes. Some stories, like the claim that he fiddled while Rome burned, are probably best left to legend. Nero’s reign ended in bloodshed when a rebellious general overthrew him.

Pictured alongside the reconstruction are the artworks and statuary used as references. From left to right and top to bottom these are the Capitoline Nero; the Glyptothek bust; the Uffizi Gallery’s bust; and the painting by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640 CE). Although Rubens’ painting is a modern artwork and not a contemporary depiction of Nero, it has been included.

Galba

Galba, the governor of Hispania, led a revolt against Nero in 68 CE. Despite initially being branded an enemy of the state, the support of the Roman army allowed him to overthrow Nero. Galba, already an old man by the time he became emperor, was usurped by his one-time ally Otho in 69 CE. The end Galba’s short and violent reign proved to be just one episode in what became known as the Year of the Four Emperors.

Pictured alongside the reconstruction are the Capitoline bust of Galba and the bust from the Stockholm Museum of Antiquities, used as references for this reconstruction.

Otho

Otho (ruled 69 CE) took part in Galba’s usurpation of Nero after the latter banished him to Lusitania. Otho eventually betrayed Galba when the new Roman emperor chose another as his successor. He ruled only three months until the general Vitellius overthrew him.

Pictured alongside the reconstruction are the busts and artwork used as references. From left to right and top to bottom these are the Louvre bust; a painting by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640 CE); the British Museum bust; and the bust from the Uffizi Gallery. Although Rubens’ painting is a modern reimagining of Otho, it has been included.

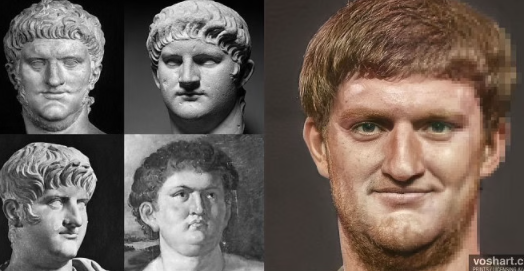

Vitellius

Vitellius ruled the Roman Empire for eight months in 69 CE, during which time he tried to adopt the populist image of Nero (r. 54-68 CE). He quickly came to be regarded as a cruel ruler after he began executing anyone he saw as a potential threat to his power. These actions only served to hasten his demise, as the army began to rally around a governor named Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE).

Pictured alongside the reconstruction are the artworks and statuary used as references. From left to right and top to bottom are the Louvre Pseudo-Vitellius; painting by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640 CE); Glyptotek bust; and the bust from the Rubens House in Antwerp.

Vespasian

Vespasian (ruled 69-79 CE) was the founder of the Flavian Dynasty (69-96 CE). He was the governor of Judea when Vitellius (r. 69 CE) came to power. As Vitellius became more reviled in Rome, the Roman armies in the East looked to Vespasian as their new emperor. Vespasian consolidated power and rapidly defeated Vitellius’ armies. With this, Vespasian ended the turmoil that had briefly threatened the Roman Empire. He ruled for ten years, until his death of natural causes at the age of 70. Both of Vespasian’s sons would in turn rule after him.

Pictured alongside the reconstruction are the artworks and statuary used as references. From left to right and top to bottom, these are the Louvre bust; Glyptotek bust; Capitoline bust; and the bust from the National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Titus

Titus (ruled 79-81 CE) was the son of Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE). Prior to becoming emperor, Titus was a commander in the Roman-Jewish War (66-73 CE). His forces sacked Jerusalem in 70 CE, tearing down the city walls and destroying the Second Temple of Jerusalem. After the death of Vespasian, Titus proved to be a capable and popular Roman emperor.

Pictured alongside the reconstruction are the artworks and statuary used as references. From left to right and top to bottom, these are the National Archaeological Museum of Naples bust; Archaeological Museum Théo Desplans bust; the British Museum bust; and a coin portrait of Titus.

Domitian

Domitian (ruled 81-96 CE) was the last emperor in the Flavian Dynasty. He became emperor after his brother Titus (r. 79-81 CE) died suddenly of natural causes, although poisoning by Domitian was also rumoured. He built numerous public works and monuments and oversaw the completion of the Colosseum (construction was begun in 72 CE during the reign of Vespasian and continued under Titus). His military record was mixed, resulting in a truce with the Kingdom of Dacia and Roman expansion into Britain. Domitian exercised more absolute power than his predecessors ever had, further diminishing what little power the Roman Senate had left. In later years, he became increasingly paranoid of conspirators until his assassination in 96 CE.

Pictured alongside the reconstruction are the artworks and statuary used as references. From left to right and top to bottom, these are the Vatican bust; Altes Museum Berlin bust; National Archaeological Museum of Venice bust; and the Louvre bust.

Originally published by the Ancient History Encyclopedia, 11.17.2020, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.