By Derek Litvak

PhD Candidate in History

University of Maryland – College Park

Abstract

The purpose of my project is to analyze how Virginians responded to the Intolerable Acts of 1774, which were mostly aimed towards Boston and Massachusetts. This analysis consists mainly of coal county and town resolutions passed during the summer of 1774 in response to the Intolerable Act. These resolutions reveal what many Virginian’s were thinking during this time as well as the evolution of their sentiments. Through these resolutions and other documents of the time, I was able to construct a portrait of the Virginia colonial mindset towards these acts, and how they eventually affected the overall colonial response. My results showed that these acts worked, inadvertently, towards unifying colonists against British policy. Their responses during this year are necessary in understanding the American Revolution.

Introduction

In short what further proofs are wanting to satisfy one of the designs of the ministry than their own acts…what hope then from petitioning, when they tell us that now or never is the time to fix the matter – shall we, after this, whine & cry for relief, when we have already tried it in vain?, Or shall we supinely sit and see one province after another fall a sacrifice to despotism?

George Washington to Bryan Fairfax, June 20, 1774

The story of the Intolerable Acts begins on the evening of December 16th 1773, when a group of Boston citizens dumped into the harbor more than 300 chests of tea that had arrived from Great Britain. The act of protest was meant to display the colonists’ apprehension to Parliament’s passage of the Tea Act, which seemingly allowed the British government to control free trade by giving the East India Company a monopoly on the commodity. Also tied to this, was the matter of Parliament’s right to tax the colonies, something that had been in dispute for years at this point. For the purposes of this paper, a detailed account of the Boston Tea Party is not necessary. What matters most, in this case, is Parliament’s response of passing a series of acts known as the Coercive Acts, which came to be known as the Intolerable Acts in America. Mostly aimed towards Boston and the colony of Massachusetts, these acts sparked widespread resentment and resistance across all of British America.1 Virginians, like many of their fellow subjects, came together in hopes that they could fight back against these acts, and defend their rights and liberties.

The Intolerable Acts of 1774 were composed of four separate acts. The first of these was the Boston Port, which closed the port, effective June 1st, by means of a blockade by the British Navy. Exportation from the port would be completely halted on that date, and importation would only be allowed for goods that were for the British troops, and the bare necessities needed by the inhabitants of the city. The port would open again only when the citizens of Boston had made full compensation to the East India Company for the tea that had been destroyed.2

The next of the acts was the Massachusetts Government Act. It effectively reshaped the entire structure of the Massachusetts government, by repealing the colony’s original charter. The act heavily restricted the number of town meetings, only allowing one meeting per year, unless the governor gave special permission. Since British officials saw the town meetings as a device used by radical Bostonians to push their agenda, the act dictated what business could occur at town meetings. Town meetings would only deal with things such as election of officials and other matters that the governor of Massachusetts expressly allowed. It also gave the governor an even larger amount of power. The upper house of the colonial assembly, which was previously elected, was replaced with members chosen by the king.3 All in all, the new Massachusetts government was only a vague shadow of what it had previously been.

The Administration of Justice Act was the third part of this set of acts. This act empowered the governor to move a trial of any government official to another colony, or even to Great Britain, if he believed that a fair trial could not occur in Massachusetts. A transfer was allowed in cases where a capital offense occurred in the execution of official duties. The act did allow, however, for the governor to transfer the trial of a person who wasn’t a government official, if they were working under the direction of a government official.4

The last of the Intolerable Acts was the Quartering Act, which, while aimed at Massachusetts like the other acts, could be implemented in all the colonies. It permitted the housing of British troops in uninhabited buildings if suitable housing could not be found for them. Unlike the commonly held view, however, the act did not allow, or suggest, for the housing of troops in the homes of private citizens. Housing would have most likely not been in a family’s house, but rather a warehouse that was not being used.5

A fifth act is often included in the Intolerable Acts, as it was viewed by the colonists as part of them. The Quebec Act, or Canada Act, had the misfortune of being passed at the same time as the Intolerable Acts, though it was not formally a part of them. The act enlarged the territory of Quebec to include areas north of the Ohio River. It also allowed for the continual free exercise of Catholicism in the colony, which had previously belonged to the French. The clergy were still allowed to collect a tithe, or tax, from the Catholic inhabitants. Along with this, French civil law, which didn’t include the right to a trial by jury, was allowed to continue. And a legislative assembly of appointed, not elected officials would also be created under the act.6

Historian David Ammerman’s book, In the Common Cause: American Response to the Coercive Acts of 1774, represents a comprehensive examination of the colonial response to the Intolerable Acts. Published in 1975, it is the only substantial work that provides an in-depth look at this topic. Readers of books on the American Revolution will likely see a relatively small number of pages dedicated to the Intolerable Acts, the colonial response, and will soon find themselves at the First Continental Congress. The months leading up to the First Continental Congress are often glossed over, as are the ones following.

The goal of this paper is to add to the current scholarship by shining a brighter light on the Virginian response to the Intolerable Acts. I have found that there is a stunning lack of attention given to this topic, which is clearly evident by the scarce amount of scholarship. Yet, by looking at what Virginians said themselves, through their resolutions, papers, letters, etc., one can create a vivid account of the Virginian response. The months leading to the First Continental Congress, and the ones after it, contain a wealth of knowledge of the Virginian attitude towards these acts. It is through all of this that I intend to show that Virginians began, more than ever, to form a sense of colonial unity, as well as push back against British policy with greater zeal.

The Initial Reactions

News reached Virginia about the Boston Port Act in late May of 1774. However, the news of the act put the House of Burgesses into a troubling dilemma. The Burgesses wished to make their position on the matter clear, knowing that the other colonies would look to Virginia for leadership. Virginia was the oldest of all the British American colonies, and was often viewed as the wise older sibling. John Cruger, speaker of the New York General Assembly, said in a letter to Peyton Randolph, speaker of the House of Burgesses, that Virginia was an “Ancient Colony and Dominion.” In comparison to her sister colonies, Virginia was also the largest and wealthiest of them all.7

Along with this, the other colonies recognized that Virginia’s support would not only be important, but influential at the same time. The Delaware Committee of Correspondence wrote to Virginia saying that the people of Delaware would listen to the colony’s opinion on the present affairs, as their resolutions would “have great Weight.” Virginia’s leadership in the developing affairs of British America would be crucial, and many people outside of the colony recognized that. Writing to Peyton Randolph, Charles Thomson of Philadelphia said that “All America look up to Virginia to take the lead on the present Occasion.” Compared to the other colonies, “None is so fit as Virginia. You are ancient, you are respected; you are animated in the cause.”8

The dilemma that arose for Virginia came from the fact that the representatives faced the possibility of the House being dissolved by the governor, Lord Dunmore, if they adopted any kind of stance against the new British policies. Having pressing matters to deal with in regards to the colony’s own affairs, the Burgesses didn’t want to be sent home before they could get any work done. However, knowing that the other colonies would look to Virginia for an answer, they felt the need to do something. On May 25th, the Burgesses made an attempt to find some sort of middle ground between not doing anything, and doing too much.9 The House adopted a resolution by Robert Carter Nicolas to turn June 1st into a “day of Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer.”10 The hope was that by focusing on the difficulties that the people of Boston would soon face, they could show some opposition to the act, while not facing any backlash from the governor. The attempt, however, failed. The next day, summoning the Burgesses before him, Governor Dunmore with a copy of the resolution in hand, dissolved the House, saying that it reflected poorly on the King and Parliament.11 This dissolution outraged some of the Burgesses, with Landon Carter, a representative from Richmond County, having noted in his diary that the dissolving of the House for passing such a resolution was the first time that an act of that nature had ever been viewed as “derogatory” to either the King or Parliament.12

The dissolution of the House led the members of the late body to meet the next day, May 28th, at the Raleigh Tavern, to further discuss the current affairs. However, they failed to do much at this meeting. The members merely signed a limited non-importation agreement that would refuse the importation of East India Company goods, and even then, there were a couple of exceptions. They then asked the Committee of Correspondence to write to the other colonies to find out what their thoughts were about “the Appointment of Deputies from the several Colonies to meet annually in general Congress.”13 These measures, as Ammerman has observed, were overly moderate for the Burgesses.14

However, Virginia would take a firmer stance the next day when a letter from the Annapolis Committee of Correspondence came to Peyton Randolph. The letter included in it a forwarded copy of resolutions from Massachusetts and Maryland, as well as a letter from Philadelphia, which all led the remaining Burgesses to regain some of their zeal. In order to consider the matter, Randolph called a meeting of the remaining twenty-five Burgesses that had yet to leave Williamsburg. Unlike the day before, as Ammerman shows, the Burgesses moved towards passing more aggressive resolutions. Most supported a full non-importation agreement, while there was a split between whether or not to adopt a non-exportation agreement as well, with some saying that such a move could very well harm the Virginia economy. In the end, given the small number of representatives present, they decided not to do anything that would have serious implications for the whole colony. Instead they would return to their respective homes, gather the sentiments of their constituency, and return to Williamsburg on August 1st to convene in a provincial congress.15

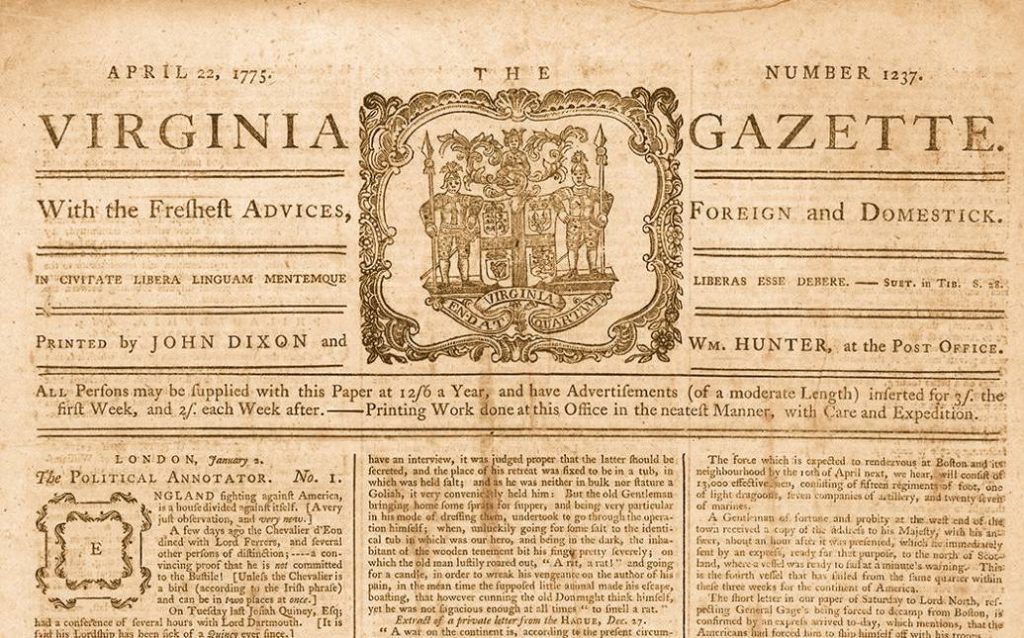

The Summer Resolve

When the former Burgesses returned to their home counties and towns in order to gather the thoughts and opinions of their constituents, local meetings were held for the “Freeholder and other Inhabitants” of the area. The voice of Virginians could be heard from these local county and town meetings that took place that summer. Between the representatives’ return home and their return to Williamsburg, Virginians across the colony came together to debate the issues and express their thoughts not only to their representatives, but also to their fellow British subjects in the colony. This can be seen by the fact that so many local resolutions dealing with the matters at hand were published in the Virginia Gazette. After having adopted resolutions pertaining to, what some referred to as, the “distressed and alarming Situation of Affairs throughout the British Colonies in America,” the people repeatedly requested that their resolves be sent to the printers in Williamsburg for publishing.16 Virginians everywhere felt the need to send their resolves out as a declaration of their thoughts and feelings, a statement of their stance on the present conditions of their home.

In an address to the inhabitants of York County, Thomas Nelson captured the sentiments of many of his fellow Virginians. He started off by declaring that the British Parliament had attacked something that was much more important to all of them, to all of British America, than their lives: their liberty.17 Gordon Wood has remarked that liberty for the English, including the colonists, was of enormous importance. Unlike so many other people in the world, the English “had their habeas, their trials by jury, their freedom of speech and conscience, and their right to trade and travel; they were free from arbitrary arrest and punishment; their homes were their castles.”18 To Nelson, and so many other Virginians, an attack on and deprivation of their liberties was a denial of their status as freeborn Englishmen, a status passed down to them from their ancestors to be passed from them to their posterity. As subjects of the King of Great Britain, they were entitled to all the “Rights, Liberties, and Privileges” that any of their fellow English subjects enjoyed in the mother country. These rights and liberties, as the Albemarle County resolves announced, came first from nature, and were later confirmed by constitution and charters. And while many Virginians still wished to continue their connection with Great Britain, to continue to be subjects of that empire, they declared over and over that they would, under any circumstances, defend their rights as free Englishmen in order to prevent themselves from being driven into a state of slavery.19

The possibility that Virginians could soon face such a deprivation of their rights and liberties that they would become slaves themselves is reiterated on numerous occasions during this time. While a powerful line of rhetoric, the meaning and history behind the prospect of the loss of liberty speaks volumes to the fears of Virginians. As Peter Dorsey has pointed out, living in such a major slave society, Virginians had a unique relationship with the concepts of freedom and tyranny.20 On one hand, Virginians grew up knowing and experiencing freedom and liberty as British subjects. Their liberty, as mentioned earlier, was seen to be the most robust in the world. Yet, on the other hand, they also witnessed the ultimate denial of freedom and liberty in slavery.

Slave owning planters were born as masters over other people. Slavery was their biggest fear, not only because it meant a loss of their rights, liberty, and freedom, but also because this close acquaintance with the practice brought home to them its horror. A letter from George Washington illustrates this point perfectly. While most people would simply state that the acts would force them into a state of slavery, and leave it at that, Washington went further, saying that they could be made “tame, & abject Slaves, as the Blacks we Rule over with such arbitrary Sway.”21 Washington’s addition to the common metaphor shows just how much he recognized the parallels between what Parliament was doing, and what slave owners, himself included, had been doing for over a century.

More realistically, Virginians feared that their right of consent would be revoked. In their resolutions, the citizens of Fairfax County stated that it was an indispensible part of the British constitution that the people of the empire were not to be governed by any law that they had not consented to themselves, or by the representatives that they had chosen to act on their part. They then went on to say that the subjects of British America were not, nor could they ever be, fairly represented by the British Parliament. This unfair representation came from the fact that the colonists had no influence in determining the elections to Parliament. Because of this, colonists believed that Parliament, on many occasions, had interests that were not only removed from that of their British American subjects, but at times completely opposite.22

Questions about representation and consent bring up the issues of taxes. The right of Parliamentary taxation had been in dispute for some time, beginning in force almost a decade earlier with the passage of the Stamp Act of 1765. Many colonists denied Parliaments right to tax the colonies, as virtual representation could never provide any real representation for the colonies. The inhabitants of Fairfax County would declare that “taxation and representation are in their nature inseparable.” The subjects in New Kent County joined in, saying that it was the right of the colonial assembly to levy taxes on the people of Virginia, where the people could truly be accurately and fairly represented. The colonists of Virginia thought that the provincial assembly had the only legitimate right to “impose Taxes or Duties” being that it was where “the legislative Authority of the Colony is vested.”23 In the minds of Virginians, it was only in the House of Burgesses, where members of local communities were elected, and not Parliament, that the people were actually represented.

From representation and taxes, many Virginians turned their attention to Boston in their resolves. In a letter, Edmund Pendleton of Caroline County expressed the view of many Virginians, saying that while he thought it was wrong that the Bostonians destroyed the tea, the actions of Parliament went far beyond wrong, and were simply dangerous. For Pendleton, by “giving Judgment and sending ships and troops to do Execution in a case of Private property,” Parliament had initiated an “Attack upon constitutional Rights.”24

The people of Dinwiddie County shared similar thoughts thinking that the acts passed by Parliament “deprive a whole People of their Rights for the Trespass committed by a few.”25

Blocking the port of Boston, especially with warships, was seen as proof of Parliament’s intention to deprive the British colonists of their rights and liberties. The citizens of Dunmore County said that the use of a “military power,” by Parliament, “will have a necessary tendency to raise a civil war.” And the people of Boston would surely suffer under horrible conditions after being forcibly cut off from trade, and, in effect, their livelihood. In addition, the dissolving of Massachusetts’s assembly was not only unconstitutional in the minds of Virginians, but a direct violation of that colony’s charter. And the Administration of Justice Act, often called the “Murder Bill,” startled many Virginians. This bill, in their eyes, would allow authorities the power to simply kill someone and get away with it.26

To so many Virginians, the acts passed by Parliament were not aimed solely towards Boston and the colony of Massachusetts. These acts were simply the opening salvos in what would eventually become an attack on all of British Americans’ rights and liberties. Given enough time, Parliament would pass legislation that mirrored that of the Intolerable Acts in each of the colonies. The most recent acts were nothing more than “a Prelude to destroy the liberties of America,” and should be seen “as a dangerous alarm.”27 In order to preserve their liberties, Virginians considered completely stopping commerce with Great Britain. By cutting off commerce, Virginia could, as Thomas Nelson put it, “make those who are endeavoring to oppress us feel the Effects of their… arbitrary Policy.”28

In general, Virginians were in agreement on non-importation from Great Britain, but there was some apprehension about stopping all exports. The former representatives of the House of Burgesses could not agree to a non-exportation plan before returning home because some feared that such a plan would only prove detrimental to Virginia’s economy. Others were not sure whether or not it was just to stop exports, considering the amount of debt that many Virginians still owed to English merchants. Thomas Nelson said something similar in his address, but stated that “no Virtue forbids” the stopping of importations. Eventually, however, most Virginians approved of a non-exportation plan. Virginians would have to put their hopes of amassing a fortune on hold for a time. But as Nelson put it to the inhabitants of York County, there was no point in having a fortune when it could simply be taken at any time.29

In their resolutions, Fairfax County stated that if the grievances of British America were not addressed by September 1st of 1775, they would not, as long as the other colonies followed the example, plant any tobacco. Many of the Virginia resolutions recommended stopping engagement in any kind of luxury, but instead engage in manufacturing and industry. The raising of sheep was particularly encouraged among people, and those who had large herds of sheep were also encouraged to sell some to their neighbors at a fair price, so that the production of wool in the colony would increase at a faster rate.30 A life of frugality and increased manufacturing was needed in the times ahead for Virginia. While cutting off commercial ties with Great Britain allowed Virginians and their fellow colonists to deal a blow to the mother country, it would subject them to many inconveniences and force them to rely on themselves for more and more things. However hard the struggles were, Virginians were prepared to take a hit in one part of their lives if it meant the preservation of something more important.

A Dialogue between Friends

Up to this point, this paper has dealt with what could be described as a patriotic response to the Intolerable Acts. While there was certainly an overwhelming call for support and unity against the British policy, it is only fair to take a moment to note that there was not complete unanimity among Virginians. Some would have been against the actions presented in these summer resolves, or at least, unsure which side to choose. This point is illustrated beautifully in a handful of letters exchanged between George Washington and one of his neighbors, and friend, Bryan Fairfax. George Washington, who had presided over the Fairfax County Committee during its summer meeting, was an advocate of the common cause of America, and of defending his fellow subjects in Boston. Bryan Fairfax, on the other hand, falls somewhere between the two camps of colonists. While not a disinterested bystander, Fairfax himself was unable to fully commit to either side. A sort of moderate, the correspondence between him and Washington gives insight into the multitude of opinions that would have been present in Virginia during this time.

The correspondence began July 3rd, shortly before the meeting of the Fairfax County Committee, with a letter from Fairfax to Washington. In the letter, Fairfax informs Washington, that while he would have liked to work with him, he had to decline the position because he knew that he would not fall in line with the majority, or as he put it, “I should think Myself bound to oppose violent Measures now.” Fairfax was referring to the plan to stop trade with Great Britain. While this was a fast growing sentiment among the people of Virginia, Fairfax could only support a non-threatening petition to Parliament, in which the legislative body would be given an opportunity to repeal the acts. While not a believer in the right of Parliamentary taxation, Fairfax also was not a believer that a non-importation agreement would even be adhered to by the general public.31

Washington’s response to this would be far from the moderate mindset that Fairfax held. Petition, in his mind, was nothing more than a waste of time, as it had been made in the past to no avail. And if the continued disregard for colonial petitions was not enough, the late acts of Parliament made it “as clear as the sun in its meridian brightness” that there was a plan to tax and deprive the American colonies of their rights and liberties. Not only had Parliament blocked the port of Boston with the British Navy, before any request for compensation was made, but the Administration of Justice Act effectively set a precedent for eliminated justice in the colonies. In Washington’s eyes, petitions could no longer serve a purpose. Economic threats, in the form of boycotts, were a viable defense against Parliament’s late, and potential, acts.32

However, for Washington, there was proof that the practices of Parliament were nothing more than the “most despotick System of Tyranny that ever was practiced in a free Government.” Their actions through laws, including their most recent ones, their debates while in session, and even the conduct of General Gage, the new military governor of Massachusetts, proved the existence of such a system. Their repeated attempts at taxing the American colonists were much too serious to simply address with a petition. They went against the very constitution of England and violated the laws of nature. For Washington, Parliament had as much a “Right to put their hands into my Pocket, without my consent, than I have to put my hands into yours.” And as far as Fairfax’s continuing concern about non-importation and exportation, and the participation in it, Washington could only have faith in his fellow Virginians that there was “publick Virtue enough left among us to deny ourselves every thing but the bare necessaries of Life.”34

Fairfax’s next letter reveals his opinions about many of the various parts of the controversy. Along with this, he also provides testimony about the thoughts of other like-minded men. He states that a Mr. Henderson thought that the Intolerable Acts could not have been avoided considering the conduct of the Bostonians. He also stated that Henderson thought that the Massachusetts Government Act was a suitable solution given the “factious Conduct of the people.” Fairfax himself thought Parliament had overreached in this act, saying that the constitution and charters should only ever be changed when the people have decided to change them, although he did add that a change in Massachusetts’s constitution could be good. As for the Boston Port Act, one can observe a marked difference from the overall attitudes of Virginians. Fairfax had only one qualm with the act, stating that he did not approve of the fact that the king could decide to keep the port closed even after the repayment of tea had occurred. He also stated that he thought that the tea should have been paid for in full before the other colonies pledged their support to Boston.35

This correspondence between these two men also gives insight into what it would have been like for men of “dissenting” opinion during this time in Virginia. Fairfax, in his letters, mentioned several times that he knew that his opinions were not shared by many of his counterparts. In his first letter he stated that there were barely any in Alexandria that shared his views. One can see throughout this short correspondence a sense of confusion from Fairfax, as he tried to reconcile his disagreement with that of the majority. In another letter, he went as far as to say that he had “Reason to doubt” his own thoughts, as “so many Men of superior Understanding think otherwise.” He went on to describe the opinions of some other men that shared his thoughts, so that Washington would not believe that his thoughts were “quite so singular as they appeared to be.”36

Besides himself, Fairfax gives testimony to the hardships that others had faced as a result of their controversial opinions. A Mr. Williamson confided in him that at a meeting at Fairfax County, there were some who felt that there was no point in speaking up against some of the resolves being brought up, and that they felt they could not speak their minds. At another meeting, this one in York, Fairfax explained to Washington that there were only two men who went against the will of the majority, and were therefore “very unpopular.”37 One can see, through Fairfax’s letters, how the minority dissenters were beginning to be shunned, in a sense, early on in the summer, a pattern that would continue to manifest throughout the year.

A New Train of Thought

By late summer Thomas Jefferson was working on what he hoped would become the instructions for the delegates to the general congress. Falling ill before he could deliver them himself, he sent two copies, one to Peyton Randolph, who would be the speaker of the meeting, and one to Patrick Henry. While not adopted by the convention, the document was printed in the Virginia Gazette and eventually in Philadelphia and London. Jefferson’s “A Summary View of the Rights of British America” can be seen as a somewhat more radical document than those produced before it during 1774. It certainly set forth a strong stance on the matters at hand, and was one of the first documents to make Jefferson known to the world.38

One of the most striking parts of Jefferson’s “A Summary View” was the assertion that Parliament had no right to rule the British American colonies. Disregarding any talk of fair representation in Parliament, Jefferson holds that the colonies were independent from Britain since their founding. In Jefferson’s mind, “Their [the initial immigrants to America] own blood was spilt in acquiring lands for their settlement, their own fortunes expended in making that settlement effectual; for themselves they fought, for themselves they conquered, and for themselves alone they have right to hold.”39 Jefferson is essentially asserting that from the day colonists stepped forth in the New World, acts of Parliament no longer applied to them. The original colonists, in his mind, simply adopted the same form of government, the British one, to which they had been accustomed. There were, however, no measures to force them to do this, nor to impede them from doing otherwise. For Jefferson, the fact that they had done this did not mean that Parliament’s reach extended to America. And as a result, no acts of Parliament were legally applicable in the colonies.

It is worth pointing out that while this is certainly one of the more striking sections of Jefferson’s “A Summary View,” it was not a wholly original thought by the time he had written it. It is true that this, along with other features of the document, would lead some Virginians to label it as radical, and was certainly a reason for it not being adopted by the convention. Scholars have been quick to point out, however, that they often fail to recognize that the sentiments expressed in it were increasingly taking shape throughout Virginia during this time. One can observe this movement in Thomas Mason, a Burgess from northern Virginia, who had given this very same argument, saying that the colonists “owe no obedience to the British parliament, two branches of it being only your fellow subject, and not your masters.” Writing under the pseudonym A British American, Mason published a series of letters in the Virginia Gazette from June to July. He would eventually shed the cover and announce his true identity in his last letter, something that was both uncommon, and as Robert Scribner has noted, was “not without courage.”40

Mason’s seventh letter is quite possibly the most gripping of the series. For a moderate man who advocated moderate measure, Mason drew a grim picture for colonists and rebuked any Parliamentary right to legislate for the colonies. He opened the letter with two simple questions, the answers to which had far reaching implications. So important were these questions to Mason that the answers the colonists gave would almost certainly “preserve or sink the greatest empire in the world, and extend happiness or misery to myriads of millions yet unborn.” The first question was whether or not colonists would submit and acknowledge Parliament’s perceived right to legislate for the colonies. The second was, if not, then how would they go about opposing such acts by Parliament.41

To the first question, Mason had strong words to whoever believed in Parliament’s right to legislate for America. Vehemently against this notion, he would, like many Virginians, employ the metaphor of slavery to depict the colonists’ subjugation to Parliament. The distinction, in Mason’s mind, between trade regulations and taxes was so small and insignificant that it was not worth debating. Trade regulations, created by Parliament to effectively run the empire, had been an accepted part of colonial life. Even after the initial disputes started over taxation and representation with the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765, colonists were silent about these regulations, often referred to as Navigation Acts. However, by this time, the notion that Parliament could not even pass these for the colonies was beginning to take root. As Mason observed, such acts could just as easily deprive a person of their rights and liberties.42

Mason also attacked what he considered to be “feeble” protesters of Parliament’s unjust power. Their descent into slavery could take place just as readily as for those who agree with Parliament in the first place. Virginia, as well as the rest of the colonies, should stand up to Parliament’s rule. For those who knew that they had rights, it was high time to do more than simply protest. A moderate at heart, Mason still didn’t believed that the colonists should “leave it to your growing posterity to enforce those rights” to which he knew they were entitled. Those without enough backbone should simply submit to slavery, apologize for their former missteps, and promise their undying loyalty to Parliament. As Mason remarked, though, these same people should be careful in their vain act of resistance against their “masters” that they ultimately “do not intend to persist in.” Mason stated in an earlier letter that he was against rushing into any hasty resolutions.43

For Mason, it was time for the colonies to unite and stand up to Parliament’s attempts to rule over them. The opportunity could not be passed by, as Mason stated that, “if America is not now ripe for asserting her just rights, she will be rotten before she is so.” Even more crucial than the present moment was the future. The generations of people that would come after them depended on the efforts that had to take place at that time. Painting a truly grim picture of the future of British America, Mason continued, saying that the shackles of slavery would be so commonplace for their posterity that they would not even attempt to free themselves. It was then left up to the current generation to not only protect and assert their own rights, but those of the future. As Mason asked, would “three millions of people surrender their liberties without a single struggle?”44 Surely, the colonists would recognize the dire situation that was developing, and come to terms with the resistance that they had to put up.

Another notable part of Jefferson’s “A Summary View” was the discussion of the King’s power of veto. Jefferson went beyond merely discussing the veto, and went on to criticize the king for his use of it, or lack thereof; something that had not been done up to this point. Quite the opposite, in the county and town resolves, Virginians clearly praised their King, and pointed all of their frustrations at Parliament instead. Many of the county and town resolutions adopted during the summer included a confirmation of their continued loyalty to the king, and affirming his right to rule. Even Mason, who suggested such a grim future for America, was a staunch supporter of the king. Mason’s problem was the British Parliament and aristocracy. This, as Robert Scribner noted, was simply seen as “amiable and supposedly helpless” to Mason, a sentiment shared by many of his contemporaries.45 While Jefferson’s A Summary View is far from renouncing what the local resolutions had said, it does go further by putting some of the blame on the king for the current state of British America.

Recalling that the king had the power to veto any law passed by Parliament, Jefferson called on him to use his power in order to defend the interests of his American colonies. Instead of doing this, however, he vetoed laws passed by American legislatures for, according to Jefferson, little or no reason. Jefferson then goes on to state that the king continually disregarded colonial laws in Great Britain. The king, “neither confirming them by assent, nor annulling them by his negative,” simply kept them there. By doing this, the colonists were potentially at risk of his passing a law long after it was initially proposed, thus potentially harming the colonists, whose situations may have changed. And at the same time, the king had set limits on his colonial governors and assemblies, forcing them to include a suspension clause in new laws. Because of this they could not pass a law, no matter how urgent, until “it has twice crossed the atlantic, by which time the evil may have spent its whole force.”46

Jefferson’s “A Summary View,” along with its popularity, can be seen as the start of more radical thoughts emerging in the minds of Virginians, and their fellow British American subjects. Besides attacking the Intolerable Acts, and talking of the plight of Boston and Massachusetts, Jefferson challenged the colonists’ place in the empire. He attempted to paint a new history for the colonies, and give them new meaning with regard to their mother country. While not a pamphlet calling for independence, “A Summary View” can be seen as one of the first steps towards further challenges to Parliamentary powers, and eventually monarchal rule. Along with this, the popularity of Jefferson’s pamphlet transformed the voice of a Virginian into a statement from all of British America.

From Provincial Convention to the Rule of Committees

The local resolutions that came into being during the summer of 1774 time served as instructions for the delegates that would serve as representatives in the convention in Williamsburg on August 1st, 1774. At the meeting, the delegates did much the same thing that the people of their colony had done in the months preceding. They debated the issues, and came to decisions that would represent the opinions and interests of their constituents. The resolutions that they came to very much mirrored those that were produced in many counties in Virginia over the past summer. However, as the members of the meeting said, they were now presenting their grievances “unanimously, and with one Voice.”47

The resolves adopted by the representatives at the convention started by endorsing a firm non-importation agreement. With the exception of medicine, Virginia would no longer import any British good after November 1st. The representatives also made clear that tea would never be imported or used again by any of them. And the Burgesses, who in May originally aimed a weak non-importation plan at the East India Company, were months later taking a much stronger stance against the company. Believing that their fellow subjects in Boston had been and were being, “extorted” by the company for destroying the tea, the Virginia representatives announced that they would not import any commodity from the company until the inhabitants of Boston had been refunded the money that was wrongly taken from them. The other main point that can be taken from the resolutions was that a non-exportation agreement came into existence. Trying to find a way of justly stopping exportation, the representatives said that they would stop exporting all goods to Great Britain on Augusts 10th of 1775 if American grievances had not been addressed. This would allow people in Virginia, who still owed debts to British merchants, to make good on payments that they had already promised to pay. For many Virginians, a non-exportation agreement was both a moral grey area and an economic blow. Not knowing the events that would take place that year, they already had planted a crop and wanted to ship it. By waiting until the next year, Virginians were able to deal with both areas of trouble that arose from a non-exportation agreement, more so than if one had been implemented immediately.48

Along with the resolutions, the assembly of representatives also created a list of instructions for the delegates that would meet at the general Congress in Philadelphia. However, the delegates did not need these instructions. As Robert Scribner notes, the instructions were “pointed propaganda” to be printed in the Virginia Gazette.49 All of them had participated in their own local county and town meetings before coming to the provincial meeting, and knew full well what their fellow Virginians wanted.

Moving forward to September 5th, fifty-six delegates met in Philadelphia for what would be called the First Continental Congress. All the colonies were present, with the exception of Georgia, which chose not to send delegates because it needed help from Great Britain pacifying Native Americans on its border. The Congress would work from September 5th to October 26th, and pass several important resolutions that had implications that affected Virginia and the rest of the colonies. Virginia played a pivotal role in the Congress, teaming up with Massachusetts to beat the more moderate colonies as much as possible.50

Samuel Adams along with his cousin John Adams came to the Congress already with a reputation for being radical Bostonians. During their travels to the Congress, they had learned that Virginia seemed to be just as radical as their own colony, and could prove to be a friend to Massachusetts. The delegates from Massachusetts, finding that Virginia would be willing to put up a strong fight against Great Britain, even if war occurred, befriended the delegates. Commonly referred to as the “Adams-Lee junto,” named after Samuel Adams and Richard Henry Lee, the two colonies fought together to get important measures passed. Knowing that they would be ignored more than Virginia for being perceived as more radical, the Massachusetts delegation had the Virginia delegation propose measures that they, more or less, thought of. Massachusetts was a strong force in New England and Virginia was the most powerful of the Southern colonies. Being that both had large populations and influence, an alliance between the two was a tremendous help to both. As John Ferling has observed, the “Adams-Lee junto” worked effectively. Not only were the two colonies able to get measures that they supported passed, but it also tricked many of the delegates into believing that Massachusetts was more moderate than previously thought. By the end of the Congress, Virginia over Massachusetts was believed by many delegates to be the more radical of the two colonies.51

There were two major decisions that the First Continental Congress made during the time it met. The first was to adopt a nonimportation plan that was proposed by Virginia for all the colonies. There was a division among the delegates, between those who wanted and those who did not want a boycott. However, as Ferling observes, the first North vs. South division can be seen among those who favored a boycott. Massachusetts came to the Congress seeking a complete ban that included both imports and exports. Virginia and other southern colonies on the other hand favored the immediate start of a non-importation plan, but wanted to wait till the next year to begin a non-exportation plan. Since their crops were already planted, enacting a non-exportation plan immediately would mean that they would lose their market. By waiting until 1775, Virginians, as well as the other southern colonies, would have much more time to prepare. Eventually, Massachusetts and the other northern colonies that favored a boycott gave in to southern demand, a pattern that Ferling stated would become commonplace in years to come.52

The second major decision by the Congress relates to the first, as when it adopted the non-importation plan, or the Continental Association, it placed enforcement of the Association in the hands of individual committees in the various counties, towns, and cities that made up the colonies. These committees were important not only because they helped enormously towards the success of the Association, cutting British imports by about three times, but also because their formation resulted in the election of thousands of people to public office. This decision provided many Virginians with a chance to hold their first public office. The increased chance for political participation did not go unnoticed in Virginia. As Ammerman has shown, surviving records indicate that at least 51 of Virginia’s 61 counties formed elected committees. It is most likely, however, that all of the counties formed such committees, as “the Association called for condemnation of counties which failed to do so, and there are no records of such condemnations.”53

These local committees took the charge of enforcing the Association very seriously. Many of the committees in Virginia circulated loyalty oaths among the people of their respective counties and towns, having them sign that they would uphold the terms of the Association. Those found to have gone against the agreement were often publicly ridiculed in the Virginia Gazette. However, the committees did not limit themselves to simply calling out a person who didn’t follow the Association. Those who spoke out against the “dearest rights and just liberties of America” found themselves feeling the wrath of these local committees as well. Malcolm Hart had to publicly apologize to the Hanover County Committee after it became known that he had said, “a little Gold, properly distributed, would soon induce the People to espouse the Cause of the Enemies of this Country.”54

An example of local committees taking it upon themselves to persecute those who spoke out against the American cause can be seen in David Wardrobe, a teacher in Westmoreland County. A letter that he wrote to Archibald Proven came into public scrutiny after it was printed in the Glasgow Journal. Charged with misrepresenting the affairs of Virginia, and deceiving the people of Great Britain, Wardrobe was summoned before the committee to stand judgement. However, before this could happen, the county in a set of resolves published in the Virginia Gazette called for Wardrobe to no longer be allowed to use the Cople Parish where he taught, and that all parents should take their children out of his school. After failing to come before the committee, and writing a letter “rather insulting, than exculpatory” for why he wasn’t there, he was publicly ridiculed for a second time, before finally apologizing publicly.55

The York County Tea Party

The culmination of Virginians’ response to the Intolerable Acts of 1774 occurred in November of that year in York County, showing that they were “very warm in the American cause.” On Monday the 7th, the ship Virginia came into harbor. It quickly became known by the inhabitants of York and Gloucester County that the ship contained two chests of tea. Twenty-three members of the Gloucester committee, along with an unspecified number of other citizens, assembled to discuss the proper course of action for dealing with the tea. Upon hearing that members of the House of Burgesses had begun deliberating on that same matter that morning, the people of Gloucester decided to wait until they heard the Burgesses’ answer. However, after waiting until after twelve o’clock, the members of the community decided to simply go to the ship so that they could meet with members of the York County Committee and discuss the problem with them.56

What had occurred during this time was an outstanding testament to Virginians’ commitment to the common cause of America. It spoke more than any set of resolutions or instructions ever could. When the members of the Gloucester community arrived, they “found the Tea had met with its deserved Fate, for it had been committed to the Waves.” According to an account of the situation, published by the York County Committee in the Virginia Gazette, the people of York County had gathered at the ship at ten o’clock, and waited much like the people of Gloucester County for word from the House of Burgesses. However, after a messenger they sent to the House to inquire on the proper actions to take came back empty handed, the members of the York County community took matters into their own hands.57

According to the “official” report of what happened, this act of protest mirrored that of the Boston Tea Party. The York County Tea Party was a nonviolent act of protest, in which the people simply “hoisted the Tea out of the Hold and threw it into the River, and then returned to the Shore without doing Damage to the Ship or any other Part of her Cargo.” However, it should be noted that a later account would completely go against this image of a nonviolent tea party. A short extract, only eight lines, from a Virginian letter, informed readers of what had occurred at York County that day. Printed in several colonial newspapers in other colonies, at one point it stated, “it was with great difficulty that the ship was saved from being burnt.” Whether this account is true is impossible to know at this point, especially since it is never stated who wrote the letter. However, the short extract was never printed in the Virginia Gazette, which could signify that Virginians were attempting to paint a slightly more orderly image of that day.58

In either case, after coming to the ship only to see that the tea had already been disposed of, members of the Gloucester County Committee left and adopted a number of resolutions dealing with the situation. The Committee attacked John Norton, the British merchant who had sent the tea, saying that he “has lent his little Aid to the Ministry for enslaving America, and been guilty of a daring Insult upon the People of this Colony.” The York County Committee chimed in days later in a set of resolutions it adopted, saying that Norton would have known of “the Determination of this Colony with Respect to Tea” when he shipped it.59

Both the Gloucester and York County Committees also attacked the captain of the Virginia, Howard Esten, with Gloucester saying that “he has drawn on himself the Displeasure of the People of this County,” and York saying that he should have refused to carry the tea to Virginia in the first place. Esten, who had apparently been working in his trade for some twenty years, had, up to this point, been in good favor with the people of Virginia. However, even given this, his actions, and “departure from virtue and duty,” could not be overlooked. The people of Gloucester even went as far as to announce that they would not, from that point on, ship any of their tobacco on the Virginia, and recommended that the other counties of the colony follow suit.60

A third person, however, felt the wrath of the people of these two counties more than John Norton or Howard Esten ever would. The merchant John Prentis, for whom the tea was shipped to, faced public ridicule in both the of the counties’ resolutions. Gloucester County announced that Prentis had “justly incurred the Censure of this County, and that he ought to be made a publick Example of,” with York County approving, saying he should “be made to feel the Resentment of the Publick.” There is no doubt that many Virginians across the colony knew the name John Prentis by the end of the month, as both of the counties’ resolutions were printed in the Virginia Gazette on the 24th. In the same issue, a public declaration by Prentis in response to the problem was printed. Apologizing for the situation, Prentis stated that he did not mean to have “incurred the Displeasure…of the Publick in general, for my Omission in not countermanding the Order…for two Half Chests of Tea.”61

Prentis’s public apology was seemingly only a half-hearted attempt to get back on good terms with his fellow countrymen. As a merchant, the public pressure and scrutiny that he faced most certainly affected his business. The one paragraph apology was most likely a way to make up for being caught. However, the experience did leave its mark on Prentis. On December 7th, less than two weeks after his public apology, he made sure to inform the James City County Committee that he had a shipment of cutlery that had arrived on a ship from Glasgow, which he had ordered the summer before. He told the committee that it was still “unopened, on Board of the Ship, at the Ferry, and submitted to the Committee to dispose of it as they thought proper.”62 Prentis certainly felt the backlash from his last mistake with the tea, and wanted to ensure that he did not cause yet another public outcry damaging to his reputation.

While not the three hundred chests of tea that characterized the Boston Tea Party, the York County Tea Party deserves to be seen in the same light as its Massachusetts antecedent. The Virginia version may have been on a smaller scale, but it still warrants a place in history. This event, like no other, sums up the sentiments of Virginians when it came to the Intolerable Acts.

At Year’s End

The year was coming to a close, and throughout it, Virginians had made clear their position on the affairs that now faced them and the rest of British America. The summer of 1774 was characterized by numerous county and town meetings, where the people of the colony came together to express their sentiments in declarations “intended to manifest to the World the Principles by which they are actuated in a Dispute so important” that it would shape the “political Existance of all America.”63 From this, Virginians sent their representatives to the colonial capital, where they presented a united front to the other colonies and Great Britain. In Philadelphia, the Virginia delegation helped to shape the affairs of not just their own colony, but that of all of British America. By the year’s end, Virginians had continued to show the zeal that they were known for.

Throughout 1774, Virginians had made it known that they were not willing to accept any deprivation of their rights and liberties. Just like their fellow American colonists, they were subjects of the British Empire after all, freeborn Englishmen under the protection of the English constitution. While separated not only by physical distance, but also in ideals, politics, and social customs, Virginia and her sister colonies had many differences. For many years they were linked together only by their common parentage. However, as time went by, and policy after policy from Great Britain continued to irritate and anger the colonists, these separate colonies began to come together. And during 1774, Virginia played an important part in this, seeing that “the closest union among Ourselves, and the firmest confidence in each other, are our only Security for those Rights, which as Men and Freemen, we derive from Nature and the Constitution.”64

When Virginians looked to Massachusetts and the town of Boston, they saw something that invoked fear. In their eyes, the Intolerable Acts were a mechanism that would soon be used in all the colonies; Boston was simply the beginning. Historian Eric Burns, in his book about the beginnings of American journalism, summed up the view of the Intolerable Acts nicely when he stated that they were “not policy but punishment, not rule but retribution.”65 These acts marked the beginnings of a new kind of tyrannical rule from across the ocean. In these acts, Virginians saw more than their brethren being oppressed by arbitrary power that originated thousands of miles away. In the suffering of Bostonians, they saw their own future suffering. As they watched the liberties of those people continue to be stripped away, they felt their own liberties being taken. Boston was not alone in British America, and its people were not only suffering for themselves. As the people of Norfolk and Portsmouth put it to the Boston Town Committee, they would not be “indifferent spectators” to their plight.66

In Boston, Virginians saw what could become of the rest of British America. Boston’s cause “is and ever will be considered the cause of America.” After trying on so many occasions to find redress for their grievances in the past, Virginians were tired of simply sending a dutiful and submissive message to their mother country. In 1774, Virginians, along with the rest of their fellow subjects, started to test their own strength, and began using more assertive measures to make it clear that they would not back down. Instead of simply sending a list of resolutions with a humble plea, they stood up and tried another tactic. While boycotts had been attempted in the past, the boycotts of 1774 would prove to be the most successfully executed yet. Moreover, as Virginians showed, the year would strengthen colonial unity and resolve, both at the individual colony level, and on the broader scale of British America. Virginians’ resolve, from their meetings, to their resolutions, to their tea party, testified to their commitment to the ever-strengthening common cause of America.

Appendix

Notes

1Benjamin L. Carp, Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party & The Making of America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 20-21; John Ferling, A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 106.

2Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 192-193.

3Ferling, A Leap in the Dark, 107; Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 193-194.

4Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 194.

5Carp, Defiance of the Patriots, 194.

6David Ammerman. In the Common Cause, American Response to the Coercive Acts of 1774 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1975), 10-11.

7Ammerman, Common Cause, 28; John Cruger to Peyton Randolph Esqr., March 1, 1774, in Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, Vol. II, ed. Robert Scribner (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1975), 64.

8Delaware Committee to Virginia Committee, May 26, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 82; Charles Thomson to Peyton Randolph Esqr., June 20, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 122.

9Ammerman, Common Cause, 30.

10Jack Greene, ed., The Diary of Colonel Landon Carter of Sabine Hall, 1752-1778, V. 2 (Richmond: William Byrd Press, 1987), 818.

11Kennedy, John Pendleton, ed., Journal of the Virginia House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1773–1776, Including the records of the Committee of Correspondence (Richmond, Virginia: Virginia State Library, 1905), 13.

12Green, Landon Carter, 818.

13Proceedings, May 28, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 84.

14Ammerman, Common Cause, 31-32.

15Ammerman, Common Cause, 32-33.

16York County, July 18, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, Vol. I, ed. Robert Scribner (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1975), 165.

17York County, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 165.

18Gordon Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1992), 13.

20Peter A. Dorsey, Common Bondage: Slavery as Metaphor in Revolutionary America (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2009), 23.

21George Washington to Bryan Fairfax, July 4, 1774, in George Washington, Writings, ed. John Rhodehamel (New York: Literary Classics of America, 1997), 158.

22Fairfax County, July 18, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 127-129.

23Fairfax County, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 129; New Kent, Revolutionary Virginia, 1:147

24Edmund Pendleton to Joseph Chew, June 20, 1774, in The Letters and Papers of Edmund Pendleton, 1734–1803, Vol. I, ed. David Mays (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1967), 93.

25Dinwiddie County, July 15, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 121.

26Dunmore County, June 16, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 123; Caroline County, July 14, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 115; York County, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 167.

27Greene, ed., Landon Carter, 2: 818.

28York County, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 166.

29York County, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 166.

30Fairfax County, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 130-132.

31Bryan Fairfax to George Washington, July 3, 1774, in Letters to Washington and Accompanying Papers, Vol. V, ed. Stanislaus Murry Hamilton (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1902), 19-21.

32George Washington to George William Fairfax, June 4, 1774, Washington, Writings, ed. Rhodehamel, 152-153. 33Bryan Fairfax to George Washington, July 17, 1774, Letters to Washington, ed. Hamilton, 23-29.

34George Washington to George William Fairfax, June 20, 1774, Washington, Writings, ed. Rhodehamel, 154-156.

35Bryan Fairfax to George Washington, August 5, 1774, Letters to Washington, ed. Hamilton, 35-36.

36Bryan Fairfax to George Washington, July 3, 1774, Letters to Washington, ed. Hamilton, 21; Bryan Fairfax to George Washington, August 5, 1774, Letters to Washington, ed. Hamilton, 33.

37Bryan Fairfax to George Washington, August 5, 1774, Letters to Washington, ed. Hamilton, 34-35, 37.

38Editor’s Note, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 240-242.

39Thomas Jefferson, “A Summary View of the Rights of British America,” August 8, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 243-244.

40Thomas Mason, “The British American, No. IV,” Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 171-172; Editor’s Note, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 169-170.

41Mason, “The British American, No. VII,” Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 182-183.

42Mason, “The British American, No. VII,” Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 183.

43Mason, “The British American, No. VII,” Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 183-184; Mason, “The British American, No IV”, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 171.

44Mason, “The British American, No. VII,” Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 184-185.

45Jefferson, “Summary View,” Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 145; Editor’s Note, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 169.

46Jefferson, “Summary View,” Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 256. 47Convention Association, August 1, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 232.

48Convention Association, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 232-233.

49Editor’s Note, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 236

50Ferling, A Leap in the Dark, 112-114.

51Ferling, A Leap in the Dark, 114.

52Ferling, A Leap in the Dark, 116.

53Ferling, A Leap in the Dark, 121; Ammerman, Common Cause, 106, 106n.

54Resolutions Condemning David Wardrobe, November 8, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 165; Hearty Sorrow of Malcolm Hart, December 1, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 180.

55Scribner, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 136n; Recantation of David Wardrobe, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 179-180.

56New-York Journal, December 8, 1774, 2; A Daring Insult upon the People of This Colony, November 7, 1774 Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 163.

57A Daring Insult, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 163; Narrative of the Yorktown Tea Party, November 7, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 164.

58Narrative of the Yorktown Tea Party, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 164; Boston Evening Post, December 12, 1774, 2; Pennsylvania Packet, December 3, 1774, 3; Pennsylvania Gazette, November 30, 1774, 3.

59A Daring Insult, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 163; Condemnation of Tea Merchants and Ship Captain, November 9, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 166.

60A Daring Insult, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 163; Condemnation of Tea Merchants and Ship Captain, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 166; New-York Journal, December 8, 1774, 2.

61A Daring Insult, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 163; Condemnation, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 166; Publick Declaration of Mr. John Prentis, November 24, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 175.

62Cutlery, Thread, and Herring, December 7, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 184.

63Dinwiddie County, Revolutionary Virginia, 1: 120.

64Joint Committee to the Inhabitants of Charleston, S.C., May 31, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 94.

65Eric Burns, Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism (New York: PublicAffairs, 2006), 123.

66Joint Committee to Boston Town Committee, June 3, 1774, Revolutionary Virginia, 2: 112.

Works Cited

- Ammerman, David. In the Common Cause, American Response to the Coercive Acts of 1774. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1975.

- Carp, Benjamin L. Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party & The Making of America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Boston Evening Post, December 12, 1774.

- Burns, Eric. Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism. New York: PublicAffairs, 2006.

- Dorsey, Peter A. Common Bondage: Slavery as Metaphor in Revolutionary America. Knoxville: The Uni versity of Tennessee Press, 2009.

- Ferling, John. A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Greene, Jack, ed. The Diary of Colonel Landon Carter of Sabine Hall, 1752–1778, Vol. II. Richmond: William Byrd Press, 1987.

- Hamilton, Stanislaus Murry, ed. Letters to Washington and Accompanying Papers. Vol. V. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1902.

- Kennedy, John Pendleton, ed. Journal of the Virginia House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1773–1776, Including the records of the Committee of Correspondence. Richmond, Virginia: Virginia State Library, 1905.

- Mays, David, ed. The Letters and Papers of Edmund Pendleton, 1734–1803, Vol. I. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1967.

- New York Journal, December 8, 1774.

- Pennsylvania Gazette, November 30, 1774.

- Pennsylvania Packet, December 3, 1774.

- Rhodehamel, John, ed. George Washington, Writings. New York: Literary Classics of America, 1997.

Originally published by Philologia 7:1 (04.01.2015) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.