Talos stands as a compelling ancient precursor to artificial intelligence.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Throughout the ancient world, myths often served not only to entertain but also to convey deep reflections on the relationship between humans, nature, and technology. Among the more fascinating of these myths is the story of Talos, a giant bronze automaton of Crete. Created by the god Hephaestus, Talos was charged with protecting Europa and patrolling the island of Crete. At first glance, Talos appears to be a mythical guardian imbued with divine origin. However, a closer analysis suggests that Talos can be viewed as an early conception of what modernity now classifies as artificial intelligence (AI). This essay explores Talos as a mythological precursor to AI, examining how his characteristics parallel contemporary definitions of intelligent machines, and how ancient anxieties about artificial life echo today’s ethical debates surrounding AI.

Talos in Mythological Context

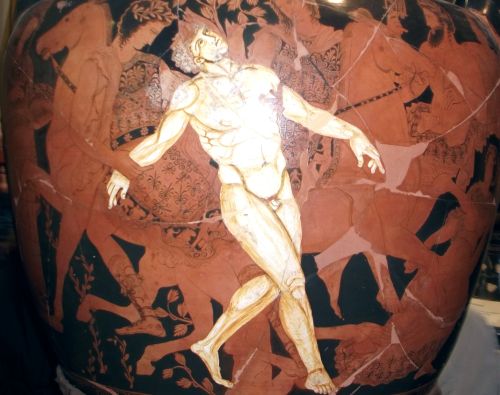

Talos occupies a distinctive place in the pantheon of Greek mythology as one of the earliest representations of artificial life, merging the mythic with the mechanical. According to the most widely known version of the myth, Talos was a giant automaton made entirely of bronze, constructed by the god Hephaestus and gifted to King Minos of Crete to serve as the island’s protector.1 He was not born of mortal parents nor fashioned from organic matter, setting him apart from traditional monsters or demi-gods. Rather, his composition of metal and animation through ichor—a divine fluid thought to flow in the veins of the gods—rendered him both supernatural and artificial.2 In mythology, Talos patrolled the coastlines of Crete, circling the island three times daily to repel invaders. His vigilant guardianship, accompanied by hurling massive stones at ships and heating his body to incinerate foes, portrays him as a programmed sentinel with limited autonomy. This function assigns Talos a liminal role between man, god, and machine, making him a unique figure in ancient mythology that illustrates early conceptions of mechanized agency.

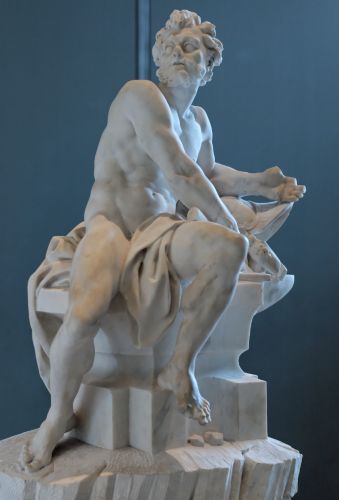

The creation of Talos by Hephaestus is significant within the broader mythological landscape of Greek antiquity. Hephaestus was the divine blacksmith and god of craftsmanship, often associated with the fusion of artistry and technology. His mythic workshop, populated by self-moving tripods and golden mechanical assistants, hints at an ancient fascination with automata.3 Talos is a logical extension of this mythological motif—an artifact endowed with purpose and movement, yet lacking the free will of mortals or immortals. This creative act by a divine artisan suggests a deliberate meditation on the limits of human and divine craftsmanship. It also indicates that the Greeks imagined the potential to manufacture life-like entities capable of performing roles typically reserved for sentient beings. Hephaestus’s role as Talos’s creator elevates the automaton from mere monster to a reflection of divine innovation, akin to the mythic progenitors of AI in modern science fiction.

Talos also fits into a broader mythical tradition in which artificial or constructed beings challenge or blur natural boundaries. Similar to Pandora, who was formed from clay and endowed with attributes by the gods, or Pygmalion’s Galatea, who was sculpted and brought to life, Talos exemplifies the recurring theme of artificial creation.4 These myths interrogate the human (or divine) desire to replicate life and explore the consequences of overstepping natural limits. Talos, in particular, brings this theme into the realm of militaristic and protective functions, suggesting that ancient cultures may have imagined mechanical entities primarily in the service of order, defense, and power. Unlike other artificial beings, however, Talos is not fully anthropomorphic in character; he speaks rarely if at all and operates more like a reactive system than a person with emotional depth or moral reasoning. This positions him within a mythic framework as a type of semi-conscious tool or weapon—evoking modern parallels to surveillance drones or robotic soldiers.

The myth of Talos reflects Cretan cultural identity and geography, as well as broader Greek attitudes toward technology and control. Crete, an island long steeped in mystery and mythological importance—from the Labyrinth of the Minotaur to the birth of Zeus—serves as a fitting setting for such a fantastical protector. Talos, in defending Crete from outsiders, also symbolizes a kind of mythic nationalism, embodying the island’s independence and self-sufficiency.5 His continuous movement around the island echoes the desire for absolute surveillance and control over territorial borders. The use of bronze as his material, a metal central to ancient technological development, further roots the story in an era of metalworking and mechanical experimentation. Talos can thus be seen as both a mythical construct and a symbol of Greek technological imagination—an embodiment of the dream that craft and invention might achieve godlike agency. The destruction of Talos at the hands of Medea in The Argonautica provides essential insight into ancient Greek perceptions of vulnerability in artificial constructs. Medea, a sorceress skilled in deception and manipulation, does not overpower Talos with force but instead exploits his one weakness—a plug in his ankle that seals his lifeblood of ichor.6 This narrative twist reveals an enduring mythological theme: the idea that every powerful creation has a fatal flaw, often hidden but exploitable. It also speaks to ancient concerns about the hubris involved in constructing artificial life or overreaching technological capability. Just as Talos is brought down by an external agent who understands his inner workings, so too do modern tales of AI catastrophe often hinge on human oversight or manipulation. In this way, Talos serves not only as a guardian of myth but also as a cautionary figure—illustrating the dual-edged sword of artificial power and the perils of mechanical perfection.

Talos as Artificial Intelligence

Talos stands as a striking ancient prefiguration of artificial intelligence. Though described in mythological terms, his characteristics—mechanical form, preprogrammed behavior, and functional autonomy—align closely with contemporary concepts of AI. Talos’s construction by Hephaestus, the god of metalwork and technology, provides a divine parallel to modern engineers and computer scientists who design intelligent machines. He was neither born nor biologically animated but was instead endowed with life by technological means—an artificial body animated by ichor, the divine analog of a power source.7 The fact that Talos could patrol the island of Crete and react to external stimuli without human direction suggests that he was equipped with a rudimentary form of artificial cognition, or at the very least, an autonomous operating system akin to algorithmic programming. Such a portrayal suggests that the ancients imagined machines not only as tools but as independently functioning entities.

The description of Talos’s behavior as guardian and enforcer implies an operational algorithm: he patrolled Crete in a regular pattern, recognized and responded to intrusions, and deployed violence to protect the island’s inhabitants. In this, he functions like a modern autonomous security system—what scholars might today term a lethal autonomous weapons system (LAWS). His limited but effective decision-making process recalls the logic-based behavior trees used in robotics and AI today.8 Talos’s responses are reactive rather than contemplative, driven by external conditions rather than internal thought processes. This parallels many current AI systems, which are designed to recognize specific inputs and execute pre-coded outputs. In Talos’s case, recognition of an intruder prompts him to hurl stones or immolate the threat with his heated bronze body. The myth thus provides an early conceptualization of the “if-this-then-that” logic that underpins machine learning and AI behavior.

While Talos lacks the self-awareness or adaptive learning of advanced AI, his autonomy challenges the boundaries between machine and life—a boundary that remains contested in modern discourse. The ancients did not conceive of intelligence in the same way as modern cognitive science, yet Talos’s function as an automated entity with a task-specific intelligence places him firmly within the early lineage of AI imagination.9 Like contemporary AI, Talos was built to serve specific human ends—security, order, and control—and his value was determined by his ability to execute these ends flawlessly. He is not a companion, nor a slave in the traditional mythological sense, but a tool with embedded agency. In this way, Talos anticipates present-day concerns about machine agency and moral responsibility. Can a machine that performs destructive tasks be held accountable, or is responsibility reserved for the creator? This same question is echoed in AI ethics debates today, particularly around issues of autonomous drones and algorithmic bias in decision-making systems.

The myth underscores a latent anxiety about the unpredictability and vulnerability of artificial beings. Talos’s destruction by Medea, who deceives him into removing the bronze plug that contains his ichor, illustrates a critical insight: even the most advanced artificial construct may have a single point of catastrophic failure.10 This recalls modern discussions of cybersecurity and the potential for AI systems to be hacked or misled by malicious inputs. Just as Medea exploits Talos’s programming to bring about his collapse, today’s adversarial attacks on AI—where input data is subtly manipulated to fool machine perception—reveal the fragility and potential danger of intelligent systems. Talos’s mythic vulnerability becomes a timeless metaphor for the risks associated with imbuing machines with power but not discernment. Talos serves as a symbolic predecessor to the moral dilemmas posed by artificial intelligence. His unquestioning obedience, lack of ethical reasoning, and overwhelming destructive potential align him with the archetype of the “obedient machine” who executes without contemplation. In contrast to figures like Daedalus, whose intelligence is marked by ingenuity and adaptability, Talos represents intelligence as blind function.11 This challenges the notion of whether intelligence requires consciousness or empathy, a distinction still debated in AI philosophy. The ancients may not have had access to the computational models we use today, but in Talos they articulated many of the same themes that animate our most advanced discussions of robotics and machine learning. He is both tool and agent, marvel and menace—an enduring symbol of the potential and peril of artificial creation.

Mythological Automata and Proto-Robotics

Talos represents perhaps the most famous and fully realized automaton in Greek mythology, but he is by no means unique in the mythological landscape of mechanical life. The ancient Greeks, particularly through the works of Homer and Hesiod, frequently engaged with the idea of self-moving devices and artificial beings created by gods or master craftsmen. Talos is part of a broader category of mythological automata—mechanical entities imbued with motion, purpose, and function without direct human control.12 Created by Hephaestus, the divine blacksmith, Talos joins a pantheon of animated machines that includes golden tripods that walked by themselves and mechanical handmaidens who assisted in the divine forge.13 These myths indicate that the ancients were not only aware of mechanical principles but also deeply fascinated by the idea that such principles could emulate life. They envisioned a world where technology, even in mythic form, could supplement or replace human labor and extend divine authority.

The concept of self-operating machines appears most vividly in Homer’s Iliad, where Hephaestus is described as crafting golden maidens endowed with intelligence, voice, and strength. These artificial assistants are not simply lifeless statues; they exhibit qualities closely associated with human capacities, such as awareness and dexterity.14 This vision of mobile, responsive helpers suggests an ancient awareness of the power inherent in automation. Although these figures were mythological, their detailed depiction implies that ancient audiences were capable of imagining the function and even the moral dimensions of artificial beings. In this context, Talos is the apotheosis of proto-robotics—a construct that blends strength, autonomy, and singular purpose. Unlike the golden maidens, Talos is also militarized, showing that mythological automata could extend beyond domestic or workshop settings and into strategic and combative roles.

Ancient proto-robotics, as evidenced by figures like Talos, reflects the early integration of technological imagination with religious and philosophical concerns. Myths involving automata were not merely entertaining or speculative stories; they often served as meditations on the boundaries between the animate and inanimate, the mortal and divine. For instance, Daedalus—the legendary inventor often considered a mortal counterpart to Hephaestus—is said to have created statues so lifelike that they had to be chained down to prevent them from moving away.15 In such stories, the artificial is treated as nearly indistinguishable from the natural. This blurring of categories anticipated later philosophical debates about the essence of life and consciousness, themes central to both the mythology of Talos and modern discussions of AI and robotics. In these narratives, the ancients were not simply toying with the idea of machines—they were philosophizing about what it meant to create life.

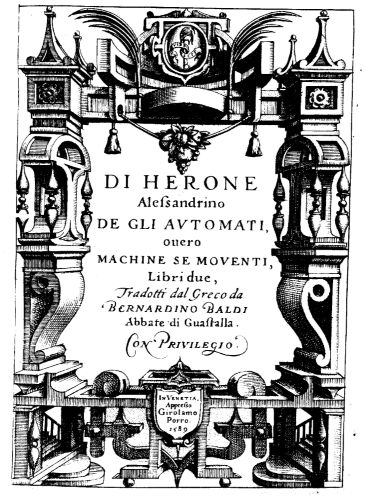

Technologically, the myth of Talos may have found inspiration in early Hellenistic engineering feats. Although myth precedes history, the mechanical innovations of the Hellenistic period—such as those of Ctesibius and Hero of Alexandria—demonstrate that the ancient world was not far removed from making limited forms of automation a reality. Hero’s Automata, for instance, describes temple doors that open on their own and theatrical machines that perform elaborate movements through steam and counterweights.16 These mechanical devices, although simpler than Talos in mythic scale and intelligence, point toward a continuous tradition of attempting to animate matter through human ingenuity. Talos, then, can be seen as the imaginative apex of this tradition—a mythical projection of the dreams of early roboticists. His narrative foreshadows both the aspirations and anxieties associated with artificial constructs: awe at their potential and fear of their consequences. Ultimately, Talos and his mythological kin mark the genesis of the idea that humans—or gods, by extension—could replicate life through craft. The ancient Greeks conceptualized automata not simply as mechanical novelties but as beings with assigned purposes, moral implications, and potential vulnerabilities. Talos is a precursor to modern robots not only because he moves on his own, but because his existence raises enduring questions: Can a machine possess agency? Should a creation be bound to the will of its creator? What are the consequences of artificial life? These questions resonate today in debates about AI, robotics, and the ethics of machine autonomy. By exploring these ideas millennia ago through myth, the Greeks laid a conceptual foundation for how later cultures would approach technology and its role in society. Talos thus stands not just as a mythic sentinel, but as a symbolic ancestor of our most advanced machines.

Ethical and Philosophical Implications

The myth of Talos raises profound ethical and philosophical questions about the nature of artificial beings and the responsibilities of their creators. Though mythological, Talos’s status as a mechanical entity created to serve and protect foregrounds concerns that resonate with modern discussions of artificial intelligence, automation, and ethics. Talos was built not as a companion or thinker, but as an unyielding executor of law and violence—his sole purpose was to patrol the island of Crete and destroy invaders.17 This deliberate design presents the earliest version of what might be called an “instrumental intelligence”: an entity whose entire function is defined by others, without self-determination. The ethical tension lies in the stripping of agency from a being capable of action. If Talos can choose targets, defend territory, and inflict death, is he simply a tool, or does his autonomy demand moral consideration?

This leads to a deeper philosophical question: can agency exist without consciousness? Talos reacts to stimuli and performs complex tasks, but he lacks reflection, emotion, or apparent volition. Ancient myths were not explicit about these distinctions, yet they implicitly explored them. The Greeks were familiar with the idea of automaton—self-moving things—and often used such concepts to probe the limits of life and personhood.18 Talos, though lacking in human features, nevertheless walks, perceives, and decides—a trifecta of traits associated with sentient life. The implication is that the ancients recognized the ethical paradox of creating a being capable of consequential actions but denied the moral status granted to living creatures. This foreshadows debates in AI ethics today, where questions about responsibility and accountability surround machines programmed to act independently in human affairs, particularly in military and judicial applications.

The method of Talos’s defeat by Medea also reveals ancient anxieties about manipulation and control. Medea does not fight Talos physically; she deceives him, exploiting what we would now call a security vulnerability. By convincing him to remove the bronze peg that sealed his life-giving ichor, she causes his death.19 This detail mirrors contemporary concerns about the susceptibility of artificial systems to hacking, behavioral manipulation, or design flaws that lead to failure. The myth offers a metaphorical warning: the more complex the machine, the more critical the safeguards. The ancients may not have used terms like “ethical design” or “cybersecurity,” but the myth of Talos embodies the same core issue—powerful tools can become dangerous when not understood or protected. Medea’s cunning also raises moral questions about the boundaries of warfare and whether deception against an artificial being constitutes ethical conduct.

There is also a moral ambiguity in Talos’s role as an enforcer of order. On one hand, he protects Crete, providing safety and stability; on the other, he executes intruders without trial or mercy. This kind of blind justice raises philosophical concerns akin to those posed by algorithmic decision-making today. If machines enforce law without room for interpretation or compassion, do they uphold justice or undermine it? The Greeks, by embedding this question in a myth, suggest discomfort with automated enforcement untempered by human judgment.20 Talos is effective but inhumane, precise but unreflective. This dichotomy reflects the broader philosophical theme in Greek thought: that unmoderated force, even when technically just, can lead to tyranny or moral error. Talos’s lack of moral nuance reflects the dangers of creating beings that operate according to pure function, devoid of the ethical checks that guide human actors. Lastly, Talos’s myth is a meditation on the hubris of creating life. In Greek thought, hubris often referred not just to arrogance, but to the transgression of natural limits, especially those dividing mortals and gods. By crafting Talos, Hephaestus crosses that boundary, constructing not merely a machine, but a quasi-living being with the power to kill. This act echoes Promethean overreach—the appropriation of divine prerogatives by creators seeking to rival nature.21 That Talos ultimately falls suggests a cautionary theme: artificial life, no matter how powerful, is vulnerable, and its creation carries unforeseen consequences. Ancient myths were rarely prescriptive, but they often warned of the dangers of overreaching ambition. Talos, in this respect, functions both as technological marvel and moral lesson—an enduring symbol of the double-edged sword of innovation.

Conclusion

Talos stands as a compelling ancient precursor to artificial intelligence. Though couched in the language of myth, his form, function, and fatal flaw embody the same concerns that dominate AI discourse today: autonomy, control, vulnerability, and ethical responsibility. Far from being mere fantasy, the story of Talos illustrates that the concept of intelligent machines is not exclusively modern, but rather a long-standing human fascination. Ancient mythmakers, in their depiction of Talos, were grappling with ideas that would take millennia to manifest in physical reality. Their stories continue to resonate, reminding us that every technological leap must be accompanied by philosophical reflection.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, trans. Richard Hunter (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 4.1638–1693.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca, 1.9.26.

- Homer, Iliad 18.370–385; see also Homer, Odyssey 7.87–91.

- Marina Warner, Monsters of Our Own Making: The Myths of Enduring Evil (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007), 45–52.

- Carl A. P. Ruck and Danny Staples, The World of Classical Myth: Gods and Goddesses, Heroines and Heroes (Durham: Carolina Academic Press, 2001), 266–268.

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, 4.1690–1693.

- Adrienne Mayor, Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), 33–36.

- Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 4th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2021), 15–16.

- Luciano Floridi and Josh Cowls, “A Unified Framework of Five Principles for AI in Society,” Harvard Data Science Review 1, no. 1 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.8cd550d1.

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, 4.1690-1693.

- Warner, Monsters of Our Own Making, 51-52.

- Mayor, Gods and Robots, 25-29.

- Homer, Iliad 18.370–385; see also Odyssey 7.87–91.

- Ibid.

- Pseudo-Aristotle, On Marvelous Things Heard, 842b; see also Ruck, The World of Classical Myth, 134–135.

- Hero of Alexandria, Pneumatica, trans. Bennet Woodcroft (London: Taylor Walton and Maberly, 1851), 1–12.

- Mayor, Gods and Robots, 38-42.

- Deborah Kamen, “Automatons and Ethics in Ancient Greek Thought,” in The Ancient Mediterranean World: From the Stone Age to A.D. 600, ed. Robin Osborne (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 211–213.

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, 4.1690-1695

- Warner, Monsters of Our Own Making, 54-56.

- Jenny Strauss Clay, “Prometheus and the Technology of the Gods,” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 94 (1992): 121–136.

Bibliography

- Apollonius of Rhodes. Argonautica. Translated by Richard Hunter. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Clay, Jenny Strauss. “Prometheus and the Technology of the Gods.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 94 (1992): 121–136.

- Floridi, Luciano, and Josh Cowls. “A Unified Framework of Five Principles for AI in Society.” Harvard Data Science Review 1, no. 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.8cd550d1.

- Hero of Alexandria. Pneumatica. Translated by Bennet Woodcroft. London: Taylor Walton and Maberly, 1851.

- Homer. The Iliad and The Odyssey. Translated by Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin Classics, various editions.

- Kamen, Deborah. “Automatons and Ethics in Ancient Greek Thought.” In The Ancient Mediterranean World: From the Stone Age to A.D. 600, edited by Robin Osborne, 205–215. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Mayor, Adrienne. Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus. The Library. Translated by James G. Frazer. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1921.

- Pseudo-Aristotle. On Marvelous Things Heard. In The Works of Aristotle, edited by W. D. Ross. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1908.

- Ruck, Carl A. P., and Danny Staples. The World of Classical Myth: Gods and Goddesses, Heroines and Heroes. Durham: Carolina Academic Press, 2001.

- Russell, Stuart, and Peter Norvig. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2021.

- Warner, Marina. Monsters of Our Own Making: The Myths of Enduring Evil. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.26.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.