Dictatorship thrives not only on the whip and the gun, but on the frame and the filter. To study their images is not to indulge in aesthetics, but to read the language of power itself.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Cult of the Modern Strongman

The rise of authoritarianism in the early twentieth century unfolded not solely on the battlefield or through legislative fiat, but also in the hearts and minds of the people—an arena increasingly shaped by mass media and aesthetic manipulation. Fascist and totalitarian regimes, often associated with brute force and repression, were equally invested in an artful performance of legitimacy. Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Joseph Stalin, while ideologically distinct, all understood a truth as old as empire: that rule is secured not only by fear, but also by spectacle. Each dictator cultivated a mythic persona, crafted for public consumption and tailored to the demands of emerging modern audiences.

This essay explores the symbiotic relationship between power and image in the twentieth century’s most notorious regimes. It considers the orchestration of propaganda not simply as a tool of coercion, but as a strategic aesthetic enterprise—one that merged classical symbolism, modern public relations, and the mechanical reproduction of charisma. From Hitler’s Wagnerian rallies to Mussolini’s futurist fantasies and Stalin’s socialist realism, these leaders framed themselves through carefully constructed media ecosystems. In doing so, they established a blueprint for authoritarian image-making that would echo far beyond their lifetimes.

Hitler and the Choreography of Consent

Aesthetics of Authority

Adolf Hitler’s mastery of spectacle was neither accidental nor peripheral to his regime—it was central. With Joseph Goebbels at the helm of the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, the Nazi state functioned as both a political machine and a cultural factory. The regime’s obsession with visual coherence, architectural scale, and choreographed mass participation transformed the Führer from man into myth. Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935), with its sweeping aerial shots and rhythmic montages of synchronized soldiers, framed Hitler not merely as a national leader but as the embodiment of divine destiny.1

The Nuremberg Rallies exemplified what historian Jeffrey Herf has called “reactionary modernism”2—a paradoxical fusion of high-tech modernity with premodern romanticism. Hitler, arriving from the clouds in a plane, descending into a sea of torch-bearing youth, was less a politician than a messiah descending from the heavens. Every camera angle, every column of soldiers, every swastika-laden banner contributed to the creation of what Susan Sontag later described as “fascist aesthetics”:3 the aestheticization of politics to generate emotional submission.

Managing the Messenger

What made Hitler’s propaganda so insidiously effective was its multifaceted targeting. Domestically, it played upon the anxieties of a humiliated postwar population, turning national resentment into a redemptive fantasy. Internationally, the regime sought to sanitize its image through more subtle means. American and British journalists were given tightly controlled tours of “model” concentration camps, such as Theresienstadt, staged to appear as humane retirement colonies.4 Nazi diplomats in London and Washington distributed pamphlets extolling Germany’s technological progress and peace-loving intentions. Even as the machinery of death expanded, the image of a disciplined, revived Germany was broadcast to foreign audiences.

Mussolini and the Theater of the Modern Roman

The Illusion of Modernity

If Hitler embodied a spectral futurism cloaked in medieval grandeur, Mussolini cast himself as the living heir to Roman glory. His fascist state was not merely political; it was performative. Mussolini’s image was cultivated as a hypermasculine, athletic, virile leader—riding horses, swimming, fencing, and flying airplanes. As Ruth Ben-Ghiat notes, Mussolini was “Italy’s first modern media-savvy politician,” using newsreels, radio, and architecture to position himself as both everyman and Caesar.5

The regime’s architectural ambitions echoed its political narrative. The EUR district of Rome, a grandiose construction project begun in the 1930s, fused neoclassical monumentality with fascist rigidity. The very stones of the city were co-opted into Mussolini’s image: eternal, unyielding, and reborn.

The Public as Performer

Fascist Italy mobilized its citizens not merely to obey, but to participate in a national performance of order and unity. The Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro (OND), a state-sponsored leisure organization, offered concerts, sports, and theatrical productions—each laced with fascist messaging.6 This integration of ideology into daily life blurred the line between the private and political, making the individual complicit in the state’s theatrical project. The state became not just a ruler but a producer, and the people, its cast.

Stalin and the Curation of Memory

From Man to Monument

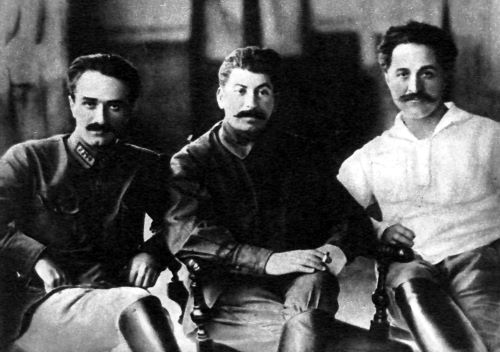

While Hitler and Mussolini were obsessed with the presentational now, Stalin was a master of historical manipulation. His propaganda enterprise focused less on spectacle and more on erasure, redaction, and substitution. Photographs were doctored to remove purged officials; encyclopedias were reprinted to reflect shifting orthodoxies. Stalin did not simply cultivate an image—he cultivated a past.

Socialist realism, the mandated aesthetic of the Soviet Union, presented Stalin as a paternal, omnipresent figure: stoic, wise, and surrounded by children or factory workers. Public statuary and murals mirrored religious iconography. In these portrayals, Stalin was never a man of blood but a man of steel—temperate, just, and timeless.

The Dialectic of Visibility

Yet Stalin was also careful to remain partially hidden. He rarely appeared in public, preferring controlled portraits and staged meetings. This calculated invisibility lent him an aura of mystery. His physical withdrawal from the public stage paradoxically magnified his symbolic presence. As theorist Boris Groys has argued, totalitarian aesthetics operate on a dialectic of excess and absence.7 The leader is everywhere and nowhere; known through images, yet unknowable in essence.

Global Echoes and Contemporary Refrains

The tactics pioneered by these twentieth-century regimes have not faded. In fact, they have been repurposed for new authoritarian contexts. Modern strongmen employ global public relations firms, manipulate digital media, and stage-managed press events to craft sanitized images. Vladimir Putin’s shirtless horseback photos, Xi Jinping’s soft-focus factory visits, and even Kim Jong-un’s Disneyesque public appearances reflect a persistent grammar of autocratic presentation. Image management, once a tool of newspaper ink and film reels, now thrives on algorithms and influencer economies.

While the mediums have evolved, the principles remain: control the narrative, craft the spectacle, curate the memory. In the authoritarian playbook, image is not peripheral to power. It is power.

Conclusion: Image as Instrument, Persona as Policy

Authoritarian regimes of the twentieth century understood that control over perception was as essential as control over territory. In Hitler’s symphonies of steel and fire, Mussolini’s romantic nationalism, and Stalin’s autocratic retouching of history, we find not merely propaganda but performance. The spectacle was not the shadow of the regime—it was its face.

The enduring lesson is sobering. Dictatorship thrives not only on the whip and the gun, but on the frame and the filter. To study their images is not to indulge in aesthetics, but to read the language of power itself.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Leni Riefenstahl, Triumph of the Will, directed 1935.

- Jeffrey Herf, Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture, and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984).

- Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism,” in Under the Sign of Saturn (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1980), 73–105.

- Fred Taylor, The Goebbels Diaries 1939–1941 (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1982).

- Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Fascist Modernities: Italy, 1922–1945 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

- Ibid.

- Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992).

Bibliography

- Ben-Ghiat, Ruth. Fascist Modernities: Italy, 1922–1945. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

- Groys, Boris. The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

- Herf, Jeffrey. Reactionary Modernism: Technology, Culture, and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- Sontag, Susan. “Fascinating Fascism.” In Under the Sign of Saturn, 73–105. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1980.

- Taylor, Fred. The Goebbels Diaries 1939–1941. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1982.

- Young, James E. The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.15.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.