A subtle hybrid born of ancient Chinese manufacturing skills and a Western desire for the exotic.

By Dr. Helen Clifford

Owner and Curator, Swaledale Museum

Museum Consultant, University of Warwick

Introduction

Made from bast fibres (material made from the inner bark of trees, such as paper mulberry and blue sandalwood) and backed with a thicker paper made of bamboo fibres, laminated together with starch, Chinese wallpaper was (and still is) hand painted in vivid colours, sometimes with the aid of block-printed outlines, with flowers, foliage and birds, and more rarely with scenes from Chinese life.1 The history of Chinese wallpaper is inextricably linked to that of the East India Company (EIC) in whose ships it travelled from Canton (mod-ern Guangzhou) to London. It remains a distinct and luxury product to this day. Chinese wallpaper was rarely closely imitated by competing European manufactures (unlike porcelain or the lacquer that spawned ‘japanned’ wares); it did not accommodate Western fashion cycles like cotton; it remained a small scale private trade, retaining its elite status, distinct identity, and high price over time.2 Its acquisition was as likely to come through gifting as through purchase, and Chinese wall-paper thus avoided becoming a ‘new consumer commodity’. Although associated, like porcelain, with feminine desire and female spaces, it appears in drawing and billiard rooms as well as ladies’ bedrooms, in public as well as private arenas. These very problems of positioning create opportunities for reconsidering the contemporary experience, and later evaluation, of Asian goods in domestic contexts.

In his exploration of design and the domestic interior in England, Charles Saumarez Smith observed that, in the late seventeenth century ‘the most visible sign of new wealth, and an obvious target for social crit-icism, was the import of luxury goods from the Far East’ and instanced as examples the impact of lightweight Indian chintzes, translucent porcelain and glossy lacquered furniture.3 The curator Oliver Impey added Chinese wallpaper and carpets to the porcelain and lacquer, considering them the four most prominently displayed categories of goods imported from the East.4 It would be a mistake however to assume that these goods followed similar pathways from point of manufacture to country house, moving over time from collectors’ rarities to commonplace commodities, and eventually overtaken by their imitators. The case of Chinese wallpaper challenges any overarching or simplistic model of production, export and consumption.

The aim of this contribution is to examine the impact that Chinese wallpaper made on the British country house, where its presence has been seen by many as its defining feature. Although we know that it was hung in homes that were not country houses, like that of the actor Samuel Foote (1720–77), who had bought it for the private rooms of his London residence, surviving evidence connects most Chinese wallpaper in Britain with the country house.5 Examples have been located across the British Isles, from Blair Castle in Pitlochry, Scotland to Penrhyn Castle in North Wales, from Clyne Castle in South Wales to Tregothan deep in Cornwall.6 In the east of England there are fine examples including those at Ickworth in Suffolk and Houghton Hall in Norfolk, while Ireland boasts papers in both the north and south.7 In the sheer surface area it covers within the home, it can claim to be the dominating decorative element of a room, setting the style and acting as a backdrop for the country house interior as stage. It is frequently mentioned in diaries, letters and guidebooks both past and present, indicating its high visibility and distinctiveness, and appears in widely differing and often surprising sources and contexts. Yet its high profile within the con-sumer context is not matched by records of its manufacture, export and sale on its route from Chinese workshop to country house within the legendary detail and scale of East India Company archives. Neither is there any comprehensive study of these wallpapers, although this will soon be remedied with the publication of the proceedings of the Chinese Wallpaper: Trade, Technique and Taste conference, which brought together curators, conservators, country house owners and scholars to consider European, American and Chinese perspectives in London in 2016.

In the following contribution the evolution of Chinese wallpaper will be mapped, reflecting this luxury good’s birth as a subtle hybrid born of ancient Chinese manufacturing skills and a Western desire for the exotic. Its key characteristics compared with its European counterparts will then be considered, in order to understand its unique qualities. The rest of the paper will explore the pivotal role that the East India Company played in the dissemination of Chinese wallpaper through the country houses of Britain. This role is best understood through an examination not of hard, quantifiable trade facts but of the soft, flexible and opaque web of associations that defined the influence and networks of East India Company employees, whose connections spread far and wide.

The Evolution of Chinese Wallpaper: The Story from East and West

Exotic wall coverings were used to decorate the homes of the wealthy in Europe, long before the invention of wallpaper. Available to a select few, these precursors of wallpaper included embossed leathers, tapestries and woven damasks. The earliest European papers were printed on single sheets of paper. A fragment found in Christ’s College, Cambridge was printed on the reverse of a recycled proclamation issued by Henry VII. It is the earliest known example of English wallpaper, and was probably hung after 1550.8 In the later seventeenth century individual black and white wooden block printed papers became popular.9 Later, sheets of rag paper were glued along the edges to form a roll, ground colour was applied by hand before printing on designs with wood blocks and/or stencils using distemper pigments. This became the formula for English wallpaper production until the mid-nineteenth century.10

The Chinese of course also used paper in their homes, but it was quite different in size, format and design to that made for the West. We know surprisingly little about the use of the plain, coloured and patterned paper that furnished Southern Chinese interiors, where it was customary to paste the windows of houses with plain paper and sometimes to paint this decoratively. Perhaps these were the papers that John Evelyn noted in 1664 when he admired ‘a sort of paper … with such lively colours, that for splendour and vividness we have nothing in Europe that approaches it … [it is], exceeding glorious to look on’, that had accompanied goods brought back from China by a Jesuit.11 It is thought by some that the appreciation of such ornament by European visitors might have prompted the Chinese to produce similar work for export. It is more likely however that the Chinese wallpapers we know in the West originated from the less familiar wall decorations on paper created in China especially for export to Europe.12

Chinese pictures and prints were imported in small quantities first by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, and then into France by Dutch traders, towards the end of the seventeenth century.13 The earliest precise reference to the import of graphic art from China to England is 1727.14 There is a later but very informative description of these pictures by Robert Fortune (1812–80) the plant hunter, who took the tea plant from China to India. Fortune observed in the house of a mandarin ‘a nicely furnished room according to Chinese ideas, that is, its walls were hung with pictures of flowers, birds, and scenes of Chinese life. … I observed a series of pictures which told a long tale as distinctly as if it had been written in Roman characters’.15 These pictures continued to be popular in Britain and were used alongside Chinese wallpaper. For example Lady Cardigan bought 88 ‘Indian pictures’ in 1742, which were pasted over the walls of her dining room.16 Nearly 30 years later there is a description of a dressing room at Fawley Court, Henley-on-Thames decorated with ‘the most curious India paper as birds, flowers etc., put up as different pictures in frames of the same’.17

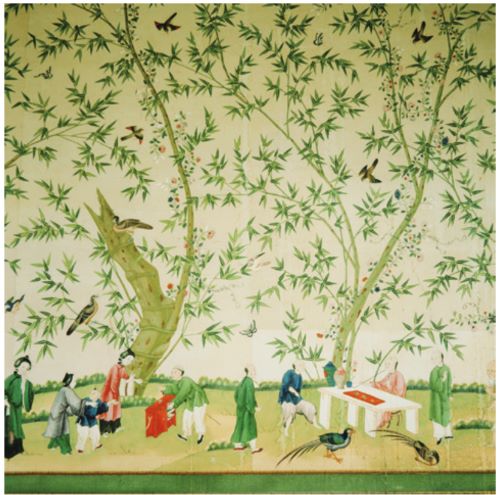

Contesting a deceptively simple and linear trajectory of development, Emile de Bruijn has persuasively suggested that the Western taste for Chinese pictures and prints which developed in the late seventeenth century stimulated European designers and craftsmen to produce wallpapers with imitation Asian motifs at the beginning of the eighteenth century. It was only then, he suggests, that Chinese painting workshops responded to that demand by producing pictorial wallpapers from the 1730s–1740s, like those at Felbrigg in Norfolk and Dalemain in Cumbria (see Figure 1).18

This may explain why, although one of the first mentions of Chinese wallpaper appears in 1693 in an advertisement in the London Gazette for the sale of ‘paper hangings of Indian and Japan figures’, it is only from the mid-eighteenth century that any of these Chinese papers survive in Europe.19 The heavy weight, rough surface, crude and repetitive printing and limited palette of the early European wallpaper formed a rather drab contrast to the light, soft, flexible and smooth Chinese wallpapers, colourfully painted with endlessly varied scenes, which began to appear in the West. The wallpaper was made using ancient techniques pioneered in China in the eighth century bce, in production-line workshops in Guangzho (Canton) and involved many specialized hands, responsible for block printing outlines to hand painting, using the same methods, and probably the same skilled workforce, that worked on silk.20

This paper was more widely known in Britain, until the mid-nineteenth century, as ‘India hangings’ in recognition of the power and influence of the EIC which held the monopoly on its importation, and on whose ships it travelled to Europe. The name also reflected the older European custom of covering walls in textile hangings, and the wider attraction of all things exotic, which did not include an interest in their precise place of origin. Although the techniques of manufacture were ancient, the product was new and created specifically for export to Europe. The number and range of sources mentioning Chinese wallpaper increased over the first half of the eighteenth century. John Macky’s description of his visit to the Palace of Wanstead, built by Sir Richard Child in 1720, is typical of the growing awareness of this new type of furnishing. He includes a reference to the parlour ‘finely adorned with China paper, the figures of men, women, birds and flowers the liveliest I ever saw come from that country’.21

Through an analysis of 149 Chinese wallpapers located across Britain, gathered by Emile de Bruijn and Andrew Bush as part of the Chinese Wallpaper Study Group, it has been possible to divide these papers into three types.22

The following analysis relies heavily on this pioneering attempt to discern patterns of change and preference. Papers decorated with flowering trees and plants, birds, insects and rocks, representing idealized gardens were more popular (and more affordable), accounting for 95 papers, that is 60 percent of all examples collated (see Figure 2).

These kind of papers appeared from the mid- eighteenth century, and have continued in popularity ever since. Much more unusual were the papers decorated with figures in landscapes engaged in agriculture and industry, showing buildings and gardens and festivals, which account for 15 percent of the 149 listed, which appeared at the same time as the ‘idealized garden’ papers described above (see Figure 3).

Another distinctive and identifiable group are those papers which incorporate figures at the bottom edge, with trees and bamboo, which appear from the 1790s (see Figure 4). The remaining 15 percent relate to Chinese pictures used as paper, either separately or deployed in groups as collage and which are found up until 1800.

Since the publication of this study in 2014, another 20 Chinese wallpapers have been discovered in Britain.23 The British fascination with Chinese wallpaper ebbed and flowed over the centuries, but has never disappeared. Although it reached the height of its popularity between the 1750s and the 1770s, it was revived in the 1820s–1850s, and was rediscovered in the 1920s. Although there are signs of changes in style, for example the introduction of paper that created a ‘print room’ effect in the 1780s, Chinese wallpaper – to Western eyes – seems to have remained timeless, complementing interiors that were successively rococo, neoclassical, empire and even antiquarian (see Figure 5). Today old Chinese wallpapers make good prices at auction, and new ones are being made to satisfy the demand for the exotic, expensive and unusual in the interior.24

What were the distinctive characteristics of Chinese wallpaper, the features that set it apart from its European counterparts, ultimately protecting it from widespread import substitution? It was unmatched for its colour and texture. It came in non-European dimensions, accommodating non-repeat mural-like and diverse designs, which appealed to an enlightened audience seeking an idea of what China was really like, as well as satisfying the unquenchable thirst for exotic fantasy, while retaining its cachet of rarity and expense.

Malachy Postlethwayt (1707(?)–67) in his Universal Dictionary of Trade and Commerce (1757) ascribed the popularity of Chinese export paintings to their colours, diversity and fantasy. ‘The pictures’, he wrote ‘are valued for the liveliness and briskness of the colours and variety of figures’.25 The same criteria could also be applied to Chinese wallpaper, which as we have seen, was so closely associated with these export paintings. Like the textiles with which they were associated, including Indian-made chintz, Chinese wall-paper was admired in the West for its colour. We know that many interiors combined the two materials, for example at Harewood House, near Leeds the room with the ‘Chints [bed] Hanging lined with silk’, was hung with Chinese wallpaper. This was a European-wide phenomenon. In Italy the casinos were ‘neatly fitted up with India paper, and furnished with chintz’.26 Hargrove and Bewick described the best bedchamber at Newby Hall, near Ripon in 1789 as ‘hung with India paper, on which the flowers and foliage, birds and other figures, are represented in the most lively and beautiful colours’.27 Here the word ‘lively’ indicates vibrancy of colour. Admiration for this attribute did not wane over time. In 1825 these papers were still described as ‘glowing and brilliant’.28 Even though many surviving wallpapers have suffered from deterioration by light, some still glow with bright blues, greens and reds (see Figure 6).

For example the figural and floral paper now in the sitting room at Powis Castle, near Welshpool retains its green background, while bright red berries look ready to pick.29 Unable to match this brightness of colour on such a scale, European wallpaper makers like John Baptist Jackson (1695–1777) cast doubt on its virtues, dismissing ‘the gay glaring colours in broad patches of red, green yellow blue etc which are to pass for flowers and other objects’ because, although they delighted the eye, they had no ‘true judgment’, that is good taste.30 In 1810 R. Phillips’s most damning criticism of a flower painting was to liken it to ‘Chinese paper hangings … striking to the vulgar eye, that always delights in gaudy tints’.31

It was not, however, only the colour of Chinese wallpaper that seduced westerners, but also its smoothness, opacity and uniformity, akin to the European fascination with porcelain and silk.32 Thanks to the work of expert paper conservators we know that these admired characteristics were achieved by coating the support paper onto which the design was executed with a white pigment bound in animal glue dusted with alum or mixed with mica, giving it a shimmering appearance like silk. This type of paper coating was developed in China in the fourth century ce which not only had an aesthetic purpose but also a practical one, in that it aided the absorption of the inks, which were used to form painted and block printed outlines, that were filled in with colour.33

Chinese wallpaper usually came in up to 40 lengths, each roll measuring 3.5m by 1m, sometimes with discernible numbers that indicated the sequence in which it should be hung. Although Chinese wallpaper was made for the European market, it never seems to have been manufactured to European dimensions, not even for special commissions. The problems that resulted demanded inventive solutions, as extensive modifications made to Chinese wallpapers at the point of installation prove. Additions were made to top and base, as at Felbrigg, where the bottom was cut in a wavy line to obscure the join; and cut-outs pasted on to hide joins, as at Erdigg in Wrexham where 3cm flies have been applied, or at Ickworth where butterflies have been pasted onto the paper (see Fig. 2.6). Some examples show evidence of skies painted in, as well as strips added at the base, like the paper at Milton Manor, in Oxfordshire. At Blickling in Norfolk individual paper lengths were reduced in width and height, the original sky was cut away and a replacement with the addition of a mountain and trees painted in on an additional layer of western-made paper. At Ightham Mote in Kent, when the supply of Chinese paper ran out, sections of Indian printed silk were added. In some cases European printed borders were supplied to frame the Chinese wallpaper, as at Woburn in Bedfordshire and Belton in Lincolnshire.34 Postlethwayt, it will be remembered, admired the ‘diversity’ of Chinese wallpaper, compared with its European counterparts. This can be interpreted in two ways, in relation to the design of single papers (that is the lack of repeats), and across papers (that is, the scarcity of duplicates).35 Although the use of wood block out-lines in earlier papers meant that the same motifs can be identified on Chinese wallpapers now hung across the country, the individual hand-colouring of them ensured they were never exactly the same. These techniques of production created an impression of uniqueness, the admiration of which may explain why the Chinese moved from block-printed outlines to hand-painting, which enabled even more flexible production.

For the European consumer Chinese wallpaper satisfied two seemingly contradictory attributes. It was admired both for the accuracy of its depiction of Chinese life – its people, activities, and flora and fauna –as well as for its fantasy. The distinguished botanist, Sir Joseph Banks (1743–1820), observed in his journal in 1770:

‘A man need go no further to study the Chinese … than the China paper, the better sorts of which represent their persons and such of their customs, dresses, etc., as I have seen, most strikingly like, though a little in the caricatura style. Indeed, some of the plants which are common to China and Java, as bamboo, are better figured there than in the best botanical authors that I have seen’.36

Yet while some ‘read’ Chinese wallpaper as an accurate narrative, others like Postlethwayt noted that it satisfied the desire for ‘Odd fancies [that] commonly hit the general taste, and the Chinese do not seem to have any fancy for pieces of gravity’.37 There is only one known surviving example of a Chinese wallpaper made to a European design, from engravings by the French designer of ornament Gabriel Huquier (1695–1772) after the French painter Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), made for Hampden House in Buckinghamshire, and hung around 1756.38 The practice of supplying models and patterns from Europe, for production in China, (as in the case of Chinese armorial porcelain), never seems to have been adopted for wallpaper.

Part of the attraction of these papers was their rarity. As Lady Mary Coke commented in 1772, ‘I have taken down the Indian paper, put up another upon a blue ground with white birds & flowers: ‘tis very pretty & has the additional recommendation of being quite new. There are but eight sets come to England’.39 Her note ‘come to England’ refers to the annual arrival of the EIC ships in London, which took advantage of the north-east monsoons, arriving home between November and March. A return expedition from London to Canton took an average of eighteen months, and in the 1700s the Company was making 20 to 30 sailings to East Asia each year. Supplies of Chinese wallpaper were therefore limited, which added to their desirability, and expense. Lady Anna Miller noted in 1776 that ‘India paper is more expensive in England than dam-ask here [in Italy]’.40 At Croome Court in Worcestershire the bills for the ‘29 fine India landscapes’ of 1763 sent to Lord Coventry reveal each landscape cost £2 2s, making a total of £60 18s. This would have bought a smart new coach.41 It was so expensive, offcuts were kept, as at Penryhn Castle, Gwynedd, and old papers removed and put into storage.42 Its cost and rarity meant that it was more likely to be left on a wall, than stripped off when fashions changed. While middle-class home owners were exhorted to change their wallpaper every few years, these expensive papers tended to survive, their appeal seemingly eternal, shielding them against the relentless cycles of changes in fashion.43 While novelty might have been part of their original appeal, when old they acquired a value of their own, and like the scenes they depicted evoked a timelessness that made a satisfying counterpoint to a Western world that was perceived to be increasingly governed by change.44

East India Company Connections

Although imported by EIC ships, Chinese wallpaper, like hand-painted silk (and rosewood furniture, mirror paintings and armorial porcelain) was solely part of the privilege trade, and never undertaken by the Company, at least for the English EIC.45 This trade was instead part of the allowance given to employees, such the captains and supercar-goes (the merchants who were responsible for the cargo, its purchase and sale, and the commercial concerns of the voyage) who although paid modest salaries, were permitted to trade on their own account to specified levels, enabling the most successful to increase their income thirty-fold.46 As Meike von Brescius has noted ‘The size and scope of the private trade in Chinese export wares during the first half of the eighteenth century has been greatly underestimated’, and the official documentation that does survive is fragmentary.47 The Company derived income from every private trade good that passed through its public sales, as it accrued warehouse fees, handling charges and commission paid by the importer.48 Although we know that some Chinese wallpaper arrived through this privilege route – it bears auction house marks – much bypassed it, being declared ‘gifts’ or objects ‘of personal use’, thus sidestepping documentation.49 As the Chinese export porcelain historian David Howard reminds us ‘These private traders were socially and financially in touch with wealthy private clients, who might often be related by blood, and it was they who elected the most fashionable products available at Canton by carrying special commissions. They gained a much wider understanding of what was available, which knowledge was in turn, at the disposal of the Company’.50 In some cases, although not with Chinese wallpaper, the Company, seeing the success of privately traded goods at auction, might decide to add them to the EIC trade, prohibiting or limiting them from private trade.

Yet we need to put this private trade in context. It accounted for a small percentage of the whole trade with China, and Chinese wallpaper made up only a small proportion of this. Furthermore as Jan de Vries has demonstrated, even the official Company trade (which focused on tea and textiles) only equated, by the later eighteenth century, to around 50,000 tons per year (equivalent to the capacity of one mod-ern container tanker).51 What was important about these goods was not their volume, but the impact they made, which was quite disproportionate to their number. These distinctive luxury goods were undoubtedly part of wider fashion whereby ‘persons of quality and distinction, who had Taste and all that’, were advised to ‘have something foreign and superb’.52 Of the 149 Chinese wallpapers located in Britain for the Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses project, it is clear that a significant number, at current calculation 20 percent, were connected with individuals and families boasting traceable links with the EIC.53 It is more than likely that many more from this survey had such associations, as yet unidentified.

It is rare to be able to connect the arrival of a Chinese wallpaper in a country house with a specific person. One of the exceptions relates to James Drummond, 8th Viscount Strathallan (1767–1851) who brought his Chinese wallpaper back with him from Canton. Drummond was a nephew of the London banker Robert Drummond of Cadland, Hampshire, and prospered in the service of the EIC in China. He began his EIC career as a supercargo, and became assistant to the Head of the Committee at Canton in 1792, and by 1800 he was a member of the Select Committee there. The following year he became President, a post he held until 1807 when he returned to Scotland. The 18 rolls of 12-foot by 4-foot mulberry bark and bamboo paper are hand-painted with a scene of the ‘hongs’, or foreign factories at Canton (Guangzhou), which enable its dating to c.1790. These ‘factories’ were not places of manufacture, but mercantile warehouses, where the foreign merchants were allowed to operate. The paper would thus have had a very personal meaning to Drummond, who would have resided in the British ‘factory’ on the waterfront at Canton. However when it arrived at Strathallan Castle in Perthshire it was not put up in his private rooms, but on the walls of the Ladies’ Salon, where it stayed for almost 200 years, before it was acquired by the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts.54

A significant proportion of the Chinese wallpapers that survive, and which can be connected with the EIC, relate to its Directors. On its foundation in 1600 the Company was led by one Governor and 24 Company Directors who sat on its Court. While the Company ruled millions of people, and employed a vast army of officials abroad, it operated from tiny headquarters in London, staffed by only 159 men in 1785 and 241 in 1813. Unlike Drummond, few of the Directors had actually worked in or even visited China. However due to their position of power and influence they had privileged access to the luxuries imported by the Company, via their enviable and often complex network of contacts. Henry Lascelles Senior (1690–1753), Collector of Customs in Bridgetown, Barbados, for example served as a Director of the East India Company between 1742 and 1746. Henry’s youngest son, also called Henry, became a Captain for the EIC and by 1741 was in command of a ship called the York. Over the next seven years Henry made three trips to the port of Canton. However it has not been possible to make a direct link with these trips and the Chinese wallpaper that hung in the East Bedroom at Harewood House in 1769, which belonged to Henry’s brother Edwin, 1st Baron Harewood, who built the house between 1759 and 1771. At Harewood it was more the wealth gained from West Indian sugar plantations than profits from the East India trade that contributed to its creation. However the two sources of income, and access to goods, were inextricably entwined in the formation of this and many other country houses across Britain.55

At Erdigg in Wrexham the Chinese wallpaper in the State bedroom, may have been installed during the modernization of the house in the 1770s by Philip Yorke (1743–1804) and his wife Elizabeth (1750–79), daughter of Sir John Cust of Belton. It is possible that the Chinese wallpaper was supplied by Elizabeth’s uncle, Peregrine Cust (1723–85) who was deeply involved in East India Company affairs, becoming a Director in 1767. When Agneta York wrote in 1772 that the bedrooms and dressing rooms at Osterley were furnished ‘with the finest chintzes, painted taffetys, india paper and decker work and such a profusion of rich China and Japan that I could almost fancy myself in Pekin’, she was acknowledging the fruits of three generations of owners who had close connections with the Company, as attested by the chapter in this volume on Osterley House and Park.56 The Chinese wallpaper at Broughton Castle, c.1850 which bears similarities to those at Belton, Burton Constable, Ickworth, Penrhyn, and Woburn, may have been introduced by Frederick Twistleton, 16th Lord Saye and Sele (1799–1887), as he refurbished the Castle in the 1860s.57 The family had close connections with the EIC via the 13th Lord Saye and Sele (c.1735–88). His wife, Elizabeth Turner was the heiress of Sir Edward Turner whose Company wealth funded the restoration of Broughton. Edward Turner’s mother, Mary, was the daughter of Sir Gregory Page (c.1669–1720) a London merchant whose wealth partly stemmed from the EIC, of which he was a Director.58 As can be seen from these examples it was often the connections of the women of a family, as much as that of the men, who were responsible for making available Asian privilege trade goods for the British interior.

Another level of association with the EIC came via its investors. Some owners of Chinese wallpaper, like Edward Howard, 9th Duke of Norfolk (1686–1777) can be identified as EIC shareholders, although it has not been possible to link the wallpaper which decorated the principal bedrooms of his properties of Norfolk House, St James’s Square, and at Worksop Manor, with specific ships. So despite this wealth of potential connections between the Company and Chinese wallpaper it is frustratingly difficult to link surviving papers with East Indiamen and Company personnel, and the houses which they graced. To do this we need to turn to the Russells, Dukes of Bedford, whose family archive sup-plies a wealth of EIC related material, and whose major country house, Woburn, retains much of its original furnishings. (The Bedford Russells are not related to the Russells of Swallowfield Park featured elsewhere in this volume, notwithstanding the two families shared surnames and Company connections).

The associations of the Russells and the EIC covering six generations from the 1st to the 6th Dukes of Bedford, are revealed in successive waves of Asian influence on their patterns of collecting and decorating.59The wealth of Chinese wallpapers (and other Asian decorative goods) relating to Bedford property combined with the survival of household accounts and letters documenting their shipping, purchase and installation are a uniquely rich source of information.60 Study of the Bedfords’ patronage of the arts (both fine and decorative) has until recently been restricted to European sources, revealing the hierarchy of interest that has dominated decorative arts research.61 When there are 21 paintings by Canaletto at Woburn why bother with the Chinese wallpaper? Yet when the close connections of the Bedford family with the East are drawn out, it is clear that their Chinese wallpapers were intimately bound up with their fortunes, and valued across generations.

The Dukes of Bedford used their position as owners of East Indiamen hired to the Company, and as investors to gain privileged access to these Asian goods. The marriage of the 1st Duke of Bedford’s grandson Wriothsey Russell, Lord Tavistock (1680–1711) to Elizabeth Howland (1682–1724) in 1695 brought a spectacularly large dowry of near £100,000 (roughly equivalent to £9 million today) into the family whose estates included Thames-side property at Rotherhithe. The marriage also connected the Russells with the Childs of Wanstead House, as Elizabeth was the granddaughter of Sir Josiah Child (1630–99) whose advocacy of the EIC’s monopoly led directly to his appointment as a Director in 1677, rising to Deputy-Governor and Governor of the Company in 1681.62 At Rotherhithe the 1st Duke of Bedford (1613–1700) built the first docks, whose rental brought in a useful income, first from the Greenland, and then the South Sea Companies. At these docks he built the Streatham which was presented by his grandson to the EIC. The Bedford, Tavistock, Russell and Howland followed, all commissioned before 1700, to which were added the Tonqueen, and later the Houghton and Denham.63 The Bedfords invested between one-sixteenth to one-eighth part in the voyages these vessels took, and thereby had considerable holdings in the East India Company.

When John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford (1710–71) began remodelling and redecorating Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire and Bedford House in London in 1748, he combined Chinese wallpaper and ceramics with new Louis XV-style furniture and portraits by British artists. Tracking their purchase reveals the ways these exotic commodities, including wallpaper, entered the British home. The Green Drawing Room at Woburn, now known as the Ballroom, is hung with a hand-painted Chinese wallpaper of c.1800–20. When this wallpaper was conserved in 1998 two separate inked inscriptions were found on the back of the wallpaper. ‘Royal George’ refers to the ship that transported the wallpaper from China to England, and ‘No 48’ may refer to the package and ‘46 sheets’ to its contents.64 ‘Lot 25’ is written in a different hand and confirms it was consigned to auction at East India House, and comprised ‘24 sheets’. This shows that the original consignment was divided, which suggests that another set was made from the remaining 22 sheets.65 There were five ships named the Royal George which made voyages between 1737 and 1822; the one conveying the wallpaper was a 1,333-ton ship that made seven voyages between 1802 and 1817.66 This wallpaper relates to the 6th Duke’s (1766–1839) campaign of re-decoration.

Another route via which Chinese wallpaper entered the Bedford homes, was purchase from a range of specialist shops, not confined to, but predominantly in London. The paper in ‘His Grace’s Bedchamber’ at Woburn was bought from the London wallpaper suppliers Crompton and Spinnage in 1751–52, at a cost of £60 13s 10d (a similar price to that purchased for Croome Court), part of a larger bill for hanging Chinese wallpapers at Woburn of £253 13s 10½ d. It is one of the earliest known Chinese wallpapers to survive, contemporary and similar to those at Felbrigg Hall in Norfolk, Ightam Mote in Kent and Uppark in West Sussex. It was still there in 1771 when it was described in an inventory of that year as ‘Hung with India Paper’.67

The Russells clearly liked their Chinese wallpaper, as it was also used at Oakley House, in Bedfordshire, not far from Woburn and at Endsleigh Cottage in Devon. After the purchase of Oakley House (built between 1748 and 1750) by the 4th Duke in 1757, the old house was demolished and a new one was built on the site, serving as a hunting box for successive Dukes. The 1935 sale catalogue lists three rooms clad with Chinese wallpaper, on the ground floor smoking room, the stair-case hall and in the first floor bedroom. One of c.1790, survives. They were probably related to the 5th Duke’s influence, who employed Henry Holland to modify Oakley for him. The paper for Endsleigh Cottage, which was hung in the main guest bedroom, may have been bought at the same time as that for the Green Drawing Room at Woburn. This was one of a number of Chinese wallpapers at Endsleigh. The house was built between 1810 and 1816 by John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford as a private family residence, to the designs of Sir Jeffry Wyattville, as a grand form of the cottage orné, where house and landscape were designed as one. It was usefully positioned to serve as a residence whilst the Duke, normally residing at Woburn Abbey, was inspecting his extensive Bedford estates in Devon and Cornwall. It was the Duke and Duchess’s favourite residence and was used for entertaining intimate friends.68

The Chinese wallpaper in the Russell residences was part of a wider strategy of furnishing which included Chinese porcelain and silk, and Indian furniture (all either acquired before the 4th Duke’s time, or made in the style of this period). These interiors were a constant reminder of the family’s links with the EIC, which dated back, as we have seen earlier, to the 1st Duke, and through it, to the wider world. Chinese wallpapers appeared in their grand country house at Woburn, as well as in their smaller retreats. These furnishings demonstrated the family’s power to access these goods over several generations. As Lucy Johnson has noted, this engagement with Asian goods, via their EIC connections, was underpinned by a deeper fascination with the culture of China, evidenced by the 4th Duke’s purchase ‘from 1735 onwards [of books] which covered virtually every aspect of Chinese history, life and culture’.69 The 5th Duke went on to build a Chinese Dairy at Woburn, designed by Henry Holland in 1787, decorated by John Crace, and completed in 1794. Humphrey Repton supplied designs for a Chinese gar-den at Woburn in 1804–5. The 6th Duke employed Sir Joseph Banks to advise and acquire Chinese plants for his gardens, and bought as many Chinese wallpapers as the 4th Duke.

Gifts and Gifting

There was another route which Chinese wallpaper took from the workshops of Canton to the country houses of Britain. The gifting of Chinese wallpaper dominates their history, although it is difficult to verify any of the stories connected with their presentation. It has been suggested, although not substantiated with evidence, that ‘sets of painted wallpaper were specially created by Chinese merchants to give as gifts to finalize deals with their European trading partners’.70 Within a culture that placed great emphasis on ritualized gift-giving, this strategy appears plausible. Perhaps having started life as gifts, there was a stronger likelihood that these wallpapers should then continue their life as gifts once they reached the West. It gave them a special status, embedded them in a narrative that was told and retold through the generations. Through gifting, these expensive commodities slipped their economic context, and gained a separate and higher level of existence. The reciprocity of a business transaction, for example the purchase of Chinese wallpaper from a London shop, was both immediate and specific, a self-enclosed episode, while acquisition by gift was more complex. The latter enhanced and complicated their value, influenced the site of installation and attitudes of reception. The last part of this contribution examines some of these gifting episodes.

Although it has been impossible to verify any of these gifting ‘stories’, whatever their truth, they indicate that they were given a high status, especially when the gifting was connected with royal favour. It is from the 1780s that the narratives of ‘imperial’ and ‘royal’ gifts of Chinese wallpaper begin to appear, perhaps as a reaction to the increasing availability of wallpaper from the 1750s, in an attempt to make some papers more distinct than others. Charlotte Abrams reporting in a recent fashion magazine warns readers ‘that the trend [of hanging expensive wallpapers] is so ubiquitous it is becoming increasingly tricky to keep ahead of one’s paper-buying friends’.71 Surely the same such worries also engaged wealthy house owners of the eighteenth century? How much greater was the value of a set of papers that came with its own story and unique connections? It helped set it apart from others.

The earliest record of the gift of Chinese wallpaper found so far is connected with the royal physician Dr John Turton (1736–1806).72 A man of ample fortune even before he was appointed in 1771 as George III’s doctor, Turton had duties that included the delivery of numerous royal babies. His role made him a great favourite of Queen Charlotte. On his retirement in 1786, Turton left Adam Street, in the Adelphi, where he had been a neighbour of the actor David Garrick, and bought Brasted Place in Kent, which he immediately demolished and began rebuilding and decorating with the assistance of Robert Adam.73 Of the several royal favours he received, one included ‘a wallpaper which had originally been sent by the Emperor of China as a present to King George III and was bestowed on Dr Turton by the Queen’.74 This paper therefore had a doubly inflated status. Some accounts say the paper was put up in the billiard room, others in the drawing room, although the latter was more likely. The paper was recorded in situ at Brasted by English Heritage, where it is described as ‘2 panels of Chinese wallpaper depicting scenes of everyday life’, some removed to Kent Museum.75 Papers depicting this type of scene, and those illustrating Chinese manufactures, were more expensive than other types of Chinese wallpaper, such as those with trees and birds. It has been shown earlier, using data from Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses, that these papers accounted for only 15 percent of the total of known wallpapers.76 Hence this royal gift was distinguished further by the rarity of its design.

A gift of Chinese wallpaper is said to have been the impetus for the creation of Brighton Pavilion between 1787 and 1826. Whether or not it is true that the paper was a gift to the Prince Regent, the story itself suggests a desire to root this fantastical construction in a response to ‘real’ Chinese sources.77 Other decorative goods like Chinese porcelain, furniture and other decorative objects, were acquired via John and Frederick Crace who were responsible for negotiating with the Custom House for their importation. Gordon Lang reminds us that Frederick Crace took an ‘almost slavish adherence to original Chinese sources, using motifs from eighteenth century ‘famille-rose’ export ware porcelain, Canton enamel and even Mandarin robes’; and asks if in his scheme whether he was following the wishes of the Prince of Wales?78 There are three different Chinese wallpapers at the Pavilion, none of which is early enough to be the paper that supposedly inspired the project: one c.1790, acquired in 1815, and hung in 1820 in the Adelaide corridor; one c.1815 part of Frederick Crace’s scheme for the Saloon;79 and one hung in Queen Victoria’s bedroom when she resided there between 1835 and 1845. (The wallpaper currently in this bedroom is a recent facsimile).

Perhaps it was from the earliest cache of Chinese wallpaper that the Prince Regent made his gift in 1806 to the feisty Frances Ingram, Lady Irwin (1734(?)–1807) of Temple Newsam in Leeds, as an indication of his affection for her eldest daughter Isabella, Marchioness of Hertford (1759–1834), who became his mistress the following year. It was she who had the paper hung, 20 years later, in 1827, creating the Blue Drawing Room (also known as the Chinese Drawing Room) out of what had been the best dining room at Temple Newsam. She embellished its design with 28 hand-watercoloured exotic birds cut from 10 loose prints from John James Audubon’s The Birds of America whose first volume appeared in the same year that the wallpaper was hung.80

It was the popularity of Brighton Pavilion that was responsible for a second wave of interest in Chinese wallpaper which began in the 1820s. After visiting the Pavilion Marianne, Lady Clifford Constable and her sister Eliza were inspired to create their own Chinese Room at Burton Constable, in East Yorkshire. The walls were hung with new Chinese wallpaper (originally a powdered pink colour), while stencilled designs were added to doors and walls, and silvered bells hung from the cornice and doorway.81 During the removal of the wallpaper in 1992 as part of a conservation project, an earlier Chinese wallpaper of the 1780s was discovered underneath. This paper can be related to bills paid to Thomas Chippendale’s foreman, William Reid in 1783, revealing a predisposition for Chinese wallpaper that perhaps laid the foundation for the later decoration.

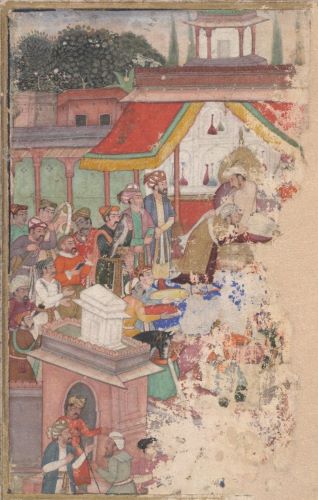

These narratives of multiple gifting lie at the heart of the reception and employment of these Chinese wallpapers, which like their patterns distract and entertain, blending veracity and fantasy to create a magical world of make-believe. The Chinese wallpaper that can be seen in the Board Room at Coutts Bank on the Strand in London today is said to have been a gift to Thomas Coutts (1735–1822) from George Macartney (1737–1806).82 It originally hung in Coutts’s private rooms ‘above the shop’, at 59 the Strand.83 Coutts was an ‘old friend’ of Macartney’s, who organized remittances for him from India, when he was appointed Governor of Madras in 1781.84 This was a position of trust: Macartney relied on Coutts to advise his wife, discharge his debts and dispose of any surplus money to his advantage ‘always taking care it be in such a manner as that I may command it at a moment’s warning’.85 Macartney had been appointed first Ambassador to China, responsible for the trade mission to the Qianlong Emperor in 1793, the total costs (calculated at £95,000) of which were defrayed by the EIC. This was not simply a commercial mission. Facilitating and extending trade were key priorities of both the East India Company and the government, which instructed Macartney to cultivate the friend-ship of China in order to increase ‘the sale of our manufactured articles and of the products of our territories in India’.86 Yet as one of the advisors to the mission, the Birmingham manufacturer Matthew Boulton explained ‘Our knowledge of China is so imperfect that it will be difficult to point out the most necessary articles to send thither. The women are kept so confined that we know nothing of them but from pictures’.87 As a result they were not sure what to send from Britain to tempt Chinese interest.

On arrival in Peking, Macartney and his entourage were given accommodation in the only building large enough to house the whole embassy, the Palace of Eleven Courtyards. This was the home of a Collector of Customs who was in jail awaiting execution for misappropriating the profits of European trade.88 The historian Paul Gillingham states that it was here that Macartney saw the paper that he was to take home to Coutts. From the published journals and diaries of those who were part of the embassy, it is possible to gain some idea of their impressions of the decoration. The pavilions where they were lodged were described by the official recorder of the embassy George Staunton. He noted that they were decorated with paintings, and while some from the mission appreciated them, the general attitude was critical: ‘If a lake is surrounded by houses and trees, the painter does not show the reflection on the water’, and the ‘Distant landscapes seem larger than a house in the foreground and they do not touch the ground’.89 They were not to stay here long however, as the imperial audience was to take place in the emperor’s summer residence 120 miles to the north, at Jehol in Manchuria. In Peking they left behind a team to set up the display of the ‘presents’ and make arrangements for transforming the Palace of Eleven Courtyards into the British embassy.

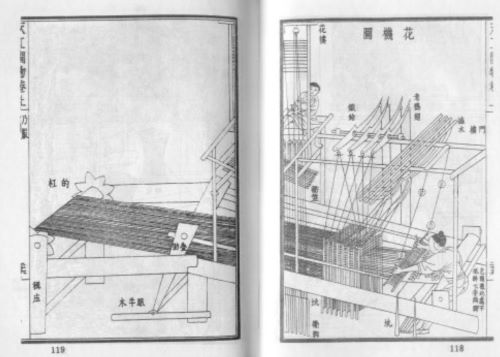

Although the embassy was a failure in terms of establishing trade relations, Maxine Berg argues that it was a success in terms of the gathering of ‘useful knowledge’ about China.90 The Chinese wallpaper that Macartney brought home depicts different Chinese manufactures. Their source was Song Yingxing’s (1587–1666) Tiangongkaiwu published in 1637, an encyclopaedic work which examines numerous aspects of technology and manufacture practiced in China at the time including porcelain production accompanied by detailed woodblock illustrations.91 These illustrations were themselves ‘useful knowledge’. An example of how Chinese wallpaper could convey such useful information is given by William Marshall, in his The Rural Economy of Yorkshire (1788), in which he discusses the origins of the winnowing machine. He notes that ‘We are probably indebted to the Chinese or other Eastern nation, for the invention of this machine. I have seen it upon an India paper drawn with sufficient accuracy, to shew that the draughtsman was intimately acquainted with the uses of it. The Dutch, to whom the invention has been ascribed, imported it, in all probability, from the East Indies’.92 The connection between the scenes of Chinese labour and that of a nation undergoing an agricultural and industrial revolution was drawn upon by Viscount Torrington when he visited Cromford in 1789, the site of Arkwright’s new textile ‘factory’, where ‘There is so much water, so much rock, so much population and so much wood that it looks like a Chinese town’.93 As Clive Aslet has commented ‘it was a whimsical picture’ evoking the contrast made between the busy cotton spin-ners and the wild Derbyshire scenery amid which their industry took place’.94 Yet as Craig Clunas has reminded us, in relation to Chinese export watercolours, the reading of such information is not so simple. ‘Whatever the customer may have thought, he was not buying a piece of reportage, an accurate picture … Nor was he buying a product of Chinese imagination. Rather he was receiving his own preconceptions of the mysterious inland provinces as a land of grotesque and fantastic landscapes, inhabited by ingenious and curious people living an idyllic life of harmony with nature, reflected back at him by an artist whose sole concern was to please’.95

Macartney’s wallpaper depicted an idyllic picture of manufacture at a time when Britain was launching into its own system of factory production. Perhaps there was some irony too in the fact that this paper showed Chinese goods such as porcelain, tea and silk which Europeans were desperately keen to imitate, acquired by an ambassador who had failed to entice the Chinese into buying European goods. The Emperor dismissed the embassy and its gifts explaining that ‘we have never valued ingenious arti-cles, nor do we have the slightest need of your Country’s manufactures’.96

When Thomas Coutts sat in this room above the ‘shop’, the wall-paper that Macartney had given him must have reinforced the global image and ambition of his business. Coutts kept closely in touch with public affairs at home and throughout the world, through leading politicians and by maintaining a close network of Scottish friends and relatives abroad. As Macartney brought him wallpaper from China, so Lord Minto (1751–1814) who was Governor General of India between 1807 and 1813, brought him news from India.97 Coutts had interests in a number of East India Company vessels, two of which were named after him.98

A second failed mission to the Emperor of China, led by William Pitt Amherst (1773–1857) while Ambassador Extraordinary to China in 1816–17, led to the gift of another Chinese wallpaper. It was sent by Amherst to fellow diplomat Henry Chamberlain (1773–1829), who he had visited in Brazil, where Chamberlain was Consul-General. Amherst, writing at sea to Chamberlain in 1817, remembered ‘that at one of your hospitable dinners … the conversation turned upon hanging your dining room with Chinese paper. It will give me the greatest pleasure if the accompanying parcel should be found useful for that purpose. At all events I beg you to do me the favour to consider it as proof that your friendly reception of myself and my companions at Rio Janeiro [sic] was not forgotten by me while I resided at Canton’.99 The value of the gift was enhanced by the miracle of its journey, as Amherst noted in the same letter:

‘I hope the paper will not be found to have suffered any injury from the misfortune which befell the Alceste in the Straits of Gaspar. She was one of the few articles which I was enabled to save from the wreck’.100

The ship which had been chosen to carry Lord Amherst on his 1816 diplomatic mission to China had foundered on its return journey on a reef in the Java Sea where, after the evacuation of passengers and crew, it was plundered and burned by Malayan pirates.101

The gift of Chinese wallpaper from one diplomat to another perhaps helped convey a shared sense of risk that their appointments involved. Amherst’s gift was even more poignant given that the Embassy which he headed, financed by the East India Company and sent to redress interference with trade by the Viceroy of Canton, was a complete failure.102 Amherst never did see the Emperor as the mission was dismissed.103 The Chinese wallpapers that lay at the heart of these missions, as material evidence of superior manufacturing, were witness to both the failure of gift-giving from West to East, and of successful gifting and commerce from East to West.

As noted at the beginning of this article the impact of Chinese wallpaper was nationwide, and reached at least as far as Blair Castle in Perthshire and Eglinton Castle on the north-west coast of Scotland. There are a cluster of Chinese wallpapers in the east, below the Firth of Forth found at Newhailes, Newbyth, Dunglass, Arniston and Bowhill. Perhaps the most well known in this area is at Abbotsford, not because of its rarity, but because it hangs in the home of the celebrated author Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832).104 This was not an aristocratic country house, but a home that was the culmination of Scott’s creative ambitions as a writer and the source of his inspiration for his novels and poems.

The vivid green Chinese wallpaper that hangs in the Drawing Room at Abbotsford in the Scottish Borders might strike the modern visitor as incongruous in a baronial antiquarian interior, created by Scott between 1812 and his death. However its presence not only illustrates the power of the gift, but also how intimately Asian goods and Scottish history could be intertwined. We know that Scott ‘direct[ed] everything personally, connected with the building and decorating of his mansion’, transforming what the locals called Clarty Hole farmhouse into a ‘rambling, whimsical and picturesque’ country house.105 Scott was advised by a close group of male friends: James Skene of Rubislaw (1775–1864), Daniel Terry (1780(?)–1829), Edward Blore (1787–1879), William Atkinson (1773–1839), William Stark (1770–1813) and George Bullock (1782/3–1818).106 Scott’s wife, Margaret Charlotte Charpentier (d.1826) seems to have had little say in the project. As a result we know a great deal about the furnishing of Abbotsford through Scott’s correspondence with his advisors; because of Scott’s fame, we also have the published comments of his workmen and visitors. It is in a letter dated 10 November 1822 to Daniel Terry, that the origin of Abbotsford’s Chinese wallpaper is revealed:

‘Hawl the second is twenty-four pieces of the most splendid Chinese paper … a present from my cousin Hugh Scott, enough to finish the drawing room and two bedrooms’.107

Captain Hugh Scott (1777–1852) was the second son of Walter Scott, Laird of Raeburn (1744–c.1830), Sir Walter Scott’s uncle, who at the time was in the Naval Service of the East India Company. He had been made Captain of the East Indiaman, Ceres, which made several voyages to China, until it was relegated to hulk in 1816. The painting of the ship, in its original frame, remained in the possession of Hugh Scott’s family at Draycott until recently.

This was not the only Chinese wallpaper to hang on the walls at Abbotsford however. Scott’s painter and decorator, Mr Hay, refers in his Laws of Harmonious Colouring adapted to Interior Decoration, (published in 1847) to ‘an Indian paper of a crimson colour with a small gilded pattern upon it’ to complete the decoration of the Dining Room walls at Abbotsford, for which the final plans had been made in 1818.108 This paper may also have come from Scott’s cousin Hugh. Hay remarks that Scott ‘said he did not altogether approve of’ this paper ‘for a dining room, but as he had it in a present expressly for that purpose, and as he believed it to be rare, he would have it put upon the room, thither than hurt the feelings of the donor’.109 This Chinese wallpaper reveals two important points. First, it highlights the presence of a type of wallpaper that is rarely commented upon. It was the floral and figural papers that caught contemporary attention, and we know little about these plainer papers. Scott himself remarked that it was ‘rare’. Secondly, the presence of the wallpaper demonstrates that the power of the gift-giver overrode convention in the hanging of the paper in an ‘inappropriate space’. The National Trust Chinese Wallpaper Project has confirmed the dominance of private spaces such as bedrooms, dressing rooms and drawing rooms (often, but not only, feminine spaces) for such paper, with only very few examples of a paper hung in a dining room, at Abbotsford, and a twentieth-century reproduction made for Avebury Manor. Hay observed to Sir Walter that there would scarcely be enough to cover the whole remainder of the wall after the pictures were fixed up, to which he replied, that if that was the case I might paint the recess of the sideboard ‘in imitation oak’. He noted that ‘Scott abominated the common-place daubing of walls, pan-els, doors and window-boards, with coats of white, blue, or grey. … He desired to have about him, wherever he could manage it, rich, though not gaudy hangings, or substantial old-fashioned wainscot work, with no ornament but that of carving, and where the wood was to be painted at all, it was done in strict imitation of oak or cedar…. He ordered me to paint the dining-room ceiling, cornice, niches &c in imitation of oak to match the doors, window shutters and wainscoting which were made of that wood’.110 These instructions suggest that Scott was making the most of his limited supply of this wallpaper, and that he felt that it needed to be used, not put in store, in recognition of the value of the gift, and the status of the donor in the recipient’s eyes.

The Abbotsford Chinese wallpapers may seem an odd addition to Scott’s antiquarian interior to modern eyes. However it is clear that Asian connections and influences percolated throughout the house, and indeed through Scott’s own family and friends, as well as through his work, most notably in The Surgeon’s Daughter (1827). Sir Walter resided for many years at Ashestiel, near Selkirk, the home of his cousin General Sir James Russell who was then in India. It was not only Scott’s cousin Hugh who had ties with the East India Company. His brother Robert died young while serving with the EIC in India. Sir Walters’s nephew, Walter Scott (1807–76), the only son of Thomas Scott, spent a considerable portion of his youth under the immediate care of his uncle. At the age of 17 he entered the service of the East India Company as a lieutenant in the Engineers. He attained distinction in the Mooltan campaign (1848–9), and was, in 1861, promoted as Major-General, and in 1875 as General.111 His brother-in-law Charles Charpentier (later Carpenter) was also a Company servant, finally taking up residence in the Madras estates in Salem, where he died in 1818. Scott’s eldest son Walter (b.1801) became a Lieutenant General in the 15th Dragoons, and served in Bangalore until his death in 1847.112 Scott’s younger son Charles (b.1805) died in Tehran, in 1841, while part of a Foreign Office mission to the Court of Persia.

Abbotsford boasted an armoury, adjoining the dining room, which was described in 1818 as including ‘the armour of true celebrated Jalabad Sing Son of Nadior Shah (1688–1747)’ as well as ‘pretty complete suits of armour – one Indian … and the clubs and creases of Indian tribes’, alongside those of Highlanders’ accoutrements.113 The ‘curious antique ebony chairs’ in the Drawing Room, were Indo-Portuguese, c.1800 and were combined with furniture from the Palace of Falkirk. Sir Walter Scott also had a connection, if remote, with Thomas Coutts. In his Life of Scott, Lockhart (Scott’s son-in-law and biographer) remarks that ‘Sir Walter’s grandmother, Barbara Haliburton, wife of Robert Scott of Sandyknowe, was the banker’s first cousin’.114 The story of Walter Scott and his Chinese wallpaper emphasizes the crucial importance of how complex relations with the East India Company could be. Mediated through the agency of friends and relatives, the exotic could be drawn into the fabric of the interior, overcoming what appear to us contradictions in taste to create richly nuanced spaces, where ancient oak furniture shared space with Mughal armour and Chinese wallpaper.

Concluding Remarks: Afterlife

Chinese wallpaper illustrates the myriad ways in which East India Company trade pervaded British social and cultural life, shaping the domestic interior in fundamental ways. Although the papers themselves were (and still are) conspicuous in their colouring, patterns and design, their pivotal roles in globalizing the British home have received little systematic attention. The impact of Chinese wallpaper was not restricted to those who had houses decorated with it, or had access to these houses as visitors and servants. Despite the success of British-made wallpapers, the allure of Chinese wallpaper continued beyond the nineteenth century. Its high value ensured that this exotic and fashionable luxury item survived beyond redecoration. Offcuts and scraps were framed as pictures, used to ornament chimney boards (at Osterley, a Chinese print was used with an applied border), or deployed to back embroidered pole screens and craft work. Chinese wallpaper was used to cover boxes, and larger sections were turned into screens.115

In the 1920s and 1930s Nancy Lancaster invented the ‘English Country House Style’, and one of its crucial components was Chinese wallpaper, which was ‘sold both as rooms and panels’ and spawned ‘a cottage industry of talented copyists’ whose handiwork has deceived many a country house visitor.116 The fascination with Chinese wallpaper continues into the twenty-first century. The firms of de Gournay and Fromental create handmade papers in Wuxi, the latter supplying 22 panels for Avebury Manor based upon the Coutts and Drummond papers, which took 12 Chinese artists 4,000 hours to make. Meanwhile Lord Macartney’s gift of paper to Thomas Coutts, has become a symbol of the bank’s distinguished heritage, parts of which have been copied to furnish key rooms in each of their offices around the world. The paper is a key marketing tool that conveys both the stability of its eighteenth-century foundations and the reach of its global connections.

Endnotes

- Emile de Bruijn, Andrew Bush and Helen Clifford, Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses (Swindon, 2014), 4.

- There are very few known examples of European made chinoiserie style wallpaper that look like the Chinese wallpapers made for export. One of these came from Berkeley House, Wotton-under-Edge, Gloucestershire c.1740, now in the V&A: W.93:1–63–1924.

- Charles Saumarez Smith, Eighteenth-century Decoration Design and the Domestic Interior in England (London, 1993), 48.

- Oliver Impey, ‘Eastern Trade and Furnishing of the British Country House’, in Gervase Jackson-Stops (ed.), The Fashioning and Functioning of the British Country House, Studies in the History of Art, 25 (Washington, DC, 1989), 177.

- Ian Kelly, Mr Foote’s Other Leg: Comedy, Tragedy and Murder in Georgina London (London, 2013), 382. As Emile de Bruijn noted in a remark on this contribution, the fewer examples of Chinese wallpaper in town as opposed to country houses may reflect a higher rate of rebuilding, sale and exchange in the latter.

- These houses contain not just Chinese wallpaper but many other examples of Asian decorative art. For example the dining room at Tregothan, seat of the Boscawen family since the fourteenth century, contains a K’ang vase supposedly brought back by Admiral Boscawen from Pondicherry in 1749. See Stephanie Barcezewski, ‘Is Britishness always British?’, in M. Farr and X. Guegan, The British abroad since the Eighteenth Century, vol.1, Travellers and Tourists (Heidelberg, 2013), 45.

- This mapping has been made possible by the Chinese Wallpaper Study Group, see de Bruijn et al., Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses, 10–11.

- Of formalized pomegranate design, derived from a contemporary Italian velvet or damask, see: Textile influences on wallpaper: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/textile-influences-on-wallpaper/.

- For example woodblock print on paper, late seventeenth-century found on an early seventeenth-century box now in the V&A Museum (E.405–1968), showing a scene of a seated figure fishing before a pond, a house in the backgrounds, with trees and flowers and birds, set within a border, measuring 39.5 cm by 49.5 cm.

- When the tax on paper was lifted in 1861, wood pulp began to replace rags, and new technology enabled the production of continuous sheets of paper which could be printed faster.

- Henry G. Bohn, Diary and Correspondence of John Evelyn, vol. 1 (London, 1859), 402–403.

- I. Lambert & C. Laroque, ‘An Eighteenth-century Chinese Wallpaper: Historical Context and Conservation’, in ‘Works of art on paper: books, documents and photographs: techniques and conservation: contributions to the Baltimore Congress’, 2–6 September 2002,122–128. See: https://www.iiconservation.org/node/2002.

- Quoted G. L. Hunter, Decorative Textiles: An Illustrated Book on Coverings for Furniture, Walls and Floors (Philadelphia, 1918), 363.

- Craig Clunas, Chinese Export Watercolours (London, 1984), 10.

- Robert Fortune, A Residence among the Chinese (London, 1865), chap. 4.

- Quoted in Margaret Jourdain and Soame Jenyns, ‘Chinese Export Art in the Eighteenth Century’, Country Life (1950), 34.

- Emily J. Climenson (ed.), Diaries of Mrs Philip Lybbe Powys of Hardwick House, Oxon (London, 1899), 146–147, entry for October 1771, quoted by Gill Saunders, Wallpaper in Interior Decoration, (London, 1994), 49, note 15.

- Emile de Bruijn, Chinese Wallpaper in Britain and Ireland (London, 2017), 30.

- London Gazette, 16–20 March, quoted in Jourdain and Jenyns, ‘Chinese Export Art’, 25.

- It was ‘probably hand painted in the same workshops in Canton since the technique to stain wallpapers was very similar to the preparation of hand painted silks’ see Saunders, Wallpaper, 50.

- John Macky, A Journey through England (London, 1724) vol.1, 21.

- See de Bruijn et al., Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses, 10–11.

- de Bruijn, Chinese Wallpaper in Britain and Ireland, 30.

- Two companies dominate the supply of Chinese wallpaper in Britain today: de Gournay founded 30 years ago by Claud Cecil Gurney and Fromental established by Tim Butcher and Lizzie Deshayes in 2005.

- Quoted in Andrea Feeser, Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin, The Materiality of Color: The Production, Circulation, and Application of Dyes and Pigments, 1400–1800 (London, 2012), 86.

- Lady Anna Miller, Letters from Italy, Describing the Manners, Customs, Antiquities, Painting, vol. 2 (London 1776), 358.

- E. Hargrove, The History of the Castle, Town and Forest of Knaresborough with Harrogate (4th ed., York, 1789), 265.

- A. J. Valpy, ‘On the Life and Times of Casimir’, The Classical Journal, 31 (1825), 308.

- de Bruijn et al., Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses, cat. no. 36, p. 39. This paper was moved from Walcot Hall in North Shropshire, (purchased by Robert Clive in 1764) to Powis in 1936.

- Quoted in A.V. Sugden, A History of English Wallpaper 1509–1914 (London, 1914), 56.

- R. Phillips, Monthly Magazine and British Register, 30: 2 (1810), 199.

- Pauline Webber, ‘Chinese Wallpapers in the British Galleries’, V&A Conservation Journal, 39 (2001), 6.

- Webber, ‘Chinese Wallpapers’, and her paper ‘The Conservation and Restoration of Chinese Wallpapers: An Overview’, given at the ‘Chinese Wallpaper: Trade, Technique and Taste International Conference’, Coutts Bank and V&A, London 7–8 April 2016.

- See de Bruijn et al., Chinese Wallpapers in National Trust Houses, and Johnson, Peeling Back the Years.

- Although it has been possible to identify repeat motifs, such as the ducks which appear on the paper at Ightham Mote, Belton and Woburn, see de Bruijn et al., Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses, 30.

- J.D. Hooker (ed.), Journal of the Rt Hon Sir Joseph Banks (New York, 1896), vol.4, 45.

- Malachy Postlethwayt, The Universal Dictionary of Trade and Commerce (London, 1757), 56.

- John Cornforth, Early Georgian Interiors (New Haven and London, 2004), 265–6.

- The Letters and Journals of Lady Mary Coke, vol.4 (Bath, 1970), 43.

- Miller, Letters from Italy, 23.

- Liza Picard, Dr Johnson’s London (London, 2001), 297.

- Gill Saunders, ‘The China Trade: Oriental Painted Panels’, in Lesley Hopkins (ed.), The Papered Wall: History, Pattern Technique (New York, 1994), 42–55, with thanks to Andrew Bush for this reference.

- Margaret Ponsonby, Stories from Home: English Domestic Interiors, 1750–1850 (Aldershot, 2007), 53.

- A. Fennetaux, A. Junqua and S. Vasset, The Afterlife of Used Things: Recycling in the Long Eighteenth Century (London, 2015), 3.

- There is evidence that other East India Companies did experiment with official as opposed to private trade in Chinese wallpapers, thanks to research undertaken as part of the ‘Europe’s Asian Centuries’ project at the University of Warwick 2010–14, funded by the European Research Council, and led by Maxine Berg. According to Chris Nierstrasz the Dutch East India Company (VOC) imported 200 pieces in 1757 as part of the official trade, although this does not seem to have tempted them to develop the trade further. Information relayed in a private communication to the author in 2014, based on his work for his book Rivalry for Tea and Textiles: The English and Dutch East India Companies (1700–1800), (Basingstoke, 2015). Felicia Gottman’s work on the French East India Company for the same project reveals that in a memorandum written in the 1730s a Company ship’s captain noted ‘there are more than 50 different sorts of paper made in China, the one from Nankin is however the most highly esteemed – it is also from where the best painted ones come’, the latter presumably referring to wallpaper, which was also auctioned by the Company in 1768. Private communication from the author, June 2014.

- See further, ‘The Honourable East India Company trading to China’ in David S. Howard, A Tale of Three Cities: Canton, Shanghai & Hong Kong (London, 1997), xiv.

- Meike von Brescius, ‘Worlds Apart? Merchants, Mariners and the Organisation of the Private Trade in Chinese Export Wares in Eighteenth-Century Europe’, in Maxine Berg et al. (eds), Trading Eurasia: Europe’s Asian Centuries 1600–1830 (Farnham: 2015), 71–2.

- Meike Fellinger (von Brescius), ‘The Principal-agent Problem Revisited: Supercargoes and Commanders of the China Trade’. Accessed 2 September 2016. http://studylib.net/doc/13209578/the-principal-agent-problem-revisited–supercargoes.

- Meike Fellinger (von Brescius), ‘Supercargoes and the English East India Company in the China Trade 1700–1760’ (PhD thesis, University of Warwick, 2015).

- Howard, Tale of Three Cities, xiv.

- Jan de Vries, ‘Goods from the East’, in Berg et al. (eds), Trading Eurasia, 30.

- The World, 1:38 (20 September 1753), 242.

- Based on an ongoing database, part of the National Trust Chinese wallpaper project, which at March 2014 included 149 houses, 30 of which have East India Company connections.

- He also acquired amongst other things a porcelain ‘Palaceware’ dessert service, c.1795 which also travelled back with him to Scotland. See Howard, Tale of Three Cities, cat. no. 41, 47–8. With thanks to Emile de Bruijn for this reference. The Castle had been in the Drummond family since the thirteenth century. It was sold in 1910 to Sir James Roberts, in whose family it remains today. The Chinese wallpaper was purchased by the Peabody Essex Museum with funds donated in part by The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund, 2006. See further William R. Sargent, ‘The Strathallan Castle Wallpaper at the Peabody Essex Museum’, Orientations, 45: 8 (2014), 22–23.

- See further The Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership, http://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/.

- See Yuthika Sharma and Pauline Davies, ‘ “A jaghire without a crime”: East India Company and the Indian Ocean Material World at Osterley 1700–1800’, in this volume.

- With many thanks to Emile de Bruijn for his very helpful comments on this wallpaper.

- See information included in the entry on Sir Edward Turner (1719–66) in L. Namier and J. Brook, The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1754–1790 (London, 1964) via online resource: http://www.histparl.ac.uk/volume/1754–1790/member/turner-sir-edward-1719–66.

- The following taken from Gladys Scott Thomson, The Russells in Bloomsbury 1669–1771 (London, 1940), 312–338.

- See Lucy Johnson, Peeling Back the Years: Chinoiserie at Woburn Abbey (Bedford, 2014).

- For example Denys Sutton (ed.), Treasures from Woburn Abbey from the Collection of the Duke of Bedford, originally published in Apollo Magazine (December 1965).

- See Hannah Armstrong’s case study ‘Josiah Child and the Wanstead Estate’ at http://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/eicah/josiah-child-and-the-wanstead-estate-case-study/.

- Thomson, The Russells, 316.

- One of the duties of a supercargo was ‘to cause every package in private-trade to be marked with the initial of the name of the person to whom it belongs, register them with these marks, the nature of the package, the contents, and quality of the contents’, Rule CIV (Instructions from the Commanders of The East India Company’s Own Ships to Their Officers, &c (London, 1819), 39.

- Information kindly supplied by Lucy Johnson, 29 June 2014.

- Jean Sutton, Lords of the East: The East India Company and its Ships (London, 1981), 166.

- The Chinese paper in this room at Woburn was protected by another layer of paper added 28 years later when the room was redecorated, and was rediscovered in 2014.

- Johnson, Peeling Back the Years, 3.

- Johnson, Peeling Back the Years, 4.

- Gill Saunders, Wallpaper in Interior Decoration (London, 2002), 3.

- http://howtospendit.ft.com/interior-design/25123-wall-important.

- In 1771 he was appointed physician to the Queen’s household; in 1782, physician in ordinary to the Queen, and physician extraordinary to the King; and in 1797, physician in ordinary to the King, and to the Prince of Wales.

- Extended in the nineteenth century by Alfred Waterhouse, now converted into seven apartments.

- E. Jordan, ‘Chinese Wallpapers in England’, The Star, Issue 9680 (23 October 1909), 1.

- Listed 1954, English Heritage Building ID 356912. Also described as ‘illustrating the different arts and manufactures of the Celestial empire’, in J. Cave-Brown, History of Brasted, Its Manor, Parish and Church, vol.II (Westerham, 1874), 284.

- De Bruijn et al., Chinese Wallpaper, 3.

- Christina Baird, Liverpool China Traders (Bern, 2007), 136.

- See Gordon Lang, ‘The Royal Pavilion, Brighton: The Chinoiserie Designs by Frederick Crace’, in Megan Aldrich (ed.), The Craces, Royal Decorators 1768–1899 (Brighton, 1990), 43.

- The wallpaper noted here in the Saloon was not original to this space, and has now been removed and replaced by another, red silk scheme as at 2016. With many thanks to Emile de Bruijn for this information revealing the complexities related to the mobility of the wallpaper.

- The Birds of America was first published as a series in sections between 1827 and 1838 in Edinburgh and London. The work consists of hand-coloured, life size prints, made from engraved plates. The plates were published unbound and without any text to avoid having to furnish free copies to English libraries. It is estimated that not more than 200 sets were ever completed.

- Avray Tipping, ‘In English Homes: The Internal Character, Furniture & Adornments of Some of the Most Notable Houses of England’, Country Life, 2 (1908), 150.

- Helen Fetherstonhaugh, Three Hundred Years of Private Banking (London, nd), 21.

- He acquired the lease of number 59 and designed a premises specifically for banking.

- Helen Henrietta Macartney Robbins, Our First Ambassador to China: An Account of the Life of George, Earl of Macartney, with Extracts from His Letters, and the Narrative of His Experiences in China, as Told by Himself, 1737–1806 (Cambridge, 2011), 442.

- See book of copy letters BL, Add MS 22462 letters between Coutts, Lord Macartney and Lady Macartney, with thanks to Margot Finn for this reference.

- Maxine Berg, ‘Britain, Industry and Perceptions of China: Matthew Boulton, “useful knowledge” and the Macartney Embassy to China 1792–94’, Journal of Global History, 1 (2006), 268.

- Berg, ‘Britain, Industry and Perceptions of China’, 280.

- Paul Gillingham, ‘The Macartney Embassy to China, 1792–94’, History Today, 43 (1993), 5.

- G. L. Staunton, An Authentic Account of an Embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China (London, 1797), 155.

- Berg, ‘Britain, Industry and Perceptions of China’, 268.

- Thanks to Anna Wu for this information.

- William Marshall, The Rural Economy of Yorkshire: Comprizing the Management of Landed Estates, and the Present Practice of Husbandry in the Agricultural Districts of that County, vol. 1 (London, 1788), 282.

- C. Bruyn Andrews (ed.), The Torrington Diaries Containing the Tours through England and Wales of the Hon. John Byng (Later Fifth Viscount Torrington) between the Years 1781 and 1794, vol. 2 (London, 1935), 40.

- Clive Aslet, The English House: The Story of a Nation at Home (London, 2008), 131.

- Clunas, Chinese Export Watercolours, 14.

- Quoted in Catherine Pagani, Eastern Magnificence & European Ingenuity: Clocks of Late Imperial China (Ann Arbor, 2001), 74.

- Philip Beresford and William D. Rubinstein, The Richest of the Rich: The Wealthiest 250 People in Britain since 1066 (London, 2011), 302.

- National Maritime Museum: BHC3664.

- British Library, Letter dated 23 May 1817, Mss Eur. B376.

- British Library, Letter dated 23 May 1817, Mss Eur. B376.

- See manuscript account in the form of an autograph letter from the carpenter on board HMS Alceste to his father, [c.1817], details from sale at Christie’s, King Street, London, 26–27 September, 2007, lot 507.

- Henry Ellis, Journal of the Proceedings of the Late Embassy to China (London, 1817).