Ancient rituals and philosophical dialogues prefigure modern therapies, while technologies from trephines to smartphones mediate the therapeutic encounter.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The history of mental health treatment reflects humanity’s shifting understanding of the mind, body, and spirit. Across cultures and epochs, societies have grappled with what later came to be called “mental illness,” framing it variously as divine punishment, humoral imbalance, nervous disorder, or neurochemical dysfunction. Correspondingly, the forms of therapy and counseling devised ranged from ritual incantations to talk therapies, from bloodletting to electroconvulsive shock, from trephination to psychopharmacology. Technologies, whether surgical drills, asylum architecture, or modern neuroimaging, have both embodied and advanced these paradigms. To trace this trajectory from the ancient world to the present is to witness the entanglement of culture, medicine, and power in the treatment of the psyche.

Ancient World

Ritual Healing and Spiritual Counsel

In Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Levant, disorders of mood and behavior were often attributed to demonic possession or divine disfavor.1 Therapies involved ritual purification, incantations, and priestly counseling. Egyptian medical papyri describe both physiological and spiritual approaches, prescribing amulets as well as herbal remedies for melancholia-like symptoms.2 Such treatments reveal early recognition that words, rituals, and relationships could be therapeutic in themselves.

Greek Philosophy and Humoral Medicine

Greek medicine reframed mental distress within naturalistic theories. Hippocrates posited that melancholia stemmed from an excess of black bile, advocating diet, exercise, and bloodletting as treatments.3 At the same time, philosophers such as Socrates and Aristotle recognized the healing power of dialogue, foreshadowing later forms of talk therapy.4 The Asclepian temples combined prayer, dream interpretation, and rudimentary counseling, marking an institutionalization of mental healing.

Roman and Other Ancient Practices

Roman physicians like Galen elaborated humoral theory, while Stoic philosophers advanced cognitive approaches, advising that rational self-discipline could counter disordered emotions.5 Outside the Mediterranean, Indian Ayurvedic texts classified mental disorders and prescribed herbal treatments and meditation, while Chinese medicine emphasized qi imbalance, deploying acupuncture and herbal remedies.6 Technologies employed in these contexts included trephination, observed across cultures, wherein skull drilling sought to release malevolent spirits.

Medieval and Early Modern Periods

Religious Healing and Demonology

In medieval Europe, mental illness was often framed within a Christian cosmology of sin and possession. Monastic communities provided what we might call counseling through confession and spiritual guidance.7 Yet exorcism and penitential rituals were also deployed, revealing the ambivalence between care and coercion. In Islamic medicine, scholars such as Avicenna synthesized Greek and Arabic traditions, describing melancholia and mania and recommending music, baths, and compassionate care, anticipating humane therapy.8

Asylums and Confinement

By the late medieval period, the institutionalization of mental health took architectural form. Hospitals like the Bethlehem Hospital (“Bedlam”) in London became sites of confinement rather than therapy.9 Technologies here included not only the physical restraints of chains and manacles but also the architecture of isolation itself. Yet charitable traditions also fostered “mad houses” that offered rudimentary shelter and care.

Renaissance Humanism and Counseling

The Renaissance rediscovered classical texts, reviving humoral medicine but also encouraging humanist counseling. Physicians like Johann Weyer argued against witchcraft accusations, attributing supposed possession to mental illness, an early defense of psychiatric compassion.10 Counseling here intersected with philosophy and theology, showing the persistence of talk-based healing traditions even amid coercion.

Industrial and Scientific Era

Moral Treatment and Early Psychotherapy

The late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries witnessed a shift toward “moral treatment.” Philippe Pinel in France and William Tuke in England advocated for humane care, freeing patients from chains and emphasizing conversation, work, and structured environments.11 Technologies included new asylum designs intended to create order and tranquility, reflecting a belief in architecture as therapy. Counseling became increasingly formalized, with physicians and attendants guiding patients through structured routines.

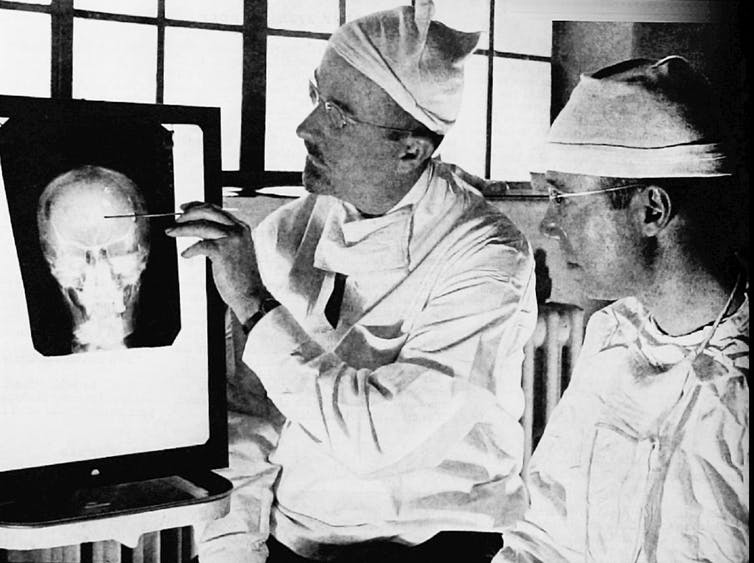

Neurology and Somatic Therapies

The nineteenth century also brought somatic experimentation. Electrotherapy, hydrotherapy, and sedative drugs were employed in asylums, often with mixed outcomes.12 The rise of neurology linked mental illness to brain pathology, fostering optimism that technological interventions could “cure” madness. Phrenology, though discredited, reflected a cultural desire to map mental states onto cranial forms.13

Freud and the Birth of Psychoanalysis

Sigmund Freud revolutionized therapy by theorizing unconscious drives and developing psychoanalysis, rooted in free association, dream interpretation, and transference.14 Though controversial, Freud institutionalized the “talking cure” as a professional practice, giving rise to counseling psychology and later schools of psychotherapy. Here, the “technology” was symbolic (the couch, the analytic framework) as much as material.

Modern and Contemporary Era

Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry

The mid-twentieth century marked a watershed with the development of psychopharmaceuticals: chlorpromazine (antipsychotic), imipramine (antidepressant), lithium (mood stabilizer).15 These drugs transformed asylum populations, contributing to deinstitutionalization. Technologies such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and psychosurgery (lobotomy) reflected both the promise and peril of biomedical approaches.16

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies and Counseling Models

Meanwhile, psychological paradigms diversified. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), pioneered by Aaron Beck, emphasized structured interventions to reshape maladaptive thought patterns.17 Counseling psychology expanded to schools, workplaces, and community centers, integrating talk therapy with practical guidance. Marriage counseling, group therapy, and humanistic approaches (Carl Rogers, Abraham Maslow) emphasized empathy, authenticity, and growth.

Digital and Technological Frontiers

The twenty-first century has seen the rise of teletherapy, mental health apps, and AI-driven chatbots offering counseling support.18 Neuroimaging technologies such as fMRI provide new insights into the biological correlates of depression, anxiety, and trauma. Virtual reality is being tested for exposure therapy, particularly for PTSD.19 These innovations continue the long tradition of embedding mental health care in technological change.

Conclusion

The arc of mental health treatment demonstrates both continuity and transformation. Ancient rituals and philosophical dialogues prefigure modern therapies, while technologies from trephines to smartphones mediate the therapeutic encounter. Across time, the balance between compassion and coercion, healing and control, has shaped how societies respond to psychic distress. What remains constant is the recognition, however framed, that human beings require care for the mind as much as for the body. The history of mental health is thus a history of culture, science, and humanity itself.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Jean Bottéro, Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 155–158.

- John F. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine (London: British Museum Press, 1996), 124–126.

- Vivian Nutton, Ancient Medicine (London: Routledge, 2013), 159–164.

- Martha C. Nussbaum, The Therapy of Desire: Theory and Practice in Hellenistic Ethics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 28–32.

- Galen, On the Causes of Symptoms, trans. Ian Johnston (London: Routledge, 2011), 47–49.

- Dominik Wujastyk, The Roots of Ayurveda (London: Penguin, 2003), 88–92.

- Roy Porter, Madness: A Brief History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 54–59.

- Avicenna, Canon of Medicine, trans. Laleh Bakhtiar (Chicago: Great Books of the Islamic World, 1999), 321–326.

- Jonathan Andrews, Bedlam: London and Its Mad (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 113–118.

- Johann Weyer, On the Tricks of Demons, trans. George Mora (Binghamton: Medieval & Renaissance Texts, 1991), 201–205.

- Philippe Pinel, Traité médico-philosophique sur l’aliénation mentale (Paris: Richard, Caille et Ravier, 1801), 67–72.

- Edward Shorter, A History of Psychiatry (New York: Wiley, 1998), 118–124.

- John van Wyhe, Phrenology and the Origins of Victorian Scientific Naturalism (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), 43–47.

- Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, trans. James Strachey (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 112–116.

- David Healy, The Antidepressant Era (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 45–50.

- Jack Pressman, Last Resort: Psychosurgery and the Limits of Medicine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 198–203.

- Aaron T. Beck, Cognitive Therapy of Depression (New York: Guilford Press, 1979), 34–39.

- John Torou, et.al., “The Evolving Field of Digital Mental Health: Current Evidence and Implementation Issues for Smartphone Apps, Generative Artificial Intelligence, and Virtual Reality,” World Psychiatry 15, no. 24 (2025): 162.

- Melanie Smith, “Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for PTSD,” PsyTechVR (March 21, 2025): https://psytechvr.com/vr-exposure-therapy-ptsd.

Bibliography

- Andrews, Jonathan. Bedlam: London and Its Mad. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

- Avicenna. Canon of Medicine. Translated by Laleh Bakhtiar. Chicago: Great Books of the Islamic World, 1999.

- Beck, Aaron T. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press, 1979.

- Bottéro, Jean. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

- Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams. Translated by James Strachey. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

- Galen. On the Causes of Symptoms. Translated by Ian Johnston. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Healy, David. The Antidepressant Era. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Nunn, John F. Ancient Egyptian Medicine. London: British Museum Press, 1996.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. The Therapy of Desire: Theory and Practice in Hellenistic Ethics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Pinel, Philippe. Traité médico-philosophique sur l’aliénation mentale. Paris: Richard, Caille et Ravier, 1801.

- Porter, Roy. Madness: A Brief History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Pressman, Jack. Last Resort: Psychosurgery and the Limits of Medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Shorter, Edward. A History of Psychiatry. New York: Wiley, 1998.

- Smith, Melanie. “Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for PTSD.” PsyTechVR (March 21, 2025): https://psytechvr.com/vr-exposure-therapy-ptsd.

- Torous, John, et.al. “The Evolving Field of Digital Mental Health: Current Evidence and Implementation Issues for Smartphone Apps, Generative Artificial Intelligence, and Virtual Reality.” World Psychiatry 15, no. 24 (2025): 156-174.

- van Wyhe, John. Phrenology and the Origins of Victorian Scientific Naturalism. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

- Weyer, Johann. On the Tricks of Demons. Translated by George Mora. Binghamton: Medieval & Renaissance Texts, 1991.

- Wujastyk, Dominik. The Roots of Ayurveda. London: Penguin, 2003.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.