To write the history of the middle class is to write the history of modernity, not from above or below, but from the uneasy, imaginative, self-conscious space in between.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Between Privilege and Proletariat

The middle class is a curious invention. It is not merely a demographic category or an economic stratum. It is a political aspiration, a moral self-image, and a cultural construct that has reinvented itself across centuries of upheaval. Unlike aristocracies built on blood and land, or proletariats born in the furnace of labor, the middle class is a fluid artifact of historical contingencies, emerging, expanding, and transforming as capitalism reconfigured the boundaries of wealth, education, and social legitimacy.

This essay traces the historical evolution of the middle class from its late medieval roots to the complexities of the twenty-first century. It follows the formation of the bourgeoisie in urban Europe, examines the class’s transformation during the Renaissance and early capitalism, charts its rise as a political force in the Enlightenment, observes its redefinition during the Industrial Revolution, and considers its globalized ambiguities in the modern world. At each stage, the middle class has been both subject and agent, shaped by structural forces yet also shaping the world it inhabits.

To study the middle class is not simply to map income brackets or occupational trends. It is to understand how societies negotiate legitimacy, how states cultivate allies, and how individuals come to locate themselves within shifting economic hierarchies and moral orders.

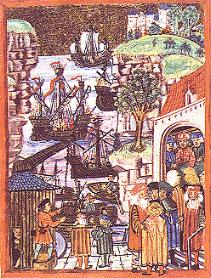

The Bourgeoisie Is Born: Urban Space and Economic Identity in the Late Medieval Period

The origins of the European middle class lie in the transformation of the medieval city. As feudal lords extracted tribute from rural peasants and kings struggled to centralize authority, urban centers emerged as nodes of trade, administration, and proto-capitalist exchange. The bourg, or fortified town, gave rise to a distinct population of artisans, merchants, and guild members, people who neither toiled the land nor bore noble titles.1

These burghers, or bourgeois, were defined not by blood or landownership but by occupation and economic function. In northern Italy, the Low Countries, and the German city-states, wealthy merchant families gained increasing autonomy, sometimes challenging episcopal or feudal authority. In the Hanseatic League and the banking houses of Florence and Bruges, a proto-bourgeois identity took form, organized around credit, reputation, and contractual obligation rather than feudal allegiance.2

Guilds played a pivotal role in shaping this identity. They regulated training, monitored production, and enforced moral codes. In doing so, they asserted not only economic power but also civic authority. The middle class, in its embryonic form, was already a legal actor – claiming rights, defending privileges, and organizing urban governance.3

The late medieval bourgeoisie remained politically subordinate and culturally ambivalent. Its wealth often outpaced its status. Yet by the fourteenth century, the outlines of a third estate were taking shape: neither noble nor peasant, but indispensable.

The Renaissance and Early Capitalism: Literacy, Luxury, and the Class of Calculation

The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries witnessed the intensification of commercial capitalism, especially in maritime republics and emerging Atlantic economies. The middle class became more stratified, with wealthy merchant capitalists differentiating themselves from artisans and shopkeepers. The expansion of bookkeeping, double-entry accounting, and business correspondence created a new literate elite whose daily work depended on calculation, literacy, and trust.4

This period also saw the birth of the “civic humanist” ideal, particularly in Italian city-states, where education, rhetoric, and moral philosophy were adopted by mercantile elites as a way to legitimize their social ascent. The virtuous citizen replaced the feudal warrior as a model of prestige. In cities like Venice, Florence, and Antwerp, the home became a site of aesthetic cultivation and moral order. Art patronage, vernacular literacy, and etiquette manuals reflected a class invested not only in wealth but in refinement.5

At the same time, early capitalism exposed internal contradictions. Profit and piety collided in debates over usury. Markets expanded, but labor remained tied to rigid apprenticeship systems. The printing press democratized knowledge, but also seeded social anxiety about disorder and class mobility. The middle class gained cultural confidence but remained vulnerable to aristocratic disdain and plebeian resentment.

The Enlightenment and Eighteenth Century: The Middle Class as Political Force

The eighteenth century marked a decisive turn: the middle class became not only an economic actor but a political one. Philosophers from Locke to Rousseau conceptualized society in ways that privileged the propertied, literate citizen, figures who, not coincidentally, mirrored the aspirations of the bourgeois intelligentsia. The Enlightenment exalted reason, merit, and civic virtue. These were the currencies of a class that gained strength not through lineage but through education, diligence, and thrift.6

In France, the tiers état (third estate) of lawyers, clerks, and professionals emerged as a coherent class before the Revolution. Their exclusion from political power, despite their central role in administration and commerce, became a foundational grievance. The Cahiers de Doléances of 1789 articulate a middle-class voice calling for legal equality, tax reform, and civic recognition.7

In Britain and its colonies, the growing influence of the professional and mercantile classes reshaped parliamentary politics and fueled debates about representation, taxation, and rights. The American Revolution itself can be understood, in part, as a bourgeois assertion against metropolitan economic control and aristocratic disdain.8

The Enlightenment reconfigured class discourse. Nobility was no longer self-evidently legitimate. Wealth was no longer suspect. The middle class positioned itself as the rational core of the nation: neither parasitic nor rebellious, but stable, productive, and modern.

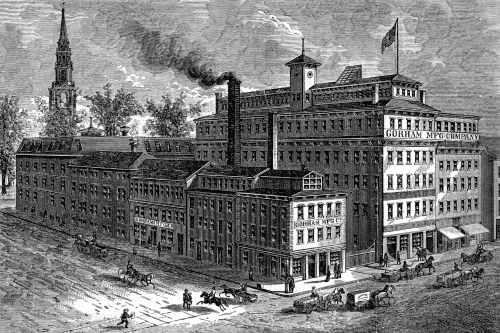

The Industrial Revolution: Factories, Friction, and the Rise of the “Modern” Middle Class

With industrial capitalism came the most visible expansion, and stratification, of the middle class. Managers, engineers, accountants, teachers, and bureaucrats formed a new social stratum between capital and labor. They lived in suburbs, read newspapers, joined voluntary societies, and increasingly defined national culture. The “modern” middle class was not defined solely by ownership, but by control of knowledge, systems, and labor.9

At the same time, the middle class differentiated itself from both aristocratic leisure and proletarian toil. It championed moral discipline, domesticity, and respectability. The Victorian ideal of the self-made man, the virtuous housewife, and the obedient child became a template for class identity.10

This period also witnessed the institutional consolidation of middle-class values. Public education systems were designed to inculcate punctuality, literacy, and deference. Religious movements, particularly evangelical Protestantism, found fertile ground in the bourgeois psyche. Reform campaigns, from temperance to poor law reform, sought to impose middle-class norms on the working poor.

Yet contradictions abounded. Industrial pollution, slums, and labor unrest undermined the moral order the middle class championed. The Chartist movement and revolutions of 1848 exposed tensions between political liberalism and economic hierarchy. The middle class was caught between its alliance with capital and its fear of proletarian revolt. Its identity became as much about containment as aspiration.

Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries: Globalization, Anxiety, and the Ambiguous Core

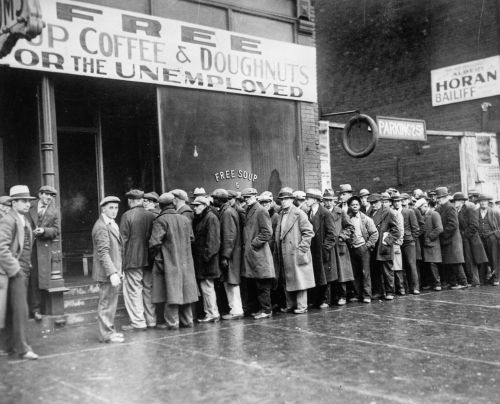

Mass Consumption and the Democratic Middle

In the twentieth century, the middle class became the normative center of many industrial societies. Mass production and mass consumption created conditions in which clerks, teachers, technicians, and low-level managers could own homes, access higher education, and participate in political life. The New Deal, European welfare states, and postwar economic booms all contributed to the consolidation of a broad middle class that imagined itself as the backbone of the nation.11

Consumer goods, once luxuries, became markers of status and identity. Automobiles, suburban homes, and televisions were no longer the prerogatives of the wealthy. The middle class was rebranded as inclusive, aspirational, and patriotic. Yet this expansion depended on stable employment, state policy, and global inequality.

Global Shifts and the Fragile Present

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the middle class has undergone fragmentation. Deindustrialization, wage stagnation, and the rise of precarious work have eroded traditional notions of security. Meanwhile, a new global middle class has emerged (particularly in China, India, and parts of Latin America) transforming consumption patterns and economic influence.

Digitization, automation, and the gig economy have decoupled middle-class status from traditional career paths. In Western societies, rising housing costs, student debt, and healthcare insecurity have fueled a sense of betrayal. Political movements on both left and right have tapped into middle-class resentment, often turning it against migrants, elites, or international institutions.

Today, the middle class remains central to political discourse but is increasingly difficult to define. It is more a contested narrative than a coherent category. It embodies both promise and anxiety, cohesion and fragmentation. It remains, as ever, the class of transition.

Conclusion: A Class Without a Final Form

The middle class has no single origin and no fixed destiny. It has meant many things: merchant, citizen, bureaucrat, consumer, voter. It has been hailed as the bearer of democracy, the guarantor of stability, the custodian of reason. It has also been mocked as conformist, parochial, and complicit.

What unites its history is its relationship to power. The middle class has always existed in tension: too powerful to ignore, too fluid to control, too aspirational to satisfy. Its rise marked the erosion of fixed hierarchies. Its evolution mirrors the changing architecture of capitalism itself.

To write the history of the middle class is to write the history of modernity, not from above or below, but from the uneasy, imaginative, self-conscious space in between.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Henri Pirenne, Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade, trans. Frank D. Halsey (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1925), 77–89.

- Peter Spufford, Power and Profit: The Merchant in Medieval Europe (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2002), 34–41.

- Martha C. Howell, Commerce before Capitalism in Europe, 1300–1600 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 121–145.

- Jacob Soll, The Reckoning: Financial Accountability and the Rise and Fall of Nations (New York: Basic Books, 2014), 58–64.

- Lauro Martines, Power and Imagination: City-States in Renaissance Italy (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), 203–217.

- John Locke, Two Treatises of Government, ed. Peter Laslett (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 287–291.

- William Doyle, Origins of the French Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), 92–99.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1993), 151–178.

- Harold Perkin, The Origins of Modern English Society, 1780–1880 (London: Routledge, 2002), 45–62.

- Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall, Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780–1850 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 87–103.

- C. Wright Mills, White Collar: The American Middle Classes (New York: Oxford University Press, 1951), 13–21.

Bibliography

- Davidoff, Leonore, and Catherine Hall. Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780–1850. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Doyle, William. Origins of the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Hall, Catherine, and Leonore Davidoff. Family Fortunes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Howell, Martha C. Commerce before Capitalism in Europe, 1300–1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Locke, John. Two Treatises of Government. Edited by Peter Laslett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Martines, Lauro. Power and Imagination: City-States in Renaissance Italy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988.

- Mills, C. Wright. White Collar: The American Middle Classes. New York: Oxford University Press, 1951.

- Perkin, Harold. The Origins of Modern English Society, 1780–1880. London: Routledge, 2002.

- Pirenne, Henri. Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade. Translated by Frank D. Halsey. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1925.

- Soll, Jacob. The Reckoning: Financial Accountability and the Rise and Fall of Nations. New York: Basic Books, 2014.

- Spufford, Peter. Power and Profit: The Merchant in Medieval Europe. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2002.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage, 1993.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.24.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.