The medieval experience warns of continuity. The same mechanisms (demonization, dehumanization, apocalyptic urgency) reappear in modern contexts of extremism and authoritarianism.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The medieval world was shaped not only by swords and cathedrals but also by words that cut as deeply as steel. Preachers, monarchs, and chroniclers alike deployed violent rhetoric to define enemies, inspire followers, and justify coercion. In an era when literacy was uneven but orality powerful, the spoken sermon, the shouted battle cry, and the carefully crafted polemic carried profound weight. Such rhetoric was not ornamental: it functioned as an instrument of mobilization and legitimation, often preceding or accompanying physical violence. When Pope Urban II declared at Clermont in 1095 that God willed the crusade, he offered not a policy proposal but a divine imperative that reoriented Christian society toward holy war.1

Medieval thinkers themselves recognized the dangerous potency of speech. Augustine warned that words could inflame passions more violently than deeds,2 while canonists and theologians wrestled with whether rhetoric itself could constitute heresy, blasphemy, or treason. The language of poison, contagion, and infestation (applied to heretics, Jews, and Muslims) did not simply describe: it dehumanized, preparing populations for exclusion or extermination.3 From the burning of Cathars in southern France to pogroms following accusations of ritual murder, the leap from word to deed was often perilously short.

What follows examines violent rhetoric in the medieval world as both a cultural artifact and a catalyst for action. It argues that rhetorical violence was not merely reflective of social tensions but constitutive of them, shaping identities, legitimizing authority, and normalizing bloodshed. By tracing its deployment across political propaganda, crusading sermons, inquisitorial discourse, and popular uprisings, we can see how language functioned as a weapon no less destructive than the sword and sometimes far more enduring.

Conceptual Foundations of Medieval Violent Rhetoric

The potency of violent rhetoric in the medieval world cannot be understood without recognizing its deep roots in biblical and patristic traditions. Scripture itself was rife with martial metaphors: the prophets spoke of God’s wrath as a consuming fire, while the Psalms were filled with images of enemies dashed to pieces or blotted from the book of life.4 Early Christian writers inherited this idiom, yet reinterpreted it for a church navigating between persecution and empire. Augustine, in his City of God, employed stark language to contrast the civitas Dei with the civitas terrena, framing worldly powers as corrupted and violent by nature.5 Such formulations offered later medieval preachers and polemicists a ready arsenal of words that could transform opponents into embodiments of divine enemies.

At the same time, medieval culture was acutely aware of the power of speech itself. Rhetoric was not conceived as neutral ornament but as a moral and spiritual force. Isidore of Seville, whose Etymologiae circulated widely, linked language to the very ordering of the cosmos, warning that words could deceive, inflame, and destroy.6 The scholastic revival of Aristotle in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries added further nuance: the Rhetoric taught that persuasion worked by stirring the passions, and passions once roused could topple reason. Thomas Aquinas, reading both Aristotle and Augustine, acknowledged that speech could lead souls either to truth or to sin, depending on its use.7 This fusion of classical and Christian thought produced a medieval consensus that violent speech was not trivial but spiritually dangerous.

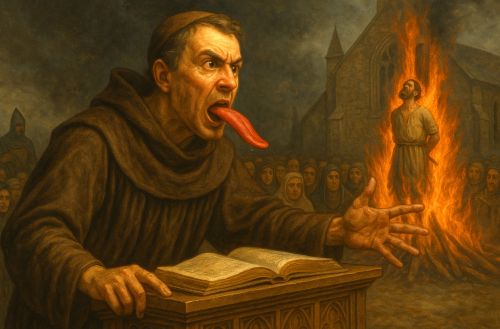

The pulpit, above all, magnified rhetoric’s reach. Preaching was one of the central performative acts of medieval religious life, and sermons were expected not merely to instruct but to move. The ars praedicandi manuals that proliferated from the thirteenth century emphasized affective appeals: stories, images, and metaphors designed to touch the heart.8 When preachers described heresy as a plague or Jews as devourers of Christian children, their words were not intended as abstract theology. They were crafted to shock, to unsettle, and to mobilize listeners into action. In such moments, rhetoric blurred into ritual, transforming crowds into communities bound by shared fear and fury.

Thus, the conceptual foundation of medieval violent rhetoric lay in a double inheritance: the biblical-patristic tradition of sharp verbal dichotomies, and the scholastic recognition of rhetoric’s power over the passions. Together, they ensured that words could never be dismissed as ephemeral. They were themselves acts, capable of sanctifying war, justifying persecution, and eroding the boundaries between speech and bloodshed.

Political Rhetoric and the Legitimation of Violence

If rhetoric carried divine weight in the pulpit, it carried existential force in the political sphere. Medieval rulers, lacking modern bureaucratic apparatuses, relied heavily on speech and symbolic gesture to maintain authority. Declarations of loyalty or treason, accusations of tyranny, or proclamations of just war all hinged on rhetorical framing. To call one’s rival a “tyrant” was not merely an insult; it stripped him of legitimacy and opened the door to rebellion.9 Such terms echoed classical traditions of political invective, yet in the medieval world they became performative utterances that shaped both law and violence.

The Carolingian dynasty offers a telling case. Einhard’s Life of Charlemagne portrays the king as defender of Christendom, contrasting him with pagan enemies who were described in terms of barbarism and savagery.10 When later Carolingians faced internal rebellion, their propaganda framed opponents as betrayers not just of the crown but of God. To resist the king was to resist divine order itself, a rhetorical move that justified brutal suppression of insurrections.11 In England, similar strategies were deployed: chroniclers of the twelfth-century civil war between Stephen and Matilda cast rivals as violators of oaths, their words dripping with connotations of perjury and moral rot.

By the later Middle Ages, such rhetoric became increasingly juridical. The concept of crimen laesae maiestatis (crime of injured majesty) expanded from the Roman idea of treason against the emperor to include verbal offenses against the sovereign.12 A whispered insult could, in theory, be prosecuted as a violent attack on the body politic. Kings and princes thus wielded rhetoric as both sword and shield, deploying invective against rivals while criminalizing hostile speech against themselves. Political speech became a battlefield where words could kill reputations, incite executions, and destabilize entire realms.

The power of political rhetoric, then, was its capacity to transform dissent into treason and rivalry into rebellion. By casting opposition in terms of moral corruption or cosmic disorder, rulers legitimized not only their authority but also the violence required to defend it. In such contexts, speech and bloodshed were not separate domains but mutually reinforcing instruments of medieval statecraft.

Ecclesiastical Rhetoric and Crusading Mobilization

No arena better demonstrates the lethal fusion of words and action in the medieval world than the preaching of the crusades. When Pope Urban II stood at Clermont in 1095, his call was not a dry policy directive but a rhetorical performance. Chroniclers differ in their accounts, but all agree that he framed the expedition as a divine imperative, punctuated by the electrifying cry Deus vult! (“God wills it!”).13 This phrase did more than sanction war: it created a new identity, transforming ordinary Christians into soldiers of Christ, and inscribing violence with sacral legitimacy.

The rhetoric of the crusade pulpit trafficked heavily in demonization. Muslims were depicted as “unclean dogs,” “pagans,” and “servants of Satan.”14 Such imagery was not intended as description but as provocation: by presenting the enemy as monstrous, preachers reduced the moral cost of killing. The crusading sermon thus acted as a bridge between theological abstraction and martial practice, turning soldiers’ swords into extensions of divine will.

This rhetoric proved adaptable across contexts. During the Albigensian Crusade (1209–29), directed not against Muslims but against fellow Christians in southern France, papal legates employed the same tropes of pollution and contagion. Heretics were labeled “worse than Saracens,” carriers of spiritual disease who threatened to rot Christendom from within.15 The infamous command attributed to Abbot Arnaud Amalric at Béziers, “Kill them all; God will know his own,” mcaptures the logic of this discourse. Whether or not he actually spoke the words, their circulation illustrates how easily rhetoric could collapse distinctions between guilt and innocence, preparing the way for indiscriminate slaughter.

By the thirteenth century, the rhetorical machinery of crusading had become institutionalized. Papal bulls adopted a formulaic language of exhortation and demonization; indulgences were packaged with fiery appeals; preaching campaigns moved with military precision.16 Violence was no longer justified on pragmatic grounds but demanded by rhetoric that cast Christendom in perpetual peril. Through repetition, crusading rhetoric normalized holy war, embedding it in the spiritual imagination of Europe.

Thus, ecclesiastical rhetoric did not merely authorize crusading violence; it made it thinkable, desirable, and sacred. Without the incendiary sermons and papal proclamations that framed crusade as God’s command, the mobilization of tens of thousands across centuries would have been unthinkable. Words, in this sense, were the first crusading weapons unsheathed.

Heresy, Inquisition, and Internal Enemies

If crusading rhetoric projected enemies outward, inquisitorial rhetoric turned inward, casting suspicion upon neighbors, fellow Christians, even family members. From the twelfth century onward, heresy was increasingly framed as an existential threat, not merely a theological error. Language here was crucial: heretics were not depicted as misguided but as diseased, verminous, or poisonous. Inquisitorial manuals, such as Bernard Gui’s Practica Inquisitionis, described heresy as an “infection” spreading silently through Christendom.17 Such metaphors prepared audiences to see eradication (through imprisonment, torture, or execution) as a form of spiritual hygiene.

The Cathars of Languedoc provide perhaps the starkest example. Chroniclers and papal legates alike labeled them “sons of Belial,” their teachings “venomous serpents’ tongues” that corrupted the faithful.18 These words were not neutral descriptors but weapons of classification: they recast religious dissenters as ontological enemies. The burning of Cathars was justified not simply by legal decree but by rhetorical transformation. The people destroyed were no longer fellow Christians but agents of decay.

What made inquisitorial rhetoric distinctive was its systematic codification. Unlike the episodic sermons of crusade preaching, inquisitorial discourse was preserved in depositions, handbooks, and trial records. These texts standardized the language of danger, repeating metaphors of rot and contagion until they became self-evident truths.19 In doing so, they did not merely reflect social paranoia but actively created it. Entire communities learned to interpret dissent through the lens of contamination, a frame that legitimized both denunciation and repression.

Yet inquisitorial rhetoric was not always effective in silencing resistance. In some cases, the violent language of exclusion hardened the resolve of dissenting groups, pushing them into underground networks or martyrdom.20 Here, the consequences of violent rhetoric proved paradoxical: designed to extinguish heterodoxy, it sometimes gave it new vitality by sharpening the sense of embattled identity among persecuted groups.

Inquisitorial rhetoric thus exemplifies the medieval blurring of speech and action. By constructing heresy as an invisible plague, it expanded suspicion indefinitely, justifying perpetual surveillance and repeated cycles of violence. In this way, words not only preceded violence but sustained it, ensuring that Christendom remained locked in a struggle against enemies it could never quite eradicate.

Anti-Jewish and Anti-Muslim Rhetoric

Few groups were more consistently targeted by violent medieval rhetoric than Jews and Muslims. Both were constructed not merely as religious others but as existential threats to Christendom’s stability. Words became the first blows: accusations, polemics, and slanders that eroded coexistence and justified waves of persecution.

Anti-Jewish rhetoric drew heavily on biblical typologies. Preachers depicted Jews as the “Christ-killers,” eternally guilty for the crucifixion.21 The persistence of Jewish communities in Christian lands was framed not as a fact of social diversity but as a divine test, their continued presence proof of obstinate blindness.22 More insidious still were rhetorical inventions such as the blood libel. Narratives of Jews murdering Christian children for ritual purposes circulated from Norwich in 1144 onward,23 creating an imaginative landscape where Jewish neighbors became monstrous predators. These accusations were often followed by pogroms, expulsions, or forced conversions, direct consequences of words made flesh.

The language deployed against Muslims operated differently but with no less intensity. In crusading and reconquest contexts, Muslims were portrayed as idolaters, servants of demons, or corrupters of sacred places.24 Polemicists like Peter the Venerable wrote tracts that described Islam as a heresy spawned by deceit, with Muhammad cast as a false prophet inspired by the devil.25 Such rhetoric stripped Islam of legitimacy and placed it within a Christian framework of error to be corrected or crushed. On the Iberian Peninsula, where Christians, Muslims, and Jews lived in uneasy proximity, sermons routinely framed Muslims as a fifth column, waiting for the chance to betray Christian rulers.26

The cumulative effect of this rhetoric was to normalize suspicion and hostility. Anti-Jewish sermons often coincided with seasonal feasts such as Easter, when the passion narrative intensified animosity, while anti-Muslim polemics gained traction during crusading calls and moments of political tension. Words here were cyclical weapons, timed to ritual calendars and political needs.

The consequences were devastating. Massacres in the Rhineland during the First Crusade, expulsions from England (1290), France (1306), and Spain (1492), and forced conversions under both Christian and Muslim rulers all reveal how rhetoric prepared the way for coercion.27 Similarly, the rhetoric of reconquest and crusade justified centuries of intermittent warfare across the Mediterranean. In both cases, rhetorical violence blurred the boundary between religious polemic and social policy, embedding prejudice into law and collective memory.

Popular Movements and Violent Speech

Violent rhetoric was not the preserve of popes and kings. It also coursed through the words of wandering preachers, millenarian prophets, and popular leaders who claimed divine sanction for radical upheaval. In these contexts, rhetoric functioned less as polished polemic than as raw incitement, transmitted through rumor, prophecy, and public performance.

The Flagellant movements of the fourteenth century exemplify this dynamic. At a time of plague and social collapse, self-proclaimed prophets interpreted catastrophe as divine punishment and summoned crowds to public penance. Their rhetoric, heavy with apocalyptic imagery, often veered into denunciation of Jews and clergy, whom they cast as responsible for God’s wrath.28 Such words did not remain symbolic. Pogroms frequently followed in the wake of Flagellant processions, demonstrating how millenarian speech could ignite violence at the local level.

Similar patterns can be traced in radical reform movements like the Taborites during the Hussite wars. Their preachers invoked the rhetoric of the Last Days, portraying enemies of their cause as Antichrist’s servants.29 Sermons and songs called not simply for resistance but for purgation, envisioning violence as the cleansing fire that would inaugurate God’s kingdom. Here rhetoric was inseparable from praxis: the words spoken in fields and villages shaped the actions of armed bands who saw themselves as holy warriors.

Even peasant revolts were steeped in violent language. The English Rising of 1381, for instance, was galvanized by sermons that denounced lords as “traitors to the commons” and enemies of God’s justice.30 While socioeconomic grievances drove rebellion, rhetoric supplied the moral vocabulary that legitimized violent uprising. Leaders like John Ball, with his famous refrain “When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?” weaponized biblical simplicity into revolutionary critique.31

In each of these cases, violent rhetoric carried special potency because it emerged outside institutional control. Unlike papal bulls or royal decrees, the speech of popular movements relied on immediacy, rumor, and repetition in the streets. Its power lay in its volatility: unpredictable, contagious, and difficult to suppress. Words in these contexts were not carefully archived but lived as oral fire: quick to flare, quick to consume.

Consequences of Violent Rhetoric

The immediate consequence of violent rhetoric in the medieval world was bloodshed. The massacres of Jews in the Rhineland during the First Crusade, the burning of Cathars in southern France, and the repeated pogroms that accompanied plague years all attest to the catalytic force of incendiary words.32 These were not spontaneous eruptions of violence but events preceded by sermons, proclamations, and rumors that framed targets as subhuman, diseased, or demonic. Speech prepared the ground upon which swords and torches were later deployed.

Beyond the physical toll, violent rhetoric reshaped the psychological landscape of medieval society. It normalized fear as a communal glue. Jews were portrayed as perpetual conspirators, Muslims as enemies lurking at Christendom’s borders, heretics as contagious parasites.33 The ubiquity of these images fostered a climate of suspicion where difference itself became a potential danger. In this sense, rhetoric did not simply precede violence; it ensured that entire populations lived within a mental architecture of hostility.

There were also institutional consequences. The growing criminalization of words, from charges of heresy to accusations of treason, demonstrates how rhetoric itself became a legal battlefield.34 Medieval courts recognized that speech could fracture communities as effectively as armed rebellion. This recognition led to the surveillance of sermons, the licensing of preachers, and the codification of censorship. By the late Middle Ages, the apparatus of control over rhetoric, epitomized by inquisitorial tribunals and royal courts, had become a permanent feature of governance.

Finally, violent rhetoric had a lasting cultural legacy. Once words of demonization entered chronicles, hagiographies, and liturgy, they were transmitted to future generations.35 This textual afterlife gave permanence to what may have begun as ephemeral speech, embedding hostility into the memory of Christendom. The durability of these texts ensured that prejudices survived long after the events that provoked them, contributing to enduring patterns of exclusion and intolerance.

The consequences of violent rhetoric in the medieval world were manifold: immediate acts of violence, long-term psychological conditioning, institutionalized repression, and cultural memory. Together, they reveal that rhetoric was not a secondary phenomenon but a central engine of medieval conflict, shaping both the imagination and the reality of violence.

Historiography and Modern Resonances

Modern historiography has wrestled with the problem of violent rhetoric in the medieval world: was it primarily a mirror of existing tensions, or did it actively create the violence it accompanied? Older generations of scholars, influenced by institutional history, tended to see rhetoric as epiphenomenal, mere propaganda that reflected political or religious conflicts already underway.36 More recent approaches, drawing from cultural history and discourse analysis, emphasize the constitutive power of language. In this view, rhetoric was not a byproduct but a catalyst: it shaped categories of identity, defined enemies, and structured the very possibilities of action.37

Debates about crusading rhetoric illustrate this historiographical shift. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century historians often treated papal speeches at Clermont as colorful flourishes overlaying material motives such as land hunger or aristocratic ambition.38 Contemporary scholars, however, stress that without the rhetoric of sanctified violence, there would have been no ideological framework for mass mobilization.39 The cry Deus vult was not a reflection of latent zeal but a performative utterance that created a new religious and political reality.

Similarly, the study of anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim polemics has shifted from economic and political explanations to an appreciation of the rhetorical imagination. Gavin Langmuir famously argued that medieval anti-Judaism was not merely social tension expressed in religious terms but the elaboration of “chimerical accusations,” linguistic constructs that redefined Jews as inherently malevolent.40 Scholars of interreligious relations now attend to the ways such rhetoric created mental worlds in which violence became plausible, even necessary.

These historiographical developments resonate far beyond medieval studies. Historians and political theorists alike note continuities between medieval violent rhetoric and modern forms of ideological speech. The demonization of minorities, the framing of political rivals as traitors, and the invocation of divine or national destiny recur in contexts ranging from the French Revolution to twentieth-century fascism.41 In recent years, scholars of political communication have even cited medieval polemics as an early form of “dehumanizing discourse,” linking them to the rhetorical strategies that preceded genocides in the modern era.42

The medieval past thus offers not only a field for historical inquiry but also a cautionary mirror. Its sermons, chronicles, and polemics remind us that words are never inert. They can summon armies, justify exclusions, and carve enemies into the social body. Recognizing the active role of rhetoric in shaping violence, then and now, remains one of the most pressing tasks for historians.

Conclusion

This has traced the tangled relationship between words and violence in the medieval world. From papal bulls and crusading sermons to inquisitorial manuals and peasant proclamations, rhetoric emerged not as ornament but as weapon. It defined enemies, legitimized coercion, and prepared audiences for bloodshed. Medieval thinkers themselves understood its potency: Augustine warned of passions inflamed by speech, Aquinas recognized the moral danger of words that led to sin, and inquisitors codified language that transformed dissent into contagion. Rhetoric, in this sense, was never ancillary. It was constitutive.

The consequences were profound. Rhetorical violence generated real violence: pogroms, crusades, burnings, and wars justified by words that dehumanized their targets. It reshaped mental landscapes, teaching communities to perceive outsiders as perpetual threats. It was institutionalized in law, where speech became criminalized as heresy or treason. And it endured in cultural memory, transmitted through chronicles and liturgies that ensured hostility lived on long after the events themselves.

Historians now recognize that violent rhetoric did more than reflect tensions; it created them, channeling fear, sanctifying aggression, and hardening boundaries between “us” and “them.” In doing so, it reminds us that the medieval tongue was not benign but edged, a sword sharpened by scripture, scholastic logic, and political need. To study its effects is to confront the fragility of words and the dangers of their misuse.

The medieval experience also warns of continuity. The same mechanisms (demonization, dehumanization, apocalyptic urgency) reappear in modern contexts of extremism and authoritarianism. Recognizing their medieval genealogy underscores an enduring truth: that rhetoric can mobilize, legitimize, and normalize violence with a force as destructive as any army. In this light, the medieval world offers not only a subject for historical inquiry but also a stark lesson in the peril of dismissing words as harmless.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Robert Somerville, Pope Urban II’s Council of Clermont (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 72–75.

- Augustine, De Doctrina Christiana, trans. R.P.H. Green (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), II.7.

- Jeremy Cohen, Living Letters of the Law: Ideas of the Jew in Medieval Christianity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 145–49.

- Psalms 2:9; 69:28 (Vulgate numbering).

- Augustine, The City of God against the Pagans, trans. R.W. Dyson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), XIX.12.

- Isidore of Seville, Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, trans. Stephen A. Barney et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), I.29.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II–II, q. 72, a. 1.

- Siegfried Wenzel, The Art of Preaching: Five Medieval Texts and Translations (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2013), 3–7.

- Cary J. Nederman, Lineages of European Political Thought: Explorations along the Medieval/Modern Divide from John of Salisbury to Hegel (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2009), 34–36.

- Einhard, Two Lives of Charlemagne, trans. Lewis Thorpe (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969), 58–61.

- Rosamond McKitterick, The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751–987 (London: Longman, 1983), 187–90.

- J.H. Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 4th ed. (London: Butterworths, 2002), 43–45.

- Somerville, Pope Urban II’s Council of Clermont, 83–87.

- Paul Chevedden, “The Islamic View and the Christian View of the Crusades: A New Synthesis,” History 93, no. 310 (2008): 182–84.

- Mark Gregory Pegg, A Most Holy War: The Albigensian Crusade and the Battle for Christendom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 74–76.

- Christopher Tyerman, The Invention of the Crusades (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998), 57–61.

- Bernard Gui, Practica Inquisitionis Heretice Pravitatis, ed. Célestin Douais (Paris: Alphonse Picard, 1886), 1.

- Malcolm Lambert, Medieval Heresy: Popular Movements from the Gregorian Reform to the Reformation, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002), 118–22.

- Edward Peters, Inquisition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 64–69.

- Peter Biller, “The Waldenses 1170–1530: Between a Religious Order and a Church,” in Medieval Christianity in Practice, ed. Miri Rubin (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), 197–99.

- Jeremy Cohen, Christ Killers: The Jews and the Passion from the Bible to the Big Screen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 33–37.

- Gavin Langmuir, Toward a Definition of Antisemitism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 263–65.

- Miri Rubin, Gentile Tales: The Narrative Assault on Late Medieval Jews (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 19–23.

- John Tolan, Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European Imagination (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 46–50.

- Peter the Venerable, Against the Sect of the Saracens, in Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History, ed. David Thomas (Leiden: Brill, 2009), 236–39.

- Olivia Remie Constable, Medieval Iberia: Readings from Christian, Muslim, and Jewish Sources, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997), 289–91.

- Robert Chazan, God, Humanity, and History: The Hebrew First Crusade Narratives (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 82–86.

- Norman Cohn, The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 139–42.

- Howard Kaminsky, A History of the Hussite Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 214–18.

- Steven Justice, Writing and Rebellion: England in 1381 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 55–59.

- R.B. Dobson, The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 (London: Macmillan, 1970), 375–77.

- Robert Chazan, European Jewry and the First Crusade (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 88–93.

- Cohen, Living Letters of the Law, 145–49.

- Baker, English Legal History, 43–45.

- John V. Tolan, Sons of Ishmael: Muslims through European Eyes in the Middle Ages (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008), 211–15.

- Carl Erdmann, The Origin of the Idea of Crusade, trans. Marshall W. Baldwin and Walter Goffart (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977), 23–27.

- Miri Rubin, Corpus Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 11–14.

- Heinrich von Sybel, Geschichte des ersten Kreuzzuges (Düsseldorf: J. Buddeus, 1841), 56–59.

- Jonathan Riley-Smith, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972), 23–28.

- Langmuir, Toward a Definition of Antisemitism, 263–65.

- Robert O. Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 173–76.

- David Livingstone Smith, Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2011), 45–48.

Bibliography

- Augustine. De Doctrina Christiana. Translated by R.P.H. Green. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

- Augustine. The City of God against the Pagans. Translated by R.W. Dyson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Baker, J.H. An Introduction to English Legal History. 4th ed. London: Butterworths, 2002.

- Biller, Peter. “The Waldenses 1170–1530: Between a Religious Order and a Church.” In Medieval Christianity in Practice, edited by Miri Rubin, 195–210. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Chazan, Robert. European Jewry and the First Crusade. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Chazan, Robert. God, Humanity, and History: The Hebrew First Crusade Narratives. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Chevedden, Paul. “The Islamic View and the Christian View of the Crusades: A New Synthesis.” History 93, no. 310 (2008): 181–200.

- Cohen, Jeremy. Christ Killers: The Jews and the Passion from the Bible to the Big Screen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Cohen, Jeremy. Living Letters of the Law: Ideas of the Jew in Medieval Christianity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Cohn, Norman. The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Constable, Olivia Remie. Medieval Iberia: Readings from Christian, Muslim, and Jewish Sources. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997.

- Dobson, R.B. The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. London: Macmillan, 1970.

- Einhard. Two Lives of Charlemagne. Translated by Lewis Thorpe. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969.

- Erdmann, Carl. The Origin of the Idea of Crusade. Translated by Marshall W. Baldwin and Walter Goffart. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

- Gui, Bernard. Practica Inquisitionis Heretice Pravitatis. Edited by Célestin Douais. Paris: Alphonse Picard, 1886.

- Isidore of Seville. Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Translated by Stephen A. Barney et al. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Justice, Steven. Writing and Rebellion: England in 1381. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

- Kaminsky, Howard. A History of the Hussite Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967.

- Lambert, Malcolm. Medieval Heresy: Popular Movements from the Gregorian Reform to the Reformation. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 2002.

- Langmuir, Gavin I. Toward a Definition of Antisemitism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- McKitterick, Rosamond. The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751–987. London: Longman, 1983.

- Nederman, Cary J. Lineages of European Political Thought: Explorations along the Medieval/Modern Divide from John of Salisbury to Hegel. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2009.

- Paxton, Robert O. The Anatomy of Fascism. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

- Pegg, Mark Gregory. A Most Holy War: The Albigensian Crusade and the Battle for Christendom. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Peters, Edward. Inquisition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

- Peter the Venerable. Against the Sect of the Saracens. In Christian-Muslim Relations: A Bibliographical History, edited by David Thomas. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972.

- Rubin, Miri. Corpus Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Rubin, Miri. Gentile Tales: The Narrative Assault on Late Medieval Jews. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Siebel, Heinrich von. Geschichte des ersten Kreuzzuges. Düsseldorf: J. Buddeus, 1841.

- Smith, David Livingstone. Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2011.

- Somerville, Robert. Pope Urban II’s Council of Clermont. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Tolan, John. Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European Imagination. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002.

- Tolan, John V. Sons of Ishmael: Muslims through European Eyes in the Middle Ages. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008.

- Tyerman, Christopher. The Invention of the Crusades. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998.

- Wenzel, Siegfried. The Art of Preaching: Five Medieval Texts and Translations. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2013.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.23.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.