Whether spoken before the gods of Rome, a medieval lord, a constitutional text, or a dictator, the oath is at once legal, religious, and performative. It declares where ultimate loyalty lies.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

From antiquity to the present, the act of swearing an oath has served as a binding hinge between the individual and the political order. Few institutions embody this more powerfully than the military oath. In its ancient Roman form, the sacramentum militare was understood as a sacred pledge of total devotion to the republic and, later, the emperor. The soldier, upon uttering his words, placed his very life in deposit with the state, a religious and juridical act that simultaneously legitimated authority and disciplined obedience.1 With the fragmentation of Roman authority and the emergence of feudal Europe, military allegiance shifted from an impersonal polity to a web of personal bonds. The oath of fealty, performed with clasped hands and kneeling posture, bound vassal to lord in a ritual of fidelity that was at once voluntary and compelled, chosen and constrained.2

The transformation of oaths in the early modern and modern world reflects the larger passage from societies built on personal lordship to states founded on constitutions. In the United States, the oath of military service came to signify loyalty not to a sovereign but to the Constitution itself. “I do solemnly swear that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic” is a formula that enshrines allegiance to an abstract and enduring framework of law rather than to the transient figure of a ruler.3 In this sense, the U.S. oath stands as an expression of civic republicanism, one of the clearest attempts in history to tether the sword to the law.

By stark contrast, the German case in the twentieth century demonstrates the peril of reversing this constitutional principle. Prior to 1934, the Reichswehr swore its oath to the German Constitution and lawful institutions of state. Upon the death of President Hindenburg, however, Adolf Hitler mandated a new formula of allegiance, the Führereid, a personal oath of unconditional fidelity to himself.4 This seemingly technical adjustment in language carried catastrophic consequences, fusing the conscience of the armed forces to the will of a single man and removing the final barrier to dictatorship.

The comparative study of military oaths thus raises urgent historical and philosophical questions. To whom should the soldier be bound, constitution or king, state or dictator, law or person? What are the consequences when the object of allegiance shifts? This essay traces the history of military oaths across three major episodes, the sacramentum of ancient Rome, the fealty oaths of medieval Europe, and the modern transformations culminating in the United States’ constitutional oath and Nazi Germany’s oath to Hitler. In so doing, it argues that the site of oath-taking, whether oriented to abstract principle or to personal sovereignty, reveals the deeper structures of political legitimacy and determines the capacity of institutions either to resist tyranny or to succumb to it.

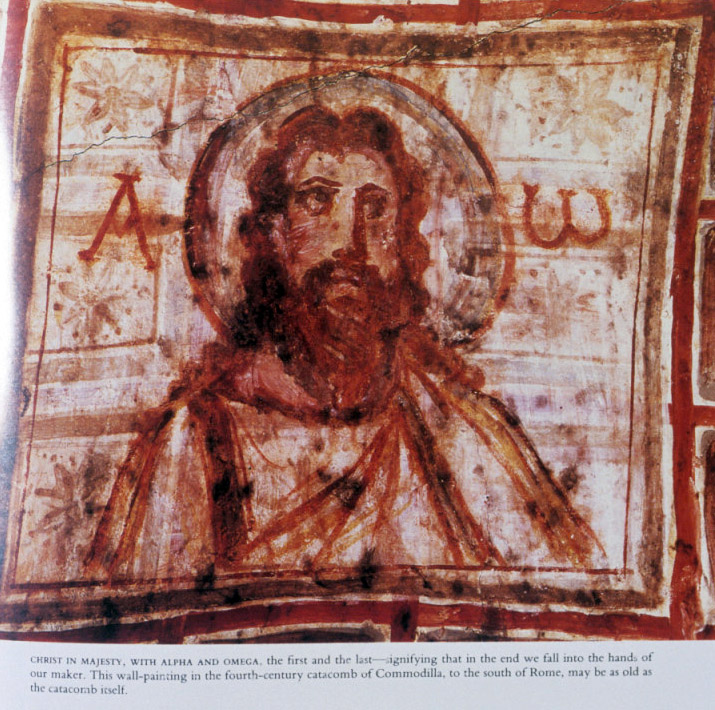

Classical and Late Antiquity: The Roman Sacramentum and Early Christian Tensions

The Roman sacramentum militare was not merely a formal pledge of service; it was a profound act of consecration that fused the civic, legal, and religious spheres of Roman life. Upon enlistment, a recruit declared a binding oath of loyalty to the Senate and people of Rome, and later, under the imperial system, directly to the emperor himself. This was not a matter of simple words. Roman jurists, such as Ulpian, described the sacramentum as a contract of life and death, whereby the soldier pledged himself to endure punishment, even execution, should he break faith.5 It was understood as a sacred deposit, as if the soldier placed his very soul in escrow with the res publica. The oath thus served as a potent mechanism for both personal discipline and collective cohesion, uniting diverse peoples under the single identity of Roman arms.

Renewal of the oath was not a one-time event but a recurring ritual that reinforced the soldier’s bond. In the Republic, it was often sworn at the beginning of the campaigning season; in the Empire, it was repeated annually, woven into military festivals and rites.6 The act carried a religious dimension, invoking the gods as witnesses and enforcers of fidelity. In this sense, the oath was not reducible to law alone; it was an act of piety, binding the legionary’s duty to the divine as much as to the state. The Roman sacramentum therefore encapsulates the classical interpenetration of politics and religion, where the legitimacy of authority was expressed through the language of sacred obligation.

This fusion created deep tensions as Christianity spread within the empire. Early Christian writers wrestled with whether believers could in good conscience swear a pagan oath of blood loyalty to the emperor. For some, like Tertullian, the incompatibility was absolute: a Christian’s oath must be to Christ alone, and participation in idolatrous rites was tantamount to apostasy.7 For others, accommodation was possible, so long as one distinguished between service to the earthly ruler and ultimate fidelity to God. Martyrdom accounts preserve stories of Christian soldiers who refused to renew the sacramentum and were executed as traitors.8 Such episodes reveal the clash between emerging universal religions and the political religion of Rome, and they foreshadow the problem that would recur throughout history: when allegiance to the divine or to conscience collides with sworn loyalty to temporal authority.

By the fourth century, the conversion of Constantine and the Christianization of the empire altered the meaning of the sacramentum. The soldier’s oath was reoriented away from Jupiter and Mars and toward the Christian God, with the emperor now claiming authority as God’s chosen ruler.9 This shift highlights the adaptability of the oath form; though the words changed, the logic of sacred obedience remained. What had once been an act of pagan consecration became a Christian ritual of loyalty, showing that the oath itself was less about theology than about the political need to sacralize obedience. In this way, the Roman sacramentum supplied a template for later feudal and monarchic oaths, a binding act that collapsed law, religion, and loyalty into a single utterance.

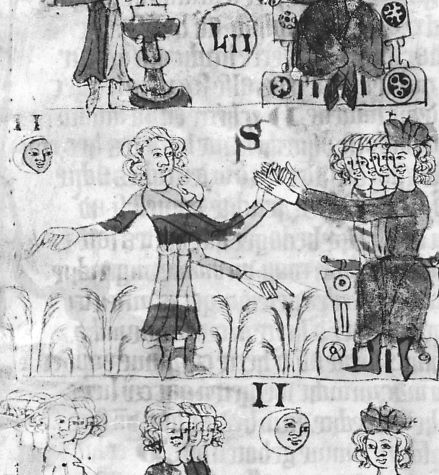

Early and High Medieval Oaths: Fealty, Homage, and the Personal Bond

With the disintegration of Roman imperial authority in the West, the structures of military allegiance underwent profound transformation. No longer bound to an abstract state, warriors and landholders forged bonds of loyalty through personal oaths of fealty and homage. These rituals did more than secure military service; they structured the entire feudal order, translating the Roman sacramentum into a vernacular of kinship, property, and obligation.

The distinction between homage (homagium) and fealty (fidelitas) illustrates the layered nature of medieval allegiance. Homage was an act of personal submission to a single lord, performed in a symbolic ritual of kneeling and clasping hands, reminiscent of the gestures of prayer.10 Fealty, by contrast, could be sworn to multiple lords and was often a more general pledge of loyalty and honesty.11 The performative character of these acts was essential; words alone were insufficient. The ritual bound vassal and lord in a visible and embodied covenant, one that evoked not only legal obligation but affective ties of love and loyalty.

Yet the medieval oath of fealty was never purely voluntary. Scholars debate the extent to which these pledges reflected genuine choice versus coerced necessity.12 The formula of “I become your man” signaled an apparent act of free will, but the surrounding structures of power, economic survival, and martial coercion suggest that vassals often had little true alternative. At the same time, the lord was not free of obligations. In theory, he was bound by reciprocal duties, to protect, to administer justice, and to defend the fief. This reciprocity distinguished the feudal bond from the naked subordination of slavery. Breaking the oath, whether by rebellion or failure of the lord’s obligations, invited severe consequences, ranging from confiscation of land to social disgrace and even death.

Oaths of fealty were not restricted to individual lords; they could also bind larger political and military communities. The Oaths of Strasbourg in 842, for example, formalized the alliance between Charles the Bald and Louis the German against their brother Lothar.13 Remarkably, the oaths were sworn in two languages, Romance and Old High German, to ensure mutual intelligibility among their respective troops. This illustrates how oaths not only created personal bonds but also cemented collective identities, bridging linguistic and cultural divides through ritualized speech.

Over time, as monarchies centralized and territorial states emerged, the nature of oaths began to shift. Loyalty was increasingly directed toward the king in his role as sovereign of a realm rather than simply as an individual lord among many.14 Nevertheless, the feudal oath retained its character as a personal pledge, deeply infused with religious invocation. It sacralized the hierarchy of medieval society and sustained a system in which loyalty was fragmented, layered, and always precarious. In this way, the oath of fealty became the medieval counterpart to Rome’s sacramentum, a performative utterance that stitched together fragile polities by binding men’s consciences to the persons above them.

Early Modern to Nineteenth Century: From Monarchical to Constitutional Oaths

The transition from the medieval order to early modern states altered the framework of military allegiance in profound ways. Where fealty had once been directed to a lord or a patchwork of overlapping authorities, the emergence of centralized monarchies and the doctrine of divine right reconfigured oaths as declarations of loyalty to the sovereign as the embodiment of the polity. In this sense, the early modern military oath marked a return to the Roman model; the soldier pledged his fidelity not to a constitution or abstract principle but to the person of the king, whose authority was conceived as absolute and divinely sanctioned.

In France under the Bourbons, for example, oaths emphasized loyalty to the king as God’s lieutenant on earth, a religiously inflected formula that fused obedience to ruler with obedience to heaven.15 England after the Tudor settlement witnessed similar transformations, where loyalty oaths to monarch and Church became litmus tests of both political and religious fidelity.16 The oath was not simply military but also confessional, ensuring conformity to the monarch’s faith as much as to his authority. Across early modern Europe, the personal oath to king or prince became a potent weapon of centralization, compelling subjects to acknowledge that all legitimate power flowed downward from sovereign to people.

The rise of constitutional states in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries gradually transformed the object of military allegiance once more. The American and French Revolutions in particular recast oaths as civic rather than personal, tethering loyalty to the constitution, the republic, or the nation.17 Revolutionary France demanded that its soldiers swear not to a monarch but to the nation and the law, a dramatic inversion of centuries of practice. In the United States, officers and enlisted men pledged to support the Constitution against foreign and domestic enemies, a novel formulation that placed ultimate authority in an enduring text rather than in a transient ruler.18

Germany offers an instructive case of continuity and change. Under the Kaiserreich, soldiers swore loyalty to the person of the emperor, Wilhelm II, reflecting the persistence of monarchic forms.19 After the collapse of the empire in 1918, however, the Weimar Republic instituted a new oath of allegiance to the constitution and lawful institutions of state.20 This shift mirrored the broader movement toward parliamentary democracy, though it would prove fragile in the face of authoritarian revival.

By the nineteenth century, then, Europe and the United States had developed divergent traditions of military allegiance, one still tethered to monarchs and theocratic justifications, the other increasingly committed to constitutions and abstract principles of law. These competing models of oath-taking revealed the stakes of political transformation. In monarchies, the oath reinforced the sacrality of the sovereign and the verticality of power; in republics, it became a ritual declaration of collective sovereignty and civic responsibility. Both traditions, however, preserved the fundamental logic inherited from Rome and feudalism, that military loyalty must be sacralized, sworn before witnesses both divine and human, and understood as a matter of ultimate obligation.

The U.S. Military Oath: Continuities, Reforms, and Constitutional Allegiance

The American experiment gave rise to one of the most distinctive traditions of military oath-taking in world history. Unlike the monarchies of Europe, where soldiers pledged themselves to the person of a sovereign, the framers of the United States insisted that loyalty be anchored not in a ruler but in a text, the Constitution. This reflected the core republican conviction that sovereignty resided in “We the People,” and that even the highest officers of the state were bound by written law rather than divine right or personal command.

The earliest American military oaths were crafted during the Revolutionary War. In 1775, the Continental Congress required officers to swear fidelity to the United States and obedience to Congress and the Continental Army’s commander, George Washington.21 By 1778, however, the formula shifted; Congress mandated that officers and soldiers pledge not only to obey superiors but also to “be true to the United States of America” and to “support, maintain, and defend the said United States.”22 This was a crucial innovation. While Washington’s authority remained central, allegiance was already being redirected toward the collective political entity rather than toward a single individual.

The Constitution of 1787 formalized this principle. Article VI declares that “the Senators and Representatives, and all executive and judicial Officers, both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution.”23 In placing the Constitution itself at the center, the framers embedded into law the idea that obedience must transcend transient officeholders. The military oath thus became an extension of this constitutional logic. Officers and enlisted personnel alike swore fidelity to the Constitution, an abstract framework of authority, while acknowledging lawful obedience to the president as commander in chief, but always in the context of constitutional supremacy.

Over time, the wording of the U.S. military oath underwent revisions that reflected the nation’s evolving political crises. During the Civil War, for instance, loyalty oaths were weaponized to root out Confederate sympathizers and to demand explicit repudiation of rebellion.24 In the twentieth century, amid world wars and the Red Scare, loyalty oaths expanded beyond the military, binding civil servants and educators under similar formulas of constitutional fidelity. These moments illustrate the elasticity of oath-taking; while the Constitution remained the object of allegiance, the political meaning of “support and defend” could shift depending on perceived threats.

The current oath, codified in Title 10 of the U.S. Code, requires enlisted members to declare, “I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic, and that I will obey the orders of the President of the United States and the orders of the officers appointed over me.”25 Notably, the clause places constitutional duty before presidential obedience, maintaining the principle that the executive is bound by law. Officers take a slightly different oath, one that omits obedience to superiors and instead emphasizes the defense of the Constitution above all else.26 This distinction underscores the framers’ concern that officers, entrusted with independent command, must remain especially vigilant against unlawful authority.

The U.S. military oath has therefore served as both a legal safeguard and a civic ritual. On one level, it is a binding act that legitimates the chain of command. On another, it is a performance of constitutional faith, reminding soldiers and officers that their ultimate loyalty is not to a man but to an idea. In moments of crisis, from the Civil War to the aftermath of January 6, 2021, the oath has been invoked as a moral compass, a reminder that military power must remain tethered to constitutional order.27 More than a formula of words, it is a ritual of republicanism, designed to ensure that the sword never outgrows the law.

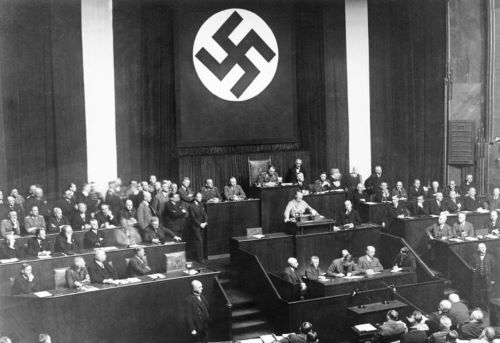

The German Case: From Monarchy, to Weimar, to the Führereid

The German tradition of military oaths illustrates both continuity with older monarchic models and the catastrophic consequences of transforming allegiance from constitution to individual. Under the Kaiserreich, soldiers of the Imperial German Army swore fidelity directly to the emperor, Wilhelm I and his successors. The oath bound them “to obey the Emperor unconditionally, even at the risk of life.”28 This formula echoed the feudal and absolutist heritage of Europe, where monarch and polity were inseparable, and where the sovereign’s person embodied the nation’s authority.

The collapse of the empire in 1918 and the establishment of the Weimar Republic produced a marked departure. In 1919, the new republican government instituted a military oath that pledged loyalty to the constitution and obedience to the lawful institutions of the state.29 This was a deliberate effort to anchor military allegiance in the democratic framework rather than in a monarch. The oath symbolized the republic’s fragile attempt to democratize authority in a society long accustomed to personal sovereignty. Yet the tradition of loyalty to a ruler lingered in cultural memory, and suspicion of abstract constitutionalism weakened the bond between soldiers and the new regime.

This weakness was decisively exploited by Adolf Hitler. Following the death of President Paul von Hindenburg on 2 August 1934, Hitler moved swiftly to consolidate his authority. That same day, the Reichswehr’s oath was rewritten as a Führereid, a personal pledge of “unconditional obedience” to Hitler himself.30 Soldiers now declared, “I swear by God this sacred oath: that I shall render unconditional obedience to the Führer of the German Reich and people, Adolf Hitler, supreme commander of the armed forces, and that I shall at all times be prepared, as a brave soldier, to give my life for this oath.”31 In one stroke, the institutional independence of the military was eradicated. The shift from allegiance to constitution and law to allegiance to a man fused the conscience of the armed forces to the will of the dictator.

The implications were immense. As historian Ian Kershaw has observed, the oath created a moral straitjacket for officers, who now perceived disobedience not only as treason but as sacrilege.32 At Nuremberg after the war, German officers repeatedly invoked the oath to justify their obedience to Hitler’s criminal orders.33 The oath thus became both shield and sword, a shield against moral accountability and a sword that enabled atrocities by sacralizing the Führer’s commands.

Yet the oath was not universally binding on conscience. The conspirators of the July 20, 1944 plot against Hitler wrestled with the legitimacy of breaking their sworn fidelity. Claus von Stauffenberg and others justified their actions by arguing that Hitler had himself betrayed the German people, thereby voiding the oath.34 Their tortured reasoning illustrates the destructive genius of the Führereid: it made rebellion against tyranny appear as perjury, and loyalty to law appear as treason.

In retrospect, the transformation of the German military oath in 1934 stands as one of the most consequential moments in modern history. It demonstrates the peril of collapsing civic allegiance into personal devotion. Where the United States anchored military loyalty in a constitution designed to outlast any individual, Nazi Germany bound its army to the breath of one man, and with that act, destroyed the final barrier between a professional military and a totalitarian state.

Comparative and Theoretical Reflections: Allegiance to Constitution vs. Allegiance to Person

The survey of Roman, medieval, American, and German traditions reveals a fundamental tension in the history of military oaths, whether allegiance should be sworn to an abstract principle or to an individual ruler. Each formulation carries profound consequences for political legitimacy, obedience, and resistance.

Oaths to individuals, whether emperors, kings, or dictators, concentrate loyalty in the person of the sovereign. They embody the principle that authority is inseparable from personality. This model, which stretches from the Roman imperial sacramentum through medieval homage to the Führereid, has the advantage of clarity; loyalty is absolute, simple, and visible in the person of the ruler. Yet it also contains inherent dangers. By sacralizing obedience to a single man, it makes moral and legal resistance extraordinarily difficult. The German military after 1934 illustrates this problem with devastating clarity; disobedience was not merely insubordination but sacrilege, binding soldiers’ consciences to Hitler’s will even when his orders violated natural law and humanity.35

By contrast, oaths to constitutions or laws distribute allegiance to abstract principles rather than to transient individuals. In the United States, the constitutional oath has functioned as a safeguard against tyranny by subordinating presidential authority to a higher legal framework.36 The soldier swears first to defend the Constitution, then to obey lawful orders. This ordering is not incidental but deliberate, reflecting the founders’ anxiety that unchecked obedience to a ruler could replicate the very monarchical abuses they had rebelled against. The constitutional oath thus enshrines a right, even a duty, to disobey unlawful orders, a principle reinforced in American military law and echoed in international norms established after World War II.37

Yet constitutional oaths are not without their ambiguities. Abstract loyalty can seem less compelling than personal devotion, particularly in times of crisis. Soldiers may struggle to interpret what it means to “support and defend” a constitution when political factions contest its meaning. During the U.S. Civil War, both Union and Confederate forces claimed fidelity to constitutional principles, illustrating how competing interpretations can fracture allegiance.38 In such contexts, the abstraction of the oath can produce not unity but division.

The oath also functions as what scholars of political theory describe as a performative speech act, an utterance that constitutes rather than merely describes allegiance.39 To swear is to enact loyalty in public, before both human witnesses and transcendent guarantors. The ritualized form of oaths, whether kneeling before a medieval lord or raising a right hand before a Constitution, reveals their dual function; they create political communities by binding individuals through language, and they sanctify obedience by placing it under divine or moral sanction. This performative quality explains their persistence across centuries, even as their objects of allegiance have shifted.

The comparison between the United States and Nazi Germany underscores the stakes of these choices. In the U.S. model, the Constitution’s primacy in the oath creates a legal shield against dictatorship, however fragile. In Nazi Germany, the transformation of the oath into a personal pledge destroyed institutional independence and enabled atrocities. The contrast suggests that while no formula can guarantee moral courage, oaths oriented toward constitutions rather than rulers better preserve the possibility of lawful dissent and democratic resilience.

Conclusion

The history of military oaths, from Rome’s sacramentum to the medieval oath of fealty, from the U.S. constitutional formula to Hitler’s Führereid, charts a trajectory of political imagination. At every stage, the oath has functioned as more than a mere formality. It is a ritual act that sanctifies authority, binds soldiers to obedience, and reveals the locus of sovereignty within a given society. Whether spoken before the gods of Rome, a medieval lord, a constitutional text, or a dictator, the oath is at once legal, religious, and performative. It declares where ultimate loyalty lies.

The Roman model sacralized allegiance to the state, merging civic identity with religious obligation. The medieval system, by contrast, fragmented loyalty into webs of personal fealty, stabilizing a society without centralized authority. The modern world reconfigured the oath yet again, as constitutional republics sought to anchor allegiance in law rather than personality. This innovation proved both radical and fragile, radical in its assertion that the sword must obey not a man but a text, fragile in that constitutions themselves can be contested, manipulated, or overthrown.

The German transformation of 1934 demonstrates the catastrophic danger of collapsing civic allegiance into personal devotion. By binding the Wehrmacht’s conscience to Adolf Hitler rather than to a constitution, the Führereid obliterated the last institutional barrier to totalitarian rule. Soldiers became instruments of a man, not defenders of a people, and the oath itself became a weapon of tyranny. In contrast, the American model illustrates how constitutional oaths can at least preserve the possibility of lawful resistance. While no formula guarantees moral courage, for even constitutional oaths can be perverted or ignored, allegiance to principle rather than to personality creates the institutional space for dissent.

The comparative lesson is clear. Military oaths are not trivial ceremonies but barometers of political legitimacy. They expose whether a society grounds its authority in enduring law or in transient rulers. They also reveal the fragility of institutions, for even the most abstract oath depends on human actors willing to uphold its meaning. History thus warns us that the wording of an oath can alter the fate of nations. To swear by constitution or by king, by law or by dictator, is to decide in advance the possibilities of obedience, resistance, and freedom.

Appendix

Footnotes

- “Sacramentum (oath),” Wikipedia, last modified August 24, 2023.

- “Fealty: Love, Loyalty, and Choice in Feudalism,” History Medieval, accessed September 28, 2025.

- Todd DePastino, “The Oath: A History,” Veterans Breakfast Club, accessed September 28, 2025.

- “Hitler Oath,” Wikipedia, last modified September 19, 2025.

- “Sacramentum (oath),” Wikipedia.

- Ibid.

- Tertullian, De Corona 11, trans. at https://www.tertullian.org/works/de_corona.htm.

- David W. Krieger, “Sacramentum: Military Oath and Christian Martyrdom,” in Sacred Violence in Early Christianity (Swarthmore Classics Faculty Works).

- “Sacramentum (oath),” Wikipedia.

- “Homage (feudal),” Wikipedia, last modified July 27, 2024.

- Ibid.; “Fealty: Love, Loyalty, and Choice in Feudalism,” History Medieval.

- “Fealty: Love, Loyalty, and Choice in Feudalism,” History Medieval.

- “Oaths of Strasbourg,” Wikipedia, last modified August 12, 2024.

- Susan Reynolds, Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

- Julian Swann, Exile, Imprisonment, or Death: The Politics of Disgrace in Bourbon France, 1610–1789 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 92–95.

- John Guy, Tudor England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 306–10.

- Lynn Hunt, Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 125–30.

- DePastino, “The Oath: A History.”

- Seligmann, Matthew S. and McLean, Roderick R, Germany from Reich to Repubilc, 1971-1918 (New York: Macmillan, 2000).

- “German Military Oaths,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia, accessed September 28, 2025.

- DePastino, “The Oath: A History.”

- Ibid.

- U.S. Constitution, art. VI, cl. 3, https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/article-6/.

- Harold M. Hyman, To Try Men’s Souls: Loyalty Tests in American History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1959), 63–85.

- 10 U.S.C. § 502 (current), https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/10/502.

- 5 U.S.C. § 3331 (current), https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/5/3331.

- DePastino, “The Oath: A History.”

- “German Military Oaths,” USHMM Encyclopedia.

- Ibid.

- “Hitler Oath,” Wikipedia.

- “The Reichswehr Swears an Oath of Allegiance to Adolf Hitler on the Day of Hindenburg’s Death (August 2, 1934),” German History in Documents and Images.

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler: 1936–1945, Nemesis (New York: W. W. Norton, 1980), 165–68.

- “Hitler Oath,” Wikipedia.

- Peter Hoffmann, Stauffenberg: A Family History, 1905–1944 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 289–95.

- Kershaw, Nemesis, 165–68.

- DePastino, “The Oath: A History.”

- United States v. Calley, 22 U.S.C.M.A. 534 (1973); “Principles of International Law Recognized in the Charter of the Nürnberg Tribunal and in the Judgment of the Tribunal,” U.N. General Assembly (1950), https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/draft_articles/7_1_1950.pdf.

- Hyman, To Try Men’s Souls, 70–75.

- Gregor Noll, “Killing Hitler Word by Word: The Oath as Apocalyptic,” Grievance: An International Journal of Human Rights (2025).

Bibliography

- DePastino, Todd. “The Oath: A History.” Veterans Breakfast Club. Accessed September 28, 2025. https://veteransbreakfastclub.org/the-oath-a-history/.

- German History in Documents and Images. “The Reichswehr Swears an Oath of Allegiance to Adolf Hitler on the Day of Hindenburg’s Death (August 2, 1934).” Accessed September 28, 2025. https://germanhistorydocs.org/en/nazi-germany-1933-1945/the-reichswehr-swears-an-oath-of-allegiance-to-adolf-hitler-on-the-day-of-hindenburgs-death-august-2-1934.

- “German Military Oaths.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia. Accessed September 28, 2025. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/german-military-oaths.

- Guy, John. Tudor England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Hoffmann, Peter. Stauffenberg: A Family History, 1905–1944. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Hunt, Lynn. Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

- Hyman, Harold M. To Try Men’s Souls: Loyalty Tests in American History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1959.

- Kershaw, Ian. Hitler: 1936–1945, Nemesis. New York: W. W. Norton, 1980.

- Noll, Gregor. “Killing Hitler Word by Word: The Oath as Apocalyptic.” Grievance: An International Journal of Human Rights (2025). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42439-025-00106-w.

- “Oaths of Strasbourg.” Wikipedia. Last modified August 12, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oaths_of_Strasbourg.

- “Sacramentum (oath).” Wikipedia. Last modified August 24, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacramentum_(oath).

- Reynolds, Susan. Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Swann, Julian. Exile, Imprisonment, or Death: The Politics of Disgrace in Bourbon France, 1610–1789. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Tertullian. De Corona. Translated text at https://www.tertullian.org/works/de_corona.htm.

- “Fealty: Love, Loyalty, and Choice in Feudalism.” History Medieval. Accessed September 28, 2025. https://historymedieval.com/fealty-love-loyalty-and-choice-in-feudalism/.

- “Hitler Oath.” Wikipedia. Last modified September 19, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hitler_Oath.

- Seligmann, Matthew S. and McLean, Roderick R. Germany from Reich to Repubilc, 1971-1918. New York: Macmillan, 2000.

- U.S. Constitution, Article VI, Clause 3. https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/article-6/.

- United States Code, 5 U.S.C. § 3331. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/5/3331.

- United States Code, 10 U.S.C. § 502. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/10/502.

- United Nations. “Principles of International Law Recognized in the Charter of the Nürnberg Tribunal and in the Judgment of the Tribunal,” 1950. https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/draft_articles/7_1_1950.pdf.

- Krieger, David W. “Sacramentum: Military Oath and Christian Martyrdom,” in Sacred Violence in Early Christianity (Swarthmore Classics Faculty Works). https://works.swarthmore.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1048&context=fac-classics.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.29.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.