The prehistoric and early ethno-linguistic peoples of Venezuela stand as witnesses to the region’s role as both origin and crossroads.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The question of who first walked the landscapes of what we now call Venezuela opens onto a terrain at once archaeological, linguistic, and historical. This land, poised between the Caribbean Sea, the Amazon basin, and the northern Andes, did not serve merely as a backdrop for scattered prehistoric communities but as a corridor, a cradle, and a crossroads.

To write its earliest history requires a critical voice, one willing to balance fragmentary evidence with interpretive care, to acknowledge both the silences of archaeology and the claims of linguistic descent. In so doing, Venezuela emerges not as a periphery to greater civilizational centers but as a space of origination, diffusion, and endurance.

The Earliest Human Presence

Paleo-Indian Settlements

Archaeological traces suggest human presence in Venezuela as early as 13,000 to 15,000 years ago. The El Jobo culture, centered in Falcón state, reveals the earliest lithic traditions in the region, notable for finely worked projectile points and tools adapted to hunting megafauna.1 Nearby, the Taima-Taima site produced a remarkable assemblage: the bones of mastodons bearing cut marks from stone blades, a scene that arrests the imagination with its juxtaposition of human ingenuity and Pleistocene life.2

These finds situate Venezuela firmly within the broader wave of Paleo-Indian settlement across the Americas. Yet they also hint at a particular ecological adaptation. Rather than remaining mere passersby in a continental migration, these groups left behind signs of a sustained relationship with local landscapes, a harbinger of the cultural depth that would follow.

Subsistence Patterns

As climates shifted and megafauna disappeared, subsistence patterns changed. Venezuela’s early peoples turned to fishing, small-game hunting, and the gathering of wild plants. Archaeological sites suggest increasing familiarity with riverine resources, a foreshadowing of the Orinoco basin’s later importance as both a natural larder and a cultural artery. The trajectory from megafauna hunting to diversified subsistence speaks not simply to necessity but to the flexibility that undergirded later cultural florescence.

The Archaic and Formative Periods

Coastal Adaptations

By the mid-Holocene, coastal Venezuela bore evidence of complex fishing communities. Shell middens along the Caribbean shore record intensive exploitation of marine resources, while early ceramic fragments point to the beginnings of technological innovation.3 These communities were not marginal but central in their own right, forging ways of life tied to tides and estuaries rather than uplands or forests.

Agricultural Innovations

The Orinoco basin became one of South America’s hearths of cassava cultivation. Manioc griddles and associated artifacts reveal a decisive turn toward agriculture, even if it coexisted with hunting and gathering.4 Cassava’s resilience to tropical soils gave these communities a reliable food base, enabling denser populations and more complex social organization. Agriculture here did not mimic Andean terracing nor Amazonian forest-gardening but represented a hybrid strategy suited to the mosaic of environments stretching from savannas to gallery forests.

Regional Diversity

One cannot write of Venezuela as a unitary cultural zone. In the Llanos, river and savanna defined seasonal rhythms of life. In the Andes, small communities adapted to highland ecologies with terracing and irrigation. On the Guiana Shield, peoples engaged in foraging and incipient agriculture, navigating rocky uplands and vast rivers. Diversity was not fragmentation but strength, ensuring that multiple lifeways could persist side by side.

Early Ethno-Linguistic Peoples

The Arawak Tradition

Among the earliest ethno-linguistic formations to shape Venezuela were the Arawak-speaking peoples. The Orinoco basin has long been identified as their homeland, from which they spread across northern South America and into the Caribbean.5 By the first millennium CE, Arawakan migrations reached the Antilles, culminating in the Taíno. On the mainland, groups such as the Caquetío occupied regions of western Venezuela, extending to the islands of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. Their linguistic and cultural ties to the Taíno illustrate Venezuela’s role as a springboard into the wider Caribbean.

Cariban Expansions

The Cariban-speaking peoples represented another enduring current. They dominated parts of eastern Venezuela and the Guiana Shield, often contrasted with the Arawaks in their martial orientation and looser social structures.6 Oral traditions and colonial accounts depict them as formidable warriors, yet such portrayals often reflect European anxieties more than indigenous self-definition. Archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests a people skilled at navigating river systems, maintaining networks of trade, and adapting to diverse environments.

The Timoto-Cuica

In the Andean highlands lived the Timoto-Cuica, a relatively isolated but sophisticated culture. They constructed terraced fields and irrigation systems, cultivated potatoes and maize, and produced finely woven textiles. Unlike the more dispersed Arawaks and Caribs, the Timoto-Cuica developed high population densities in compact valleys. They were not a state nor an empire but a cluster of chiefdoms that balanced autonomy with shared cultural practices.

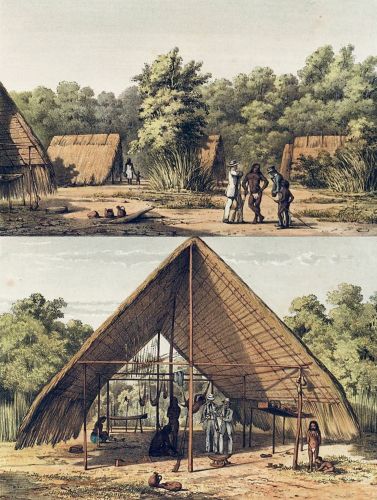

Coastal and Island Peoples

On the Caribbean coast and nearby islands lived groups such as the Cumanagoto and Guaiquerí. These peoples based their economies on fishing, salt extraction, and exchange with inland groups. They stood at the hinge between mainland and island worlds, illustrating again how Venezuela’s geography fostered not isolation but connection.

Venezuela in the Wider Indigenous Context

Venezuela as a Bridge

Venezuela must be seen as a bridge linking the Andes, Amazonia, and the Caribbean. Technologies such as cassava processing, ceramic traditions, and canoe navigation flowed through its riverine arteries. Peoples here did not merely receive influences but transmitted them outward, shaping the trajectory of entire regions.

Comparative Ethno-Linguistics

Linguistic analysis highlights the interplay of Arawakan, Cariban, and Chibchan families. While Arawakan languages reveal deep continuities across thousands of miles, Cariban tongues mark eastward expansion and conflict. Chibchan speakers in the western fringes underscore Venezuela’s Andean connections.7 The linguistic map thus mirrors the geographic one, with the territory serving as both intersection and frontier.

Continuity and Change

Colonial encounters fractured but did not erase these indigenous presences. Many groups endured, some assimilated into colonial economies, others retreating into marginal zones. Yet even in the present, the persistence of Wayuu, Pemon, and other communities testifies to a continuity that resists the narrative of disappearance.

Archaeological and Historiographical Debates

Challenges of Evidence

The tropical climate often erodes the archaeological record. Organic materials decay rapidly, forcing reliance on ceramics, lithics, and linguistic reconstruction. These limitations mean that much of Venezuela’s prehistory remains shadowed, a challenge that historians must confront with humility.

The Taíno Question

Scholars have long debated whether the Taíno should be considered “Venezuelan” in origin. The Orinoco basin was almost certainly their launching point, yet by the time Europeans arrived they lived in the Antilles. To claim them as indigenous to Venezuela risks collapsing the distinction between ancestral homelands and cultural identities forged elsewhere. At stake is not only scholarly accuracy but the recognition of multiple claims to belonging.

Future Directions

Recent advances in radiocarbon dating, paleoethnobotany, and genetic analysis promise to clarify the deep history of Venezuela’s peoples. Ancient DNA studies may trace lineages across millennia, linking El Jobo hunters to contemporary indigenous groups. The historiography thus remains unfinished, a living field of inquiry.

Conclusion

The prehistoric and early ethno-linguistic peoples of Venezuela stand as witnesses to the region’s role as both origin and crossroads. From mastodon hunters at Taima-Taima to cassava cultivators along the Orinoco, from Arawak migrations into the Antilles to the highland terraces of the Timoto-Cuica, these communities shaped a world both local and expansive. To study them is to recover not only fragments of the past but to reimagine Venezuela as central to the story of the Americas.

Appendix

Footnotes

- José M. Cruxent and Irving Rouse, Archaeology of Venezuela (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963), 22–25.

- Sanoja, Mario, and Iraida Vargas, Venezuela: Historia, Política y Sociedad (Caracas: Monte Ávila, 1987), 17.

- Cruxent and Rouse, Archaeology of Venezuela, 56–59.

- Anna C. Roosevelt, “Resource Management in Amazonia before the Conquest,” Advances in Economic Botany 7 (1989): 42-44.

- Peter Hulme, Colonial Encounters: Europe and the Native Caribbean, 1492–1797 (London: Routledge, 1986), 31.

- Corinne L. Hofman, et.al., “Colonial Encounters in the Southern Lesser Antilles: Indigenous Resistance, Material Transformations, and Diversity in an Ever-Globalizing World” in Material Encounters and Indigenous Transformations in the Early Colonial Americas, (London: Brill, 2019), 359-384.

- John Alden Mason, The Languages of South American Indians (New York: Cooper Square Publishers, 1950), 211–14.

Bibliography

- Cruxent, José M., and Irving Rouse. Archaeology of Venezuela. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963.

- Hofman, Corinne L., et.al. “Colonial Encounters in the Southern Lesser Antilles: Indigenous Resistance, Material Transformations, and Diversity in an Ever-Globalizing World” in Material Encounters and Indigenous Transformations in the Early Colonial Americas. London: Brill, 2019.

- Hulme, Peter. Colonial Encounters: Europe and the Native Caribbean, 1492–1797. London: Routledge, 1986.

- Mason, John Alden. The Languages of South American Indians. New York: Cooper Square Publishers, 1950.

- Roosevelt, Anna C. “Resource Management in Amazonia before the Conquest.” Advances in Economic Botany 7 (1989): 30-62.

- Sanoja, Mario, and Iraida Vargas. Venezuela: Historia, Política y Sociedad. Caracas: Monte Ávila, 1987.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.11.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.