By Amanda Berman

Curatorial Assistant, Department of Sculpture and Decorative Arts

Getty Museum

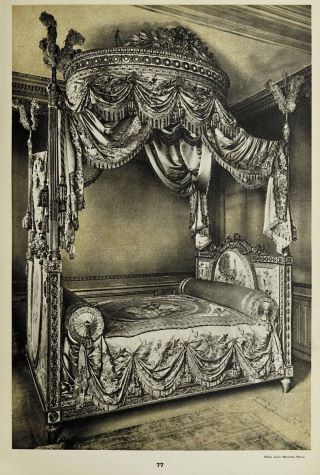

With its grand size and luxurious upholstery, this bed makes a statement. However, it is also special because we know so much about it. It’s unusual for an 18th-century piece of furniture, no matter how ornate, to have such a well-documented life. One particular owner, a woman named Gilda Darthy, sold this bed in 1923, along with much of her art collection, at auction in Paris.

The sale catalog advertises about 100 lots of furniture from Darthy’s collection: ceramics, paintings, sculptures, and more. It contained paintings attributed to the French 18th-century painter François Boucher and Italian painter Francesco Guardi, and a sculpture in marble by Italian sculptor Francesco Ladatte. She owned vases decorated with cloisonné enamel from China, a furniture set upholstered in 18th-century tapestries, gilt-bronze candlesticks, and a rolltop desk with inlaid wood designs. This bed was one of the highlights of the auction, with a full-page picture showing that it still possessed some remarkably preserved original upholstery.

The upholstery on the bed today uses modern fabrics in a historic pattern (the museum has the surviving original upholstery in storage for researchers to examine). The catalog made clear that Darthy had a sizeable art collection, but somehow, we didn’t know much about her.

Newspapers, magazines, and other publications from the time tell a story about Darthy. She made a career as a Parisian music hall singer and stage actress. She performed mostly in France but also made appearances in the United States. In 1902, she was the third person ever to play Roxanne in Cyrano de Bergerac, probably her best-known role. The society sections of Parisian newspapers mention her often and discuss her many love affairs and social exploits.

Photos of her, mainly taken by the Reutlinger studio (known for its portraits of celebrities), show her personality.

She’s a confident, stylish lady who is using her fame and beauty to further enhance her status (the studio sold small prints of these photos). The variety in these pictures represents her versatility as an actress and showcases her interest in fashion. Notice the table in the far-right image—though likely a studio prop, her posing with it demonstrates an interest and preference for 18th-century styles. Perhaps another indication of her interest in art and antiques are the costumes she wears. As an actress, she portrayed a few historical figures, with her most famous being Madame de Montespan (mistress of King Louis XIV) in the play L’Affaire des Poisons.

Knowledge about her art collection, combined with photos and newspaper articles, provides evidence of her interest in collecting. These contemporary sources gave us some information about her, but unfortunately, they only tell part of the story. Reporters in the early 1900s certainly wrote articles about other art collections or important collectors paying high prices for art, but when it comes to Darthy, they wrote more about her social life than her collecting practices or even her acting career. The only time the newspapers mention Darthy’s art collection is at the time of this sale.

Women have often been obscured in the art historical record. This focus on a woman’s looks or social life is one way, but another example is when historical sources define women primarily by their relationships with men, both familial and romantic. A common form is documents referring to a married woman as “Mrs.” and the husband’s full name, but this method of erasure holds true for unmarried women like Darthy as well. When the press mentioned her, even when discussing her theater career, they usually also referenced her famous lover, Henri de Rothschild. Linking women to men in their lives instead of treating them as people in their own right contributes to the erasure that has been a longstanding Western societal practice.

A record related to Darthy’s bed illustrates this idea of erasure as well. Darthy bought this bed from the art dealer firm Duveen, but Duveen had it stored at the warehouse of another dealer, Carlhian. Carlhian’s records note that “M. de Rothschild” came to see the bed, which probably refers to Henri. It’s telling that there’s no mention of Darthy. Perhaps Rothschild accompanied Darthy that day to see the bed, and someone at Carlhian only recorded his visit, leaving out the woman with him. Whoever wrote this record may have assumed he purchased the bed. Situations like these obscure women from the art historical record, and imply that they couldn’t form their own collection.

History has treated Darthy, like many women, one-dimensionally, focusing mostly on her social life. Further research shows her as an actress, a socialite, and an art collector. While Darthy may not have been a prominent art collector, the fact that we didn’t know much about her and that so little documentation of her collecting activities exists says something about the way history treats women. Women are frequently relegated to supporting roles in the historical narrative, and discovering their diverse stories takes some digging.

Originally published by The Iris, 03.24.2021, under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.