The colonists left a European society in which church and state were closely interconnected.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

On September 12, five days before the Convention adjourned, Mason and Gerry raised the question of adding a bill of rights to the Constitution. Mason said: It would give great quiet to the people; and with the aid of the State declarations, a bill might be prepared in a few hours.

But the motion of Gerry and Mason to appoint a committee for the purpose of drafting a bill of rights was rejected. Again, on September 14, Pinckney and Gerry sought to add a provision that the liberty of the Press should be inviolably observed—.

But after Sherman observed that such a declaration was unnecessary, because [t]he power of Congress does not extend to the Press,

this suggestion too was rejected. It cannot be known accurately why the Convention opposed these suggestions. Perhaps the lateness of the Convention, perhaps the desire not to present more opportunity for controversy when the document was forwarded to the states, perhaps the belief, asserted by the defenders of the Constitution when the absence of a bill of rights became critical, that no bill was needed because Congress was delegated none of the powers which such a declaration would deny, perhaps all these contributed to the rejection.

In any event, the opponents of ratification soon made the absence of a bill of rights a major argument, and some friends of the document, such as Jefferson, strongly urged amendment to include a declaration of rights. Several state conventions ratified while urging that the new Congress to be convened propose such amendments, 124 amendments in all being put forward by these states. Although some dispute has occurred with regard to the obligation of the first Congress to propose amendments, Madison at least had no doubts and introduced a series of proposals, which he had difficulty claiming the interest of the rest of Congress in considering. At length, the House of Representatives adopted 17 proposals; the Senate rejected two and reduced the remainder to twelve, which were accepted by the House and sent on to the states where ten were ratified and the other two did not receive the requisite number of concurring states.

Overview of the Religion Clauses

First Amendment:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The first two provisions of the First Amendment, known as the Religion Clauses, state that Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.

The Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses were ratified as part of the Bill of Rights in 1791 and apply to the states by incorporation through the Fourteenth Amendment. Together with the constitutional provision prohibiting religious tests as a qualification for office, these clauses promote individual freedom of religion and separation of church and state.

The Supreme Court has acknowledged that the Religion Clauses are not the most precisely drawn portions of the Constitution.

The Framers’ goal was to state an objective, not to write a statute.

The clauses are cast in absolute terms

and either, if expanded to a logical extreme, would tend to clash with the other.

Accordingly, the Court has said that rigidity could well defeat the basic purpose of these provisions, which is to insure that no religion be sponsored or favored, none commanded, and none inhibited.

The breadth of the Clauses has allowed debates over their proper scope since ratification. It has also led to some internal inconsistency

in the Supreme Court’s opinions interpreting these clauses, as well as interpretations that have shifted over time.

The following essays discuss the historical background of the Religion Clauses, including a discussion of colonial religious establishments and the shift in early America towards greater religious freedom. Next, essays address how both clauses prevent the government from interfering in certain religious disputes. Essays then examine, in turn, Supreme Court interpretations of the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause. Finally, two essays explore the relationship between the two Religion Clauses, as well as the relationship between the Religion Clauses and the First Amendment’s Free Speech Clause.

One preliminary issue broadly relevant across Religion Clause jurisprudence is what the First Amendment means when it refers to religion.

Some early cases suggested that courts might determine what is properly considered to be religion.

In an 1890 case rejecting a Free Exercise Clause challenge to a law disenfranchising polygamists, the Court said calling the advocacy of polygamy a tenet of religion

would offend the common sense of mankind.

Later cases, however, seemed to retreat from this suggestion as they restricted the ability of the government, including courts, to judge the legitimacy of religious beliefs. Nonetheless, the Religion Clauses extend only to sincere religious activities, and in evaluating constitutional claims, the government may investigate whether a person’s beliefs are insincere and whether they are secular, stemming from political, sociological, or philosophical views rather than religious beliefs.

A religious belief may fall within the scope of the clauses even if it is not consistent with the tenets of a particular Christian sect, and non-Christian religions are also protected. One 1965 case noted the ever-broadening understanding of the modern religious community,

discussing conceptions beyond even traditional theism. In an Establishment Clause case decided a few years earlier, the Court had stated that the government may not aid all religions as against non-believers,

or aid those religions based on a belief in the existence of God as against those religions founded on different beliefs.

Introduction to the Historical Background of the Religion Clauses

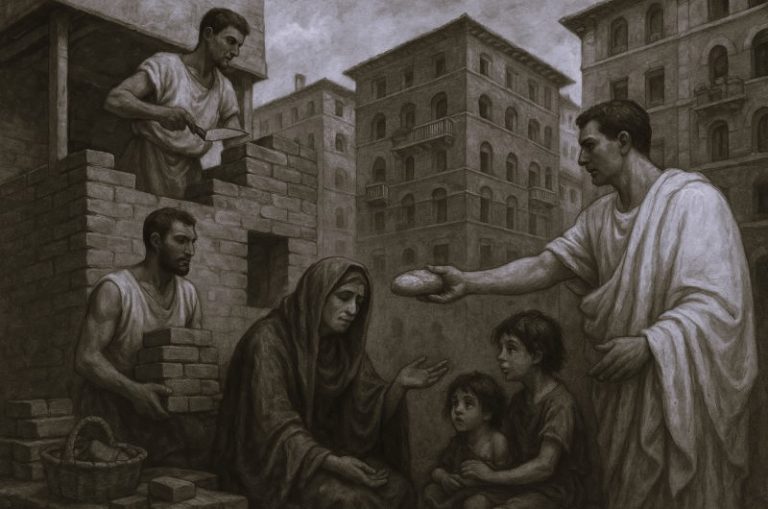

As the Supreme Court has recognized, many colonists left Europe and settled in America to escape the bondage of laws which compelled them to support and attend government-favored churches.

Scholars have described the modern concepts of religious liberty

and separation of church and state

as originating with the development of the United States. The Framers of the Religion Clauses built upon almost two centuries of historical developments that shaped this American model of religious freedom after the arrival of the earliest colonists. During these formative years-and even after the First Amendment’s ratification-the concept of freedom of religion lacked a fixed meaning. The concept evolved significantly over the colonial period in tandem with political and social movements. Accordingly, while the Supreme Court has often suggested that colonial and Revolutionary history is important in determining the meaning of the Religion Clauses, jurists and historians have disagreed about which history appropriately informs the Clauses, given the complexity and variability of that history.

The colonists left a European society in which church and state were closely interconnected. Historically, political leaders throughout the world believed that a government could not legislate to preserve public morals or maintain civil order unless the state based its rule in a religion that was followed by the populace. The features of historic state-sponsored religions, known as religious establishments,

included a government-recognized state church; laws outlining religious orthodoxy or church governance; compulsory church attendance; state financial support for the church; proscriptions on religious dissent; the limitation of political participation to the state church’s members; and the use of churches for civil functions such as education or marriage.

Even in colonial times, there were debates about what types of state support for religion created a religious establishment,

and what level of state support was appropriate. Although some of the colonists may have fled religious persecution in England and other European countries, many New World colonies initially mandated the practice of a specific religion and persecuted those who did not comply. Some of the colonies that did not designate a single official religion still limited citizenship to Christians and adopted other hallmarks of an established state religion.

During the colonial period and Revolution, however, some colonies began to recognize broader conceptions of religious liberty and embrace greater separation between church and state. Delegates to the Continental Congress expressed diverse views on the issue in debates leading up to the adoption of the First Amendment’s Religion Clauses. Although the Religion Clauses immediately constrained the federal government, some states continued to support religious establishments even after the First Amendment’s ratification. Nonetheless, all states had disestablished religion decades before the Supreme Court held that states were legally obligated to comply with the Religion Clauses through the Fourteenth Amendment, reflecting continued debates and shifting attitudes towards religious liberty.

England and Religious Freedom

Religious freedom has played a central role in the mythos of the United States’ Founding. Accordingly, the Supreme Court has sometimes looked to state sponsorship of religion prior to the Founding to determine what the drafters of the First Amendment’s Religion Clauses intended to reject. While a unified church and state was once the dominant governance model worldwide, the Church of England provides one particularly salient example of a state religion that was familiar to the Founders.

King Henry VIII established the Church of England through the Act of Supremacy in 1534, and Queen Elizabeth reestablished the Church in 1559 after a period of political and religious turbulence. The Church of England’s establishment placed the country’s ecclesiastical courts under domestic control rather than under the control of the Pope. These ecclesiastical courts, which operated in parallel with England’s civil courts, had jurisdiction over purely religious matters such as spiritual nonconformity; so-called moral offenses such as drunkenness or adultery; and disputes over marriages, tithes, wills, and defamation.

Following the end of the English Civil War in 1651, four acts collectively known as the Clarendon Code reentrenched the church. One of these laws, the Act of Uniformity of 1662, prescribed a common form of worship and required ministers to follow this form of worship to hold religious office. Other laws limited officeholding to Anglicans and restricted non-Anglican worship. The ecclesiastical courts were also restored in 1661 with largely unchanged jurisdiction, although use of the courts declined significantly over the ensuing decades.

Thus, English laws preferred members of the established Church of England, excluded dissenters, and commingled ecclesiastical and civil functions. The government dictated official modes of worship, claimed jurisdiction over areas such as education and marriage that had previously been governed by the Roman Catholic Church, required membership in the established church to be considered a legal citizen, and criminalized religious dissent. Nonetheless, the government did not view the Act of Uniformity as violating freedom of conscience: in England’s view, while it dictated public observance of religion and prevented dissenters from undermining the established church, it did not dictate private beliefs.

The Toleration Act of 1689 lifted criminal penalties for nonconformists’ public worship if the dissenters took certain oaths or declared their loyalty to the crown and professed their Christian belief. However, the law did not extend the right of public worship to Roman Catholics or other non-Protestant dissenters, and all non-Anglicans continued to be barred from holding public office. Furthermore, the Church of England retained its special status. England considered the Toleration Act to apply directly to the colonies. As discussed in subsequent essays, this Act granted more religious liberty than some of the colonies did at the time and influenced those colonies to move toward further religious freedom.

The Colonies and Religious Freedom

At least initially, the colonies largely continued the historical practice of having state-established religion in America; although not every colony had one officially designated state religion, every colonial government had some elements of a religious establishment,

as defined in an earlier essay. Nonetheless, even the colonies that did designate and support an official religion viewed their own governments as quite different from the English system.

The first English colony, Virginia, illustrates the evolving approach to government and religion. Virginia established the Church of England as the colony’s official church. Early governors adopted martial laws requiring daily worship and prohibiting blasphemy, among other provisions prescribing religious order. The government supported and required conformity to the established church, and church vestries exercised semi-civil political functions. As England reetrenched the established church after the English Civil War, Virginia followed the crown’s instructions by supporting the church. Among other provisions, Virginia laws adopted in 1661 and 1662 required colonists to erect churches and support ministers at public expense, prescribed proper forms of worship, and punished those who publicly worshipped outside the established church. However, in contrast to England, the civil government rather than church authorities assumed jurisdiction over marriages, wills, and the appointment of ministers-although such functions were, by law, carried out in accordance with the Church of England’s doctrines. The Church of England was also established in the Carolinas, but those colonies tolerated a greater diversity of religious views than Virginia.

The New England colonies of Plymouth, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Haven were established by Puritans who similarly provided for colonial government sponsorship of that religion. These colonies sought to establish a unified community operating according to a pure

religious doctrine that followed the first Plantation of the Primitive Church

rather than the established Church of England. In Massachusetts Bay, Puritans mandated the construction and financial support of Congregational churches. A public confession of faith was necessary to become a citizen of the colony. Dissenters in these colonies were punished harshly with imprisonment or expulsion, and Massachusetts executed four Quakers between 1658–1661. Nonetheless, Puritan churches were independent associations that lacked a central church authority in the manner of the Church of England.

Although New England Puritans operated their colonies according to religious doctrine, they distinguished civil from religious authority, and clergy could exercise authority only over religious affairs. Notably, the Puritans did not create ecclesiastical courts, which they had protested in England. The Puritans’ conception of separate spheres of authority, however, did not preclude the civil government from prosecuting idolatry or blasphemy. In the Puritans’ view, liberty of conscience did not encompass the liberty to practice religious error. Accordingly, punishing those who deviated from religious doctrine did not violate liberty of conscience, and the government could punish public deviations or errors without improperly invading the church’s authority.

There is some debate over whether there was an established church in the colony of New York, in the sense of an officially designated state church. New York, like the Carolinas, demonstrated the conflict between the unpopular established Church of England and other, more popular religious causes. The colony guaranteed free religious exercise to all Christians but required parishes to select ministers and collect taxes to establish and support churches at the local level. Following the Toleration Act’s adoption in England, New York excluded Catholics from guarantees of the liberty of conscience and adopted the Ministry Act of 1693, which required the settling of a ministry.

There was debate over whether this act referred only to Anglican ministers, or whether the language was broad enough to allow towns to select other Protestant ministers.

Maryland somewhat similarly faced pressure from the Church of England after initially tolerating more religious diversity. Early colonial leaders were Catholic and seemed to hope that Catholics and Protestants could live together peacefully in Maryland. Lord Baltimore largely ignored his authority from England to build and dedicate Anglican churches, along with requests from Catholics for special government recognition. In 1649, Maryland adopted the Act Concerning Religion, which guaranteed that no person professing to believe in Jesus Christ

could be troubled in the free exercise of religion-but also decreed strict penalties for blasphemy by non-Trinitarians. However, following political and religious upheaval in the colony, in the late 1600s and early 1700s, the Maryland government adopted laws depriving Catholics of their previously held civil rights and, ultimately, establishing the Church of England.

Colonial Conceptions of Religious Liberty

Although the colonies did not grant full religious freedom as the concept would be understood today, some nonetheless refrained from establishing an official state-sponsored church and granted more religious liberty than, for example, Virginia or the Puritan colonies.

Rhode Island granted more religious liberty than other New England colonies. Roger Williams, the founder of Rhode Island, was expelled from Massachusetts Bay for criticizing the Puritan government and arguing for a stronger separation between church and state. Williams was himself a Puritan minister who sought to propagate the true church

—but he believed this could be achieved only by maintaining a wall of Separation between the Garden of the Church and the Wildernes[s] of the world.

In a pamphlet published in England, Williams argued against civil persecution for matters of conscience, writing that civil states should not be the judges of spiritual matters.

Rhode Island’s royal charter granted liberty of conscience, providing that no person would be molested, punished, disquieted or called in question, for any differences in opinion in matters of religion,

so long as the person did not actually disturb the civil peace.

To preserve this civil peace, however, the civil government prohibited crimes such as adultery and fornication, and required observance of the Sabbath. Furthermore, the colony adopted laws limiting citizenship and public office to Protestants. Nonetheless, Rhode Island did not adopt criminal laws persecuting the few Catholic and Jewish people residing within the colony, and in contrast to other New England colonies, Rhode Island generally found no reason to charge Quakers with breach of the civil peace.

Pennsylvania also granted some religious liberty. William Penn, a Quaker, founded Pennsylvania in 1681 as a holy experiment

in religious liberty. Accordingly, the initial laws for the colony granted religious freedom to all theists, providing that anyone who would acknowledge the one Almighty and eternal God, to be the Creator, Upholder and Ruler of the world

could not be molested or prejudiced for their religious persuasion, or practice

or compelled, at any time, to frequent or maintain any religious worship, place or ministry whatever.

Although the diverse religious groups in Pennsylvania had social and political disagreements, they did not face persecution from the government for their religious beliefs alone, as they did elsewhere. While this made Pennsylvania unusually tolerant for the era, the colony still limited office-holding to Christians, forbade work on the Sabbath, and prohibited a variety of offences against God

such as swearing, drunkenness, and fornication.

Virginia and Religious Freedom

Virginia, which initially established the Church of England as the church of the colony, began to provide greater religious liberty in the years leading up to the adoption of the Constitution. Toward the end of the colonial period, some Virginia leaders began to look to Pennsylvania as a model for liberty, expressing distaste for Virginia’s state-sponsored religious establishment. By the time Virginia adopted its first state constitution in 1776, it provided that all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience.

Notwithstanding this new constitutional protection for the free exercise of religion, the Church of England remained Virginia’s legally established church. There was significant debate over the next decade about whether the state could or should impose a general assessment to support religion, or whether financial support would instead become voluntary.

In 1779, Jefferson introduced his Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom in the Virginia Assembly. Considered by many to be the forerunner of the First Amendment’s Religion Clauses, the bill was a sweeping statement for religious freedom and against state establishment of religion. Among other provisions, it stated that compelled financial support for churches and religious test oaths infringed individual liberty and corrupted religion. It further provided that allowing the civil magistrate to intrude his powers into the field of opinion . . . at once destroys all religious liberty.

Accordingly, the bill would have prevented Virginia from compelling anyone to frequent or support any religious worship

or otherwise burdening a person on account of his religious opinions or belief.

The bill was not adopted in that legislative session.

By contrast, later in 1779, the Assembly considered—but also rejected—a bill that would have established the Christian Religion

as the state’s official religion, required recognized churches to subscribe to certain beliefs, and assessed ministerial taxes. In 1784, Patrick Henry, who had opposed Jefferson’s Statute for Religious Freedom, introduced A Bill Establishing a Provision for Teachers of the Christian Religion. The law proposed a general assessment: taxpayers could direct the funds to the society of Christians

of their choice, and any nondesignated funds would be used for the encouragement of seminaries of learning

in the state.

While the bill creating an assessment for Christian teachers was being considered, James Madison wrote and circulated his Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, which contributed significantly to the bill’s defeat. Madison’s Memorial and Remonstrance claimed that the right to free exercise of religion was unalienable,

and that religion was wholly exempt

from the cognizance

of civil society. He asserted the bill violated fundamental principles of equality and departed from America’s generous policy

of religious freedom for the previously persecuted and oppressed.

Other opponents of the assessment raised concerns about the rights of non-Christians, a position that was still somewhat uncommon in the colonies at that time. Following this public opposition to Henry’s bill, Madison reintroduced Jefferson’s bill for establishing religious freedom. The Statute for Religious Freedom was enacted in 1786, finally disestablishing religion in the state.

Although Virginia’s experience does not represent the full picture of the early American experience with religious liberty, it helped set the stage for the adoption of the Religion Clauses. While Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, and (eventually) Virginia moved towards greater religious freedom, other states—and some within those states—continued to support state establishments and a more limited view of religious liberty.

Continental Congresses

The Continental Congresses of 1784–1789 addressed a number of issues relating to religion. In some instances, the Congresses’ work reflected the ongoing debates and shifting norms relating to church and state.

One of the grievances that the First Continental Congress identified in its 1774 Declaration and Resolves

addressed to Great Britain was the Quebec Act. The congressional resolution described this Act as establishing the Roman Catholic religion

in Quebec, a province which was expanded to include parts of the modern Midwest. On its face, the Quebec Act did not establish a religion in the sense of requiring adherence or compelling support. Instead, it stated that Roman Catholic citizens in the province may have, hold, and enjoy, the free Exercise of the Religion of the Church of Rome, subject to the King’s Supremacy.

The colonists saw this parliamentary sanction for the Catholic Church in the expanded territory, albeit limited, as a threat. Nevertheless, only about two weeks after adopting the Declaration and Resolves, the Continental Congress wrote a letter to the Inhabitants of the Province of Quebec,

arguing that Great Britain had violated their rights by altering the province’s government and making religious liberty for Catholics a matter of the King’s grace. The letter stated that the Quebec Act’s guarantee of liberty of conscience in . . . religion

was a poor substitute for the God-given rights the province had been denied, for the English version of the right was a precarious

one subject to arbitrary alterations.

These somewhat contradictory stances likely reflected political considerations.

Members of the First Continental Congress also faced appeals for freedom of conscience from within their own territory. Notably, a group of Massachusetts Baptists complained of persecution to delegates of the Continental Congress in 1774. John Adams, in his diary, wrote that he was indignant . . . at seeing [his] State and her Delegates thus summoned before a self created Trybunal.

According to Adams’s account, one Pennsylvanian asserted that New England’s stance on Liberty of Conscience

was standing in the way of forming a Union of the Colonies.

The dissenters’ primary grievances seemed to be taxes for the support of the established churches. The Baptists objected to the tax on grounds of conscience. In response, John and Samuel Adams apparently argued that Massachusetts had the most mild and equitable Establishment of

-but in resisting any commitment to further change, John Adams reportedly said that the objectors might as well expect a change in the solar system, as to expect [Massachusetts] would give up their establishment.

In other matters, the Continental Congress recognized and seemed to support religion. As the Supreme Court has noted, the Continental Congress, beginning in 1774, adopted the traditional procedure of opening its sessions with a prayer offered by a paid chaplain.

According to a contemporaneous account from John Adams, there was some opposition to the first motion to open a session with prayer given the religious diversity of the representatives, until Samuel Adams said he was no Bigot, and could hear a Prayer

from someone of another faith. The Continental Congress also, for example, occasionally declared days of fasting and thanksgiving, and voted to import Bibles for distribution, although it never appropriated the funds for this latter activity.

In contrast, the Second Continental Congress recognized and attempted to accommodate pacifists during the Revolutionary War, stating that Congress intended no violence to their consciences

and asking pacifists to contribute by doing only what they could consistently with their religious principles.

The Northwest Ordinance, adopted by the Confederation Congress in 1787, provided that no person in the territory could be molested on account of his mode of worship or religious sentiments

so long as he was acting in a peaceable and orderly manner.

Furthermore, in 1785, the Confederation Congress rejected a proposal that would have set aside lots in the western territory for the support of religion, with James Madison saying the provision smell[ed] . . . of an antiquated Bigotry.

Overall, the roots of both the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause and the tension between them are evident in the period immediately prior to ratification of the Constitution. While there was some movement towards greater religious liberty and separation of church and state, continued support for religious activity was seen as a basic part of the fabric of society. Even in protecting modes of worship in the territories, the Northwest Ordinance provided that religion, morality, and knowledge

were necessary to good government

and should be encouraged.

Constitutional Convention, Ratification, and the Bill of Rights

The Constitution adopted by the Constitutional Convention in 1787 was largely silent on matters of religion. Nonetheless, matters of religious freedom remained on the Founder’s minds. By 1787, a number of states had adopted constitutions containing some protections for religious freedom-though not all were as broad in scope as the ratified First Amendment. Some state constitutions seemingly limited protections for religious freedom to certain types of believers. Furthermore, as discussed elsewhere, some of those states still supported religious establishments, even as other constitutional provisions limited some aspects of state establishments. North Carolina’s constitution, for example, granted freedom of conscience and forbade an establishment of any one religious church or denomination in this State, in preference to any other,

but further provided that the constitution did not exempt preachers of treasonable or seditious discourses, from legal trial and punishment.

During the debates over ratifying the Constitution, both proponents and opponents argued for the addition of a bill of rights, frequently citing religious freedom as one of the rights that should be expressly protected. Seven states considered amendments expressly protecting religious freedom, and four states ratified the Constitution only after officially recommending such amendments. Virginia, for example, proposed an amendment stating that all men have an equal, natural and unalienable right to the free exercise of religion according to the dictates of conscience, and . . . no particular religious sect or society ought to be favored or established by Law in preference to others.

James Madison, a key figure in the framing and adoption of the Constitution and the First Amendment, initially considered a bill of rights unnecessary. Among his objections to such an enumeration, he was concerned that express declarations of some of the most essential rights

would be stated too narrowly. Focusing specifically on the rights of Conscience,

he noted that some states wanted to deny equal rights to non-Christians, suggesting any public definition of religious freedom would be too narrow. Madison, however, was ultimately persuaded to introduce the amendments that would become the Bill of Rights.

On June 8, 1789, Madison introduced a proposed constitutional amendment in the House of Representatives which read:

The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext, infringed.He further proposed an amendment that expressly prohibited states fromviolat[ing] the equal rights of conscience.Explaining this second provision, Madison believedevery Government should be disarmed of powers which trench upon those particular rights,and wrote thatState Governments are as liable to attack these invaluable privileges as the General Government is.

On August 15, the House considered a version of the amendment that read: no religion shall be established by law, nor shall the equal rights of conscience be infringed.

Debate revealed differences of opinion on what such an amendment should accomplish, but some Members expressed concern that the amendment would unduly prohibit government support for religion-even by the states-and thereby abolish religion altogether. Two days later, the House considered the amendment providing that no State shall infringe the equal rights of conscience,

along with other rights. Madison conceived this to be the most valuable amendment in the whole list,

again arguing it was necessary to prevent both state and federal governments from infringing these essential rights.

Ultimately, the version passed by the House on August 24 read:

Congress shall make no law establishing religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; nor shall the rights of conscience be infringed.The House also passed the amendment providing that[n]o state shall infringe . . . the rights of conscience.

Debate in the Senate was not recorded, but on September 3, 1789, the Senate considered the constitutional amendments adopted by the House. The Senate adopted amendments rewriting the first provision to read: Congress shall make no law establishing one religious sect or society in preference to others.

On September 9, the Senate combined the religion amendments with the other rights that would ultimately be part of the First Amendment into a provision reading:

Congress shall make no law establishing articles of faith or a mode of worship, or prohibiting the free exercise of religion, or abridging the freedom of speech . . . .This version was adopted and sent to the House the same day. The House amendment guaranteeing the rights of conscience against the states was not approved by the Senate.

A joint committee was appointed to resolve the differences between the chambers, and although there is no surviving record of the committee debate, on September 24, 1789, it reported the text that would become the First Amendment:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof of speech . . . .On December 15, 1791, this language was ratified by the requisite number of states.

Early Interpretations of the Religion Clauses

Even after the First Amendment was ratified and the Founders almost universally embraced the general principle of liberty of conscience, significant disagreement remained as to the scope of the prohibition on establishment and the protections of free exercise.

At the time of the Revolution, the majority of the states retained at least some elements of religious establishments, including requiring church attendance, collecting tithes, and burdening the rights of religious dissenters. States did not become subject to the First Amendment when it was adopted in 1791, and accordingly had more leeway to regulate on the subject of religion, but the movement to disestablish official state religions nonetheless continued to gain support as views changed about the appropriate role of church and state. In 1791, one prominent minister, arguing against state-established religions, noted that by that time, most states had no legal force used about religion, in directing its course, or supporting its preachers.

Seven disestablishments of state sanctioned religions occurred after the First Amendment’s adoption, with the last, Massachusetts’s, occurring in 1833. This gradual disestablishment was accompanied in many cases by civil regulation of the corporate forms and property rights of the churches, eventually leading to questions about whether such regulation was contrary to constitutional guarantees of religious liberty.

Maryland’s experience serves as one example of this trend. The state’s 1776 constitution extended legal toleration to all Christian sects but required officeholders to declare Christian belief and authorized the state legislature to impose a general tax for the support of the Christian religion.

Maryland had thus abandoned its Church of England establishment but continued to generally support Christianity and adopted laws regulating the Anglican church. However, a 1784 bill that would have levied a tax for the support of ministers was defeated. The bill’s opponents argued that it would have preferred certain sects, impermissibly set up the legislature as the judge of acceptable worship, and set up a confrontation with sects such as Quakers that would refuse to pay. In 1810, Maryland amended its constitution by providing that it would no longer be lawful to tax citizens to support religion. However, the state’s constitution continued to require officeholders to declare a general belief in existence of God until 1961, when the provision was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

These diverse and shifting views over religion were also reflected at the federal level. For example, early Congresses employed chaplains and supported proclamations for national days of thanksgiving. By the 1800s, however, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson had seemingly changed their mind on the propriety of government prayer. Toward the end of his presidency, Jefferson explained that he would not recommend a day of prayer because even voluntary language suggested an authority over religion that, in his view, the government did not possess. James Madison eventually concluded that establishing a congressional chaplain was a palpable violation

of the Constitution. Further, although as President, he had issued proclamations for national days of prayer and thanksgiving, Madison believed these religious proclamations were similarly problematic. Madison stated that he had issued the proclamations only at Congress’s request, and had used language intended to deaden as much as possible any claim of political right to enjoin religious observances

by referring to the voluntary compliance of individuals.

Another example of the debate over the separation of church and state involved an 1811 bill that would have incorporated the Protestant Episcopal Church in the District of Columbia. Then-President Madison vetoed the bill, stating that it violated the Establishment Clause by enacting rules for the church’s organization and polity,

giving a legal force and sanction

to certain articles of church administration and actions. The House of Representatives failed to override the veto. In the debate preceding that vote, some proponents of the bill argued that it did not violate the Establishment Clause because it did not establish a National Church such as the Church of England. Another Member argued that if the debated bill infringed the Constitution, then Congress had similarly violated the Constitution by appointing and paying chaplains.

Other debates during this period focused on whether the United States could be considered a Christian nation. In the 1797 Treaty of Tripoli, the government assured the Muslim state of Tripoli that because the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian Religion, . . . no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.

Beginning in the nineteenth century, Congress failed to adopt a variety of proposals that would have amended the Constitution to describe the United States as a Christian nation, or the federal government as a Christian one.

Originally published by the United States Library of Congress to the public domain.