A nation born in rebellion against centralized authority has repeatedly turned to its presidents to enforce order when unity was threatened.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Tension Between Liberty and Order

The American republic was born with a paradox at its core. The Constitution granted the federal government authority to maintain order, but the very memory of monarchy and centralized coercion bred deep suspicion of federal intrusion into daily life. Nowhere was this paradox sharper than in questions of policing. The states retained general “police powers” under the Tenth Amendment, yet crises forced presidents to act in ways that blurred the boundary between federal authority and local enforcement.

Washington, Adams, Jackson, and Lincoln each faced moments when the survival of the Union seemed to hang on whether the federal government could assert its power against resistance. Their responses, ranging from the mobilization of militias to the suspension of habeas corpus, reveal the uneasy trajectory by which federal authority expanded in the name of law. These episodes also underscore how presidents weaponized legality, not unlike ancient rulers, to consolidate their authority under the guise of public order.

George Washington and the Whiskey Rebellion

In 1794, farmers in western Pennsylvania violently resisted the federal excise tax on whiskey. Local sheriffs proved unable or unwilling to enforce the unpopular law, and open defiance spread into mob action. Washington responded by invoking the Militia Act of 1792, calling out nearly 13,000 troops from several states to march westward.1 It was the first and only time a sitting president personally led troops into the field.

The suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion is often remembered as a triumph of federal authority, establishing that laws enacted by Congress would be enforced. Yet the episode is also telling for what it reveals about policing in the early republic. With no federal police force and a skeletal U.S. Marshals Service, Washington had to militarize the situation. The reliance on soldiers to enforce tax law blurred the line between civil order and martial power. It set a precedent that in moments of domestic crisis, presidents could federalize enforcement not by commandeering local police but by overwhelming them with military force.

The event left a lasting imprint on political culture. To Federalists, it proved the stability of the Constitution. To Jeffersonian critics, it revealed the dangers of centralized coercion disguised as legality. Washington may not have federalized police powers in the modern sense, but his actions showed how fragile the boundary was between civil authority and military enforcement.

John Adams and the Alien and Sedition Acts

If Washington’s test was rebellion in the field, Adams’ was dissent in print. In 1798, amid tensions with France, the Federalist Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, granting the executive sweeping powers to detain non-citizens and criminalize criticism of the government.2 For the first time, federal authority reached deeply into the realm of speech and press, matters traditionally shielded by the Bill of Rights.

The enforcement of these acts depended upon federal marshals and compliant judges. Local police remained in state hands, but Adams effectively created a system where political opposition could be branded as unlawful. Republican editors found themselves fined or jailed for “seditious libel.” The federal government, lacking a police force of its own, nonetheless extended its power by weaponizing existing structures of enforcement in service of partisan ends.

Unlike Washington, who relied on troops in the open field, Adams wielded the law itself as an instrument of political suppression. The Alien and Sedition Acts did not last; they expired or were repealed within a few years, but they established a troubling precedent: that presidents might harness federal authority not only against armed insurrection but against dissenting voices. The line between law enforcement and political control grew perilously thin.

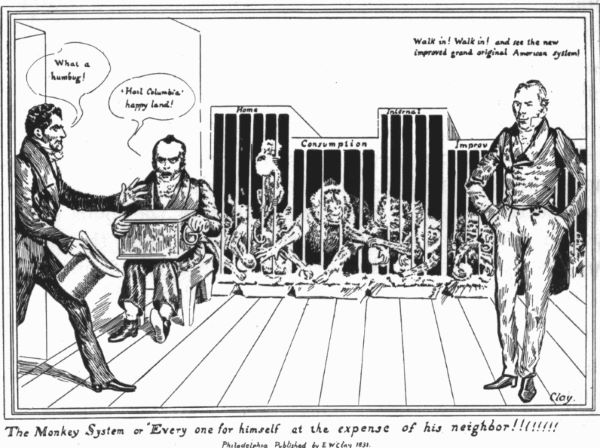

Andrew Jackson and the Nullification Crisis

In the 1830s, Andrew Jackson confronted South Carolina’s nullification of the federal tariff. Unlike the Whiskey Rebellion, this was not a mob of farmers but a state government openly declaring its right to defy federal law. Jackson, though a champion of states’ rights in rhetoric, refused to tolerate defiance when the authority of the Union was at stake.

Jackson secured passage of the Force Bill in 1833, authorizing him to use the army and navy to enforce tariff collection.3 He simultaneously prepared federal customs officers for direct confrontation in South Carolina ports. Although compromise eventually defused the crisis, the episode demonstrated how federal power could be projected into local enforcement when state authorities refused cooperation.

The Nullification Crisis reveals the complexity of Jackson’s legacy. He portrayed himself as the tribune of the common man, hostile to centralization, yet in practice he was willing to expand federal enforcement to prevent secession. His willingness to invoke military power against a state foreshadowed the harsher federal measures that Lincoln would later embrace. Jackson did not federalize local police, but he showed how presidents could stretch executive authority to enforce compliance when states defied the law.

Abraham Lincoln and the Suspension of Habeas Corpus

Lincoln’s presidency marked the decisive rupture. Confronted with secession and civil war, he assumed powers that far exceeded his predecessors. Most famously, he suspended habeas corpus, allowing federal authorities to detain individuals without trial.4 In border states such as Maryland, federal troops arrested local officials suspected of Confederate sympathies, effectively replacing civil policing with military occupation.

Here, the federal government did more than enforce law; it displaced local authority entirely. Federal troops guarded railroads, censored newspapers, and detained political dissidents. In some areas, the writ of habeas corpus remained suspended for years. Lincoln defended these actions as necessary for the survival of the Union, insisting that extraordinary times demanded extraordinary measures.

The suspension of habeas corpus raises difficult questions about the nature of legality. Was Lincoln weaponizing the Constitution to suppress dissent, or was he preserving the nation’s legal order by temporarily suspending it? The paradox is stark. By bypassing courts and local police, he strengthened the federal hand in ways that permanently altered the balance of authority. His measures created the closest approximation in early American history to the federalization of policing powers, albeit under the extreme conditions of civil war.

Patterns and Legacies of Federal Authority

From Washington to Lincoln, four patterns emerge. First, crises of resistance drove presidential action. None of these men sought to federalize enforcement in ordinary times, but all acted decisively when defiance threatened federal authority. Second, military force became the default instrument in the absence of a national police. Third, presidents increasingly learned to wield legality itself (through statutes, courts, or suspended rights) as a means of control. Finally, each episode deepened the precedent that the federal government could step into the domain of policing when survival demanded it.

These cases reveal that the line between federal and state authority was never as rigid as theory suggested. The Constitution left police powers to the states, yet presidents from Washington to Lincoln demonstrated a feeling that law and order were too vital to be left entirely in local hands. Each crisis eroded the firewall, leaving a legacy of expanded federal authority that later presidents would inherit.

Conclusion: Liberty, Order, and the Federal Dilemma

The early republic was haunted by the specter of centralized coercion. Washington’s march into Pennsylvania, Adams’ prosecutions of dissenters, Jackson’s threats against South Carolina, and Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus each sparked fierce debate over liberty and order. Yet in every case, the federal government emerged stronger.

To trace this trajectory is to recognize the irony of American constitutional development. A nation born in rebellion against centralized authority has repeatedly turned to its presidents to enforce order when unity was threatened. The federalization of policing in the modern sense did not exist, but the seeds were planted. Washington, Adams, Jackson, and Lincoln each discovered that the machinery of law could be adapted, stretched, and weaponized when survival required it. That legacy, born of crisis, remains embedded in the American state.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Thomas P. Slaughter, The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 195–203.

- James Morton Smith, Freedom’s Fetters: The Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1956), 142–158.

- Richard E. Ellis, The Union at Risk: Jacksonian Democracy, States’ Rights, and the Nullification Crisis (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 211–225.

- Mark E. Neely Jr., The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 24–39.

Bibliography

- Ellis, Richard E. The Union at Risk: Jacksonian Democracy, States’ Rights, and the Nullification Crisis. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Neely, Mark E., Jr. The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Slaughter, Thomas P. The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Smith, James Morton. Freedom’s Fetters: The Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1956.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.