The German case shows that truth alone is insufficient if it is not paired with ethical judgment and selective validation.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Defeat, Responsibility, and the Danger of False Redemption

Germany’s defeat in 1945 represented not merely the collapse of a military campaign but the disintegration of a political and moral order built on systematic criminality. The unconditional surrender of the Third Reich marked the end of a regime whose authority depended on mass violence, racial ideology, and the destruction of democratic institutions. Unlike conventional defeats that invite narratives of tragedy or heroic resistance, Germany’s collapse exposed crimes on a scale that foreclosed any legitimate claim to moral equivalence. The central problem that followed was not how to console a wounded national pride, but how to integrate catastrophic guilt into a democratic future without permitting defeat to be reframed as virtue.

Memory became the central terrain on which this problem was addressed. Postwar Germany faced a dual imperative: to preserve the truth of Nazi crimes exhaustively and to prevent that truth from being distorted into narratives of suffering that might obscure responsibility. Forgetting was impossible, but remembering carried its own risks. Selective memory could soften culpability, while sentimental remembrance might invite sympathy for perpetrators rather than victims. The danger lay in false redemption, the transformation of defeat into a story of bravery, sacrifice, or national martyrdom that would undermine the ethical foundations of the new democratic order.

The German response was distinctive in its refusal to separate historical documentation from moral judgment. Nazi crimes were recorded in trials, archives, museums, and educational curricula not as episodes of excess within an otherwise legitimate state, but as the defining reality of the regime itself. Memory was institutionalized as an instrument of accountability rather than reconciliation. This approach rejected the notion that time or defeat could cleanse responsibility, insisting instead that democratic legitimacy depended on the unflinching preservation of truth paired with the categorical denial of honor.

Post-1945 Germany demonstrates how democracies can survive catastrophic defeat by remembering truthfully and honoring selectively. Memory was preserved precisely to prevent glorification, not to soften judgment. By documenting crimes exhaustively while refusing any form of civic honor for the defeated regime, Germany constructed a moral boundary that stabilized its democratic reconstruction. The postwar settlement reveals that remembrance does not require redemption, and that the refusal to honor a criminal past is not an act of vengeance but a condition of democratic survival.

The Nature of the Defeat in 1945

Germany’s defeat differed fundamentally from conventional military loss because it entailed the collapse of a regime whose legitimacy was inseparable from systematic crime. The unconditional surrender did not merely mark the failure of a war effort or the exhaustion of national resources, but the total delegitimation of a political order that had defined itself through racial hierarchy, mass murder, and the annihilation of democratic norms. The exposure of concentration camps, the documentation of genocide, and the scale of civilian devastation made it impossible to frame defeat as misfortune, miscalculation, or strategic error. What ended in 1945 was not simply a government or a ruling elite, but a moral claim to rule that had been built upon violence as policy. Defeat functioned as a verdict, rendered not only by military force but by the evidence of the regime’s own actions.

This defeat was comprehensive in both territorial and institutional terms. The Third Reich ceased to exist as a sovereign entity, its leadership removed through death, capture, or trial, and its governing structures dismantled by occupying powers. Unlike earlier German defeats, which had left space for myths of betrayal or unfinished struggle, the events of 1945 foreclosed ambiguity. The state that had prosecuted the war was revealed, in its own records and actions, as a criminal enterprise. Defeat functioned as exposure rather than humiliation, stripping the regime of any remaining narrative defenses.

The nature of the surrender reinforced this finality. Germany did not negotiate terms that might have preserved honor, continuity, or symbolic autonomy. Unconditional surrender eliminated the possibility of portraying the outcome as honorable resistance against overwhelming odds or as the result of diplomatic injustice. The absence of a negotiated settlement mattered symbolically as well as politically. There was no treaty that could later be reframed as unfair, no imposed condition that could be mythologized as national betrayal, and no surviving regime that could claim moral survival. Defeat attached responsibility directly and unmistakably to the political order that had produced catastrophe, leaving no space for alternative narratives of loss.

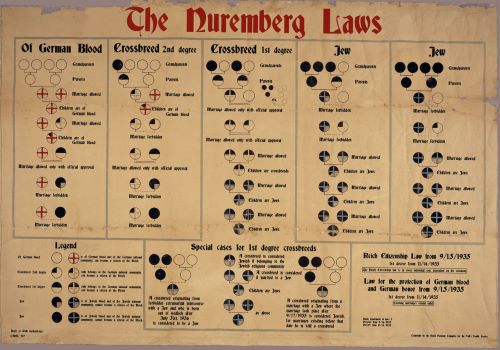

Equally significant was the international framing of Germany’s collapse. The Allied response emphasized accountability rather than reconciliation, insisting that crimes be named, documented, and judged. The Nuremberg Trials established a precedent that linked defeat directly to legal and moral responsibility. The defeated were not treated as tragic soldiers of a lost cause, but as agents within a system of organized atrocity. This framing denied the possibility that defeat could be separated from guilt or that loss could be redeemed through appeals to courage or sacrifice.

Germany’s loss became a boundary rather than a wound. It marked the end of a political experiment whose failure was intrinsic rather than contingent, structural rather than accidental. There was no space for narratives of noble defeat, shared suffering, or moral equivalence because the regime’s actions had already defined the meaning of its collapse. The nature of the defeat in 1945 shaped all subsequent memory practices by establishing the terms under which the past could be addressed. Remembrance would serve accountability rather than consolation, and history would be preserved not to honor what was lost, but to prevent its return.

Documentation without Rehabilitation

In the immediate aftermath of 1945, Germany embarked on an unprecedented project of documenting the crimes of the defeated regime, one that extended far beyond the requirements of postwar justice. This effort was not confined to establishing culpability for a limited number of leaders, nor was it oriented toward drawing a line under the past. Instead, documentation became a long-term democratic obligation. Archives were assembled, preserved, and opened; evidence was cataloged with meticulous care; and records of atrocity were treated as public property rather than as material to be sealed or selectively remembered. The goal was not reconciliation through forgetting, nor closure through symbolic gestures, but the preservation of truth in its most unvarnished form. Documentation served as a safeguard against denial and distortion, anchoring memory in verifiable record rather than myth, sentiment, or nationalist reinterpretation.

The Nuremberg Trials set the tone for this approach. By prosecuting leading figures of the Nazi regime in an international forum, the trials established a public, legal account of criminal responsibility that linked individual actions to systemic policy. Testimony, documents, and visual evidence exposed the bureaucratic nature of atrocity and denied the defense of ignorance or inevitability. Crucially, the trials did not frame defendants as tragic actors trapped by circumstance. They were treated as accountable agents within a criminal state, ensuring that defeat could not be reframed as honorable resistance or misunderstood sacrifice.

Beyond the courtroom, the accumulation and preservation of archives reinforced this commitment to truth without redemption. Government records, military correspondence, administrative files, and party documentation were systematically collected and made accessible to scholars, journalists, and the public. This openness allowed sustained examination of how crimes were planned, authorized, and executed across multiple levels of governance. By exposing the routine and procedural nature of mass violence, archival transparency prevented the emergence of narratives that might isolate guilt to a few individuals or transform collective responsibility into abstract tragedy. Documentation functioned as a structural barrier against romantic reinterpretation, ensuring that memory remained anchored to evidence rather than to emotion or selective remembrance.

Educational policy further embedded this discipline of memory. Schools and universities incorporated the history of National Socialism and the Holocaust into curricula as foundational knowledge rather than marginal topic. Students encountered the regime not as a story of national tragedy but as a case study in democratic collapse and moral failure. The emphasis on responsibility over victimhood reinforced the principle that remembrance existed to prevent repetition, not to generate sympathy for the defeated.

These practices constituted a model of remembrance without rehabilitation. Documentation was exhaustive precisely because it denied the defeated regime any claim to dignity or moral recovery. Memory was preserved to expose, to teach, and to warn, not to redeem. In this framework, the past remained present as obligation rather than inheritance, and defeat remained inseparable from responsibility.

Memorial Culture and the Refusal of Honor

Postwar Germany’s memorial culture developed around a deliberate rejection of heroic representation and national glorification, marking a sharp break from conventional practices of war remembrance. Rather than offering symbols of valor, sacrifice, or collective endurance, commemorative efforts after 1945 were designed to unsettle and to instruct. This approach reflected an explicit recognition that traditional forms of honor would risk transforming memory into moral consolation. In a society rebuilding itself as a democracy after unprecedented crimes, remembrance could not function as affirmation. Memorials were conceived as sites of confrontation, insisting that the past be encountered as a problem to be reckoned with rather than a legacy to be redeemed. Memory was structured to resist pride, nostalgia, and the comforting narratives that often accompany national defeat.

The absence of monuments honoring German soldiers or leaders of the Nazi era was not an oversight but a foundational principle. No statues commemorate defenders of the Reich, no public squares are named for its generals, and no state-sponsored memorials frame defeat as bravery under impossible circumstances. The refusal to monumentalize perpetrators or combatants ensured that public space would not become a site of symbolic redemption. Honor, understood as civic endorsement, was categorically denied to the defeated regime and those who served it.

Instead, German memorials foreground victims and crimes rather than national experience. Sites such as former concentration camps, deportation points, and execution grounds were preserved as places of documentation and confrontation. These spaces resist aesthetic comfort. They do not invite admiration or patriotic identification but impose historical responsibility. Memorial architecture emphasizes disruption, fragmentation, and disorientation, signaling that the past being remembered cannot be reconciled through narrative closure or moral equivalence.

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin exemplifies this approach with particular clarity. Its abstract field of stelae rejects figurative representation and heroic symbolism, offering no central figure, narrative arc, or interpretive resolution. Visitors move through a disorienting landscape that resists mastery or comprehension, mirroring the ethical rupture created by genocide. The memorial does not narrate German suffering or national loss, nor does it provide a consoling story of redemption. Instead, it creates an experience of absence, instability, and unease. Memory here is not didactic in the traditional sense but experiential, forcing confrontation with loss without providing interpretive escape. The design ensures that remembrance cannot be converted into admiration or pity for the defeated but remains fixed on the victims and the crime itself.

This memorial culture also reflects a refusal to allow time to soften judgment. Unlike societies that gradually rehabilitate defeated causes through distance and nostalgia, Germany’s commemorative practices insist on the persistence of moral asymmetry. The passage of generations has not produced monuments that reinterpret defeat as sacrifice or frame perpetrators as victims of historical forces beyond their control. Memory remains anchored to responsibility, resisting the temptation to recast catastrophe as tragedy divorced from agency.

Germany constructed a civic landscape in which remembrance operates as restraint rather than reconciliation. Memorials do not redeem the past; they discipline it by fixing moral boundaries within public space. By commemorating victims without honoring perpetrators, and by preserving sites of crime without aestheticizing them, Germany ensured that memory would function as democratic vigilance rather than national consolation. The refusal of honor was not an erasure of history but its moral clarification, reinforcing the principle that some defeats must remain dishonorable if democracy is to endure.

Law, Prohibition, and Moral Boundary Enforcement

Alongside memorial practice and documentation, postwar Germany enforced its discipline of memory through law, treating legal boundaries as integral to democratic reconstruction rather than as auxiliary safeguards. Legal prohibition functioned as a moral boundary as much as a security measure, signaling that certain ideologies were not merely defeated but permanently disqualified. The democratic order that emerged after 1945 did not regard Nazism as one viewpoint among others or as a historical error open to neutral expression. It was understood as a criminal system whose symbols, rhetoric, and organizational forms retained the capacity to destabilize democratic life. Law became a means of translating historical judgment into enforceable civic norms, ensuring that remembrance was inseparable from restraint.

Central to this framework was the categorical ban on Nazi symbols, insignia, and propaganda. Swastikas, SS runes, and other emblems of the regime were prohibited from public display not because they were merely offensive or emotionally charged, but because they functioned as instruments of political reactivation. Symbols condense ideology into immediate recognition, allowing allegiance to be signaled without argument or explanation. In the context of Germany’s past, such symbols could not be treated as inert references. By criminalizing their use, the state severed the visual and symbolic continuity between the Nazi regime and the present, denying defeated ideology the ability to occupy public space or reclaim visibility as identity.

Speech restrictions further reinforced this boundary. Holocaust denial, trivialization, and the glorification of the Nazi regime were criminalized as attacks on democratic order rather than as protected expression. These laws did not seek to police historical inquiry, which remained extensive, contested, and academically rigorous. Instead, they targeted the deliberate distortion of history for political ends. Denial was understood as an attempt to erase victims in order to rehabilitate perpetrators, transforming falsification into a form of ideological aggression. Law operated not against debate or scholarship, but against the use of historical falsehood as a tool for reclaiming legitimacy.

These prohibitions reflected a broader understanding of democracy as a system that requires enforced limits to survive. Postwar Germany rejected the assumption that unrestricted tolerance could coexist with democratic stability in the shadow of its own history. The constitutional order asserted the right to defend itself against movements that sought to undermine it from within, drawing explicit lessons from the failures of the Weimar Republic. Moral asymmetry was preserved not only through memory and education but through enforceable constraints that marked Nazism as permanently excluded from civic participation. Democracy, in this framework, was not neutral toward its enemies, but conscious of the conditions required for its preservation.

Through law, Germany transformed the lesson of defeat into a durable institutional safeguard. Prohibition did not erase the past or prevent its study; it prevented its reactivation as honor, identity, or political claim. Memory was preserved exhaustively, but legitimacy was policed rigorously. In this legal architecture, the refusal of glorification became an enforceable principle rather than a matter of cultural preference, ensuring that democratic remembrance remained inseparable from democratic survival.

Remembering Truthfully without Creating Moral Equivalence

A central challenge in postwar German memory culture was how to preserve exhaustive truth without sliding into moral equivalence. Remembering the past in full detail risked, for some observers, reopening questions of national suffering that might blur responsibility. The German response rejected this concern by insisting that truthful remembrance and moral judgment were not opposing obligations. Accuracy did not require neutrality, and completeness did not demand sympathy for perpetrators. Memory could be expansive while remaining ethically asymmetric.

This approach required a deliberate rejection of narratives that framed German defeat primarily as tragedy. While acknowledging the immense destruction experienced by German civilians, postwar discourse resisted placing that suffering on the same moral plane as the crimes of the regime. Civilian loss was recognized as real and devastating, but it was consistently contextualized as consequence rather than counterbalance. The distinction mattered profoundly. To present defeat as shared tragedy would have implied equivalence between those who suffered because of the regime’s actions and those who suffered under its policies of extermination and conquest. German remembrance instead maintained a hierarchy of responsibility, ensuring that grief did not displace culpability and that sympathy did not become a substitute for judgment.

Public debate over victimhood further illustrates this discipline of memory. Discussions of German expulsion from Eastern Europe, wartime bombing, and postwar deprivation were not suppressed or denied entry into historical discourse. However, they were framed within a broader narrative of causation that traced these experiences back to the regime’s decisions and crimes. Suffering was acknowledged without being isolated from its origins. By situating German loss within a chain of responsibility, remembrance avoided the inversion that would transform perpetrators or beneficiaries of the regime into primary victims of history. Truthful memory became contextual memory, one that resisted selective emphasis and prevented emotional identification from eroding moral clarity.

This refusal of moral equivalence also shaped Germany’s engagement with its own resistance movements. Acts of opposition to Nazism were recognized but carefully bounded. Resisters were honored as exceptions, not as representatives of a morally intact nation overwhelmed by tyranny. Their commemoration reinforced responsibility rather than diluted it. By emphasizing the rarity and danger of resistance, Germany avoided constructing a redemptive narrative in which isolated acts of courage could redeem systemic complicity or erase widespread participation.

International comparison further reinforced this stance. Germany did not present itself as uniquely victimized by the war’s outcome, nor did it claim moral parity with those it had attacked. Instead, remembrance was oriented outward, acknowledging responsibility to victims beyond national borders. This outward orientation countered the inward turn common in post-defeat narratives, in which nations recast themselves as misunderstood, punished excessively, or morally equivalent to their enemies. German memory culture resisted such self-exculpatory framing by situating national experience within a transnational moral landscape shaped by aggression and atrocity.

Germany demonstrated that democratic remembrance depends on selective honor rather than selective memory. Truth was preserved in full, but honor was granted sparingly and purposefully, with clear moral intent. By refusing to equate suffering with innocence or defeat with virtue, postwar Germany stabilized its historical narrative against erosion by sentiment or fatigue. Memory functioned not as a balm for national self-regard but as a continual ethical demand, requiring acknowledgment rather than absolution. Remembering truthfully without creating moral equivalence ensured that defeat could be integrated into democratic identity without being transformed into moral capital, reinforcing the principle that accountability, not consolation, is the foundation of legitimate remembrance.

Conclusion: Democracies Remember Truthfully and Honor Selectively

Germany’s post-1945 reckoning demonstrates that democratic stability does not require forgetting catastrophic pasts, nor does it depend on emotional reconciliation with defeat. Instead, it rests on a disciplined separation between remembrance and honor. By preserving the historical record of Nazi crimes exhaustively while refusing any form of civic glorification, Germany established a moral framework in which memory functioned as accountability rather than consolation. Defeat was integrated into national consciousness without being converted into virtue, ensuring that loss could not be repurposed as moral claim or reframed as tragic heroism. Memory served not to rehabilitate what had failed, but to delimit it permanently, fixing the boundaries of what democratic society could acknowledge without endorsing.

The German case shows that truth alone is insufficient if it is not paired with ethical judgment and selective validation. Documentation, education, and memorialization were effective precisely because they were accompanied by a categorical refusal to dignify the defeated regime or those who served it. Honor was withheld from perpetrators and collaborators, while reserved for victims and, in narrowly defined cases, for resisters whose actions underscored responsibility rather than diluted it. This selectivity was not arbitrary or punitive, but structural. It prevented the erosion of moral boundaries that occurs when sympathy replaces accountability, and it ensured that remembrance reinforced democratic values instead of undermining them through misplaced equivalence or nostalgia.

This approach avoided both suppression and indulgence. Memory was not censored, but it was structured. The past was neither silenced nor sentimentalized. By allowing exhaustive study while enforcing clear limits on commemoration and symbolism, Germany prevented memory from drifting into equivalence or nostalgia. Remembrance became an instrument of democratic vigilance, sustaining awareness of how easily institutions can be corrupted when accountability collapses.

The lesson extends beyond Germany’s specific history. Democracies survive not by honoring all who are remembered, but by remembering in ways that reinforce legitimacy and responsibility. When truth is preserved without honor, defeat can be absorbed without being redeemed. Germany’s postwar settlement illustrates that the refusal to glorify a criminal past is not an obstacle to democratic renewal, but one of its essential conditions.

Bibliography

- Ahonen, Pertti. “Germany and the Aftermath of the Second World War.” The Journal of Modern History 89:2 (2017), 355-387.

- Arieli-Horowitz, Dana. “The Nazi Phantom: German Cities Confronting Their Past.” Germania (2009).

- Art, David. The Politics of the Nazi Past in Germany and Austria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Assmann, Aleida. Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions Avoidances, Media. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Burch-Brown, Joanna. “Is It Wrong to Topple Statues & Rename Schools?” Journal of Political Theory & Philosophy 1 (2017), 59-88.

- Douglas, Lawrence. The Memory of Judgment: Making Law and History in the Trials of the Holocaust. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

- Evans, Richard J. The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- Fulbrook, Mary. German National Identity after the Holocaust. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999.

- Habermas, Jürgen. The New Conservatism. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1989.

- Judt, Tony. Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- Legg, Stephen. “Contesting Monuments: Heritage and Historical Geographies of Inequality, an Introduction.” Journal of Historical Geography 87 (2025), 1-12.

- Mazower, Mark. Dark Continent: Europe’s Twentieth Century. New York: Vintage, 1998.

- Müller, Jan-Werner. Memory and Power in Post-War Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Overy, Richard. The Dictators: Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia. New York: W. W. Norton, 2004.

- Sukovata, Viktoriya. “Demolition of Monuments as a Phenomenon of Culture in Global and Local Contexts: Iconoclasm, ‘New Barbarity’, or a Utopia of Memory?” Studies on National Movements 10 (2022), 44-73.

- Till, Karen E. The New Berlin: Memory, Politics, Place. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

- Young, James E. “The Counter-Monument: Memory against Itself in Germany Today.” Critical Inquiry 18:2 (1992), 267-296.

- —-. The Texture of Memory. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.11.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.