The early colonization of Latin America was a project of monumental violence. It erased civilizations, enslaved millions, and reconfigured entire ecologies.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Imperial Appetite and the Making of a New World

When European ships appeared off the coasts of the Americas in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, they carried more than adventurers. They bore with them the full weight of imperial ambition, religious certitude, and economic hunger. What followed the so-called “discovery” of the Americas was not a moment of encounter so much as a sustained campaign of extraction, redefinition, and devastation. From the earliest phases of colonization in the Caribbean to the sprawling viceroyalties of New Spain and Peru, Latin America became a theater of conquest where the boundaries of empire were drawn with blood, silver, and scripture.

The colonial history of Latin America is often sanitized in textbooks as a tale of heroic exploration and cultural exchange. Yet this narrative fails to account for the systematic exploitation that defined the period – of people, land, and knowledge. The colonization of Latin America was not simply an act of territorial acquisition. It was a reordering of life, where indigenous bodies became labor, landscapes became mines, and belief became weapon. Here I examine the early stages of Spanish and Portuguese colonization, tracing how systems of extraction, religious domination, and racial hierarchy took root, shaping the region’s social, economic, and spiritual architecture for centuries to come.

Conquest and Collapse: From Encounter to Subjugation

The Fall of Empires: Aztec and Inca Resistance and Ruin

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire under Hernán Cortés and the subsequent defeat of the Inca by Francisco Pizarro stand as archetypes of colonial aggression. Both campaigns were marked by a ruthless exploitation of local rivalries, deceptive diplomacy, and staggering violence. Yet the relative speed with which these vast empires fell should not be mistaken for inevitability. The indigenous world did not collapse; it was shattered.

In Tenochtitlán, Cortés capitalized on discontent among Tlaxcalan and other subject peoples who had long resented Aztec tribute demands.1 His campaign relied on alliances as much as firearms. Still, the eventual siege and destruction of the city in 1521 was not a triumph of technology but a sustained act of cultural annihilation. Temples were torn down, disease ran rampant, and the sacred geography of the Mexica was literally paved over.2

In the Andes, Pizarro’s conquest of the Inca unfolded amidst a succession crisis triggered by the civil war between Atahualpa and Huáscar.3 The Spanish arrival inserted itself into an unstable moment, but it transformed that instability into permanent fracture. The capture and execution of Atahualpa in 1533 was emblematic of the Spaniards’ strategy: decapitate the political structure, then assume control of its administrative shell. Yet indigenous resistance persisted for decades in the form of rebellion, withdrawal, and cultural adaptation. The empires did not vanish. They were coerced into ghostly mimicry, their structures absorbed and hollowed out.

Violence as Policy: The Logic of Terror

Conquest was not accidental violence. It was intentional policy. From the Requerimiento, a legalistic declaration of Spanish authority read aloud in Spanish to bewildered indigenous communities, to public massacres and forced relocations, the Spanish approach to colonization assumed native resistance as illegitimate and native sovereignty as void.4 The colonial project relied on making resistance appear irrational and submission natural.

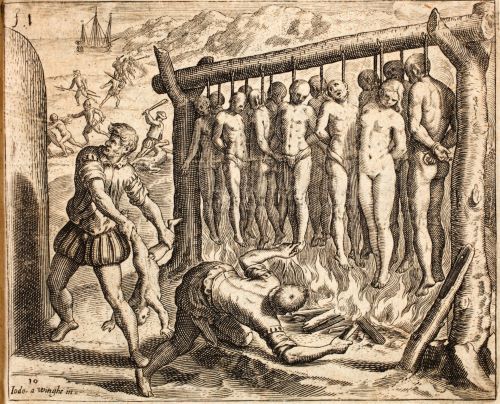

While modern scholars rightly emphasize the agency of indigenous actors and the complexity of cultural hybridity, it is crucial not to minimize the brutality of the initial encounter. Rape, enslavement, and torture were not excesses but standard elements of early colonization. As Bartolomé de las Casas would write in his Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias, the conquest “surpassed in cruelty anything previously known to mankind.”5 His polemic, however stylized, captured a truth that remains difficult to assimilate into national narratives: that empire was not merely expansion but devastation.

Systems of Extraction: Labor, Land, and the Colonial Economy

Encomienda and the Making of Colonial Slavery

In the wake of conquest, the Spanish Crown devised the encomienda system as a means of managing land and labor. In theory, it was a feudal arrangement in which encomenderos were granted the right to indigenous tribute and labor in exchange for Christian instruction and protection. In practice, it was forced labor under another name.6

The encomienda transformed entire indigenous communities into economic units. Labor was extracted through quotas, and failure to meet them resulted in corporal punishment or worse. The supposed paternalism of the system masked its extractive core. Indigenous people became both workers and currency, essential to the wealth of colonists and the function of the colonial state.

Efforts at reform, including the New Laws of 1542 championed by Las Casas, met fierce resistance and limited enforcement.7 The colonists viewed any attempt to curb their access to indigenous labor as an affront to their rights. The colonial legal system, though replete with decrees and royal proclamations, functioned less as a restraint than a justification. Law became a performance of justice that rarely altered the machinery of exploitation.

The Rise of Silver and the Economics of Empire

Nowhere was the colonial economy more visibly extractive than in the silver mines of Zacatecas and Potosí. From the mid-sixteenth century onward, these mines became the lifeblood of the Spanish Empire, flooding the European economy with bullion and transforming global trade. But this silver was paid in blood.

The mita system, inherited from the Incas and repurposed by the Spanish, forced indigenous men into rotational labor in mines under horrific conditions.8 High-altitude exposure, toxic mercury processing, and brutal work rhythms led to staggering mortality rates. The colonial economy depended on a calculus in which life was expendable and metal eternal.

Silver was not merely a commodity. It was a structuring logic. Towns were built around mines, and supply lines stretched from the Andes to Seville. The empire was not held together by royal decree but by the circulation of this wealth and the labor that extracted it. Indigenous survival strategies ranged from flight and sabotage to legal petitioning, but the system remained remarkably durable.

Spiritual Colonization: Conversion, Discipline, and the Production of Souls

Evangelization and the Theater of Conversion

Religious justification was central to the colonial project. The Spanish Crown claimed legitimacy through the twin imperatives of civilization and Christianization. The Franciscans, Dominicans, and Jesuits arrived as soldiers of the spirit, determined to replace idolatry with Catholic orthodoxy.

Evangelization was both a theological and theatrical process. Missionaries staged mass baptisms, destroyed idols, and appropriated sacred spaces for churches. But they also wrote grammars of indigenous languages, trained native catechists, and attempted to translate Christian doctrine into indigenous cosmologies.9 The result was a complex interplay between imposition and syncretism.

Some missionaries, particularly the Jesuits, developed sophisticated approaches to education and conversion, most famously in the reducciones of Paraguay.10 These settlements aimed to isolate indigenous converts from colonial corruption and create ideal Christian communities. Yet even these utopias operated on a logic of discipline and control. Conversion was not a gentle persuasion. It was a reshaping of time, space, and identity.

Saints, Demons, and the Colonial Imagination

Conversion narratives often relied on apocalyptic imagery. Indigenous deities were cast as demons, and resistance to Christianity became evidence of spiritual blindness. In this framework, the colonized were not only exploited bodies but errant souls. This justified not only violence but pedagogical surveillance. Confession, mass attendance, and doctrinal testing became tools of governance.

Yet the indigenous response was never passive. Many communities blended Catholic and pre-Hispanic practices into layered systems of belief. Saints were reimagined as ancestral spirits. Virgin Mary iconography was fused with local goddesses. The Church condemned these practices as heretical, but they revealed the persistence of indigenous cosmologies beneath the surface of imposed piety.

Religion in the colonies functioned not only as ideology but as cultural battleground. The soul became the final frontier of colonization, a space where resistance could be both silent and subversive.

Conclusion: The Colonial Legacy and the Silence of the Vanquished

The early colonization of Latin America was a project of monumental violence. It erased civilizations, enslaved millions, and reconfigured entire ecologies. Yet it also produced hybrid cultures, contested spaces, and enduring forms of resistance. The legacy of colonization cannot be confined to the ruins of temples or the archives of viceregal decrees. It lives in the rhythms of Latin American societies: in their languages, religions, inequalities, and revolutions.

To study this history is to confront the foundational contradictions of the modern world: that empire built its monuments on destruction, that progress coexisted with plunder, and that beneath every gold chalice was a ghost. The silence of the colonized is not absence but wound. It demands not pity, but reckoning.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Matthew Restall, Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 42–46.

- Camilla Townsend, Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 179–181.

- John Hemming, The Conquest of the Incas (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970), 91–96.

- Anthony Pagden, The Fall of Natural Man: The American Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 114–116.

- Bartolomé de las Casas, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, trans. Nigel Griffin (London: Penguin Books, 1999), 31.

- Charles Gibson, The Aztecs under Spanish Rule (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1964), 162–167.

- Lewis Hanke, The Spanish Struggle for Justice in the Conquest of America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1949), 83–86.

- Karen Spalding, Huarochirí: An Andean Society under Inca and Spanish Rule (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1984), 211–215.

- Robert Ricard, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966), 73–79.

- Barbara Ganson, The Guaraní under Spanish Rule in the Río de la Plata (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 142–148.

Bibliography

- de las Casas, Bartolomé. A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Translated by Nigel Griffin. London: Penguin Books, 1999.

- Ganson, Barbara. The Guaraní under Spanish Rule in the Río de la Plata. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003.

- Gibson, Charles. The Aztecs under Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1964.

- Hanke, Lewis. The Spanish Struggle for Justice in the Conquest of America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1949.

- Hemming, John. The Conquest of the Incas. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970.

- Pagden, Anthony. The Fall of Natural Man: The American Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Ricard, Robert. The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966.

- Spalding, Karen. Huarochirí: An Andean Society under Inca and Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1984.

- Townsend, Camilla. Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.07.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.