Grace Dalrymple Elliott by Thomas Gainsborough, 1778. © Metropolitan Museum of Art

By Joanne Major and Sarah Murden / 09.13.2016

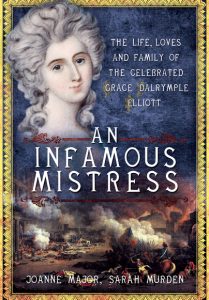

The infamous eighteenth-century courtesan Grace Dalrymple Elliott’s birth has not been recorded, but she was certainly born in Scotland, most likely in Edinburgh around 1754. She was to grow up to achieve a scandalous notoriety due to her divorce and high-profile lovers — but there was much more to Grace than mere scandal. She was a born survivor in a time when women had limited opportunities, she faced head-on the perils of the French Revolution, remaining in Paris, operating as a form of spy and courageously risking her life to save others. She later wrote down her recollections of those years, leaving behind one of the few first-hand accounts of the Reign of Terror written by a woman.

As a child the young Grissel Dalrymple (for that was her real name) lived in a very matriarchal household after her parents separated soon after her birth, but this ended when her mother died (in 1767) and she found herself placed in a French convent where she finished her education. Then, at around the age of sixteen, she left her convent for London, and her father Hugh Dalrymple’s home.

Adopting the Anglicised version of her forename, Grace, the young girl soon turned a few heads: she was a striking beauty and tall for the era.

Grace’s father Hugh Dalrymple was appointed Governor General of Grenada in the Caribbean. Perhaps this was the impetus for Grace’s hasty marriage in 1771; Hugh wished to see his daughter safely married before he left England. Grace’s choice of husband, given her youth and beauty, seems odd to us today but was perhaps not viewed in quite the same way at the time.

Her husband, Dr John Eliot, was a wealthy society doctor and a fellow Scot, but double Grace’s age and reputedly much shorter than his young bride too.

Grace’s indiscretions with the young and handsome Viscount Valentia led to a public Criminal Conversation case and divorce.

A son was born to the couple, who died young, and the marriage quickly fell apart. Although there were suggestions that Dr Eliot was entertaining a mistress, it was a man’s world and it was Grace’s indiscretions with the young and handsome Viscount Valentia in a London bagnio which led to a public Criminal Conversation case and divorce.

Before she was even legally an adult, Grace found herself a divorced and, in the eyes of the world, a ruined woman.

But Grace was a strong willed and resourceful woman, brought up in a household of similarly strong women. With few options open to her, she embarked upon a career as a courtesan.

For four years she enjoyed a relationship with the 4th Earl (later the 1st Marquess) of Cholmondeley, a tall, strapping and handsome peer of the realm with a dubious reputation but a steel core of honour running through him all the same. Grace hoped for marriage and to become her lover’s countess.

After Cholmondeley, Grace conquered Paris and the heart of the Anglophile Louis Philippe II, Duc d’Orléans before being enticed back to England at the young Prince of Wales’ request.

George IV when Prince of Wales, Royal Collection

‘Prinny’ (later George IV) had seen Grace’s portrait in Cholmondeley’s London townhouse and expressed a wish to meet the original. For a few short weeks Grace’s star was in the ascendancy amongst the London ton as she replaced the actress Mary Robinson (Perdita) in the prince’s affections.

When the prince’s interest began to wane, Grace found that she had managed to maintain a link to the royal purse; she was pregnant with the prince’s privately – if not publicly – acknowledged child.

Grace’s daughter was born on 30th March 1782, and she boldly named the prince as her child’s father on the baptism register. The young girl was given the feminine form of the prince’s names, Georgiana Augusta Frederica and, in later life, adopted Seymour as a surname. She was brought up by the Earl of Cholmondeley, Grace’s faithful old friend, as his ward.

With her daughter safely provided for, Grace returned to Paris and the arms of the Duc d’Orléans, little knowing that her next adventure was just around the corner.

Grace remained in Paris and its vicinity during the outbreak of the French Revolution and through the Reign of Terror.

Grace and King George IV’s daughter, Georgiana Augusta Frederica Elliott, later Miss Seymour (Met Museum)

There are strong suggestions that she operated as a form of spy, perhaps even as a go-between for her French lover and the Prince of Wales using letters sent to her daughter and Cholmondeley as a seemingly innocent means of communication. She certainly acted as a ‘middleman’, forwarding letters on to England from various sources, once facing questioning after her house had been searched and a sealed letter for the MP Charles James Fox found in her secretaire. The letter had come from Sir Godfrey Webster in Naples via an aide of the Duc d’Orléans and Grace had obviously been tasked with getting the letter out of France and in to England.

Grace also acted as a courier for the ill-fated French queen Marie Antoinette, taking a parcel to a pre-arranged destination as part of the preparations for the French royal family’s ultimately unsuccessful escape attempt, the ‘Flight to Varennes’. Grace was resourceful, courageous and intrepid, and she knowingly placed herself in danger.

This was demonstrated when she undertook to help the royalist fugitive Marquis de Champcenetz. When her plan to get him out of Paris was foiled, Grace smuggled Champcenetz back to her own house, bravely hiding him behind her bed when a patrol insisted on entering to search her rooms. Grace undoubtedly saved Champcenetz’s life, protecting him for several days before managing to get him to safety. It was doubly brave as she was marked as a royalist sympathiser due to her connection with the Duc d’Orléans, and Grace was questioned several times by the Comité de Surveillance and even held prisoner, whilst all the time the shadow of the guillotine loomed.

The title page of Grace’s journal

Despite the dangers, Grace survived those turbulent years. In later life and safely back in England, Grace put pen to paper and recorded her experiences during the revolutionary years. It is claimed that she did so at the behest of a doctor who was treating George III in his madness, and who wanted to read Grace’s manuscript aloud to the ailing king to entertain him. Tantalisingly, there may be some truth in that rumour.

This manuscript was never intended to be for public consumption but, many years after Grace’s death, her granddaughter published it (in 1859), as Grace’s Journal of My Life during the French Revolution.

Sadly, Grace’s granddaughter, with Victorian prudishness, may have edited it to present her beloved but infamous grandmother in a more respectable light and the editor, Richard Bentley, certainly embellished it to add in even more drama. Because of this, Grace’s Journal has often been discredited but the core of it is Grace’s own words and invaluable as one of only a few first-hand accounts of the revolution written by a woman.

The intrepid Mrs Elliott (she resolutely spelled her surname differently from her hated ex-husband) died in Ville d’Avray, Paris on the 15th May 1823. She had been ill for some time and had little left in the way of a fortune but she had been present at some of the most interesting events of her era, and was an intimate companion of many fascinating men and women.

Hers was a life well-lived and, moreover, one lived upon her own terms.