Investigating health and hygiene in 18th century Britain, against a backdrop of industrialization and the subsequent over-crowding in the cities.

By Dr. Matthew White

Visiting Research Fellow

University of Hertfordshire

Medical knowledge was very basic during the this period. While there were gradual improvements in healthcare, for many people even minor diseases could prove fatal.

Living Conditions

The growth of cities and towns during the 1700s placed enormous pressures on the availability of cheap housing. With many people coming to towns to find work, slum areas grew quickly. Living conditions in many towns consequently became unimaginable. Many families were forced to live in single rooms in ramshackle tenements or in damp cellars, with no sanitation or fresh air. Drinking water was often contaminated by raw sewage and garbage was left rotting in the street. Problems with the disposal of the dead often added to the stench and decay. Many London graveyards became full to capacity, and coffins were sometimes left partially uncovered in ‘poor holes’ close to local houses and businesses.

The death rate in most towns remained extremely high. In London, perhaps one in five children died before their second birthday. In certain districts the infant mortality rate reached 75% of all births whenever epidemics struck. During the 1700s more people died in London than were baptised every year. It was only the steady flow of migrants coming to the cities from rural areas, that prevented London’s population declining dramatically.

‘Mother Gin’

The rise of the ‘Gin Craze’ from the 1720s made matters worse. Distilling gin was inexpensive because of low corn prices: so much so that by 1750 nearly half of all British wheat harvests went directly into gin production. And the market for gin was huge. In London, the drink was incredibly popular with the poor. It was cheap and extremely strong, and for many people offered a quick release from the grinding misery of everyday life.

Already by the 1730s, over 6,000 houses in London were openly selling gin to the general public. The drink was available in street markets, grocers, chandlers, barbers and brothels. Of 2,000 houses in one notorious district, more than 600 were involved in the retail of gin or in its production. By the 1740s gin consumption in Britain had reached an average of over six gallons per person every year.

Many people believed that the drinking of gin was leading to a social crisis. Crime, poverty and a soaring death rate were all linked to the insatiable demand for ‘Madame Geneva’ as the drink was known. In 1751 novelist Henry Fielding argued that there would soon be ‘few of the common people left to drink it’ if the situation continued. The crisis required decisive political attention. In the 1740s and 50s Parliament was forced to pass a series of acts restricting both the sale of spirits and its manufacture, in order to bring the situation back under control.

Medicine

Due to the growing use of dissection as part of medical training, most doctors in the 1700s had a practical knowledge of the human body. Diagnosing and successfully treating disease, however, was often hit and miss. The connection between uncleanliness and the spread of diseases was not properly understood, and many people continued to die simply as a result of poor hygiene. Many women died in childbirth because of infection. Even having your teeth pulled out could be fatal. Major surgery was particularly dangerous. Dirty surgical instruments caused wounds to be infected, and this caused the death of many patients. Flea and rat infestations were also common, even in wealthy households, and many diseases were spread this way in crowded urban environments.

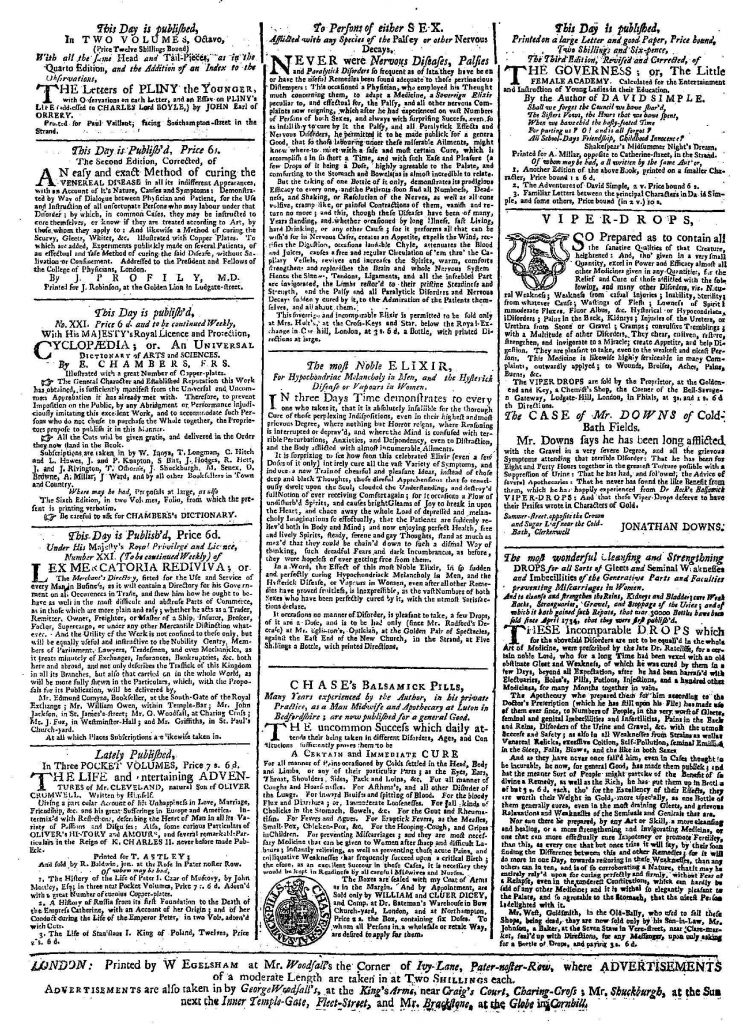

A doctor’s consultation was costly and often inconclusive. Most doctors dealt with only the wealthiest members of society, and the poor were often left to seek alternative forms of help. Lower down the scale, barber-surgeons might be called on to perform a range of surgical procedures: the removal of kidney stones, for example and the lancing of boils or setting of broken bones, or simply ‘letting the blood’ of patients for a whole range of ailments and conditions. Apothecaries might also be consulted, who were able to proscribe traditional drugs and remedies. In many towns charitable hospitals and dispensaries also offered basic healthcare: to poor children and expectant mothers, for example, or to old sailors and soldiers. And as a last resort, dozens of quacks were on hand to offer an array of (often useless) potions, powders and elixirs to those most desperate for relief from pain or discomfort.

Contagious diseases could be particularly devastating. Cholera, smallpox and typhus were all present in 18th century towns, and disease regularly carried off scores of people in only a matter of days. Smallpox was particularly frightening. The disease resulted in ugly skin eruptions across the body and face, and if not fatal, usually left patients horrifically scarred and sometimes blind.

Early in the century, however, experimentation began with new forms of smallpox inoculation. Early techniques involved injecting the disease into healthy patients, in order to build up their natural immunities. This highly dangerous method was refined later in the century, when Edward Jenner pioneered the use of cowpox as a less hazardous form of immunisation.

Originally published by the British Library, 10.14.2009, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.