The town crier, once indispensable to civic communication, has evolved from a functional necessity to a symbol of historical continuity.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The town crier, historically a vital conduit of information, occupied a central role in public communication for centuries. Before the advent of print and digital media, town criers—also known as bellmen—served as living newspapers, proclaiming laws, announcements, and news aloud in public spaces. The image of a loudly dressed figure ringing a bell and shouting “Oyez, Oyez!” remains embedded in the popular imagination, but behind this colorful symbol lies a deep and varied history. From ancient Greece and Rome through medieval Europe and into modern ceremonial functions, the town crier has adapted to changing media landscapes while maintaining a unique place in communal tradition. Here I explore the development of the town crier across historical epochs, examining their roles, functions, attire, and legacy in shaping the dissemination of public information.

Origins in Antiquity

Ancient Greece

The roots of the town crier trace back to ancient Greece, where heralds (kerykes) played a crucial role in civic life. These officials were responsible for relaying messages from city officials, delivering public proclamations, and even acting as envoys between states. Their authority was grounded in both tradition and sacred status; killing a herald was considered a serious crime, and they were often granted inviolability even in wartime (Hornblower, 1991).

Ancient Rome

In Rome, the role of the praeco (or public announcer) served a similar function. These individuals were employed to announce events such as gladiatorial games, political speeches, legal proceedings, and market days. Although not always formally integrated into the state apparatus, the praeco held a respected and visible place in public life. Roman criers also helped enforce timekeeping by signaling the opening and closing of markets and baths (Millar, 2002).

The Medieval Emergence of the Town Crier

Norman and Anglo-Saxon Influence

The medieval town crier as commonly imagined emerged in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. The convergence of Anglo-Saxon traditions of public proclamation with Norman legal and civic structures created a formalized role for criers. Royal proclamations, court orders, and local market regulations were read aloud in marketplaces and town squares (Owen, 1991).

The use of the word “crier” comes from the Old French crier, meaning “to cry out,” reflecting the role’s origin in both French and Anglo-Saxon cultures. Criers were appointed by local authorities, often under the jurisdiction of the mayor or lord of the manor, and their messages were legally binding. Illiteracy was common, so oral proclamation was essential to ensure information reached the populace.

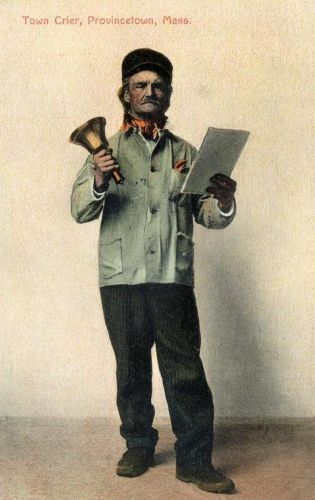

The Bell and the Cry

To capture attention, criers often rang a handbell or banged a wooden clapper. The word “Oyez” (pronounced “Oh yay”) derives from the Norman French for “hear ye,” signaling the crowd to listen to an official announcement. Town criers typically repeated each announcement three times to ensure clarity and comprehension.

Roles and Responsibilities

Legal and Civic Duties

Town criers were more than just messengers. They were law enforcers, witnesses, and civic officials. Their proclamations ranged from public notices and laws to lost property, executions, and events. Because they operated under civic authority, their announcements held legal standing—refusal to heed a crier’s proclamation could result in punishment.

Criers were also employed to issue summonses, and in many jurisdictions, their witnessing a notice was accepted in court as legal delivery. For example, in England, it was common for a town crier to summon defendants to court or publicly denounce criminals at large.

Guardians of Public Order

In smaller towns, criers sometimes took on additional roles such as town watchmen or even minor judicial duties. Their presence symbolized the authority of the crown or town council and contributed to the maintenance of public order.

Town Criers across Europe

England and Wales

In England, town criers reached their zenith in the 17th and 18th centuries. Almost every market town had one, and some larger cities had multiple criers for different wards. Criers were sometimes also used to read aloud the contents of newspapers to the public.

Scotland and Ireland

Scotland preserved a strong tradition of criers, known as “bellmen,” well into the 19th century. They announced births, deaths, auctions, and public events. In Ireland, town criers often operated in bilingual communities, making proclamations in both Irish and English.

France and the Continent

In France, crieurs publics were common during the Ancien Régime. Like their English counterparts, they read proclamations, court judgments, and other civic notices. French criers often used drums instead of bells and were key figures during the French Revolution for spreading news of political changes.

The Decline of the Town Crier

The Printing Press and Newspapers

With the rise of print media in the 16th and 17th centuries, the role of town criers began to diminish. Literacy rates improved gradually, and printed newspapers became the primary means of disseminating information. By the 19th century, the need for oral proclamation had greatly lessened.

Technological Advancements

The Industrial Revolution introduced new technologies—such as the telegraph and later the radio—that further rendered town criers obsolete. Municipal governments increasingly relied on printed bulletins, notice boards, and mailed correspondence.

Despite this, some towns retained criers as ceremonial figures or for specific purposes like auctioneering or festival announcements.

Town Criers in the Modern Era

Ceremonial and Touristic Roles

Today, town criers mostly serve ceremonial roles, appearing at festivals, parades, and historical reenactments. Some cities appoint official criers for heritage or tourism purposes. These modern criers wear traditional uniforms and may even participate in competitions for the loudest and most eloquent proclamation.

The Loyal Company of Town Criers, established in the UK, organizes such events and upholds standards for the role. Similarly, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand have maintained town criers as part of their colonial heritage traditions.

Legal Residue

Interestingly, some legal remnants of the town crier system still exist. In some British towns, proclamations must be made publicly by a town crier to satisfy legal requirements for local governance or royal announcements, such as the birth of a royal baby.

Cultural Representations and Legacy

In Literature and Art

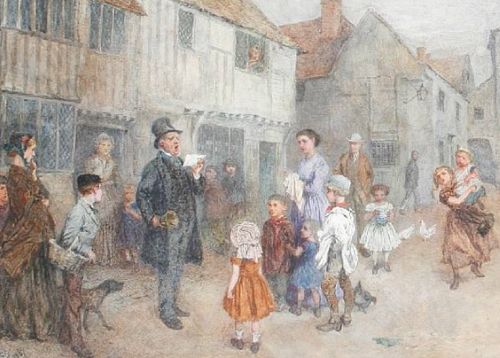

Town criers appear frequently in literature and drama, symbolizing both tradition and community. From Shakespeare to Dickens, they have served as plot devices and social commentators. In visual art, criers are often painted as quaint, colorful figures evoking nostalgia for pre-industrial society.

Folklore and Idioms

The expression “don’t shoot the messenger” can be traced back to ancient heralds and town criers who were protected by law. Similarly, the phrase “heard it on the grapevine” recalls older oral networks of communication in which criers were pivotal.

Case Studies

Chester, England

The city of Chester maintains one of the oldest traditions of town criers in the world. The Chester Town Crier delivers proclamations at a designated spot near the Cross, wearing a traditional livery and attracting tourists from across the globe.

St. John’s, Newfoundland

In Canada, the town crier of St. John’s, Newfoundland, is an important figure in civic life and a visible part of local tourism. The role was revived in the late 20th century as part of efforts to reconnect with maritime heritage.

Conclusion

The town crier, once indispensable to civic communication, has evolved from a functional necessity to a symbol of historical continuity. Their booming voices once echoed through the streets, carrying edicts, announcements, and the pulse of the community to citizens near and far. While modern communication technologies have rendered their primary function obsolete, the town crier remains a vibrant cultural icon, embodying the enduring need for shared public information and human connection.

Further Reading

- Hornblower, Simon. The Greek World, 479–323 BC. Routledge, 1983.

- Millar, Fergus. The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic. University of Michigan Press, 1998.

- Owen, Dorothy. The Records of the Established Church in England: Ecclesiastical Records. The British Records Association, 1991.

- Hadden, Sally E. Signposts: New Directions in Southern Legal History. University of Georgia Press, 2013.

- Loyal Company of Town Criers. Official Website. https://www.loyaltowncriers.com

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.15.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.