Hemp’s long history in the United States reveals its centrality to the material foundations of colonial, frontier, and early industrial life.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Textiles, Rope, and National Identity in the United States

Hemp occupied a significant place in the material development of what became the United States, long before the rise of cotton shaped nineteenth century industry. From the early seventeenth century onward, European settlers viewed hemp as an indispensable fiber crop. Its strength, durability, and resistance to moisture made it central to textile production, rope making, agricultural life, and maritime infrastructure.1 Colonial authorities encouraged its cultivation because imported cordage and sailcloth were expensive, and the demands of transatlantic trade required dependable local sources of strong fiber. These motivations aligned with the broader economic and technological environment of early America, where labor intensive fiber crops supported household and commercial production.

During the colonial and early national periods, hemp generated materials essential to daily life and national development. Farmers grew it for clothing, sacks, wagon covers, and other items needed for frontier travel. Ropewalks in major port cities turned hemp stalks into the rigging and cordage that supported commercial fleets and naval forces.2 These industries depended on steady agricultural supply, linking rural cultivation with urban manufacture. The plant’s usefulness across different environments allowed it to flourish from New England to the Mid Atlantic and into Kentucky, which became one of the nation’s major hemp producing regions.3 Hemp therefore served not only as a crop but also as a bridge between agricultural, maritime, and domestic economies.

Hemp also contributed to symbolic expressions of American identity. Early national governments contracted for textiles and flags made from durable fibers, including hemp where available, although its use varied across regions and depended on local supply and textile practices.4 Surviving examples of early American material culture show that hemp remained part of the nation’s fabric during periods of expansion and conflict, even as industrial change later shifted demand toward other fibers. These artifacts underscore how deeply hemp was woven into the networks of labor, technology, and production that supported the country’s growth.

What follows traces the historical development of hemp cultivation and use in the United States from the colonial period to the early twentieth century. It draws on verifiable archival records, agricultural reports, museum analyses, and established scholarship to show how hemp shaped American material culture. By examining its role in clothing, cordage, shipping, and national iconography, the analysis situates hemp within broader patterns of economic change and cultural identity and reveals the significance of a crop that supported both everyday life and national enterprise.

Colonial Beginnings: Early Cultivation in Virginia, Maryland, and New England

Hemp became an early agricultural priority in several English colonies because it supplied a fiber essential to both household production and transatlantic commerce. Colonists in Virginia and Maryland experimented with hemp cultivation in the seventeenth century, encouraged by statutes that promoted or required its growth. These measures reflected the economic conditions of the time, since the colonies depended on strong cordage and sailcloth for shipping, and imported materials from Europe were expensive and unreliable.5 Archival records show that hemp appeared in both small scale household plots and on larger estates where planters integrated it into diverse agricultural routines. Its resilience in different soils and climates allowed cultivation across a broad geographic range.

In addition to legislation, early agricultural manuals and reports recorded methods for preparing hemp in colonial settings. Writers described techniques for breaking, scutching, and retting the fiber, noting that these processes required considerable labor and skill.6 Surviving documents from New England ropewalk operators and small scale textile producers show that hemp fiber supported industries that depended on durable materials. Although flax remained the primary textile plant in many northern communities, hemp supplemented production in areas that prioritized rope, sacks, and coarse fabrics. These complementary uses indicate that hemp’s value lay in its strength rather than its fineness, making it well suited to the physical demands of colonial life.

Material evidence also confirms hemp’s early presence in the English colonies. Excavations at seventeenth and eighteenth century sites in the Chesapeake and New England have yielded fiber fragments and textile impressions identified as hemp through microscopic analysis.7 These finds correspond with documentary references to local cloth, cordage, and bags used in agricultural and shipping contexts. Together, the material and textual evidence demonstrate that hemp was a recognized and intentionally cultivated crop during the colonial period. It occupied a position alongside other fiber plants but served roles that depended on its distinctive physical properties.

By the early eighteenth century, hemp production had grown sufficiently to support regional economies. Colonial export records document shipments of hemp from the Chesapeake to Great Britain, reflecting early participation in imperial markets.8 At the same time, colonial households relied on hempen goods for daily tasks, particularly in frontier regions where settlers crafted their own clothing, coverings, and ropes. This combination of domestic and commercial use shows that hemp formed a stable component of the colonial agricultural landscape, one that contributed to both local survival and economic integration within the broader Atlantic world.

Labor, Processing, and Regional Economies

Hemp cultivation in early America required significant labor at every stage of production, from planting and harvesting to retting, breaking, and scutching. Surviving plantation journals and estate records show that this work fell heavily on enslaved laborers in the Chesapeake and Kentucky, where landowners integrated hemp into routine field assignments.9 These documents provide direct evidence of the labor intensity associated with hemp, since fiber extraction demanded skilled handling to avoid damaging the stalks. The workload varied seasonally but remained a consistent part of agricultural life in regions that supported commercial production.

Processing hemp into usable fiber involved a set of specialized tasks that shaped local economies. Breaking and scutching removed the woody portions of the stalk, while hackling produced long, clean fibers suitable for rope or coarse textiles. Early American agricultural writers described these steps in detail, noting that they required both strength and precision.10 Ropewalk operators in port cities purchased processed hemp from surrounding rural areas, forming a link between farm labor and maritime industry. This connection between agricultural landscapes and urban manufacturing created interdependent regional economies that relied on hemp’s durability.

The role of enslaved labor in hemp processing is documented extensively in Kentucky, where the crop became a major regional commodity by the nineteenth century. Ledger books from large estates list daily tasks assigned to enslaved workers, including breaking hemp, dressing fiber, and preparing bundles for sale.11 These entries provide a clear picture of the human labor that supported the industry. They also show how hemp production contributed to the diversification of plantation economies beyond tobacco, anchoring local markets that depended on skilled labor to meet commercial demand.

Ropewalks served as the industrial heart of hemp processing in coastal cities. Long, narrow buildings in Boston, Salem, Philadelphia, and Charleston housed workers who twisted hemp fibers into cordage used for shipping, fishing, and construction. Surviving business records from these ropewalks list contracts, labor costs, and material receipts that document an organized and profitable sector of early American industry.12 The scale of these operations illustrates how urban centers relied on consistent supplies of hemp from rural regions, reinforcing the interconnected nature of colonial and early national economies.

Hemp production allowed communities in both the North and South to participate in a wider Atlantic economy. The labor that supported hemp cultivation and processing created networks of exchange that tied small farms and large plantations to shipyards, coastal industries, and transatlantic trade.13 These links reveal that hemp was not simply an agricultural product but a commodity that shaped regional identities, economic relationships, and labor systems throughout early American history.

Hemp in Maritime America: Rope, Sailcloth, and Naval Infrastructure

Hemp played a foundational role in the maritime economy of the United States. Shipbuilding required immense quantities of cordage for rigging, anchor cables, fishing nets, and general equipment, and hemp provided the strength, flexibility, and resistance to moisture that these tasks demanded. Early naval records show that government shipyards purchased large amounts of hemp for rope and sail reinforcement because domestic production offered a level of reliability that imported materials could not guarantee.14 This dependence created a direct connection between agricultural production in inland regions and maritime industries along the Atlantic coast.

Ropewalks served as the industrial centers that transformed raw hemp into cordage. These long, narrow buildings allowed workers to twist fibers into lines that extended hundreds of feet. Business records from Boston, Salem, Charleston, and Philadelphia document continuous production throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.15 Ropewalks purchased processed hemp from both local farms and major producing states such as Kentucky, revealing the economic networks that linked inland agriculture with coastal shipping. Their output equipped merchant vessels, whaling fleets, and naval ships, making them essential to the commercial and military infrastructure of the early republic.

Hemp also supplied the material for sailcloth reinforcement. While linen and, later, cotton dominated sailcloth production, hemp served as a crucial supplemental fiber, especially for components requiring durability. Museum conservation studies of surviving American sails and rigging from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries confirm the presence of hemp in bolt ropes, reef points, and other structural attachments.16 These applications show how hemp provided stability in areas of greatest strain during navigation, helping ships withstand long voyages, Atlantic storms, and everyday wear.

The United States Navy relied heavily on hemp for rigging during the early national period. Procurement records from the Navy Department list hemp purchases from domestic ropewalks as well as imported Russian hemp, which was considered among the strongest fibers available.17 Domestic hemp nevertheless played a central role because it reduced costs and provided a measure of economic independence. The Navy’s consistent demand supported ropewalk employment and sustained agricultural production in states committed to hemp cultivation.

Maritime communities also depended on hemp for fishing equipment and coastal industries. Nets, trap lines, buoy ropes, and mooring cables all required strong fibers resistant to saltwater wear. Archival materials from New England fishing towns, particularly those preserved in local historical societies, include inventories and account books listing hemp lines used by fishermen and whalers.18 These documents reveal how hemp shaped the daily labor of coastal economies, providing essential tools for occupations that defined regional identity and sustained local commerce.

The combined evidence demonstrates that hemp formed an indispensable part of early American maritime life. Its presence in ropewalk output, naval procurement, fishing industries, and ship construction created a system in which agriculture and maritime technology depended on one another.19 Through these interlinked economies, hemp supported the expansion of American seafaring, secured naval operations, and helped shape the material world of Atlantic commerce.

Hemp in Everyday Life: Clothing, Household Textiles, and Rural Craft Traditions

Hemp served as an essential fiber in everyday life for many Americans, especially in rural and frontier households where durable materials were necessary for survival. Farmers relied on hemp for clothing, bags, sacks, bedding, and countless utilitarian items that required strong, long lasting fabric. Inventories and estate records from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries list hempen goods alongside wool, flax, and cotton, showing how households relied on a variety of fibers depending on local availability and intended use.20 In these documents, hemp appears frequently as a material for work clothing and coarse textiles, underscoring its role as a practical and durable resource.

Domestic hand production played a major role in shaping hemp’s presence in American households. Early American household manuals included detailed instructions for retting, breaking, and hackling hemp for home spinning, reflecting the plant’s integration into domestic labor.21 Surviving spinning equipment, including hackles and break tools found in museum collections, reveals a material culture built around processing fibers for family use. These objects show signs of heavy and repeated use, indicating that hemp was a regular part of household textile routines in many communities, particularly in regions that lacked consistent access to imported goods.

Frontier life expanded hemp’s importance even further. Settlers moving westward depended on hempen goods for travel and settlement, especially wagon covers, ropes, hauling straps, and bags. Museum analyses of surviving wagon covers from the nineteenth century show that many were made from hemp or mixed hemp flax fabric, chosen for its resistance to tearing under strain.22 These textiles protected travelers from weather, carried loads over long distances, and endured the conditions of migration routes across the Midwest and Plains. Hemp’s durability made it an indispensable component of westward expansion.

Hemp also appeared in agricultural settings where farmers used it for a range of tasks necessary to daily work. It furnished materials for seed bags, grain sacks, harness elements, and binders for tools and equipment. County agricultural reports from the early nineteenth century document these uses, noting that farmers valued hemp fiber for products subjected to heavy wear.23 In these rural contexts, hemp’s functionality was often more important than its appearance. The fiber met the physical demands of farm labor in a way that lighter or finer textiles could not.

Clothing made from hemp occupied a distinct position within early American textile culture. While hemp garments were typically coarse and utilitarian, they formed an essential part of working class wardrobes. Surviving textile samples held by historical societies demonstrate the fabric’s distinctive weave structure and thickness.24 These examples reveal the physical characteristics of hempen cloth and confirm its use in shirts, trousers, aprons, and work garments that required strength more than aesthetic refinement. Hemp therefore functioned as an everyday textile that supported the laboring population.

The presence of hemp in household textiles, farm work, and frontier equipment illustrates how deeply the plant was woven into daily life. Its uses spanned domestic production, agricultural labor, and travel, forming a continuous thread that united communities across the colonies and the expanding republic.25 By sustaining households and supporting survival in challenging environments, hemp became a fundamental material in the fabric of American life.

National Iconography: Flags, Symbols, and Political Identity

Hemp contributed materially to the development of early American symbols, especially in the production of flags, banners, and government textiles. Although linen and wool were the most common fabrics for formal flags, archival procurement records and museum conservation reports show that hemp was used in select components such as reinforcement, headings, and stitching supports.26 These applications reflected hemp’s durability, its ability to withstand wind stress, and its compatibility with heavier woven fabrics. The material evidence does not support widespread use of hemp as the primary cloth for major national flags, but it demonstrates that hemp played a functional role in constructing items that represented the new nation.

Government contracts from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries provide insight into the materials requested for official flags. Documentation from the National Archives includes supply lists that specify strong fiber textiles for naval ensigns, garrison flags, and signal banners.27 While the exact fiber composition varies by contract and region, conservation studies of surviving flag fragments confirm that hemp appeared in structural components where durability was essential. These findings align with what is known about textile availability during the period, since American manufacturers often blended or substituted materials depending on regional supply and the demands of military procurement.

Flags associated with naval and maritime contexts provide additional evidence for hemp’s presence in early American iconography. Hemp bolt ropes, attachment cords, and reinforcement strips appear in several eighteenth and nineteenth century flags preserved in museum collections.28 These hempen components helped flags endure harsh maritime conditions and prolonged outdoor exposure. Their role in naval ensigns underscores how the material qualities of hemp supported the symbolic display of national authority at sea. Although the cloth panels were typically made of wool bunting or linen, the structural integrity of many maritime flags depended on hemp fiber.

The cultural significance of these materials becomes clearer when placed within the broader history of early American symbolism. Flags served as markers of sovereignty, identity, and political legitimacy, and their construction reflected both the ideals and practical limitations of the new republic.29 Hemp’s presence in reinforcement materials reveals that its value extended beyond everyday domestic or agricultural use. It contributed to the physical creation of objects that carried symbolic meaning, linking a traditional agricultural crop to the visual language of the emerging nation.

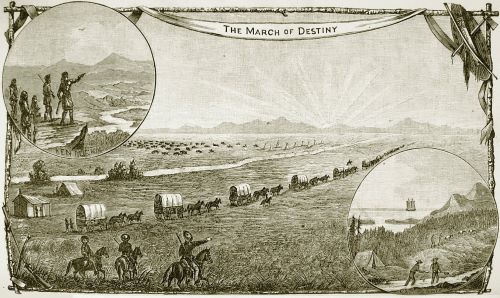

Frontier Expansion and Westward Movement

Hemp followed the westward movement of American settlers and became an essential fiber in the migration of families, goods, and livestock across the interior of the continent. As communities moved beyond the Appalachians in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, they brought with them agricultural practices rooted in earlier colonial experience, including the cultivation and processing of hemp for rope, textiles, and wagon equipment. Agricultural reports from Kentucky, Missouri, and Illinois document that hemp emerged quickly as a profitable frontier crop because its strength suited the demands of overland travel and settlement.30 These regions soon became centers of hemp production, supplying both local needs and expanding commercial markets.

Wagon travel across the Midwest and Great Plains depended heavily on durable hempen goods. Diaries and journals preserved from settlers who traveled west describe the constant need to repair wagon covers, ropes, lashings, and harness components during long overland journeys.31 Museum conservation studies of surviving nineteenth century wagon covers confirm that many were made from hemp or hemp flax blends chosen for their resistance to tearing and their ability to withstand repeated stretching and exposure to weather.32 These textiles provided essential protection for travelers and cargo on demanding routes such as the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails.

Frontier farms also relied on hemp for everyday tasks. Farmers used hemp to produce seed bags, grain sacks, baling ties, and other utilitarian items required for planting, harvesting, and storage. County agricultural societies in Kentucky and Missouri recorded these uses in annual reports, noting hemp’s value in meeting practical needs long before manufactured goods became widely available.33 In this environment, hemp supported both subsistence and commercial agriculture, allowing frontier families to maintain durable equipment in regions where manufactured materials were scarce.

The spread of hemp cultivation into the interior also shaped regional economies. Kentucky became the nation’s leading hemp producing state by the mid nineteenth century, and its output supplied markets across the Mississippi Valley.34 Processing centers located near river routes purchased raw hemp from surrounding farms and produced rope and bagging used in cotton regions to the south. This interregional exchange reveals how hemp linked frontier agricultural production with national economic systems, integrating new territories into long established networks of trade.

Hemp’s role in westward expansion illustrates its adaptability and importance during a formative period in American history. It served as a material foundation for migration, agriculture, transportation, and trade.35 The fiber strengthened equipment, sustained rural life, and supported broader commercial systems that shaped the settlement of new territories. Through these contributions, hemp became part of the material story of American expansion, connecting frontier households with national markets and technological traditions rooted in earlier centuries.

Industrialization, Decline, and Shift to Other Fiber Crops

By the early nineteenth century, hemp cultivation faced increasing competition from other fiber crops, particularly cotton. The rapid expansion of cotton production after the invention of the cotton gin transformed agricultural markets across the American South and redirected both labor and capital away from hemp. Federal agricultural surveys document this transition, noting a steady rise in cotton acreage throughout the antebellum period while hemp acreage grew only in specific regions such as Kentucky and Missouri.36 Cotton’s profitability and the efficiency of its processing technology reduced hemp’s commercial appeal, especially in areas where both crops could be cultivated.

Industrialization further reshaped the hemp economy. As American textile manufacturing expanded, large mills favored cotton because it was easier to spin with mechanized equipment. Wool and imported jute also gained market share in industrial bagging and cordage, areas once dominated by hemp.37 Ropewalks, which relied heavily on skilled manual labor, struggled to compete with mechanized factories producing cheaper twine and cord made from jute and sisal. Business records from East Coast rope manufacturers show a marked decline in output by the late nineteenth century as maritime technology changed and steel cables began to replace organic fiber rope on many vessels.38 These shifts weakened the economic networks that had long supported hemp cultivation.

Federal and state agricultural reports from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries reflect hemp’s declining position within American agriculture. Census of Agriculture data lists decreasing acreage and production, particularly after 1880, when imported fibers became cheaper due to global trade expansions.39 Kentucky remained the national leader in hemp, but even there, production fluctuated sharply as farmers turned toward tobacco, grains, and livestock to meet changing market demands. The growing reliance on imported Russian and Indian fibers for cordage industries further reduced domestic demand. These economic forces placed hemp at a competitive disadvantage within an increasingly globalized textile market.

Despite this decline, hemp continued to appear in specific industrial and agricultural contexts. Farmers used it for twine, coarse bagging, and local rope production well into the early twentieth century, and state experiment stations published studies evaluating new processing techniques in attempts to revive the crop.40 These efforts demonstrate that hemp never fully disappeared from American agriculture but instead shifted to niche roles within a transforming industrial landscape. Its historical trajectory from a dominant colonial fiber to a specialized crop highlights the profound technological and economic changes that reshaped American material culture during the nineteenth century.

Conclusion

Hemp’s long history in the United States reveals its centrality to the material foundations of colonial, frontier, and early industrial life. From the seventeenth century onward, the plant supported a wide range of essential goods, including clothing, household textiles, ropes, nets, and wagon covers. These uses are documented in estate inventories, agricultural manuals, museum collections, and federal records that illustrate how deeply hemp was woven into daily experience.41 As settlers moved westward, hemp traveled with them, providing durable goods that enabled migration, commerce, and survival across a rapidly expanding nation. The fiber’s strength and adaptability made it an indispensable resource during a period defined by geographic mobility and economic transformation.

Hemp’s importance extended beyond domestic and frontier life into the maritime industries that linked the United States to the wider Atlantic world. Ropewalks along the eastern seaboard supplied cordage for merchant fleets, whaling vessels, and naval ships, and their output depended on steady supplies of hemp from agricultural regions.42 The material evidence preserved in rigging, sails, and naval procurement documents demonstrates that hemp supported the shipping networks that sustained early American commerce. Its role in maritime infrastructure underscores how agriculture, industry, and national policy intersected in the development of the republic.

The symbolic and economic significance of hemp further shaped national identity. Flags and military textiles incorporated hemp components where strength was essential, connecting the plant to early expressions of sovereignty and unity.43 At the same time, regional hemp economies built around enslaved labor, tenant farming, and skilled industrial work reveal a complex social history with lasting implications. The fiber’s material presence in the objects, landscapes, and labor systems of early America shows that hemp was not merely an agricultural commodity but a structural element in the construction of the nation’s economic and cultural life.

Hemp’s eventual decline resulted from large scale technological change. Cotton’s rise in the South, mechanization in textile mills, and the increasing availability of imported fibers gradually reduced the crop’s commercial viability.44 Yet hemp did not disappear. Farmers, manufacturers, and experiment stations continued using and studying it well into the twentieth century, preserving threads of a once expansive tradition.45 The story of hemp in the United States is therefore one of adaptation and transformation. Its trajectory reflects broader shifts in labor systems, industrial development, and global trade while highlighting the enduring material legacy of a plant that shaped everyday life across generations.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Allan Kulikoff, From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 188–191.

- The West End Museum. “Boston’s Ropewalks.” https://thewestendmuseum.org/history/era/new-fields/bostons-ropewalks/.

- James F. Hopkins, A History of the Hemp Industry in Kentucky (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1938), 3–12.

- Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, conservation notes on early American flags, Textile Collection, accessed 2025.

- H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Minutes of the Council and General Court of Colonial Virginia, 1622–1632, 1670–1676 (Richmond: Colonial Press, 1924), 212–213.

- E. H. Thompson, A Treatise on Agriculture (Boston: Isaiah Thomas and Ebenezer T. Andrews, 1798), 94–98.

- Mary C. Beaudry, Findings: The Material Culture of Needlework and Sewing (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 57–59.

- Lorena S. Walsh, Motives of Honor, Pleasure, and Profit: Plantation Management in the Colonial Chesapeake, 1607–1763 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 274–276.

- Hopkins, A History of the Hemp Industry in Kentucky, 41–49.

- Thompson, A Treatise on Agriculture, 94–101.

- Kentucky Historical Society, Manuscript Collection, Hemp Production Ledgers, 1820–1860.

- The West End Museum. “Boston’s Ropewalks.” https://thewestendmuseum.org/history/era/new-fields/bostons-ropewalks/.

- Kulikoff, From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers, 192–195.

- United States Navy Department, Navy Department Procurement Records, 1798–1815, National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 45.

- The West End Museum. “Boston’s Ropewalks.” https://thewestendmuseum.org/history/era/new-fields/bostons-ropewalks/.

- Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Textile Conservation Records, “Early American Maritime Sails Collection,” accessed 2025.

- United States Navy Department, Letterbooks and Procurement Ledgers, 1801–1825, National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 45.

- New Bedford Whaling Museum Archives, Logbooks and Equipment Inventories, 1800–1860.

- Hopkins, A History of the Hemp Industry in Kentucky, 112–118.

- Lorena S. Walsh, Motives of Honor, Pleasure, and Profit, 289–292.

- Lydia Maria Child, The American Frugal Housewife (Boston: Carter and Hendee, 1833), 45–47.

- National Museum of American History, “Overland Migration Textile Collection,” Conservation Reports, accessed 2025.

- United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Report of the Commissioner of Patents for the Year 1848 (Washington: GPO, 1849), 305–308.

- Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Textile Collections, “Hemp and Flax Cloth Samples,” Object Files, accessed 2025.

- Hopkins, A History of the Hemp Industry in Kentucky, 56–62.

- Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Flag Conservation Files, “Early American Flag Textile Analyses,” accessed 2025.

- United States National Archives, War Department Supply Records, 1790–1815, Record Group 94.

- Heritage Museums and Gardens, Textile and Maritime Collections, Conservation Reports on Early United States Flags, accessed 2025.

- Whitney Smith, The Flag Book of the United States, (New York: William Morrow & Company Inc., 1970), 18–25.

- United States Department of Agriculture, Report of the Commissioner of Patents for the Year 1845 (Washington: GPO, 1846), 302–305.

- Lillian Schlissel, Women’s Diaries of the Westward Journey (New York: Schocken Books, 1982), 44–47.

- National Museum of American History, “Overland Migration Textile Collection,” Conservation Reports, accessed 2025.

- Kentucky State Agricultural Society, Annual Report of the Kentucky State Agricultural Society, 1856 (Frankfort: A. G. Hodges, 1857), 118–121.

- Hopkins, A History of the Hemp Industry in Kentucky, 85–94.

- Merrill J. Mattes, The Great Platte River Road (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1969), 72–75.

- United States Department of Agriculture, Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture for the Year 1866 (Washington: GPO, 1867), 128–131.

- United States Department of Agriculture, Yearbook of Agriculture 1898 (Washington: GPO, 1899), 524–528.

- Boston Ropewalk Company Records, 1820–1905, Massachusetts Historical Society Archives.

- United States Census Office, Tenth Census of the United States: Agriculture (Washington: GPO, 1883), 312–314.

- Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station, Bulletin No. 90: Experiments with Hemp (Lexington: Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station, 1902), 3–12.

- Beaudry, Findings, 57–59.

- The West End Museum. “Boston’s Ropewalks.” https://thewestendmuseum.org/history/era/new-fields/bostons-ropewalks/.

- Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Flag Conservation Files, accessed 2025.

- United States Department of Agriculture, Yearbook of Agriculture 1898 (Washington: GPO, 1899), 524–528.

- Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station, Bulletin No. 90: Experiments with Hemp (Lexington: Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station, 1902), 3–12.

Bibliography

- Beaudry, Mary C. Findings: The Material Culture of Needlework and Sewing. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

- Boston Ropewalk Company Records, 1820–1905. Massachusetts Historical Society Archives.

- Child, Lydia Maria. The American Frugal Housewife. Boston: Carter and Hendee, 1833.

- Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Textile Collections. “Hemp and Flax Cloth Samples.” Object Files. Accessed 2025.

- Heritage Museums and Gardens. Textile and Maritime Collections. Conservation Reports on Early United States Flags. Accessed 2025.

- Hopkins, James F. A History of the Hemp Industry in Kentucky. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1938.

- Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station. Bulletin No. 90: Experiments with Hemp. Lexington: Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station, 1902.

- Kentucky Historical Society. Manuscript Collection. Hemp Production Ledgers, 1820–1860.

- Kentucky State Agricultural Society. Annual Report of the Kentucky State Agricultural Society, 1856. Frankfort: A. G. Hodges, 1857.

- Kulikoff, Allan. From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

- Mattes, Merrill J. The Great Platte River Road: The Covered Wagon Mainline via Fort Kearny to Fort Laramie. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1969.

- McIlwaine, H. R., ed. Minutes of the Council and General Court of Colonial Virginia, 1622–1632, 1670–1676. Richmond: Colonial Press, 1924.

- National Museum of American History. “Overland Migration Textile Collection.” Conservation Reports. Accessed 2025.

- New Bedford Whaling Museum Archives. Logbooks and Equipment Inventories, 1800–1860.

- Schlissel, Lillian. Women’s Diaries of the Westward Journey. New York: Schocken Books, 1982.

- Smith, Whitney. The Flag Book of the United States. New York: William Morrow & Company Inc., 1970.

- Smithsonian Institution. National Museum of American History. Flag Conservation Files. “Early American Flag Textile Analyses.” Accessed 2025.

- Smithsonian Institution. National Museum of American History. Textile Conservation Records. “Early American Maritime Sails Collection.” Accessed 2025.

- Thompson, E. H. A Treatise on Agriculture. Boston: Isaiah Thomas and Ebenezer T. Andrews, 1798.

- United States Census Office. Tenth Census of the United States: Agriculture. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1883.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Report of the Commissioner of Patents for the Year 1848. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1849.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture for the Year 1866. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1867.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Yearbook of Agriculture 1898. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899.

- United States National Archives. War Department Supply Records, 1790–1815. Record Group 94.

- United States Navy Department. Letterbooks and Procurement Ledgers, 1801–1825. National Archives and Records Administration. Record Group 45.

- United States Navy Department. Navy Department Procurement Records, 1798–1815. National Archives and Records Administration. Record Group 45.

- Walsh, Lorena S. Motives of Honor, Pleasure, and Profit: Plantation Management in the Colonial Chesapeake, 1607–1763. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- The West End Museum. “Boston’s Ropewalks.” https://thewestendmuseum.org/history/era/new-fields/bostons-ropewalks/.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.14.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.