Heraldry was extremely useful for the communication of claims to territory.

By Dr. Mario Damen

Senior Lecturer in Medieval History

University of Amsterdam

By Dr. Marcus Meer

Historian of Urban Communication and Visual Culture

German Historical Institute of London

Introduction

In this essay1 we analyse coats of arms as a powerful and versatile tool of late medieval communication. We explore how territorial titles and claims of kings, princes, nobles, and urban elites alike were translated into heraldic signs and communicated to socially diverse audiences. The ubiquity of territorial heraldry is demonstrated in manuscript sources, including armorials, chronicles, illuminations and account books, as well as for visual and material sources such as heraldically decorated objects such as banners, painted walls, and stained glass in town halls, churches, and noble palaces. We examine the interplay of heraldry and territory in its textual, visual, material, and performative dimensions in order to show how heraldic communication was used to represent and (re)construct complex territorial structures in the Late Middle Ages.

In January 1470, Jehan Hennequart, painter and valet to Charles the Bold, duke of Burgundy (r. 1467-1477), carved two figures destined for the chapel of the ducal residence in The Hague. The first figure represented Charles’s father, the late Philip the Good (r. 1419-1467), and the second represented the late Willem VI, count of Holland (r. 1404-1417). Both men were shown ‘ready to fight on the battlefield’: Philip was armed with a battle axe and a dagger while Willem carried a lance (Fig. 9.1). They must have been easily recognisable to late medieval observers, since each held a shield painted with his coat of arms. But the painter also added several other heraldic signs which conveyed yet more information: next to Philip the Good, Hennequart painted a small panel quartering the coats of arms of the duke’s grandparents, juxtaposed with a larger panel comprising the seventeen coats of arms of Philip the Good’s duchies, counties, and lordships.2 This latter arrangement was, notably, not an exact heraldic survey of all Burgundian lands and lordships. Rather, it was a visual shorthand, summarising the extensive patchwork of principalities under ducal rule, not all of which resulted from ‘natural’ inheritance.3

Like so many late medieval kings and princes, the dukes of Burgundy were keen to keep alive the memory of their forebears. They constantly commissioned tombs, stained glass, and statues or figurines of their predecessors in chapels and churches in towns like Lille, Ghent, Brussels, Mons, and The Hague. They also created a monumental burial place dedicated to their dynasty at the Carthusian monastery of Champmol near Dijon.4 It was crucial for the dukes to underline their genealogical connection to their predecessors in this way, since so many claims of legitimacy in the Middle Ages rested on the natural line of succession by means of which the dynasty had acquired its possessions.5 However, in the case of the burial chapel in The Hague, the heraldically portrayed succession was not at all ‘natural’. The four heraldic quarters of Philip the Good, representing his four grandparents, indicated a clear line to the house of Bavaria, the former rulers of the county of Holland. Philip’s mother was Margaret of Bavaria, daughter of Duke Albert (r. 1358-1404) and sister of Count Willem VI. But despite this apparently unambiguous genealogical descent, the incorporation of the county of Holland and that of Zeeland into the Burgundian composite state in 1433 was the result of political manipulation, intrigues, and warfare. None of these struggles are remembered in the princely chapel. Here, Philip the Good used coats of arms to connect his dynasty firmly and unequivocally to the principalities it had gained in the past.

As this example would suggest, and as we will argue in the remainder of this essay, heraldry was extremely useful for the communication of princely claims to territory. Of course, a princely chapel was a highly exclusive space with restricted access, so the audience of this specific heraldic configuration was likely rather limited socially. But how did heraldry relate to the construction and representation of territory in the Middle Ages more generally? To answer this question, it is essential to understand ‘territory’ not as a given, but as the outcome of a rather complex process. Stuart Elden characterises territory as the political notion of space, a ‘political technology’ even. In Elden’s view, territory is more than simply a bounded or enclosed area: it includes both the politico-economic connotation (land) and the politico-strategic con-notation (terrain), but at the same time it involves the management of space through a variety of policies and techniques. To analyse the notion of territory in any historical setting, it is therefore important to look at territorial practices – ‘practices that relate politics or power to place’ – and representations of territory in concert.6 In this essay, we will argue that heraldry was an important part of such practices in late medieval Europe. Territorial titles and claims of kings, princes, nobles, and urban elites alike were translated into and communicated by means of heraldry in a wide range of media (e.g. seals, manuscripts, tombs, gates, etc.). Over time, the signs themselves obtained territorial connotations and began to represent territories or claims to space, just as their material expressions were consciously placed in spaces to reflect or establish claims to authority over territories. In short, just as coats of arms were represented in space, they came to represent space, adding meaning(s) to both the direct physical environment in which they were placed and the larger territorial space they symbolised.7

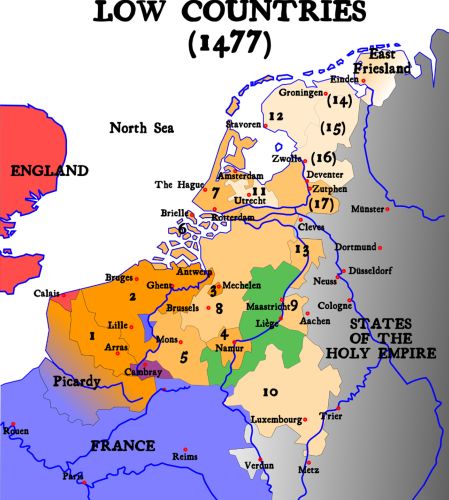

This essay focuses primarily, but not exclusively, on cities and principalities situated in the Burgundian Low Countries and the Holy Roman Empire. In these politically fragmented areas, urban influence was relatively strong, with princely and imperial authority being contested continuously.8 We will study the interplay of heraldry and territory in various media to analyse how coats of arms were used to represent and (re)construct authority in complex territorial structures. Starting with the heraldic signs themselves, this essay will show that coats of arms acquired noticeably territorial associations over the course of the Middle Ages. These associations were represented and reinforced in manuscripts, for example: armorials compiled and structured coats of arms in relation to space, whilst narrative sources such as chronicles, too, related coats of arms to territorial entities. The same territorial dimension of heraldry found its expression in material culture. Painted walls, carved stones, and stained glass in noble palaces, churches, and town halls, for instance, show how extensive arrangements of heraldic signs evoked notions of territory, demarcating dedicated spaces or representing diverse territorial structures. Such displays were not necessarily permanent in nature, but were also created specifically for temporary occasions such as Joyous Entries. This ephemeral side to the relation of heraldry in territory is best seen in conflicts prompted by heraldic displays meant to establish claims to authority. Thus, this essay also highlights the performative character of heraldic communication, suggesting that awareness of such signs and their territorial implications existed throughout all layers of late medieval societ y.

What’s in a Shield? Coats of Arms and Territories

There is no lack of interest in the territorial dimensions of coats of arms on the part of established heraldists.9 On the one hand, this interest can be linked to astonishing modern continuities: many coats of arms still in use today are territorial in nature, identifying districts, regions, and even states on official flags and government documents, or embellishing local products and tourist merchandise. On the other hand, this interest is the result of a contradiction that requires explanation: the territorial perception of heraldry seems to defy the oft-repeated opinion that coats of arms ‘proper’ emerged in the twelfth century as, f irst and foremost, steady and soon hereditary personal identifiers of fighting noblemen, before they were also adopted by non-noble persons such as townsmen and even peasants, just as corporate bodies (e.g. monasteries, cities, guilds) began to create heraldic signs for themselves.10 However, as scholarship on the place of heraldry in medieval society stresses, any coat of arms was a highly polyvalent sign, far from restricted to a unidimensional role as the visible marker of a person and their dynasty or an institution and its continuity.11

As heraldic scholar Paul Adam-Even suggested, there were territorial dimensions to coats of arms as well, potentially even before they became the shared visual inheritance of medieval dynasties. According to Adam-Even, initially twelfth- and thirteenth-century lords had their bannerets and vassals, who were tied to their land, display their lordly heraldry, often on banners, on the battlefield, so that these symbols became firmly associated with the fiefs that provided – literally – the ground for these feudal bonds. As a result, arms gradually became associated with the land and eventually remained unchanged even when the lord in control of a fief changed. The new lord often adopted the arms of his f ief and its land, combining them with his inherited arms or abandoning his accustomed arms altogether in favour of the territorial arms.12

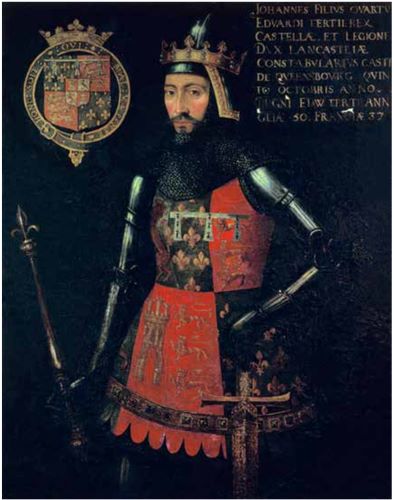

The most frequent simultaneous transmission of arms and territories appeared in the context of inheritance. Many lords chose to visualise the inheritance of another significant possession by adopting the arms associated with the new land’s former lord. This approach resulted in often complex combinations of multiple coats of arms in a single shield, since the new owners were usually keen to show the full extent of their possessions by means of heraldry.13 This ‘marshalling’ of two or more coats of arms resulted in the famous arms of the Kingdom of Castile and Leon, for example. When Ferdinand III (r. 1217-1252) inherited the two formerly independent kingdoms in 1230, he united them both politically and heraldically.14 The royal arms of Castile and Leon also illustrate the importance of women for heraldic and territorial inheritance: once John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster (r. 1362-1399), married his second wife, Constance, daughter of King Peter I of Castile and Leon (r. 1350-1369), in 1371, he felt entitled to claim the king-dom of Castile and Leon, combining his own arms with the royal arms of Castile and Leon by adding an inescutcheon of pretence to his coat of arms (Fig. 9.2).15 As this example shows, heraldry was a shared phenomenon of late medieval culture which enabled kings and princes across Europe to combine representations of their territories even when separated by long distances. Heiresses played a key role in this process, since they passed on their entire patrimony – lands, titles, and arms – to their husbands, who often chose to show this appropriation by combining their wives’ heraldry with their own.16

If a land-holding lineage died out, their fiefs reverted to the ruler, who was authorised to grant these to a new vassal (or new vassals). Repeatedly, this acquisition of land by investiture was accompanied by the acquisition of the coat of arms of the now extinct family.17 In this context of investiture, banners and the coats of arms they displayed were highly significant. In the Holy Roman Empire, banners provided the symbolic means of princely investiture, indicating the prince’s ability to summon his vassals for war.18 Although their iconography usually predated the advent of heraldry and was thus not necessarily heraldic in appearance, throughout the Late Middle Ages the arms of noble dynasties became more frequently displayed on banners and thus associated with the transferred territory.19 Of course, banners also served as a ‘visual focus for troops’ morale and cohesion’ in battle.20 Precisely because banners were thus at the heart of warfare as the raison d’être of feudal relations, they and the arms they showed must have come to be seen as more abstract symbols for such ties as well.

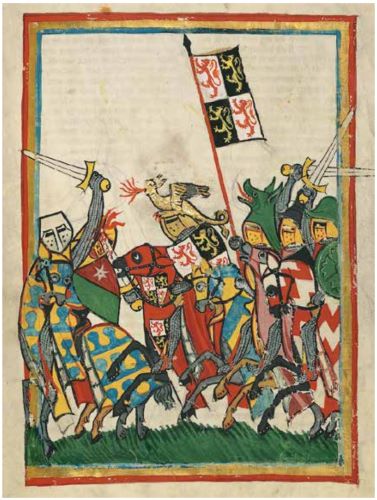

Warfare itself was a common way of acquiring land and its associated arms in medieval Europe. In 1288, Jan I, duke of Brabant (r. 1267-1294), conquered the Duchy of Limbourg after the Battle of Woeringen. On a well-known miniature from the Manesse codex (c. 1300-1340, see Fig. 9.3), he is depicted carrying a banner with the quartered arms of Brabant and Limbourg. Interestingly, it was only his son Jan II who would bear this quartered coat of arms with the heraldic lions of Brabant and Limbourg from 1298 onwards, as seals of Jan I and Jan II show. However, more than a century later, in 1415, the chronicler Henne van Merchtenen wrote that Jan I, ‘who won the rich land of Limbourg […] in the manner of a brave prince’, personally quartered his coat of arms after he ‘destroyed the castle of Woeringen’. This ‘predating’ of the unity of Brabant and Limbourg, implied by their heraldic unification, served as a seemingly historically grounded claim to the duchy, presented to both the wider public and princely competitors as an argument against any challenge to the allegedly long-established rights of the duke.21

The ruler’s subjects, particularly those in towns, were sometimes themselves keen to ensure an appropriate heraldic representation of ‘their’ territory in their ruler’s coat of arms, as in the case of the Burgundian composite state. On the succession of Philip the Good to the ducal throne of Brabant in 1430, the Estates of the duchy made the prince promise to ‘adopt the titles and arms of Lotharingia, Brabant, Limbourg, and of margrave of the Holy Roman Empire, as was appropriate’.22 Subsequently, Philip quartered his arms of Burgundy with the golden lion on a black field (Brabant), and the red lion on a silver f ield (Limbourg). However, although Philip the Good acquired more principalities in the 1430s, Holland and Zeeland for example, he did not change his coat of arms again. The same applies to Charles the Bold, who maintained his father’s arms even after he had acquired another two duchies. Perhaps the dukes did not want to divide their personal coat of arms into smaller parts for reasons of visibility and recognizability.23

The most mundane procedure to express the link between heraldry and territory was the purchase of land and the use of the associated arms. Thus, the Leuchtenberg landgraves Louis (r. 1463-1487) and Frederick (r. 1463-1486) sold the county of Hals in 1486 alongside the coat of arms that had once belonged to the long extinct counts of Hals.24 Just how matter of course this practice must have been is further demonstrated by legal provisions that created explicit exceptions: when Duke Albert of Mecklenburg (r. 1348-1379) had purchased the county of Schwerin from Count Nicholas of Schwerin and Tecklenburg, the charter emphasised that the count and his son preserved their right ‘to use the arms of the county of Schwerin as before’.25

Territories in Armorials and Chronicles

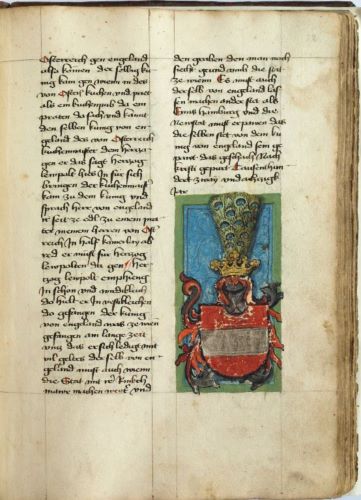

One place in which such connections between coats of arms and territories were created, preserved and reinforced, visually and textually, are manuscripts. A prime example for the heraldic wealth of these sources is the late-fourteenth-century Chronicle of the Ninety-Five Austrian Lordships. Written for the house of Habsburg, the chronicler combined a history of Austria with extensive heraldic displays when setting out the succession of legendary predecessors of the land’s former rulers, all the way back to Abraham. In this effort, the text also implies an association of heraldry with Austria’s territory. Initially, the chronicle describes and depicts ‘how often the land’s arms have changed’ as new houses established their rule. Eventually, however, the various arms of Austrian rulers of old were replaced with the arms of the house of Habsburg, whose shield, the chronicler’s efforts seem to suggest, was to become the ultimate sign of the Austrian lands.26

The Habsburg arms later found their way into a conspicuous heraldic arrangement in the so-called Haggenberg armorial (c. 1488), which pays homage to Emperor Frederick III (r. 1440-1493) with a splendorous heraldic illumination (Fig. 9.4). Unlike other depictions of the imperial arms accompanied by the Reichsquaternionen27 – a heraldic representation of the Holy Roman Empire’s structure – the illumination in the Haggenberg armorial focuses on the various possessions of the house of Habsburg, represented by their arms grouped in a circle around Frederick and the imperial arms.28 These circular heraldic representations later received a larger audience when they were incorporated in panels featuring Charles V (r. 1506-1555), made for the town hall of Mechelen in 1517-1518 by Jan van Battel, and again after his coronation as emperor in 1519. In these configurations the coats of arms surrounding the f igure of Charles represented his Spanish territories, which he had formally acquired upon his coronation after the death of his grandfather Ferdinand II of Aragon (r. 1479-1516).29

Medieval armorials were a frequent place for the visual demonstration of such possessions. As most recently Elmar Hofman’s doctoral thesis shows, these manuscripts were far from simple collections of coats of arms, but instead carefully curated to serve very different purposes, one of which was to ‘map’ the territories of a region or indeed the world at large, compiling both real and attributed coats of arms with territorial associations.30 The structure of armorials is often based on the so-called marches d’armes, territorial units going back to the times of Charlemagne, according to a tournament treatise by the French writer Antoine de La Sale (c. 1385-c. 1460). La Sale states that this ruler was the founder of the two original marches d’armes, ‘who in arms and tournaments are called’ Ruyers and Poyers, separated by the river Rhine. Later, other emperors and kings, La Sale claimed, created new marches within and outside their territories. For the Empire, he specifically mentioned the alienation of several basses marches on the other side of the Rhine, ‘which would be called at tournaments Brabanters, Hainauters, Liegois, Ardenois, Hesbaeyois […] rather than Poyers’. The French king supposedly also divided the Poyers into three marches: Poyers, Aquitains, and the Champagnois, with several provinces et pays each. Further fragmentation occurred when brothers and children of the king were given duchies and counties, which eventually lead to the creation of another nine marches.31

The question whether the term marche d’armes was at all territorial in semantic scope is difficult to answer: even specialists like Michel Pastoureau and Michel Popoff admit that the term is difficult to define. They are of the opinion that a marche d’armes is at the same time a geographical entity (a specific region such as a county, a duchy, or a kingdom) and a feudal entity (a group of fiefs) without any clear boundaries but rather dependent on a variety of rights, homages, and pretensions.32 Of course, there is an important disclaimer to be added: the compilers of these armorials were not primarily interested in an exact historical reconstruction of specif ic marches d’armes. Instead, they created these ‘collections’ to offer their patron and the courtly audience an overview of the coats of arms used in that marche during a certain period. What is more, they seldom used the word marche in their manuscripts.

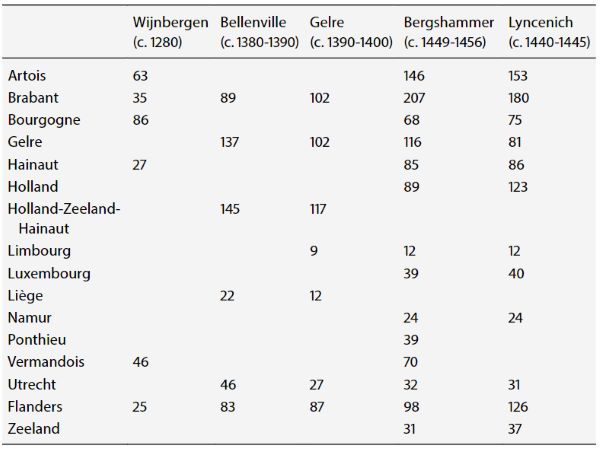

Hofman argues that most armorials are characterised by a straightforward representation of principalities rather than a strictly applied survey of marches d’armes in their heraldic sense.33 However, our analysis of five armorials compiled between 1280 and 1450 shows that the heraldic representation of the marches d’armes located in the Low Countries underwent changes in their territorial ‘framing’ (Table 9.1). The politically and economically important principalities of Brabant and Flanders, for example, are integrated in all five armorials, followed by Guelders and Holland. The latter are sometimes combined with Hainaut and/or Zeeland, thus reflecting the personal union of these principalities. In the fifteenth century, Flanders and Brabant became the heart of the Burgundian composite state, and this emerging union is clearly visible in the earlier armorials. That being said, the marches as represented in these armorials are clearly based on personal ties and not on ‘land’. The possession of lordships seems to have been the guiding principle of the composition of the marches. The sum of the coats of arms represented the principality as a territory that was constructed on the basis of noble lordships. It was partly a heraldic embodiment of noble space and partly a reflection of the actual possessors of the lordships.

A closer look at the first coat of arms of all these marches, each representing the person supposed to be its leader, shows an interesting change. In the Wijnbergen armorial from c. 1280, the coats of arms of the counts and dukes are not portrayed as larger than those of bannerets, nobles, and other knights. In this instance, these princes were no more than primi inter pares. This impression is in sharp contrast to the Bellenville and Gelre armorials, both composed in the second half of the fourteenth century. Here, the ducal and comital coats of arms are depicted four times the size of their vassals’ shields. In the Bergshammer armorial, made around the middle of the fifteenth century, the composition was yet again different. The arms of Philip the Good (the duke of Brabant) introduce the first page of the marche of Brabant, suggesting that this prince was of a higher rank than his predecessors as duke of Brabant and testifying to the changing position of the prince vis-à-vis the nobility (Fig. 9.5).

Similar to princely chroniclers and heralds using coats of arms to depict the numerous territories of the Burgundian composite state, urban writers, too, explicitly linked their city’s heraldic sign to the municipal territory. Firm in the belief that his hometown had been founded as a Roman colony, the Augsburg chronicler Hector Mülich (d. 1490) began his history of the city thus: ‘Drusus, a Roman, was the stepson of Emperor Octavian. He built a wall for the city of Augsburg, and he gave it its shield of arms.’35 The city’s walls, symbolising Augsburg’s urban identity as a community distinct from the rural countryside, were closely linked to the municipal arms as another foundational element of Augsburg’s history. The same was achieved visually in a depiction of Augsburg’s skyline in Hartmann Schedel’s Liber chronicarum (1493), which shows the Augsburg arms above a town gate.36 In fact, this chronicle features a considerable number of woodcuts of other late medieval cities (e.g. Cologne, Nuremberg, Metz, Nicea, Padua) which are conspicuously identified by a prominent display of municipal heraldry on their distinctive fortifications.37 In chronicles written in the county of Holland in the last decades of the fifteenth century, even the city walls and towers of Troy were adorned with the coat of arms of the counts of Holland, which was supposedly the same as that of their Trojan ‘predecessors’. Princes and nobles loved to entertain the idea that they descended from ancient heroes like Hector, whose son Francus was supposed to be the mythical progenitor of the Franks.38 Heraldry in manuscripts thus allowed both cities and princes to boast about the ancient roots of their territory and/or their family, connecting their most visible signs to a mythical past.

Material Culture

These textual reference and artistic depictions are representative of the role heraldry played in representing territory in everyday life—how coats of arms ‘signed’ spaces, as Laurent Hablot puts it.39 As Schedel’s Liber accurately depicts, coats of arms often featured on the fortifications of pre-modern towns. That the gates of Augsburg, for example, were painted with the municipal arms follows from expenses recorded by the city in 1396.40 Here, they marked the urban territory and put a ‘stamp’ on the urban defence system; even in an urban context coats of arms thus remained closely connected to the military sphere. But the presence of coats of arms on these sites of urban defence also reinforced the territorial connotations of the signs themselves. After all, town gates provided the central liminal threshold of the fortifications which circumscribed and established an urban space its inhabitants perceived as fundamentally different from the outside world.41 This significance of the urban fortifications also explains why so many municipal coats of arms incorporated these symbols of urban autonomy into their iconography.

Furthermore, like their princely counterparts, towns were able to show off the extent of their own, communal possessions by means of heraldry displayed on urban architecture. Just as the dukes of Burgundy combined the different coats of arms of their possessions in a single shield, the town of Erfurt showed off its purchased extramural possessions by adding their corresponding coats of arms to its shield.42 This quite complex arrangement of quarterings testif ied to the increasingly extensive possessions of the urban community and was proudly displayed outside the late medieval town hall, where the town’s municipal arms are framed by the coats of arms of the hamlets of Kapellendorf, Vippach, Vieselbach, and Vargula.43 These stone carvings closely resemble the four quarters displayed by noblemen in similar iconographic settings meant to evoke at least four ancestors as ‘proof ’ of their nobility,44 but with a much more distinct territorial implication.

Of course, emperors, kings, and princes were equally keen to represent their possessions by means of heraldic communication, as not least the example discussed in the introduction has shown. The territorial structure of the Burgundian-Habsburg composite state was visible to a wider audience in a range of different media, notably the stained-glass windows the duke installed in his palaces and residences, or donated to churches and monasteries. The financial accounts of the Burgundian and Habsburg princes reveal that they donated at least 150 stained-glass windows to churches and convents in the Low Countries between 1419 and 1519.45 The initiative of donating stained-glass windows was never exclusively a princely matter, but depended on the material needs of the churches and how they could com-municate these needs to the ruler.46 In 1454-1455, for example, Duke Philip the Good donated a window to the church of St Nicholas in Amsterdam. Since a new choir was built in exactly those years, it is most likely that the church wardens had approached the duke for a material contribution. The window depicted seventeen coats of arms: four personal, quartering Philip the Good’s four grandparents, and thirteen coats of arms reflecting the titles of the duke, most of them territorial, others less so.47 Although it is important to remember that such extensive heraldic representations were only possible when the duke had a relatively large window at his disposal, similar displays existed in the churches in Brussels, Ghent, Lille, and Dordrecht. In this way, the duke publicly displayed his devotion and contributed to the maintenance and splendour of the building, whilst appealing directly to the loyalty of the citizens and reminding them of the composite state of which they were part.

The kings of the Jagiellonian dynasty, who ruled large parts of Eastern Europe, were equally concerned with the heraldic representation of their territories, again especially after their death.48 The pedestal of the canopied tomb of Władysław II Jagiełło (r. 1377-1434) in Cracow’s Wawel Cathedral is occupied by the four shields of the lands united by his crown, namely Lithuania, Poland, Greater Poland, and Wieluń and Dobrzyń (Fig. 9.6).49 Wladyslaw II had inherited the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from his father in 1377 and gained the crown of Poland through his marriage with the heiress Jadwiga; the lands of Wielun and Dobrzyn were integrated after the Battle of Grunwald of 1410 as separate entities within the kingdom.

Other masters of such territorial representations by means of heraldry were antagonists of the Jagiellonians, namely members of the house of Habsburg. They often relied on the sheer number of territories represented by their coats of arms to inspire awe in passers-by.50 A painter in the employ of Emperor Maximilian I (r. 1486-1519), Jörg Kölderer, explicitly noted that he had been charged with ‘painting on parchment all the lands of his majesty, that is shields, helmets, and crests’.51 Among Maximilian’s precursors was Rudolf IV, duke of Austria (r. 1358-1365), who, like the Polish king, heraldically showed off the territorial reach of his rule over Carinthia, Styria, Habsburg, Mark, Carniola, Pordenone, Burgau, Kyburg, and Rapperswil on a magnificent seal.52 His grandnephew Frederick III, as German emperor, followed in Rudolf ’s footsteps: vast territorial possessions were implied by a ‘wall of arms’ part of the chapel of the Habsburgs’ castle in Wiener Neustadt, Austria. Erected about 1453, the wall was adorned with stone carvings representing a total of 107 arms, taken from the aforementioned Chronicle of the Ninety-Five Lordships. Apart from the fourteen coats of arms of the house of Habsburg’s actual Austrian principalities, the wall showed the (attributed) arms of the legendary kingdoms which had supposedly existed on the Austrian soil in time out of memory.53 In this way, this material display, too, presented the Habsburgian possessions as rooted in the past, hence legitimizing the rule of the dynasty over these lands.

A similarly extensive (and similarly cryptic) heraldic representation of the house of Habsburg’s territorial domination was inspired by such architectural landmarks, namely the monumental Triumphal Arch designed for and partly by Emperor Maximilian.54 It seems that this arrangement was

never meant to be executed in any form other than woodcut prints, possibly intended to be reproducible wherever the emperor happened to travel.55 The arch must have been meant to serve as an ad hoc piece of Habsburgian self-aggrandisement which offered a plethora of dynastic and imperial symbolism – not least in the form of heraldry – to any audience, regardless of whether they were able to recognise individual coats of arms, or whether they were simply awestruck by its sheer size. Certainly, the makers of the arch drew on a long tradition of similarly short-lived decorations meant to convey notions of the vast and widespread possession of the dynasty by means of heraldry, especially during Joyous Entries in the towns of the Habsburg composite state.56

Heraldic Performances and Contested Territories

Joyous Entries point to a less permanent and more ephemeral, performative side to the representation of territory through heraldry, which was deeply involved in representing, establishing, and challenging claims to territorial possessions. Towns and cities – the ‘public spheres’ of the Late Middle Ages57– proved particularly prominent stages for this kind of ritual which served the delicate double function of acknowledging the entering ruler’s legal authority whilst preserving and sometimes even extending the city’s privileges and liberties.58 Urban governments and institutions, notably guilds, were in charge of such displays and certainly up to the challenge, as the creation of elaborate heraldic programmes shows.59 In the Burgundian Low Countries, like elsewhere, gates, streets, and numerous tableaux vivants were adorned with coats of arms of ruler, town, and principality, ready to be seen by the visitors and urban crowds alike; not only were urban writers and painters expected to ‘speak’ the ‘language’ of heraldry, but this sign system was also aimed at a relatively large and apparently heraldically knowledgeable urban audience, not least for the communication of territorial messages.

During the entry of Maximilian of Austria in Antwerp in January 1478, for example, the guilds had set up ‘a tree with seventeen branches with shields of the seventeen lands which our princess [Mary of Burgundy, Maximilian’s bride] had inherited from her father, Duke Charles’. Apparently, in the eyes of Antwerp’s citizens their polity now transcended the borders of both city and the Duchy of Brabant. What is more, in another tableau they connected the heraldry of the Duchy of Brabant to biblical imagery: beneath the throne of God the four Evangelists featured, with Mark shown as ‘a golden lion with a shield quartered with the four lions of these lands’, that is the quartered arms of Brabant and Limbourg, which were part of the arms of Mary of Burgundy (r. 1477-1482, see above).60

When Maximilian came to Nuremberg in 1489, the townspeople’s embrace of his rule was equally territorial in nature. Children lined the streets, ‘each holding a pennon which depicted, on the one side, an eagle with one head and Austria [Habsburg] in the centre, and on the other side a shield of his lands, of which he has 24’.61 The same had happened at his father Frederick III’s quite similar reception in 1471, when children from local Nuremberg schools greeted the emperor with ‘a pennon painted with the emperor’s lands in each of their hands’.62 Territorial heraldry also embellished the canopies under which the cherished guests were led through the streets of the city, usually borne by the most influential urban representatives: when King Sigismund of Luxembourg (r. 1411-1437) entered Speyer in 1414, a canopy ‘of a yellow colour and with a black eagle’ also showed ‘the arms of the Empire, Hungary, and the prince-electors’ on its fringes.63 Reminiscent of the Holy Roman Empire’s ‘constitutional’ elements expressed in the Reichsquaternionen,64 this arrangement of multiple heraldic signs closely resembled the ensemble of Habsburg territories represented on pennons in Nuremberg. Once again, the composite character of the Habsburg state was communicated both ways – from town to ruler and from ruler to town – showing that both parties were acutely aware of the specific territorial configuration of which they were part.

Parallel to such coordinated representations of territorial possessions, on the level of the individual sign in relation to the surrounding space, heraldry was also involved in the communication of concrete claims to power over the city. When towns in the Holy Roman Empire were conquered by ‘predatory’ princes, frequently the conqueror removed the arms of his predecessor from symbolic sites of urban self-government, notably the town hall and the marketplace.65 After Louis IX of Bavaria (r. 1450-1479) had conquered the imperial city of Donauwörth in 1458, for example, the duke not only replaced the members of the town council with men more faithful to the new lord, but also substituted the symbols of imperial sovereignty with those of ducal rule: ‘The arms of the Empire were struck down from all gates and from the town hall, and [instead] the arms of Bavaria were painted there.’66

Charles the Bold was another expert in such heraldically communicated territorial claims. During his military exploits, the objects of his territorial ambition were often conspicuously marked by means of heraldry, as a Swiss chronicler knew all too well: ‘The reason why the duke of Burgundy always carries a large number of flags and signs with him […] is that so whenever cities or lands are conquered […] numerous Burgundian banners can be erected and unfurled so that they scare and frighten the people, as happened in Ghent, Liège, Dinant, and other great cities.’67 These three towns had rebelled against the duke’s authority, and apart from material punishments (the closing of a town gate, the demolition of the town walls), they had to face the clear and daily visible heraldic submission to his rule, too.68 In April 1474, the council of Cologne similarly complained about the ‘putting up of arms’ (‘upslayn der wapen’) by Charles’s men, and shortly afterwards, in June, Pope Sixtus IV himself admonished the duke to cease ‘affixing your arms to the castles and places of the said diocese [of Cologne] or hanging your banner therefrom’.69

Such heraldically staked claims to authority or even possession of territory were not always left unchallenged. After Charles the Bold had ordered a herald to distribute his personal coat of arms in Cologne, the townspeople rejected this visible claim to their city with an attack on the very same heraldry: ‘The common men gathered in all places where the duke’s letters and arms had been put up, hurled faeces and other muck at them, ripped them off and dragged them through the dirt, shaming the proud prince […] as much as possible.’70 Similarly, if conquered towns were, eventually, reconquered, the restoration of the heraldic status quo ante was an important measure. After the aforementioned town of Donauwörth was recaptured by imperial forces in 1459, the heraldic changes imposed by Louis IX were reversed, rejecting the territorial claims of the duke and restoring of imperial sovereignty over Donauwörth: ‘People removed the arms of Bavaria from all gates and the town square, and once again painted the arms of the Empire there.’71 The same was the case when cities overthrew disagreeable lords themselves, as was the fate of the de facto rulers of Florence, the Medici family, and their coats of arms in 1527: ‘Not only were their arms displayed in holy places removed, but in fact all arms of that noble family, whether they were hung on the doors of private families or inside some public building, were torn apart or set on fire.’72 Thus, coats of arms were not only displayed in space, but were seen as powerful symbols that shaped space, hence influencing the way territory was perceived by a large audience.

Conclusion

This essay has shown that, in the Late Middle Ages, heraldry served important communicative purposes in relation to territory by representing, reinforcing, and constructing claims to authority in space. Individual coats of arms first gained territorial associations in the context of warfare: placed on banners, they became associated with the land of the fief that mustered the troops, and as fiefs moved through inheritance (often through [heraldic] heiresses), investiture, sale, or conquest, so too did the coats of arms associated with the land. Princes, noblemen, and cities chose to combine their established coat of arms with the arms of newly acquired possessions, thus creating a complex visual shorthand for the entirety of territories in their possession. This approach was particularly useful for composite states such as the Burgundian Low Countries, though of course it also lent itself well to ambitious princes who wished to lay claim to lands by appropriating their coat of arms, as Edward III of England had done,73 to name another famous example. Heraldry was a capable and space-efficient solution to the problem of communicating the nature of territory to a large audience; it allowed the conveyance of a spatial claim tied to a coat of arms just as it allowed for the compact representation of complex territorial configurations by combining multiple arms in a single shield.

Sometimes such heraldic representations also had to satisfy the desires and ambitions of the local and regional elites and other powerbrokers who had to accept claims to territory or required integration into the new composite state.74 A wide range of media was available to serve these purposes. Manuscripts such as armorials and chronicles curated these complex territorial structures (real and imagined) and thus allowed the tracing of their historical development over time, just as the appearance of heraldic seals ref lected such changes. Architecture, from palaces and churches to town halls, displayed heraldic representations of territories as well, and the same was the case for tombs and monuments. Finally, there also was a performative dimension to the representation of territory by means of heraldry. Joyous Entries saw the display of territorial arms and heraldic arrangements of various possessions. Likewise, similar to individual signs used to demarcate urban spaces displayed on town gates, coats of arms were put on display (or destroyed) to stake (or reject) new claims to authority over space, as in the case of Charles the Bold’s campaigns.

If we want to write a history of territory in the late medieval period which looks at territory ‘not simply as an object’ but as ‘a process, made and remade, shaped and shaping, active and reactive’, as Elden highlights,75 then the role of visual communication in general and heraldry in particular emerges as a key component to study. In this sense, this essay echoes important methodological developments in the discipline of heraldry, which is currently moving away from ‘traditional’ approaches to coats of arms, focused on their connoisseurial appreciation and antiquarian uses as identifiers of their bearers,76 towards approaches inspired by cultural history.77 From this perspective, heraldic signs emerge as a versatile and ubiquitous phenomenon of late medieval visual culture. They were deeply involved in the representation, negotiation, and construction of social and political structures – not least with regard to the communication of authority in space and thus the creation of territory.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 9 (245-276) from Constructing and Representing Territory in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, edited by Mario Damen and Kim Overlaet (Amsterdam University Press, 12.08.2021), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.