‘Home’ was central in ancient Greece.

Looking for a Family

By Danielle Szymezko-Singer

Occasional Teacher

District School Board of Niagara

For Classical Athenians, the family could mean a variety of things. According to author Janet Morgan, the typical Athenian family was very similar to what we in North America call a “nuclear family”. A “nuclear family” is considered a family with parents and children. Whereas the most common type of family in Athens consisted of the husband, wife, and children, it also included the possibility of enslaved workers, whose numbers depended on the wealth and status of the household. Although the most common type of family, this was not the only type of family household that we come across in that era. Trials in the Athenian courts reveal that a variety of family arrangements were possible. In Lysias 3.6, for example, the speaker lives with his sister and his nieces. They are still a family but do not fit this “nuclear family” model that we have in our minds. An example of another type of family is in Demosthenes 57.40 where we are introduced to the idea of stepparents, remarriage, and half-siblings. Families even included adopted members, but whereas adopting newborns is common in North America today, the adoptees were young adults (often a nephew) who could keep the oikos reproducing and its wealth intact.

As diverse as the families could be in classical Athens, they each had a very similar family dynamic. Different members within the household were responsible for different duties and jobs both within and outside of the oikos. These duties were typically distributed based on gender and status. In Xenophon’s Oeconomicus 9.2-10, we see the husband and wife in a discussion of how their household would be run, both inside and out, with the assistance of enslaved workers. First, we have the husband or the eldest male within the household. This individual was considered the “manager” of the household and he would not typically partake in performing household duties himself, unless from a lower-class family. He would, instead, dictate to his wife, and enslaved workers what tasks within the household they were responsible for. He would also train his wife to fill his role as supervisor of enslaved workers within the house. In doing so, he expected his wife to act towards these workers the same way he would and to reward and punish them as appropriate. Next, the text details the wife’s role within the household. The wife typically performed household duties such as cooking, cleaning, and weaving, often working alongside the enslaved workers. As previously mentioned, she was also responsible for managing the enslaved people working inside the household while her husband was absent. In this text, she has important responsibilities, but is like an assistant to her husband and is expected to defer to him on any issue. In less wealthy families, such strict gender roles were not likely possible in the running of the household, but a wife’s obedience to her husband would still be expected.

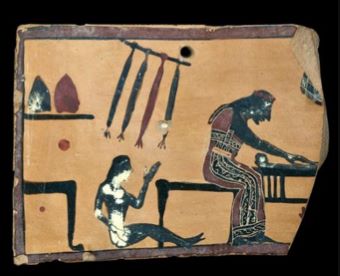

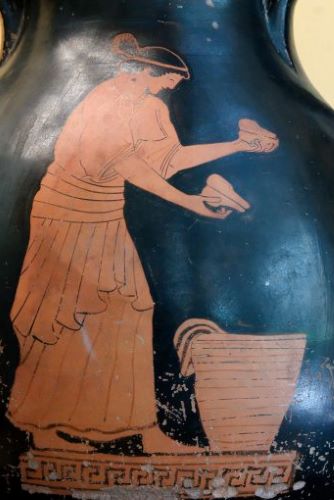

Next, we have the children. Children are not often talked about in written sources, and it is difficult to find material evidence of their presence within the household. While young children in North America often live a carefree life with a variety of toys, Athenian children did not. Athenian children often spent the majority of their time accompanying their parents, learning the duties that they would have to perform as adults, both at home and when they were married and had started their own families. Pictured here is a painted plaque which is depicting a scene of a young girl accompanying presumably her mother and watching her do some weaving. According to Plato (Laws 1.643c) children were encouraged to develop skills for their future working lives by playing with miniature versions of these tools.

In contrast to modern-day North America, children were not immediately considered a member of the family once they were born, regardless of their parents’ status. When a child was born, the head of the household was responsible for inspecting the child and validating the child as a member of the oikos. After this took place, on the fifth or seventh day after birth, the Amphidromia was held. The Amphidromia was a religious event where the family would make a sacrifice to the gods and the father would walk around holding the child up in the air to indicate his acceptance of the child into the household. Afterward, they would have a small feast where only the family or anyone who was present for the birth attended. On the tenth day after the birth, depending on the wealth of the family, they might also hold a dekate, which was more of a festive event where they held a feast, with entertainment for family and friends, in the celebration of the birth.

Children were also seen as a representation of their family’s thoughts, ideals, or beliefs. Athenians would often have their child’s personal name be representative of something important to the family. Mark Golden discusses how a common name for young boys was Hegesistratus or Hegesias for short. This was indicative of a militaristic family as it meant “army leader”. He goes on to explain how these speaking names allowed parents an opportunity to express opinions on political matters, as well as mold their children’s sense of self. This would also indicate the values of the family and the broader community that they lived in.

As previously mentioned, children often played with tools that would help them to develop skills that they would need to perform tasks later on in life. It has proven difficult, however, to establish what was considered to be a children’s toy from what was considered an item used in offerings, either for the gods or for ritual practices. This fact has also makes finding evidence of children within the household through the archaeological record difficult. For instance, Joan Reilly makes mention of terracotta dolls that were discovered in excavations and sometimes depicted on tombstones, but they were not your typical “Barbie” type of doll. Instead, as pictured to the left, these dolls were anatomical votives. It was believed that these votives assured that the young girl would hold a healthy female body that was capable of reproduction. Therefore, what we may consider to be toys, was not a toy to Athenian children. This observation makes it extremely difficult to find evidence of children archaeologically but also shows how their lives went beyond the carefree lifestyle which children in North America have today.

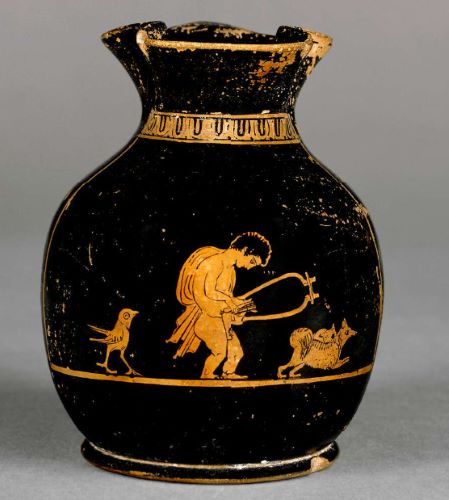

Pets, including dogs, cats, and birds, were also important members of the oikos. In Classical Athenian art, we see two types of dogs depicted. One breed is considered “hounds”. These dogs would often accompany the men on hunting activities where they would help attack and take down the animals. The other breed was Maltese dogs. The Maltese were what we might consider lap dogs and household family pets. They were normally depicted accompanying and playing with young children and women, as seen on this red-figured chous. Archaeological evidence also reveals that families sometimes honoured dogs with burials, suggesting a close bond between families and their pets as well as grief at their loss. Pets appear to have been as important a family member to Classical Athenians as they are to us in North America today.

The concept of family, what defines a family, and who was considered a family member was very diverse in Classical Athens. Although a family was more commonly classified as our modern-day “nuclear family”, there exist many examples in the sources showing that a family was also much more than that. Overall, though, the family dynamic and roles within the household were affected by gender and status.

From the Ground Up

By Basil Tabes

Graduate Teaching Assistant

Brocks University

The ancient Greeks have been revered throughout history for their extravagant monumental architecture. The production of domestic structures, however, is often overlooked. The household was the base of Greek society, and one can not have a household without the house itself. As magnificent as they are, temples and theatres are not suited for people to live in. The construction of houses in Classical Greece did not differ significantly from the modern era, and much of the process is still actively used today.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of Greek houses have been reduced to just the foundations over the millennia, meaning that much information regarding the construction of the house remains unknown. Luckily, there are extant written sources that help paint a picture of what these buildings would have looked like when they were inhabited. The philosopher Aristotle offhandedly mentions the management of balcony measurements in his Athenaion Politeia (50.2) and other features that have been completely lost in the archaeological record. Despite living hundreds of years later, the Roman architect Vitruvius wrote down his observations on how the Greeks built their houses in his De Architectura (2.8.5), providing us with the most detailed descriptions of Greek domestic architecture.

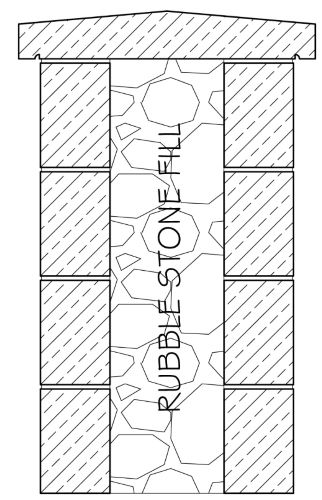

The average house in Classical Greece was made out of relatively simple materials. The typical house had a foundation utilizing stone as the main component. One of the most common methods of foundation construction was rubble masonry. Relatively small, irregular stones were gathered and stacked into a wall, and may have been cemented with mortar to ensure they remained in place.

The other most common type of masonry was ashlar masonry. This type of masonry consisted of carved stone blocks tightly arranged in neat rows. These blocks varied in size, ranging from the size of a brick to massive slabs. These were most commonly carved out of limestone, which was often gathered from a nearby quarry. In situations where there was no nearby quarry, or if the builder desired a higher quality material, stone was imported from outside sources. Out of these two, rubble was the more cost-efficient method since it required less labour to produce by using debris instead of hand carved stone.

The walls that sat on these foundations were most commonly made of mudbrick, a material still commonly used today (Adobe is a common example). Mudbricks were comprised of a mixture of soil, sand, and water that were then pressed into blocks and left to dry in the sun. In many cases, the bricks were strengthened by the addition of straw into the mix, or were fired in a kiln to produce a stronger material. Although it was inexpensive and versatile, mudbrick was not nearly as durable as stone, and often had to be supplemented with stronger materials. In this case, the bricks would be arranged in two parallel lines with a hollow in the middle, which would then be filled up with stone debris (and sometimes mortar) to make the wall sturdier. Wooden beams would often be inserted in these walls and covered up to provide support while also keeping the space open.

Like with many of their temples, the roof of a house was covered in overlapping terracotta tiles. Terracotta roofing acted as a midway point between the earlier materials, lightweight but weak wooden/thatch coverings and the sturdy but heavy stone tiles. This allowed the Greeks to create larger, more open structures while also maintaining a high degree of insulation and protection.

Plaster was one of the most important materials in the ancient world. Made from a combination of powdered lime and water, plaster served a multitude of purposes. Once the structure of a house had been built, the walls were most often then covered in a layer of plaster. The main purpose of this is to act as insulation, creating a solid layer around the walls. This protected the mudbricks from damage that would be inflicted by water, weather, or being struck, allowing the walls to go longer without need of repairs. Plaster was also popular for its use as an artistic medium. While most of the time the plaster was left bare, it was common for artists to paint frescoes on wet plaster. A famous later example of this technique are the frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. Painted plaster is more common in wealthier houses, as the upper classes would be able to afford artisans.

When thinking of what a wealthy person’s house in ancient Greece would look like, most people might imagine a massive, luxurious country villa. While these certainly did exist, for the most part wealth did not play a significant role in the size of houses. Many houses, especially in heavily urban areas like around the Athenian agora, were all roughly the same size.

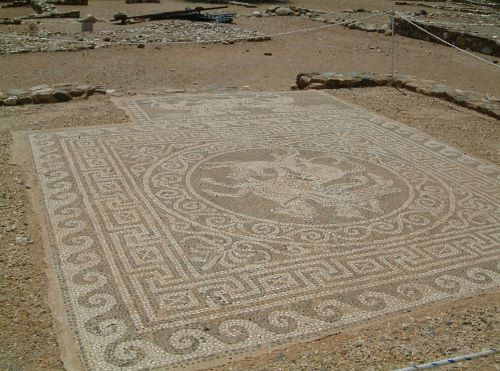

As the houses themselves were all relatively equal, wealthy members of society had to compensate with interior decoration. This would often be done with elaborate artwork, such as plaster paintings, stone carvings and mosaics. For example, mosaic floors depicting scenes from Greek mythology have been found at the site of Olynthus, something that would have distinguished the owners as being wealthier than the average family, who would have had simple bare floors. Since social image was an important part of Greek society, wealthy individuals would make sure to beautify the inside of their homes to flaunt their status to any guests.

Once all the materials were gathered, the house actually had to be put together. There are few sources describing the actual construction process, but from what has been found we can divide the people involved into two broad categories. There were the general labourers and the specialists. The actual building of the house fell on the general labourers. These were people who put the entire structure together, similar to modern construction workers. Specialists were more extensively trained in a specific field. For example, while the house was built by a general team, there may be a few people who are well versed in the creation of drainage systems, or a professional stone carver.

While room use in the Greek household was very flexible, certain rooms required permanent specifications in order to be used properly. For example, floors of designated bathrooms would often be waterproofed with a thick layer of plaster. Fixed hearths, while not as common as portable braziers in the Classical period, were built directly into the structure itself, and therefore required extra specifications. Chimneys then had to be built into these rooms to prevent smoke buildup.

Organization of Space

By Alex Hoffer

How domestic space is organized is something that can be used to distinguish societies from one another. Functionality and style decisions affect the arrangement and use of space and can certainly be seen in design and organization choices in homes in North America today. For example, shag carpets and walled off spaces indicate older design choices, while open-concept homes indicate the home was built more recently. The evolution of Greek houses, from larger, generalized spaces towards much more segmented, and specific rooms, signified a different and new level of organization in the household.

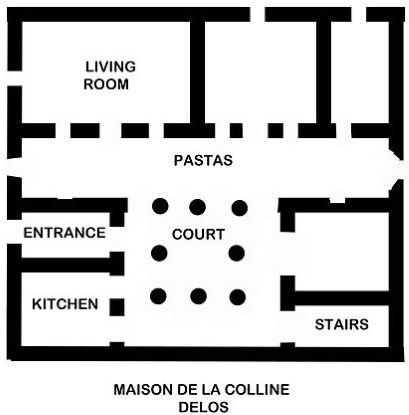

When discussing the houses of classical Greece, archaeologists typically classify them as ‘oikos’ or ‘courtyard’ houses. These style of houses feature a pronounced courtyard within the central area of the house, suggesting its high usage in the day-to-day activities of the household.

This drawing shows a ‘typical plan’ of a courtyard house with a single entrance into a courtyard onto which the rooms open. The inner courtyard design emphasizes household privacy. While a living room and kitchen are labelled, activities associated with these spaces were not restricted to that area of the house alone. What is important to note about this layout, however, is how segmented the space was, using mostly doorways instead of natural openings.

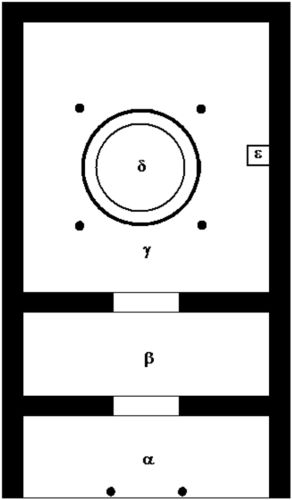

This plan can be contrasted with an earlier layout of the Greek home, called the ‘Megaron’ style house. Its organization of space is very linear compared to the courtyard house and leads to an open and fully universal space. With the early iron age Megaron houses, there was no subdivided space, so there was really no way to divide out activities within the home. This is in contrast to the courtyard home, where its segmentation could allow for more specific work being done in a given space.

An important element to understand about this change in the way the buildings were built and organized is the concept of ‘societal complexity’. As Greek society developed (from the eighth century BCE onwards), so did the various elements of everyday life. The change was based on a hierarchy of need. An example of growing complexity in the classical Greek household plan was the andron, a space used primarily for leisure. The major necessities of life, food, shelter, etc., which were the focus of the most basic Greek home, were now being added to.

Archaeological evidence is the main source of what we know about how homes were spatially organized. Since many building materials were not able to stand the test of time, such as wood and mudbrick, it can be difficult to determine how internal space was divided and organized in some areas of the home. This scene from an Attic vase shows that columns could differentiate space and it is possible that wooden partitions or even fabrics would also be used to further divide up space. Houses at Olynthus, furthermore, have evidence of stairways to a second floor. The more open and generalized space is easier to interpret, while the complex organization of the courtyard house makes it harder to truly conclude what happened where, especially in structures with two stories, since all their rubble would still end up at ground level.

It is not through architecture, but through a close examination of finds that room use can be reconstructed. The varied locations of the objects found in different homes, such as stoves, braziers and loom accessories, show that Greek society did not have an agreed upon way to designate household space. What is extremely important to understand about these items is that the majority of tools and products, including stoves and ovens, were created to be as portable and mobile as possible. Their portability allowed those working in the house to enjoy warm, sunny days by cooking or weaving outside in their courtyard, or cooking near a dining room to conveniently entertain guests while also preparing a meal.

An important element of organization in the home was how items were stored, specifically cooking appliances, cutlery and plates. Broken plates and bowls, for example, can be found in the fixed kitchen area but also around the house where there was less evidence of long-term cooking being done. Archaeologists speculate that they used fixed cupboards similar to ours, but also had portable carriers of items that they could move to wherever the cooking instruments were set up.

A question that interests archaeologists and historians is how gendered activities were organized. Literary sources suggest that there was an area of the home designated for women, a gynaikonitis (women’s quarters, e.g. Lysias 3.6-7). The more segmented homes would surely seem to indicate that there was a cultural need for segmentation in some capacity and one reason may have been to keep women separate from men. But the literary evidence contrasts with the material evidence. Not only are tools used in ‘female’ activities, such as weaving tools and cooking appliances, found in designated areas in the house (which could be labelled ‘kitchen’, ‘work area’, etc.), but they are also found in communal areas of the house, like the courtyard.

The courtyard house was able to offer much more specialized spaces and by many accounts did. Women’s spaces would include the cooking space and other domestic labouring spaces (such as for weaving, etc.), while men’s spaces would include an andron and other recreational spaces. But we can see from visual evidence on vases, as well as written accounts, that female entertainers were invited into the andron space during symposia, meaning that the room’s ‘men only’ policy was geared towards the women who lived in the house, as well any wives or daughters of the guests. In addition, evidence of the activity of women appears throughout the house. Gendered space seems to be much more of a suggestion than a concrete area where a given activity must be done. Overall, one can see that there is some confusion in the evidence around the use of gender to divide the house into various spaces. The increased number of different spaces was not a result of subdividing spaces based on gender. Time of day, for example, would have been an effective way to divide up activities and keep men (especially non-kin males) and women separate.

What should be apparent from this chapter is the dynamic utility of the rooms in the Greek house. The dedicated use of a certain room was arbitrary and the space itself not fully representative of what the room might have been used for in the home. It’s important to emphasize that there were many variations in how the space was used, often tailor made to the needs of the inhabitants. Space was commonly multipurpose and flexible. What is consistent between houses is the focus on privacy and the multifunctional use of the courtyard.

The Andron

By Ashley Rydzik

Humanities Major

Brock University

The andron: a place where Greek men wined, dined, and socialized during an event called a symposium. In many ways, a symposium could be considered similar to what we refer to as a ‘house party’ today – people get together, consume food and drink, listen to music or another form of entertainment, and socialize with one another.

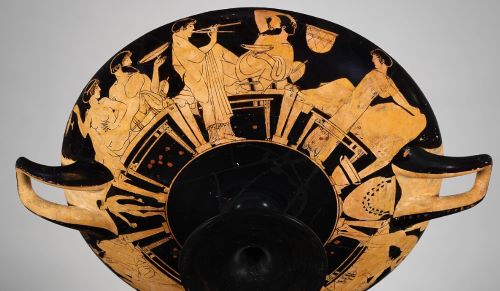

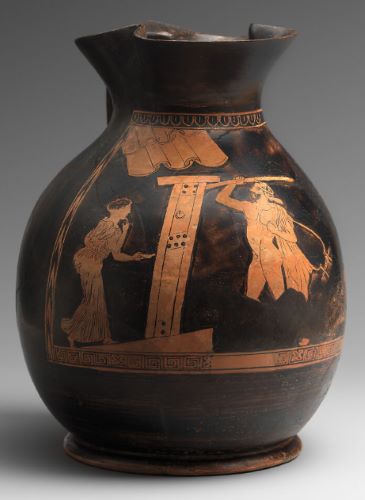

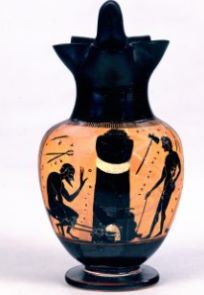

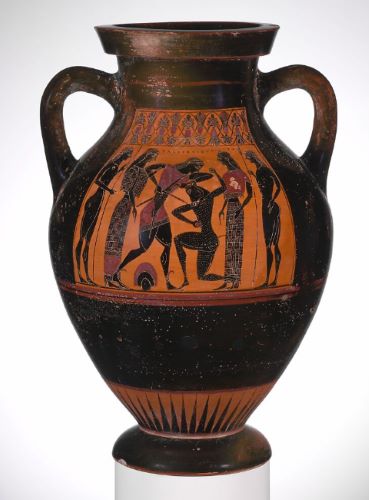

There were even times during symposia when men would drink too much wine (the primary beverage consumed at these events) and make themselves sick – a feeling that is all too familiar to many at a house party. An ancient representation of said debauchery is depicted in the vase painting shown on the left. Although parallels can be drawn between symposia and house parties, there are several stark differences, especially when discussing the gender division of the andron. This chapter will explore the andron and the symposium, and will answer questions regarding the function and organization of both.

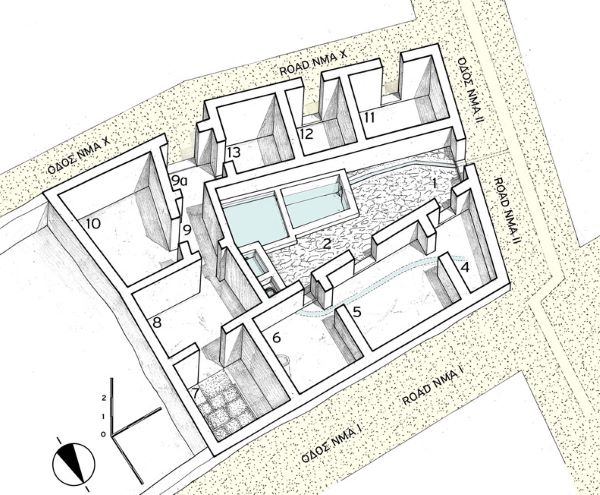

The andron was a room found in some, but not all, Classical Greek houses. Architecturally, this room is often identified by its square shape and raised cement borders, which presumably held the klinai, the couches that guests reclined on during symposia. Pebble mosaic designs sometimes adorned the middle of the floor, such as the mosaics found in rooms at the Villa of Good Fortune. The andron was largely separate from the rest of the house, often with an antechamber preceding its entryway and an offset door.

This design was thought to be done to ensure that women were completely separate from the events that took place in the andron and to prevent them from seeing or interacting with those who were attending a symposium. It supports the concept of separate gendered spaces for men and women in classical Greece. See, for example, House Θ to the right. In this house’s grid plan, room 7 is thought to be the andron, with room 8 being the antechamber. Scholars think room 7 to be the andron because of the raised cement borders and mosaic tiling that remains. The image at the bottom of this page shows the actual remains of House Θ from one of the exhibition areas at the Acropolis Museum in Athens. It is important to note that although all androns may have had the same function, they certainly did not all look the same. Discrepancies between androns can likely be attributed to status, as the wealthy would have been able to better adorn their space than poorer citizens.

So, what did an ‘average’ andron look like, and is it possible for us to identify it in the material record? Literary sources, such as Lysias’ On the Murder of Eratosthenes (1.9), describe the andron as a flexible, rather than a permanent space. These texts suggest that the andron, and its symposium (the main event that took place in the andron) were portable, and did not necessarily have to take place in a designated area of the house. Lysias’ work demonstrates this well as Euphiletus is able to move his andron upstairs when needed. A fairly common conception is that the andron and symposia were only for wealthy, elite men. The above evidence, however, offers an alternative idea – that ‘average’ androns existed, but they just did not survive archaeologically because of their temporary nature (compared to the more structural permanency of elite, cement-bordered androns).

The literal meaning of andron is “of men,” implying that the andron was a space for men only. But androns were likely multi-functional spaces as is hypothesized for the rest of the Classical Greek house. Thus, the andron was not simply used for symposia (male drinking parties), but rather had different uses at different times dependent on need. Androns could even be used by women for household activities such as weaving, which is evident by the presence of loom weights in typical andron rooms at Olynthus. Additionally, we know that during symposia it was not solely male citizens who were present. Enslaved people, entertainers, and prostitutes, many of whom were female, played a key role at symposia, although one that was much different from the elite men hosting and attending the event. Men and women did not have the same status and rights in ancient Greece, especially not the women attending symposia as they were not deemed “respectable.” They could be forced into sexual submission with impunity – a sad reality that is often overlooked when studying ancient symposia. Such violence is what the famous sex labourer Neaira experienced when she attended a victory party with her lover Phrynion ([Dem]. 59.33-34).

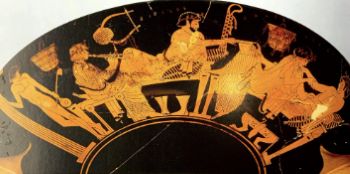

The symposium was the fundamental social institution in ancient Greece – particularly in Athens. It consisted of a small group of men convening in the house of a friend for an evening of drinking; there may have been a meal beforehand as well. The men reclined on couches, sang, told stories and philosophized, and gazed at the hired entertainers, as can be seen in the depiction of a symposium on the drinking cup to the left. Said entertainers ranged from musicians and acrobats to hetairai – trained sexual companions. But the importance of the symposium did not lie in the event itself, but rather the overall atmosphere it produced. Communal drinking activities were intended to forge and emphasize group identity – a concept that was as crucial to democracy in classical Athens as it had been among the aristocracy of archaic Greece. The change to democracy saw the coming together of people from all over Attica and from all walks of life, and so establishing a collaborative social environment among the citizen men was essential – and the most acceptable way to do so was through drinking.

The drink of choice was wine mixed with water in a large mixing vessel called a krater. Mixing was done in order to ensure the symposiasts maintained their composure and self-control – traits that were highly valued in ancient Greek society. It was believed that only uncivilized peoples drank unmixed wine, and the Greeks thought themselves to be much better than their non-Greek counterparts. But were the Greeks really any better? The dilution did not keep the men sober as they consumed on average between 4-5 kraters per night. Thus, evenings often ended in drunken debauchery, with symposia often getting out of hand and leading to destruction of property and injuries. This is discussed briefly in Plato’s Laws, as he describes how excessive drunkenness, such as occurred at symposia, could lead to fighting, vandalism, and other seditious acts (1.637a-640).

The symposium itself mirrored the nature of Greek (namely Athenian) culture and society and, as politics and history affected the people of Athens, they also affected the microcosm of life in the symposium. The environment of the symposium was designed to uphold equality, just as the newly founded democracy was designed to do. There were, however, two essential, but conflicting, characteristics of Athenian society – egalitarianism (democracy) and an agonistic spirit (the desire to be the best; resulting in competition, such as at the ancient Olympics). The symposium breeds this same tension, since there was the underlying concept of equality, but also the desire to have individual recognition among one’s peers. This desire led to the incorporation of status into the ‘status-less’ environment of communal drinking, as men would attempt to show off their wealth through the luxury of their andron, entertainment, and refreshments. See for example the mosaic floor in the House Θ andron shown above, and another in chapter 2 “From the Ground Up”.

Storage

By Emily Laffin

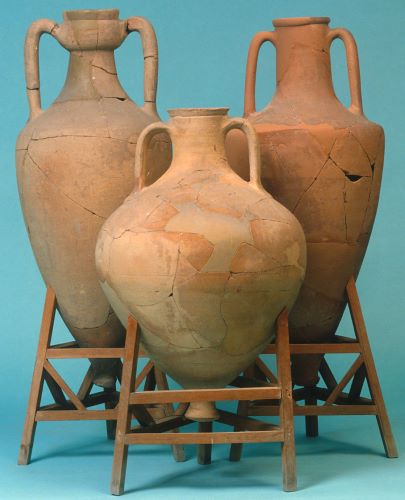

When we think about storage vessels from the Greek world, we often think of decorative and elaborate vases, and consider the images they depict more often than the actual use of the vessels themselves. For example, the decorated amphora seen and used at social gatherings would typically be used for containing and serving wine, and be decorated with a red or black figure design, often depicting scenes from mythology or other scenes that are pleasing to the eye. The typical terracotta amphora used for storage and transportation, however, features a plain and lackluster appearance with a pointed bottom. This “pointy” bottom allowed these amphoras to fit better into storage and eliminated the dangers of rolling around and breaking. While many different materials within the Greek household required storage such as clothes, jewellery, and linen, this chapter will focus on the storage of perishables, what needed to be stored, and what types of storage existed.

Storage vessels with elaborate designs and relief images were produced in ancient Greece to be used in funerary, social, and economic contexts. But rather than being inspired for such occasions, their shapes and sizes express the importance of their use for food, its consumption, and storage. Greek vessels thus had many more uses than just as art pieces. The pithos was a courseware storage vessel that had similar features to an amphora (used for liquids) with its high neck and handles, but it was often much larger in size and could store much more than the standard amphora. The basic purpose of a pithos was to store wine, oil, grain, and other types of food. Most commonly they were created from clay, which was an ideal material for keeping out water, dirt, and any outside pests. Since these vessels were intended for food storage, however, the outer appearance of the vessels was of secondary importance. Decoration was either simple or non existent. The borrowing of the amphora shape for pithoi can easily be explained by the fact that both are storage vessels, but the pithos was meant to be utilized for storage only, whereas the amphora could be formed and designed according to what its intended function would be: transportation, storage, or serving.

Was an area of the home designated for storage? Nicholas Cahill notes that most Greek houses had two storeys, and could include specialized types of rooms such as a kitchen complex, or rooms used for symposia or other purposes. This begs the question whether there may have been rooms that were entirely dedicated to food storage. Since spaces in the household were used in various different ways, it is often impossible to guess the function of a room based on material evidence alone. Cahill, however, identifies a large number of houses at Olynthus that do in fact contain facilities and rooms meant for storing large quantities of food. These storerooms are most commonly identified by the large quantities of pithoi fragments.

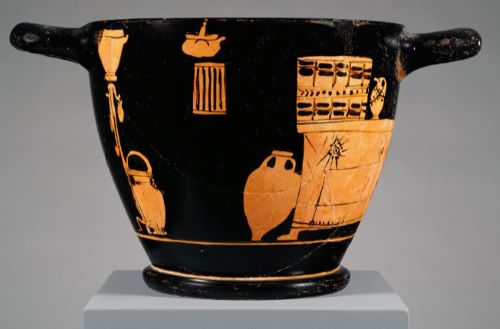

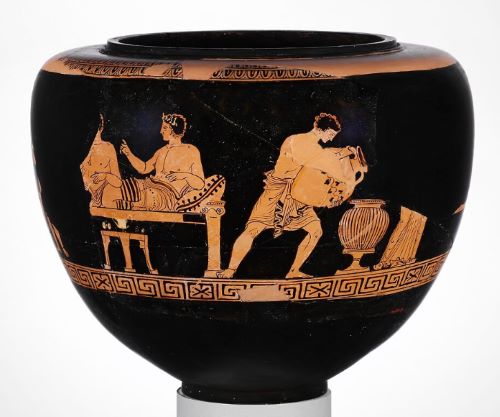

Xenophon includes a description of such storage rooms in the house of the wealthy landowner Ischomachus in his Oeconomicus (9.3). He describes dry rooms for storing grain, cool rooms for wine, and well-lit rooms for items that require light. This drinking cup depicts a general storeroom with storage vessels, including an amphora, chests, and household equipment (grill, cooking pot, drinking ware).

The quantity and length of time that food was stored is also important to consider as this would directly affect the longevity of food storage in the household, and it was important to ensure that food would not run out or go to waste. Ancient Greek farmers aimed to keep anywhere up to a year’s worth of food supply on hand in the house at any time. Since families were encouraged to sell their entire stock of grain, as noted by Nicholas Cahill, keeping only enough of a year’s supply for personal household use, it suggests that it would have been possible for them to keep more. One of the main duties of the wife of the household was to oversee this storage and attend to it, by making sure that these provisions were not used up within the span of a month. Xenophon’s Oeconomicus notes that both indoor and outdoor tasks demand labor and attention. Since the man’s body was more capable of enduring the cold and heat, he would be responsible for the outdoor tasks while the woman was much less capable of such endurance, and would be assigned the indoor tasks, which included managing food storage (7.22).

The quantity of pithoi in a household also offers hints about the use of the structure they were stored in. For example, the storage capacity of five large pithoi within the Villa of Good Fortune was too great for a single common household. The pithoi alongside other supportive evidence suggests that the villa may have been a type of hotel. The size of a storage room and quantity of on hand stored vessels also points to the wealth and status of this household, and its ability to hold stored food in much larger quantities than the average household.

Since pithoi were much larger in size in comparison to other storage vessels, they were able to serve a wider range of purposes. Most other storage was above ground, but pithoi could be dug into the ground to keep items cool below the surface. The image shown on this red-figured kylix depicts a good example of how pithoi would have been buried up to the shoulder of the vessel and provides an indication of its size next to a person.

Since the size of a pithos could be large enough to fit an entire person inside, pithoi were also used by some communities as a funerary burial vessel rather than serving its intended purpose as a food storage vessel.

There are noticeable differences in storage capacity between houses located in two different regions of Olynthus due to the adoption of different economic strategies. Homeowners with greater wealth in the so-called villa section differ from homeowners located in the north hill area. Villa homeowners invested much more space and money into their storerooms and pithoi in order to maintain self-sufficiency with their household storage. Households located on the north hill with lower wealth would invest in more productive rooms and tools such as facilities for producing agricultural items (like olive oil), stonecutting, and cloth weaving. These houses were more tied to the commercial economy of the city and depended more on purchasing food from the market, rather than being able to match more self-sufficient households. Households that put more time and resources into production of goods therefore did not store perishables and would rely on acquiring them as needed.

Security and Locking Up

By Dr. Allison M. J. Glazebrook

Professor, Greek Social and Cultural History; Genders and Sexualities; Greek Oratory

Brock University

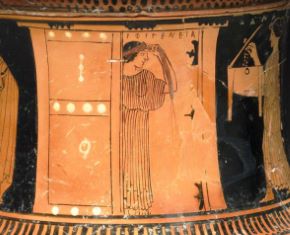

The woman depicted on this vase hesitates to open her place to a late night reveller who bangs the door with his walking staff. She is right to be cautious. The defendant in a court case relates to the jurors how a man named Simon arrived at his house drunk one night and broke down the doors (Lysias 3.6-7). The defendant was not at home but his female kin were. Simon pushed his way in among the women and refused to leave until those accompanying him and some neighbours forced him out. It’s not the only time a speaker in court recounts a home invasion. At another trial, a speaker recounts how his enemies unlawfully entered his home in his absence and began to remove his personal property, including sheep and enslaved workers. They even attacked an elderly freedwoman who attempted to hide some valuable items on her person (Demosthenes 47.52-53). What measures were taken to secure a house and its contents and protect the people within?

While the Greeks did not have electronic security systems, they were very much concerned with security. The textual evidence makes clear that householders locked their doors and kept storage items safe within the house. A play of Aristophanes, for example, mentions the use of a bolt and padlock to secure the main entrance (Aristophanes, Wasps 152-55). Valuable items could be locked in a chest (Demosthenes 25.61; Lysias 12.10) or even buried in a cache beneath the floor of the home (e.g. Houses A v 10, A vi 8, and A 11 at Olynthus). Sleeping quarters seem to have been considered the most secure area of the house and were where wealth and other valuables were kept (Xenophon, Oeconomicus 9.3). Quality of construction would also have been a factor in security. Since houses were commonly of mudbrick, a poorer construction might easily be penetrated by digging through the wall. The wealthier the individual, the greater potential (and likely need) for security.

In this image, a woman opens one of the doors in a set of double doors to a second woman holding a box. Metal bosses visible on the closed door decorate and reinforce the wood. A long keyhole is shown in the top half of the door and a round hoop handle appears attached to the lower half.

A common way to secure a door was with a sliding wooden bolt. The bolt was moved into place by a rope or strap of leather.[1] Keys were long angular metal rods that inserted into a hole in the door to push the bolt back and open the door. Keys have occasionally been found in archaeological excavations. A fine example is a bronze key in the shape of a snake from the Temple of Artemis at Lousoi.

Entrances to houses might require the visitor to pass through a porch and a second set of doors, adding a further level of security (e.g. House A iv 9 at Olynthus). Having a secured location within the home was another way to keep the inhabitants and wealth safe. When men unlawfully invaded a home to seize the property, the enslaved women closed and secured the door to a tower and prevented the men from entering that part of the house. The women were inside the tower at the time of the invasion and so the locking mechanism was on the inside of the door (Demosthenes 47.56).

The owner of a large estate, Ischomachus, recommends housing enslaved members of the household in male and female quarters separated by a locked door (Xenophon, Oeconomicus 9.5). Interestingly, Ischomachus does not suggest the locked door to prevent enslaved workers from self-emancipating, but to prevent stealing and sexual relations without his permission. This example not only shows how much control enslavers had over enslaved workers in their households, but also their mistrust of such workers. Household security, in the Greek mind, focused on insiders as well as outsiders. Only the view of the wealthy landowner survives and so what enslaved people thought about their personal security or what measures they took to protect themselves and any personal goods in these households are not known.

Careful inventory and bookkeeping would have been another way for households to ensure their goods were secure. In Ischomachus’ home, it is the wife who oversees the running of the household, including keeping an inventory of everything that comes in and goes out. It’s her responsibility to make sure all items stay in the right place and to note any discrepancies. She acts as the “guardian” of all items in the house The male head (kurios), given the absence of a police force, is responsible for protecting the household, its members, and its contents from outsiders (Xenophon, Oeconomicus 7.25, 9.14-17). While resorting to violence against an intruder was an option, bringing the offender before a magistrate and prosecuting the offender in a court of law for theft or assault were also possible and socially preferred to escalating a situation.

Home security was very much a concern for the ancient Greeks. In Athens we see that security was both a personal concern and also of interest to the city. Householders took measures to secure their homes and any violation of a household, its members, and its wealth had legal recourse.

Household Production

By John-Michael Bout

What does it mean when you cannot go to the mall? It is hard to imagine life without the ease of amenities and shopping centers. Yet Greeks from the Classical period (5th-4th centuries BCE) thrived in a world like this. There is a common misconception of household production in ancient Greece that visualizes a family creating all their own goods on a small farm and only trading for a few items with locals. This raises a fundamental question about the Greek household (oikos): How self-sufficient was the oikos in reality?

To begin answering this question, it is important to first understand what ‘household production’ even means. The International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences offers this helpful definition: “Household production is the production of goods and services by the members of a household, for their own consumption, using their own capital and their own unpaid labor.” Recent scholarship has debated how self-sufficient the Greek house really was, but before the 1990s, many scholars assumed that every house produced all its own necessary goods and services for survival. This assumption is due to biases and ideals found in the primary sources that survive from Athens. The ancient writer and commander Xenophon wrote in his informative work Oeconomicus 5.1 that an Athenian male citizen’s ideal mode of employment was to be a gentleman farmer. Plato also puts this image forward in his book the Republic 3.370c onwards as the ideal employment for Athenian men. If Xenophon and Plato agree, it must be true. And with that, the debate was closed for many years. This ideal household image, however, was founded on just that, an ideal.

Early debate around ancient household production focused on whether the economy was “primitive” or “modern.” Most thought the economy was clearly primitive. Yet, defining any economy as either “primitive” or “modern” is an unhelpful dichotomy to draw and does not lead to a nuanced, evidence-based conclusion. Moses Finley, in 1973, advocated for a very independent and isolated oikos, and his influence has been pervasive ever since. Finley further argued that lay Greeks only took on economic activities necessary for providing sustenance to themselves and their families, and prioritized farming a plot of land and producing most, if not all, necessary goods themselves. He interpreted Classical Athens as just a large group of net consumers rather than producers and expected most city dwellers to travel outside the walls to open lands to farm. This general approach takes the idealistic philosophies put forward by Xenophon and Plato at face value and ignores the fact that Athenians may have had contradictory attitudes towards their home activities.

Contemporary scholars, such as Bradley Ault, are challenging this approach based on thorough archaeological work being done at Athens and Olynthos. Ault pushes back on a simple view of the oikos and argues that this conclusion comes from a lack of considering texts other than the philosophers and an altogether dismissal of archaeology in the discussion. On top of this, some of the same primary sources that Finley draws from also make mention of citizens busy with work other than farming.

In reality, individual homes had a lot of flexibility to be either self-sufficient with farming and producing their own goods, or more often, to rely heavily on trade in the agora and private shops. They certainly did not have the convenience of modern malls, but that is a far cry from every home being economically independent. Current scholarship interpreting evidence in Athens and Olynthos points towards an interconnected city and a thriving market community. Ault discusses how the evidence of coinage around the agora and the higher housing prices in trade sectors point towards the higher value of the plots of land near market spaces. Further, artifacts and implements have been discovered in and around Athens that originate from all over the Mediterranean, indicating a high level of trade.

Outside this modern debate, it is worth noting that there is very little noticeable difference between buildings where people worked and lived. In most of the references, there is no indication of urban production being done in another space separate from the oikos. While this reality makes archaeological interpretation challenging, it emphasizes the interconnected nature of the simple Greek home to the whole of the city. Ault sums this up nicely when he says, “Clearly the entrepreneurial spirit was alive and well in the Greek polis.”[1]

The last decade has shown a surge in green approaches to energy consumption and general production. One of the byproducts of this societal trend has been a rise in household production. Secondhand thrifting, mending torn clothes, and growing fresh produce are all common ways to live a “green-life.” But how green were the Greeks? While the Greeks’ motivation driving household management and frugality may be different from our societies’ more global goals, it is interesting how many activities are now shared over two thousand years later. In book 7.6-40 of Oeconomicus, Xenophon writes about the dialogue between Socrates and Ischomachus. They discuss how to train men and women alike to be effective in household management and practical tasks. The Greeks cared about consumption and general production through the lens of frugality, whereas the modern trend considers general consumption and production through the lens of global warming and overpopulation. How green were the Greeks? They were green, not from a moral standpoint, but from an economic outlook.

So what kinds of activities were common to a Greek household? Archaeological and literary evidence demonstrates a wide variety of activities such as textile production, animal husbandry, pottery, olive oil pressing, farming, food preparation, stonemasonry, sculpting, cobbling, metalworking, baking, large-scale weaving, and furnace work (shown in the image to the right). As this extensive list demonstrates, the production opportunities in classical Greece were nearly as varied as today. Several of these topics are explored further in chapters 8-10. This list only scratches the surface of the entrepreneurial opportunities available to the Greek household.

In sum, the oikoi of Classical Athens were able to specialize in one form of manufacture or another based on a high level of trade in and out of the city. Instead of Finley’s independent household, the Greeks had a highly interconnected understanding of household production even though the marketplace was not nearly as polished as a modern mall. How self-sufficient was the oikos in reality? There was no need that the oikos be entirely self-sufficient at all.

Diet and Food Production

By Kaylee Janzen

When we think of food preparation in North America today we often think of a kitchen. We might think of a fridge, an oven, or some storage areas. But the ancient Greek “kitchen” looked a bit different. In fact, in many houses there wasn’t a “kitchen” at all. That is to say, many houses did not have a designated room for food preparation. Nevertheless, families did prepare meals in their homes. This chapter aims to look at what the ancient Greeks ate, and how they prepared these things.

The ancient Greek diet included many different foods. They ate vegetables such as beans, garlic, lentils, and radishes. Fish like herring and anchovies were eaten both pickled and fresh. However, meat such as beef, lamb, pork and goat were eaten much less often and were often involved in ritual feasting (e.g. Ath. 1.15). They also had cheese, olives, eggs, honey, apples, figs and dates. But most importantly, bread. Bread was a staple food in the Greek household. In fact, it was used as a utensil and a napkin as well as a food. When eating something that today we might eat with a spoon, like a soup or stew, the ancient Greeks would instead use bread. And in place of napkins they would sometimes have small pieces of bread on which they could wipe their fingers. At the end of the meal it was common to throw these pieces of bread to their dogs.

The first step of making bread is grinding the grain. The most common grain used was barley. This bread was called maza and was simply ground barley mixed with water, then cooked over a fire. There are some mentions of leavened bread by ancient Greek authors but this was a rarity. To grind the grain the ancient Greeks used querns. A quern consists of two stones that the grain is placed in between. The upper stone was tapered at the end to make it easier to grip while the lower stone was often slanted so that the grain would slide down. There was also often a herringbone pattern on the stones to guide the ground grain down the sloped stone. Originally it was thought that mortar and pestles were used as well but now it is more often thought that they were used for grinding things other than grain.

If they were used in the bread making process it was for removing the husks, not grinding the grain. Because of the method of grinding grain, it can sometimes be difficult to tell whether a figure is depicted grinding grain or rolling dough as the two actions can appear quite similar.

For example, this figurine depicts a woman either grinding grain or rolling dough on a table. Both actions depict her making bread, a task commonly represented with such figures. Since the bread making figures depict women doing these actions, we can learn that bread-making was a task for women in the ancient household.

Once the grain was ground up and the dough was rolled, it was time to bake the bread. There were multiple different methods of baking the bread. One of the more common methods was the usage of a dome shaped cover. These covers may or may not have a base for the food. If it was just the cover one would clear a space on the ground, light some coals and cover them with this lid. Once the inside was warmed the coals would be moved to the side and the dough placed inside. The dough could be placed directly on the ground or on a layer of leaves. Then the dome would be closed again and other coals would be heaped up over the cover and the bread was left to bake.

There were other kinds of ovens as well, like this one depicted in this figurine. A fire would simply be lit beneath the oven, but it required someone to keep the fire stoked to maintain a consistent temperature and to turn the contents of the oven and make sure the item cooked evenly. Unlike the bread-making figurines, there are some figures of uncertain gender depicted with ovens. This could indicate that perhaps male members of the household might work around the fire as well.

Some ovens could have the tops removed to become braziers as well. Some braziers had grooves at the side where spits could be placed to roast items. Circular braziers could have bowls placed over them to heat the content in the bowls. There were also grills which could be placed directly over coals or on braziers, used to grill meats and vegetables.

Not every kitchen utensil is immediately recognizable. For example, archaeologists have discovered an artifact shaped like this at various sites.

There have been multiple interpretations as to what it may have been used for. Some thought it was used in metallurgy and attached to bellows, others suggested it carried torches, or maybe it was used as an upside down rhyton (a conical container for liquids) in some sort of ritual. In the end, scholars used a combination of primary literary sources and images on vessels to deduce what this item would have once been used for. A joke found in Aristophanes’ Peace (lines 893-894) about a character’s legs being shaped like this tool provides the item with its name, a lasana (λάσανα) and its use was discovered depicted on a vessel. These items were used to support cooking vessels over a fire and were very useful since they could make any vessel into a cauldron. One could even adjust for the size of the vessel by moving the pieces closer together or further apart.

Of course, there were other utensils used in food production as well. Most of these tools were made of terracotta but there are a few which were bronze. For example, they had bronze cheese graters, which look very similar to the cheese graters we still use in North America today. The ancient Greeks did not use knives at meals but they did have iron cleavers for cutting meat. Archaeologists have even discovered a saucer inscribed with different kitchen utensils. The list includes dishes, platters, little dishes, cups, oil-flasks, half-chous (a little jug), and bowls.

Working from Home

By Jessie Simpson

Many people, due to the Covid-19 Pandemic, have begun to work or do schooling from home, leading us to rethink how spaces are used in our homes. This is both similar and vastly different to homes in the Classical Greek world. It is similar in that working from home was a norm for some sections of society. But how many people today are creating metal helmets, weaving fabric, or carving statues in their homes? This list more closely matches the activities of what is called household industry in ancient Greece. That term includes things going on in homes that were truly industrial. Several home industries of the classical Greeks would be more likely found within a factory today, entirely separated from the home. Other home industries included practices that would have normally been done within the home and yet had become industrialised, like weaving and wool working.

As is discussed elsewhere in this book, some of the everyday chores of the ancients were quite different from ours in North America today. One chore was that of wool working. Women were expected to weave cloth and fashion clothing for the household. They worked on both standing and handheld looms and sometimes owned enslaved people to either do this work for them or help them with this work. The ability to create enough cloth for your entire family was certainly the ideal, but not always the reality for all families of different statuses. People of middling and lower classes, for example, may have had to outsource this work, leading to the industrial side of wool working which could easily take place within the home. Outsourcing is how some of the other chores of the home became industrialised as well. Below, you can see an image taken from an ancient attic oil flask showing the various stages of wool working, with the most well-known, weaving, in the centre. This image shows the number of stages and people that could be involved in the creation of one garment or even just one piece of fabric. The addition of other people and even other looms could lead to more productivity and assist the household industry to thrive. You can see the process of weaving on one of these looms in this linked video.

Quite often, enslaved people were a part of the classical Greek household and their work within the home should not be ignored. Enslaved labour was something that straddled the division between domestic and industrial labour no matter the work they were doing. These individuals were conducting work, in some cases, that would have otherwise just been another domestic task of the women of the household. They could be involved in agriculture as well, a more male dominated sector of a home. It should be noted that these people were a large part of industry within the home whether they were conducting the more domestic work discussed above or the more industrial work that we normally think of that will be discussed below. Slavery in the Greek household will also be discussed in more detail in the chapter on marginalized people.

We can see many industries within the Greek home in the archaeological record. It can be seen by the items associated with a profession taking up the prime spots of sunlight in the courtyard or in adjacent rooms, or just by the sheer amount of these items. Some homes at Olynthus have been found with loom weights in an amount that would signify many more looms than would be necessary for a single household. Sometimes a home with evidence of industry also has later additions to it. Such additions are archaeological evidence of a successful business in that home. Industry can also show up in smaller ways, such as having a small surplus of vegetables from your harvest that could be brought to market. Industries like these would show up extraordinarily little or not at all in the archaeological record.

Taking part in household industry or even just the act of selling surplus could be looked down on quite heavily from the elites in Greece. We can see this in written sources from the period, which are most often written by elite males who had access to better education. An example of this comes from the comic playwright Aristophanes in his play Acharnians, where he insulted the tragic poet Euripides by insinuating that Euripides’ mother was a vegetable-seller. Another character in the play asks Euripides for some of the skandix, likely to be the plant known as wild chervil, which he inherited from his mother. This comment not only accused him of a low status background as the child of a vegetable seller, but also insulted the plays he wrote. Given that this mention was intended as such an insult, we can extrapolate that vegetable sellers were looked down upon in the time of Aristophanes. This insult of Euripides is common in classical comedic plays including Aristophanes’ Thesmophoriazusae (lines 385-390), where Euripides is directly called a “son of the green-stuff woman”. It should be noted that it is debated whether Euripides mother ever truly did sell vegetables.

There is also evidence of the upscaling of agriculture. Some homes at Halieis and Olynthus contained olive crushers, grinding stones, and grape crushing floors. The household could use this equipment to produce a product to disperse. They could also rent it out to others for further profit. The material record includes industrial style tools and even designated rooms with specialized floors, like plaster. An increased number of grindstones, more than could be used by a single household, for example, could indicate that this activity was being industrialized within the home.

It should be noted that in the same way that weaving and agriculture could be scaled up to become an industry within the home, what we normally think of as industrial activities in North America today could be scaled down for the same purpose. While some homes could contain small rooms that could only be entered from the street, these were not always present in homes with more industrial artefacts. This is to say that not all homes would have had workshops to separate the working or industrial areas from the everyday living areas. While these small rooms are an indicator of industry in the home, some industrial activities would take place in the courtyard, or in other rooms inside the house.

What were these industrial activities? Almost anything you could think of as an ancient profession could be brought into the home. There is evidence of shoemaking, marble carving, and even metalworking and glass working within buildings that were also used as homes. The Agora served as a designated marketplace in Athens and was surrounded by people’s homes. As a result, when you were on the outskirts of the Agora, the division between workplace and living space became blurred. There are many homes in this area that have evidence of being a living space and workspace for marble carving. While there were designated industrial buildings for these purposes, for smaller businesses these industrial activities could take place within the home as well.

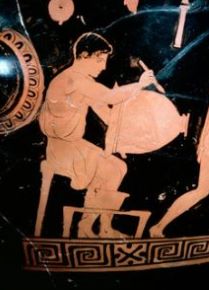

We have several examples of imagery on Athenian pottery that shows one man engaging in industrial work. You can see in the image on this cup (above) that there is a man working on the shaping of a helmet. It doesn’t seem to be taking up too much space and is mobile work that could be done anywhere within the home. We see similar imagery of men carving smaller marble statues and statuettes. To the right, we see an image of a single man painting a vessel, similar to how someone would paint any of the vessels found on this page. This, again, doesn’t take up much space and would be rather portable.

What is visible from these images is that industries we often think of as large had components that could be scaled down and brought into the home. For several industries, we have evidence that they were. A couple of famous houses like this are the House of Mikion and Menon, and the House of Simon the Shoemaker, both found in Athens. There are many other homes like this in Olynthus as well. Industry was a part of many of the homes in ancient Greece, in both large and small ways. It could be as simple as sending your mother to market to sell your extra vegetables!

Water Supply and Waste Management

By Julie Minato

Bathroom spaces throughout history have always been somewhat of a mystery. This is especially true when speaking about the Ancient Greeks, despite the frequent “toilet jokes” in Aristophanes and other comic poets. When Ischomachus shows his new wife around his home in the Oeconomicus, for example, he makes no mention of a bathroom (9.2-5). The only reliable evidence available is the physical remains of what used to be baths and toilets in what would be thought of as the bathroom space and visual evidence of bathing. Only so much information can be gathered from the material evidence alone so the social context of the bathroom space is still unknown.

The best evidence for the ancient Greek bathroom is what remains of bathtubs, toilets, and the drainage systems at ancient sites. It is important to remember that not all of the homes were the same and their bathroom spaces also varied. Some houses at Olynthus, for example, have “bathtubs,” but fragments of stand up basins in others show that washing was commonly done standing up.

Some homes had drains that removed waste and other homes had portable toilets. Some cities, like ones found in Crete, had sewage lines that would lead out of the city where the waste would be disposed of. Other cities did not have such infrastructure and so it was up to the members of the household to dispose of the waste. Homes that were small would likely not have a designated space for the bathroom. To maximize the uses of the space they may not have included a bathroom or if they had a small space, they could have used a portable toilet instead, like a chamber pot, that could be used in any space.

When there was a dedicated space for the bathroom not all bathroom spaces looked the same. At Olynthus, remains of bathtubs and terracotta toilet seats have been found in spaces also used for a variety of other activities. During the Hellenistic period, specialized rooms with multiple seat toilets appeared so more people could use the bathroom at the same time and to maximize the capacity of the space. Most public bathrooms in ancient Greece had multiple seats and no privacy and this would be the same in homes as well even though there would not be as many seats in a home that had a built-in toilet. The design of some toilets had a flushing feature that deposited waste under the floor of the bathroom and water would take the waste out of the house through the sewer system. Smaller homes would typically have a clay pot that would be used for waste and be cleaned out outside of the house. There are different bathroom spaces depending on the location of the house and its size, but it is clear that bathrooms were not a necessary feature of houses and that multiple bathroom spaces in one home was not normal.

Whereas today in North America and other historical periods, like the Antebellum South, bathrooms, whether public or private, can be restricted to particular users, there is no clear evidence that the bathroom space was gendered in ancient Greece or if enslaved people would be prohibited from using the same bathroom space as free individuals. Based on what we know of female virtue, it is likely that women would only be allowed to be with women in the toilet, if the space had more than one seat. The same would go for men.

As discussed above, some toilets had a flushing system that would bring the waste outside of the house and in some cities the waste would be brought outside of the city. Their drains would be cleared manually and after a rainfall. For those families that used clay pots, they would need a supply of water in the home to clean them out.

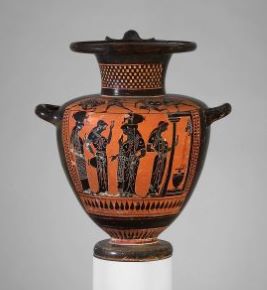

Some homes had their own wells or cisterns and thus their own water source. The type of water supply was different for each home. Some homes included factories (see chapter 10) and thus needed more water than other homes because they needed the water for their work. In other homes the water was used for everyday tasks such as cooking and cleaning and washing. There is evidence at Olynthus of clay pipes that likely brought supplies of water into homes. Water could also come from communal water fountains. It would be collected and stored in hydrias, a special vessel (shown in the image below), for transporting and storing water within the home. There would be multiple hydrias of water that had different uses in the house (washing, drinking, cleaning), but it is unclear how many times each household was allowed to replenish their supply.

What is known is that fetching the water was a woman’s job and more specifically a job for enslaved women in wealthier households. This can be seen in Attic vase paintings, like the scene on the left, which depict groups of women going to the water fountain to collect water. In some cases it is clear that the women depicted are non-Athenian and enslaved, since they have short hair or are decorated with tatoos. From these pottery examples we can see that this was a task for the women which might seem strange when we know that men were usually the ones who did the work outside of the house. Since water in the house was important for everyday life and women would be working in the house most of the time, fetching the water became a task for women.

Although there is not much known about the bathroom space, it still played a vital role in the daily life of the ancient Greeks. Bathrooms are an important part of any home in North America today and over time the Greeks understood this as well and made an effort to separate and distinguish the space from the other rooms of the house. But we have also seen how a designated bathroom space was not necessary. There may not be much known about the social practices of the bathroom space, but from what we know about how the house was set up and the gendering of space we can infer that the bathroom would follow similar practices.

At the Margins

By Shakeel Ahmed

Who are the people at the margins of the Greek household? The imagery around this circular vase captures a moment of an all-male social gathering (the symposium ) in a Greek house. The artist wants us to observe the whole imagery as a continuous action, like a clip of a scene in a movie. But the inclusion of a bulky young man holding a large vessel in his arms arrests the progression of the scene momentarily.

He is seen pouring some liquid (likely wine) from an amphora into a container where the wine would be mixed with water (Greeks saw virtue in drinking diluted wine ). A man and his companion, reclined on a couch, seem oblivious to him and his task. Their disinterest pushes the young man to the margin of this scene. His location at the margin, along with his task and clothing (a short tunic wrapped around the waist), confirm his social status as an enslaved domestic labour. The artist’s choice in depicting him thus seems appropriate when we consider that the Greek household privileged free-born citizens over enslaved individuals.

It is generally thought that the average Athenian household had at least one enslaved labourer. Such persons performed various tasks ranging from childminding and working looms to working alongside their enslaver (of course, not wealthy ones) in agriculture and household industry (see below and chapter 10). Any manual task would be carried out by the enslaved members of the household.

This vase image shows a young man moving heavy furniture, a sympotic couch and a table slung over his shoulders. He is nude, but his build is not particularly athletic. His bent legs and the left foot slightly raised off the ground suggest that he is struggling under the weight of the furniture. His unremarkable physique and un-heroic nudity symbolize his social status as a domestic enslaved labourer.

In the fifth and fourth century BCE, Athenian society was a slave society because many enslaved and formerly enslaved populations influenced its socio-economic landscape. The roles and functions of enslaved people thus contributed to the financial success of the Greek household. In some instances, the enslaver relied on enslaved labour to maximize profits in his trade. Sometimes he worked alongside them and drew the same wage; an Athenian inscription shows that during the construction of the Erechtheum the stonemason Phalarkos worked with his enslaved workers fluting the columns of the east porch (IG13 Erechtheion). Other workers may have lived and worked apart from the enslaver practising a trade or manufacturing products to sell in the market and paying a share of their income to their enslavers (Aesch. 1.97). A law court speech shows that an Athenian purchased a skilled enslaved man, Midas, and his two sons, along with their perfumery business (Hyperides Against Athenogenes 4-27). There is no indication that the enslaver shared his living space with the family of Midas. Perhaps they lived as well as worked at the perfumery. The absence of a mother highlights the tragic incompleteness of the family. Moreover, Midas and his sons change hands from one enslaver to another when they are sold. This case shows that despite having a steady source of income and some independence as enslaved workers” “living apart”, enslaved families lived under the constant fear of separation or drastic change in their living situation (Hyp. Ath. 5).

The fact that enslaved people could earn an income in ancient Greece alerts us to the fact that enslaved individuals could buy their freedom. What was life like for freedmen and women in ancient Greece? Enslaved males likely had an easier time after being freed. Athenian lawcourt cases highlight the vulnerability faced by women in particular who were voluntarily freed by their enslavers or who managed to buy their freedom. We should remember that many enslaved people had to work for a long time to save enough money to buy or be given their freedom. That meant they spent the better part of their lives in slavery. Many never had an opportunity to start a family (Xenophon Oeconomicus 9.5). These people could find themselves isolated outside the enslaver household. The incidental death of a freed and retired nurse at the hands of two Athenian men highlights the risks for freed people living outside of legally recognized households. The old nurse had moved back in with her former enslaver after her husband’s death; having no children, she likely had nowhere else to turn to after serving the household for the greater part of her life. Since she had been released from enslaved status and had no known relatives, Athenian law did not permit her ex-enslaver to prosecute the two men (Demosthenes 47.55-72). In another case, the famous sex labourer, Neaira, drifted from one place to another, trying to establish a household for herself and her children after earning her freedom from a brothel house in Corinth (Demosthenes 59.18-73). In this case, she continued to work in the sex trade until she eventually found stability as the live-in companion of an Athenian man.

Archaeological and textual evidence shows that enslaved labour, besides significantly contributing to the household’s surplus income, also assisted their enslavers (the husband and the wife) in day-to-day activities.

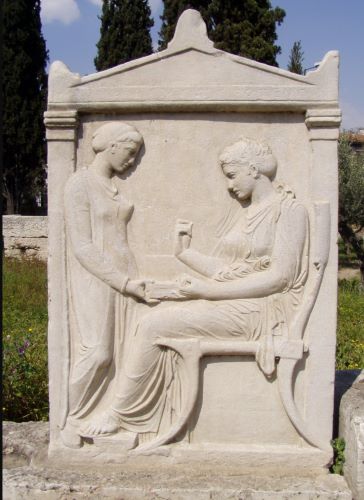

This funerary stele depicts a young, lean, petit woman in a plain long-sleeved chiton helping her enslaver mistress with her jewellery box. The depiction of a comfortably ensconced woman, much larger in size with an elaborate hairstyle and voluminous chiton, highlights the woman’s status as an Athenian wife belonging to a wealthy household. Could an emotional connection have existed between these women despite the disparity in their social status? The inscription on the stele bears one name only, identifying the seated woman as Hegeso. She, and not her connection to the enslaved attendant, is the focus of attention on the tombstone. Her dominant frame contrasts sharply with the slender girl standing at the margin. Greek artists regularly used size and other physical characteristics to distinguish between free and enslaved people. In this case, the unnamed enslaved attendant highlights Hegeso’s social status and wealth, much like the jewellery box, rather than any intimacy between the two women. In addition to their labour, enslaved people served as markers of their enslaver’s wealth and status.

The case concerning the sale of Midas and his family also draws our attention to the sexual exploitation of enslaved people by free citizens. The prosecutor claims that because of his passion for Midas’ youngest son, he agreed to buy the father, his two sons, and their business and not tear apart the whole family. But it also gave him guaranteed sexual access to the young man. Citizens’ involvement with enslaved men and boys did not complicate household affairs, as did citizens’ involvement with enslaved or freedwomen engaged in the city’s entertainment business. Citizens’ relationships with such women could result in children. These women and children threatened Greek households’ wealth and ideological structure, which only granted citizenship to children born to two citizens.

Two sons of a deceased Athenian man, Euctemon, from his relationship with a woman not connected to a recognized Greek household, are at the centre of a property and inheritance dispute in another lawcourt speech (Isaeus, On the Estate of Philoktemon 6.5-28). The prosecutor claims that the sons’ birth mother is Alke, a formerly enslaved sex labourer and a brothel keeper. The speech plays with Athenians’ anxieties over the role of enslaved women in the household and their place in the city as sex labourers. The speaker appeals to the jury to consider the extraordinary stress Alke has caused the legitimate wife of Euctemon’s household. Highlighting her role as a sexual companion, her transgressive mobility in the city, and her habitations at various marginal and less-reputable locales, the speaker paints Alke as a typical companion/ entertainer/ sex labourer who is threatening to break up the legitimate household and rob its legal members of their wealth. The prosecutor strategically stereotypes Alke as an alien woman living beyond the code of decency, looking for the opportunity to fool a citizen of a wealthy household to claim his inheritance and pass off her illegitimate sons as citizens— a significant violation of the laws since only legally recognized Athenian women citizens could bear legitimate children who had a claim to the household. There was no legal prohibition, however, against citizen men’s involvement with alien/enslaved/freed women in the entertainment and sex trade. Wealthy men like Euctemon could afford to set up another house for their mistress (See also [Dem.] 48.53-56 and [Dem.] 59.114). Yet such court speeches also highlight the hardship in the lives of these marginalized women as they try to leave the sex trade and set up a stable household.

Enslaved women also entered the household for all-male gatherings in the andron, from which women-folk were excluded. Enslaved women were invited as hired musicians, dancers, and companions for the male guests’ entertainment. In this vase painting, male guests are entertained by a flute player and a female sexual companion. The inside of the cup also depicts a female dancer. The physical contact between the reclined man and the woman on the right side of the scene shows that entertainment and sex were closely linked in male social gatherings. The presence of an enslaved man at the margin of the scene, leaning against the pillar and quietly observing the proceedings, makes us acutely aware of his low status and his role as server of the guests.

We should remember that all the ancient evidence discussed above preeminently relays the elite male perspective. So, our view of the enslaved experience is limited; at best, it only captures glimpses of reality. Furthermore, the evidence that at first glance shows close ties between enslaved and free might instead demonstrate the emotional labour required of enslaved people in these relationships. Enslaved people needed to obscure their own feelings and desires in the presence of the enslaver in order to be successful in a slave society.

Poverty and Homelessness

By Samantha Fisher

1 in 7 or 4.9 million people in Canada currently live in poverty and according to Statistics Canada more than 235,000 people can experience homeless in any given year, but what do these statistics mean for the ancient Greek world? While poverty and homelessness undoubtedly existed in ancient communities, how do we go about finding these people in the literary and archaeological records when sources are written by the educated male elite and the temporary housing solutions used leave few material traces?