What distinguishes the early modern period is not the emergence of disagreement itself but the stabilization of disagreement through durable communication.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Mass Communication and the Reordering of Political Belief

The early modern period witnessed a profound transformation in the relationship between political authority and belief, driven not simply by new ideas but by new systems for communicating them. Long before the emergence of modern mass media, the spread of printed texts altered how political knowledge circulated, who could access it, and how legitimacy was evaluated. Political belief, once shaped largely through hierarchical transmission via church, court, and custom, increasingly became something that could be encountered independently, debated publicly, and shared across social boundaries. This shift did not occur evenly or peacefully, but it marked a structural change in the conditions under which political authority operated.1

Before the expansion of print, political communication in Europe relied on limited manuscript circulation, oral proclamation, and clerical mediation, all of which reinforced scarcity and control. Access to political information was constrained by literacy, cost, and institutional gatekeeping, ensuring that political belief remained closely tied to established power structures. The introduction of print technology in the fifteenth century did not merely accelerate communication; it altered its scale and social reach, enabling texts to circulate beyond their original institutional contexts and audiences.2 As a result, political ideas could detach from their authors, cross borders, and persist independently of direct oversight, reshaping how individuals encountered and evaluated claims about authority, law, and obligation.

What follows argues that early modern mass communication fundamentally reordered political belief by transforming the mechanisms through which authority was challenged, mobilization occurred, and public opinion emerged. Print culture did not determine political outcomes on its own, nor did it produce uniform effects across regions or populations. Instead, it created new informational environments in which political beliefs could be stabilized, contested, or radicalized at unprecedented scale. By examining the interaction between print, political movements, state responses, and evolving concepts of legitimacy, this study treats mass communication not as a neutral vehicle for ideas but as a formative force in the political transformations of the early modern world.3

Communication before Print: Authority, Scarcity, and Political Knowledge

Before the advent of print, political knowledge in late medieval Europe circulated within systems structured to preserve hierarchy rather than diffusion. Manuscript production was slow, costly, and dependent on trained scribes, which meant that political texts were largely confined to ecclesiastical institutions, royal courts, and urban administrations. This material scarcity shaped political belief by limiting who could encounter written arguments about law, authority, and governance, reinforcing the idea that political knowledge was the domain of elites rather than subjects at large.4

For most of the population, political communication occurred orally through sermons, proclamations, legal rituals, and symbolic performances. These forms were powerful but inherently mediated, relying on clerical or civic officials to interpret and transmit political meaning. Because such communication was episodic and localized, it discouraged sustained political debate and favored affirmation over contestation. Political belief was thus reinforced through repetition and ritual rather than through comparative evaluation of competing claims.5

Manuscript culture did permit the circulation of political critique, but its reach was narrow and socially bounded. Texts questioning ecclesiastical authority or royal prerogative circulated primarily within learned or elite networks, often in Latin, which further restricted access. Even when dissenting ideas were articulated, their fragmentation and limited replication prevented them from coalescing into broad political movements, leaving political belief largely insulated from systematic challenge.6

Control over written records played a central role in maintaining political authority. Access to legal texts, charters, and administrative documents was tightly regulated, ensuring that governance appeared opaque and distant to most subjects. This asymmetry between those who produced political knowledge and those governed by it reinforced the perception that authority derived from tradition, custom, and divine sanction rather than from negotiable human institutions.7 Political belief under these conditions tended to be conservative in form, oriented toward continuity rather than reform.

The limitations of pre-print communication did not prevent political conflict, but they shaped its scale and durability. Popular uprisings and reform efforts were typically local and reactive, lacking the communicative infrastructure needed for sustained coordination across regions. Without durable, replicable texts to stabilize arguments and identities, political belief remained embedded in immediate social contexts rather than abstract principles.8 It was this condition of scarcity and mediation that made the expansion of mass communication in the early modern period so politically destabilizing.

The Printing Press as a Structural Disruption

International Printing Museum, Wikimedia Commons

The introduction of printing in mid-fifteenth-century Europe represented not simply a new tool but a reorganization of how political knowledge was produced and stabilized. By allowing texts to be reproduced mechanically rather than manually, printing altered the relationship between labor, authority, and textual reliability. Political ideas could now circulate with greater consistency across space, reducing the interpretive variability that had characterized manuscript copying and oral transmission.9 This shift mattered politically because it enabled arguments about authority and law to persist beyond local contexts and individual mediators.

Print also transformed the economics of communication. The cost of producing texts declined sharply over time, increasing availability while expanding audiences beyond clerical and administrative elites. Although literacy remained uneven, printed materials could be read aloud, shared, and discussed collectively, allowing political ideas to move indirectly into broader social circulation.10 The press thus created conditions in which political belief could be shaped not only by institutions but by exposure, repetition, and comparison across texts.

Standardization was one of the most politically significant effects of print. Printed laws, proclamations, and polemics fixed language in ways that limited interpretive flexibility, making political claims easier to scrutinize and contest. This standardization did not eliminate disagreement, but it changed its character by anchoring debate to shared textual references rather than mutable oral accounts.11 In this sense, the printing press contributed to a more durable and cumulative form of political discourse.

At the same time, print disrupted existing systems of authority by weakening institutional monopolies over knowledge. Control over scriptoria, archives, and official channels no longer guaranteed control over political communication. Printers operated within commercial networks that did not always align with ecclesiastical or royal priorities,12 enabling texts to circulate beyond intended audiences. Political belief could thus be influenced by actors who were neither officeholders nor traditional elites.

The political consequences of this disruption were not uniform or inevitable. Early printing operated within regulatory environments that varied widely across regions, and authorities quickly recognized the need to license presses and monitor output. Nevertheless, the very effort to regulate print acknowledged its capacity to shape belief at scale. Attempts at censorship often confirmed, rather than neutralized, the press’s role as a force capable of destabilizing established political narratives.13

Crucially, the printing press altered the temporal dimension of political belief. Texts could now endure, be reprinted, and resurface across decades, allowing political ideas to outlive the circumstances of their initial production. This persistence enabled the accumulation of political arguments over time, laying the groundwork for ideological traditions rather than isolated episodes of dissent.14 The press did not create political conflict, but it fundamentally reshaped the conditions under which political belief could form, spread, and endure.

Challenging Religious and Monarchical Authority

The expansion of print created new conditions under which religious and monarchical authority could be questioned without requiring direct access to power. Previously, challenges to church or crown depended on proximity to institutions or elite patronage. Print altered that dynamic by allowing critiques to circulate independently of their authors, weakening the personal and institutional barriers that had long constrained dissent. Authority was no longer encountered solely through embodied representatives such as priests, magistrates, or royal officials, but increasingly through texts that could be read, copied, and discussed beyond the reach of their original contexts.15

Religious authority proved especially vulnerable to this transformation because it rested on interpretive control over doctrine and scripture. Once theological arguments could be disseminated widely in vernacular languages, competing interpretations became difficult to contain. Disputes that might once have remained confined to clerical circles instead entered broader public consciousness, where they intersected with grievances about taxation, jurisdiction, and local autonomy.16 Religious belief thus became entangled with political loyalty, as challenges to ecclesiastical authority often implied limits on monarchical power as well.

Monarchical authority faced a related, though distinct, challenge. Printed critiques of royal policy, legal prerogative, and governance practices introduced new ways of evaluating rulers that did not rely exclusively on tradition or divine sanction. Subjects could encounter arguments that framed kingship as conditional, accountable, or bounded by law, even if such ideas remained controversial or dangerous.17 The existence of these arguments in durable textual form made them harder to suppress and easier to revive, contributing to a gradual shift in how political obedience was conceptualized.

Print also facilitated the coordination of opposition by allowing disparate grievances to be framed within shared interpretive narratives. Texts could link religious reform, legal reform, and resistance to arbitrary authority into coherent critiques that transcended local conditions. This did not require mass literacy to be effective; ideas circulated through reading aloud, paraphrase, and communal discussion.18 As a result, political belief increasingly reflected exposure to abstract arguments rather than solely lived experience or inherited custom.

The challenge posed by print to religious and monarchical authority did not lie in any single text or movement, but in the cumulative effect of sustained communication outside institutional control. Authority was no longer reinforced only through ritual affirmation and legal command but had to contend with competing explanations of legitimacy. Over time, this altered the political imagination of early modern societies, making dissent conceivable as a reasoned position rather than a purely transgressive act.19

Print and the Formation of Political Movements

Print transformed political action by enabling ideas to move beyond isolated acts of dissent and into sustained movements with recognizable goals and shared identities. Prior to mass communication, political unrest often emerged in response to immediate local conditions and dissipated once those pressures eased. Print altered this pattern by allowing grievances to be framed within broader interpretive narratives that could circulate across regions. Political belief thus became less reactive and more programmatic, shaped by exposure to arguments that linked individual experiences to collective causes.20

Printed materials also facilitated continuity in political organizing. Pamphlets, petitions, and manifestos could be reproduced, preserved, and reissued, allowing movements to maintain coherence over time even when direct coordination was difficult. This durability mattered politically because it enabled ideas to accumulate rather than disappear with the resolution of a single crisis. Movements could draw on earlier texts to legitimize present action, creating a sense of historical continuity that strengthened commitment and solidarity among participants.21

The formation of political movements through print did not depend on universal literacy. Texts were frequently read aloud, summarized, or adapted for oral transmission, allowing printed arguments to reach audiences well beyond those who could read independently. In this way, print functioned as a catalyst rather than a replacement for existing communicative practices.22 Political belief circulated through a hybrid environment in which written texts informed oral discussion, embedding abstract principles within everyday social interaction.

Print also reshaped leadership within political movements. Authority increasingly derived from the ability to articulate persuasive arguments rather than from social status alone. Individuals who could write effectively, marshal evidence, or frame grievances compellingly gained influence even without formal office. This shift did not eliminate hierarchy, but it diversified the sources of political authority, making movements less dependent on traditional elites and more responsive to ideological coherence.23

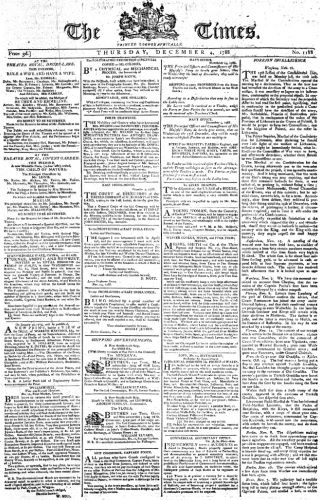

The Emergence of Public Opinion as a Political Force

The expansion of print culture contributed to the emergence of public opinion as a distinct political force by creating shared spaces of discussion beyond formal institutions of power. Political belief increasingly took shape not only through private conviction or local allegiance but through participation in collective discourse. Newspapers, pamphlets, and periodicals fostered environments in which political arguments could be encountered repeatedly, compared across sources, and debated among peers, a development that altered the conditions under which political legitimacy was evaluated.24 This shift marked a departure from earlier political cultures in which belief was largely shaped by deference to authority rather than engagement with competing claims.

Social spaces associated with print played a crucial role in this transformation. Coffeehouses, salons, and reading societies functioned as informal arenas where political information circulated and opinions were formed through conversation, often linking print consumption to collective interpretation.25 These spaces did not operate independently of social hierarchy, but they enabled a broader range of participants to engage with political ideas than had previously been possible. Public opinion emerged not as a unified voice but as a dynamic process through which political beliefs were articulated, contested, and refined through interaction.

The growing visibility of public opinion altered the behavior of political authorities. Rulers and institutions increasingly recognized that legitimacy depended not only on law, tradition, or coercion but on perception, especially as political debate became more publicly accessible through print. Efforts to shape public opinion through official publications, controlled news, and symbolic communication reflected an awareness that political belief could no longer be assumed.26 Even when governments sought to suppress dissenting views, the very act of suppression acknowledged the influence of public discourse as a factor in political stability.

Public opinion did not replace other sources of political authority, nor did it function uniformly across societies. Its influence varied according to literacy rates, censorship regimes, and social structures, limiting its reach in some contexts while amplifying it in others. Nevertheless, the emergence of public opinion introduced a new dimension to political life: belief became something that could be mobilized, measured, and feared.27 This development reshaped the relationship between rulers and subjects, laying the groundwork for later democratic and revolutionary movements without presuming their inevitability.

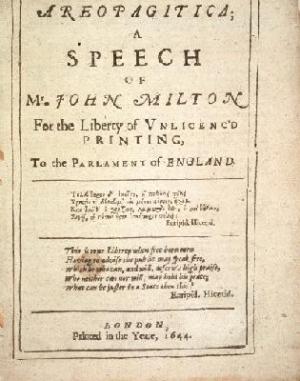

Propaganda, Censorship, and the State Response

As mass communication expanded in the early modern period, political authorities were forced to confront a communicative environment they no longer fully controlled. The same print networks that enabled dissent also created opportunities for rulers to shape political belief proactively. States increasingly recognized that governing required not only enforcing laws but managing information, treating communication as a domain of power rather than a neutral conduit.28 Propaganda emerged not as a modern invention but as a pragmatic response to the growing visibility and volatility of public discourse.

Censorship was one of the earliest and most direct tools employed to regulate print. Licensing systems, prepublication approval, and restrictions on printers sought to limit the circulation of politically or religiously destabilizing texts, reflecting anxieties about the social reach of print.29 These measures revealed an understanding that unchecked communication could undermine authority by normalizing dissent or exposing contradictions within official narratives. Yet censorship was rarely comprehensive, and its uneven enforcement often revealed the limits of state capacity rather than its strength.

Alongside repression, states adopted strategies of persuasion. Official proclamations, authorized histories, and sanctioned religious texts were printed to reinforce legitimacy and frame political events in favorable terms. Print allowed rulers to present themselves as guardians of order, faith, and justice, appealing to reasoned belief rather than relying solely on coercion.30 This shift signaled a growing awareness that political obedience depended on narrative coherence as much as institutional power.

The tension between censorship and propaganda exposed a fundamental contradiction in early modern governance. Efforts to suppress unauthorized texts frequently increased their appeal, lending them an aura of forbidden knowledge, while simultaneously drawing attention to the very ideas authorities sought to contain.31 At the same time, official messaging risked appearing defensive or manipulative, particularly when it conflicted with lived experience. Political belief thus evolved in an environment shaped as much by skepticism toward authority as by acceptance of it.

State responses to print varied widely across regions and regimes. Some governments tolerated limited debate while drawing firm boundaries around core institutions, whereas others pursued aggressive suppression of dissent. These differences reflected broader political cultures and administrative capacities rather than consistent ideological commitments, illustrating that control over communication depended as much on state infrastructure as on intent.32 What united these regimes was a shared recognition that communication had become a domain of governance in its own right.

The interaction between propaganda and censorship revealed the extent to which mass communication had altered political power. Authority could no longer be sustained through silence or ritual alone; it had to engage with an informed and increasingly critical public. Even where states succeeded in controlling print, they did so by acknowledging its political significance.33 The early modern struggle over communication thus marked a turning point in the relationship between belief and rule, one whose consequences extended well beyond the period itself.

Political Theory in Print: From Elite Philosophy to Popular Ideology

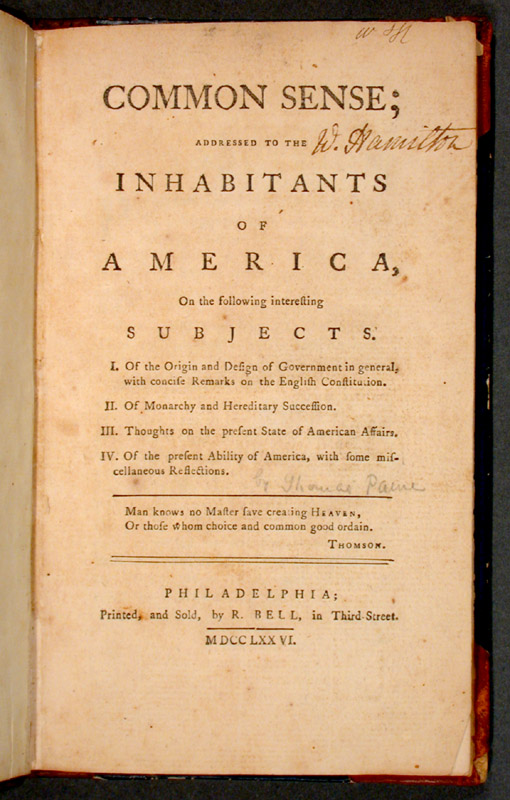

The expansion of print transformed political theory from a largely elite discourse into a body of ideas that could circulate beyond universities, courts, and clerical institutions. Before the early modern period, political theory was typically embedded in specialized languages and genres that limited its audience. Print disrupted this exclusivity by allowing arguments about sovereignty, law, and governance to be reproduced and encountered outside their original intellectual settings, altering how political reasoning entered public life.34 As a result, political theory increasingly functioned not only as scholarly reflection but as a resource for public reasoning.

Printed political theory did not reach broader audiences unchanged. Texts were often condensed, adapted, or reframed to address contemporary concerns, blurring the boundary between abstract philosophy and practical argument. Ideas about authority, consent, and obligation entered public discourse through pamphlets, commentaries, and polemics that emphasized application over systematic coherence.35 Political belief was shaped less by comprehensive theoretical systems than by exposure to selected concepts that could be mobilized in specific contexts.

This process altered the relationship between political theory and political action. Concepts that had once circulated primarily among educated elites began to inform debates over taxation, religious conformity, and legal rights. Print allowed political arguments to be detached from their original intellectual frameworks and reembedded in local struggles, giving them new meanings and functions.36 Theory thus became a tool of persuasion as much as a mode of explanation, influencing how political claims were articulated and justified.

The popularization of political theory also introduced new tensions. Simplified or selective interpretations could distort complex arguments, producing ideological rigidity or misunderstanding. At the same time, broader circulation made political ideas more vulnerable to contestation, as competing interpretations confronted one another in print.37 Political belief increasingly emerged from this contested terrain, shaped by debate rather than deference to authoritative interpretation.

By the late early modern period, political theory had become an integral component of political culture rather than a peripheral scholarly pursuit. Print enabled ideas to accumulate, interact, and persist across generations, contributing to the formation of ideological traditions that extended beyond immediate political crises. This transformation did not eliminate hierarchy or conflict, but it redefined the role of theory in political life, ensuring that abstract concepts could inform belief and action at a societal scale.38

Vernacular Print, Identity, and Proto-Nationalism

The spread of vernacular print reshaped political identity by expanding the audiences who could engage directly with political texts. As printing moved beyond Latin into local languages, political arguments became accessible to readers previously excluded from elite discourse. This linguistic shift did more than increase comprehension; it altered how individuals understood their relationship to authority by framing political issues in familiar cultural terms. Political belief increasingly developed within shared linguistic communities rather than through distant institutional voices.39

Vernacular print also encouraged the formation of collective identities grounded in language and custom. Readers encountering the same texts in their own language could imagine themselves as part of a broader community with shared concerns and interests. Political arguments circulated not simply as abstract ideas but as expressions of common experience, reinforcing bonds among readers who might never meet in person.40 This process contributed to the emergence of proto-national consciousness without presupposing modern nationalism.

The political implications of vernacular print were especially visible in contexts of religious reform and resistance to centralized authority. Texts written in local languages could mobilize populations around grievances framed as threats to customary rights or communal autonomy. By linking political belief to language, print helped naturalize the idea that political authority should reflect the values and traditions of particular communities rather than universal or imposed standards.41

At the same time, vernacularization introduced new tensions within political life. Linguistic fragmentation could hinder coordination across regions and reinforce localism, even as it strengthened internal cohesion. Political belief thus developed unevenly, shaped by competing identities and overlapping loyalties. Vernacular print did not produce unified political cultures, but it transformed the basis on which political belonging was imagined, setting the stage for later national movements while remaining firmly rooted in early modern conditions.42

Global Dimensions of Early Modern Mass Communication

Although the development of print is often examined within a European framework, early modern mass communication unfolded within a broader global context shaped by empire, trade, and cross-cultural exchange. Printed texts traveled alongside merchants, missionaries, and administrators, embedding political ideas within networks that extended far beyond their points of origin. Mass communication thus operated not only as a domestic force but as an instrument through which political beliefs were transmitted, adapted, and contested across imperial boundaries.43

Colonial administrations relied heavily on print to assert authority over distant territories. Laws, proclamations, catechisms, and instructional manuals were produced to standardize governance and impose institutional norms in unfamiliar settings. Print offered a means of projecting political order across space, allowing metropolitan authorities to articulate expectations and obligations without continuous physical presence.44 Political belief in colonial contexts was therefore shaped by encounters with texts that represented distant power while attempting to localize its legitimacy.

Missionary activity further expanded the global reach of print. Religious texts translated into local languages carried not only theological messages but implicit political assumptions about hierarchy, obedience, and social organization. These texts interacted with existing belief systems in complex ways, sometimes reinforcing colonial authority and at other times providing resources for reinterpretation or resistance.45 Mass communication thus functioned as a site of negotiation rather than simple transmission, producing hybrid political beliefs that reflected both imposed and indigenous frameworks.

Global circulation also exposed the limits of print’s influence. Literacy barriers, oral traditions, and selective adoption constrained the reach of written communication in many regions. Political belief continued to be shaped by local customs, social structures, and material conditions that print could not fully override.46 In some cases, printed texts acquired authority precisely because they were mediated through oral explanation, embedding foreign ideas within familiar interpretive practices rather than displacing them.

The global dimensions of early modern mass communication complicate any linear narrative of political transformation. Print did not produce uniform outcomes across societies, nor did it operate independently of power relations. Instead, it became one of several forces shaping political belief within a world increasingly defined by connection and asymmetry. By tracing the movement of texts across cultural and imperial boundaries, the early modern period reveals mass communication as both an agent of integration and a catalyst for political diversity rather than convergence.47

Limits of Print Power and Uneven Political Transformation

Despite its transformative effects, print did not reshape political belief uniformly or universally. Access to printed materials remained constrained by literacy, cost, geography, and social hierarchy, shaping who could encounter political arguments directly. Rural populations, women, and the poor often encountered political ideas indirectly or not at all, limiting the reach of print-driven change.48 Political belief in many contexts continued to be shaped primarily by local authority, custom, and personal experience rather than sustained engagement with printed argument.

Even where printed texts circulated widely, their influence depended on existing social and institutional structures. Print could amplify ideas, but it could not guarantee acceptance or understanding. Readers interpreted texts through the lenses of prior belief, religious tradition, and communal identity, producing divergent responses to the same material.49 As a result, print often intensified disagreement rather than producing consensus, reinforcing fragmentation within political cultures rather than coherence.

Oral communication and performance remained central to political life throughout the early modern period. Sermons, public rituals, rumor, and informal discussion frequently mediated the meaning of printed texts, reshaping their content in the process. Rather than replacing oral culture, print interacted with it, creating layered systems of communication in which written arguments gained authority only when integrated into familiar modes of exchange.50 Political belief thus emerged from a dynamic interplay between print and older communicative forms.

These limitations underscore the importance of avoiding technological determinism in assessing the political impact of mass communication. Print did not compel political transformation on its own, nor did it operate independently of power relations and social conditions. Its influence was contingent, uneven, and often contested.51 Recognizing these limits allows for a more precise understanding of how early modern political belief evolved, shaped by communication technologies without being reducible to them.

Conclusion: Mass Communication and the Modern Political Imagination

The early modern expansion of mass communication reshaped political belief by transforming the conditions under which authority, legitimacy, and dissent were understood. Print did not simply accelerate the circulation of ideas already in motion; it altered how political meaning was produced, stabilized, and contested. By enabling texts to persist beyond local contexts and individual mediators, mass communication reconfigured the relationship between belief and power, making political authority increasingly subject to scrutiny, interpretation, and debate.52

This transformation unfolded unevenly and without inevitability. Print empowered new forms of political engagement while leaving existing hierarchies largely intact. It enabled collective movements without guaranteeing coherence, and it fostered public opinion without dissolving deference or coercion. Political belief in the early modern period emerged from a complex interaction between communication technologies, social structures, and institutional responses, resisting reduction to any single causal narrative.53

What distinguishes the early modern period is not the emergence of disagreement itself but the stabilization of disagreement through durable communication. Political ideas could now accumulate, circulate, and reappear across generations, allowing belief to become historical rather than episodic. This persistence laid the groundwork for ideological traditions that extended beyond immediate crises, shaping how communities understood authority and their own role within political life.54

By tracing the effects of mass communication across religious reform, political movements, state responses, and global exchange, this essay has emphasized communication as a structuring force rather than a neutral medium. Early modern societies did not simply adopt new technologies; they adapted to new informational realities that reshaped political imagination itself. In doing so, they set the conditions for modern politics, in which belief, persuasion, and legitimacy remain inseparable from the systems through which ideas circulate.55

Appendix

Footnotes

- Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 3–42.

- Adrian Johns, The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 30–67.

- Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), 14–26.

- M. T. Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Blackwell, 2013), 146–182.

- Susan Reynolds, Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 215–248.

- Brian Tierney, The Crisis of Church and State, 1050–1300 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988), 97–131.

- Richard Southern, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages (London: Penguin, 1990), 102–129.

- Steven Justice, Writing and Rebellion: England in 1381 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 201–236.

- Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, 59–88.

- Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450–1800 (London: Verso, 1997), 248–276.

- Johns, The Nature of the Book, 120–156.

- Andrew Pettegree, The Book in the Renaissance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 67–101.

- Robert Darnton, The Forbidden Best-Sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France (New York: Norton, 1995), 11–38.

- Anthony Grafton, The Footnote: A Curious History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 29–54.

- Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, 303–330.

- Peter Marshall, Religious Identities in Henry VIII’s England (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), 1–24.

- Quentin Skinner, The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), 239–264.

- Andrew Pettegree, Brand Luther: 1517, Printing, and the Making of the Reformation (New York: Penguin Press, 2015), 87–112.

- Mark Knights, Representation and Misrepresentation in Later Stuart Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 14–37.

- Charles Tilly, Popular Contention in Great Britain, 1758–1834 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 32–58.

- Mark Knights, Politics and Opinion in Crisis, 1678–81 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 89–118.

- David Zaret, Origins of Democratic Culture: Printing, Petitions, and the Public Sphere in Early-Modern England (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 54–83.

- Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, 51–56.

- Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, 35–56.

- Brian Cowan, The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 92–121.

- Knights, Representation and Misrepresentation in Later Stuart Britain, 61–89.

- Zaret, Origins of Democratic Culture, 129–158.

- Peter Burke, A Social History of Knowledge: From Gutenberg to Diderot (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000), 91–118.

- Annabel Patterson, Censorship and Interpretation: The Conditions of Writing and Reading in Early Modern England (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), 15–43.

- Jason Peacey, Politicians and Pamphleteers: Propaganda During the English Civil Wars and Interregnum (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), 1–29.

- Robert Darnton, The Literary Underground of the Old Regime (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982), 3–27.

- Mark Goldie, “The English System of Liberty,” in The Cambridge History of Political Thought 1450–1700, ed. J. H. Burns and Mark Goldie (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 40–78.

- Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, 57–73.

- Skinner, The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, vol. 1, 9–35.

- J. G. A. Pocock, Politics, Language and Time (New York: Atheneum, 1971), 3–41.

- Zaret, Origins of Democratic Culture, 201–228.

- Jonathan Scott, England’s Troubles: Seventeenth-Century English Political Instability in European Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 112–139.

- Mark Goldie, “The Civil Religion of James Harrington,” in The Languages of Political Theory in Early-Modern Europe, ed. Anthony Pagden (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 197–222.

- Peter Burke, Languages and Communities in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 45–72.

- Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983), 37–46.

- Alexandra Walsham, Charitable Hatred: Tolerance and Intolerance in England, 1500–1700 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006), 112–138.

- Anthony D. Smith, The Ethnic Origins of Nations (Oxford: Blackwell, 1986), 134–160.

- Anthony Grafton, Worlds Made by Words: Scholarship and Community in the Modern West (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 155–182.

- Lauren Benton, A Search for Sovereignty: Law and Geography in European Empires, 1400–1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 104–132.

- Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Connected Histories: Notes towards a Reconfiguration of Early Modern Eurasia (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997), 20–46.

- Rosalind O’Hanlon, “Performance in a World of Paper: Puranic Histories and Social Communication in Early Modern India,” Past & Present 219 (2013): 87–126.

- Burke, A Social History of Knowledge, 189–213.

- David Vincent, Literacy and Popular Culture: England 1750–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 1–27.

- Roger Chartier, The Cultural Uses of Print in Early Modern France (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 3–32.

- Alexandra Walsham, “Oral Culture and Print Culture in Early Modern England,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Protestant Reformations, ed. Ulinka Rublack (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 339–357.

- Peter Burke, Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe, 3rd ed. (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009), 281–302.

- Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, 703–729.

- Roger Chartier, The Cultural Uses of Print in Early Modern France (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 121–145.

- Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, 161–175.

- Burke, A Social History of Knowledge, 215–240.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 1983.

- Benton, Lauren. A Search for Sovereignty: Law and Geography in European Empires, 1400–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Burke, Peter. A Social History of Knowledge: From Gutenberg to Diderot. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000.

- —-. Languages and Communities in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- —-. Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe. 3rd ed. Farnham: Ashgate, 2009.

- Chartier, Roger. The Cultural Uses of Print in Early Modern France. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

- Clanchy, M. T. From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 2013.

- Cowan, Brian. The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

- Darnton, Robert. The Forbidden Best-Sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France. New York: Norton, 1995.

- —-. The Literary Underground of the Old Regime. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982.

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- Febvre, Lucien, and Henri-Jean Martin. The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450–1800. London: Verso, 1997.

- Goldie, Mark. “The Civil Religion of James Harrington.” In The Languages of Political Theory in Early-Modern Europe, edited by Anthony Pagden, 197–222. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- —-. “The English System of Liberty.” In The Cambridge History of Political Thought 1450–1700, edited by J. H. Burns and Mark Goldie, 40–78. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Grafton, Anthony. The Footnote: A Curious History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- —-. Worlds Made by Words: Scholarship and Community in the Modern West. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Habermas, Jürgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989.

- Johns, Adrian. The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Justice, Steven. Writing and Rebellion: England in 1381. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

- Knights, Mark. Politics and Opinion in Crisis, 1678–81. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- —-. Representation and Misrepresentation in Later Stuart Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Marshall, Peter. Religious Identities in Henry VIII’s England. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006.

- O’Hanlon, Rosalind. “Performance in a World of Paper: Puranic Histories and Social Communication in Early Modern India.” Past & Present 219 (2013): 87–126.

- Patterson, Annabel. Censorship and Interpretation: The Conditions of Writing and Reading in Early Modern England. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

- Peacey, Jason. Politicians and Pamphleteers: Propaganda During the English Civil Wars and Interregnum. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

- Pettegree, Andrew. The Book in the Renaissance. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

- —-. Brand Luther: 1517, Printing, and the Making of the Reformation. New York: Penguin Press, 2015.

- Pocock, J. G. A. Politics, Language and Time. New York: Atheneum, 1971.

- Reynolds, Susan. Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Scott, Jonathan. England’s Troubles: Seventeenth-Century English Political Instability in European Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Skinner, Quentin. The Foundations of Modern Political Thought. Vols. 1–2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

- Smith, Anthony D. The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Oxford: Blackwell, 1986.

- Southern, Richard. Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages. London: Penguin, 1990.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. Connected Histories: Notes towards a Reconfiguration of Early Modern Eurasia. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Tierney, Brian. The Crisis of Church and State, 1050–1300. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988.

- Tilly, Charles. Popular Contention in Great Britain, 1758–1834. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Vincent, David. Literacy and Popular Culture: England 1750–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Walsham, Alexandra. Charitable Hatred: Tolerance and Intolerance in England, 1500–1700. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006.

- —-. “Oral Culture and Print Culture in Early Modern England.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Protestant Reformations, edited by Ulinka Rublack, 339–357. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Zaret, David. Origins of Democratic Culture: Printing, Petitions, and the Public Sphere in Early-Modern England. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.