Whenever religion merges with nationalism, Hypatia’s shadow reappears. Her story warns that the moment belief wields the sword, it ceases to be faith and becomes ideology.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Philosopher and the Crossroads of Empire

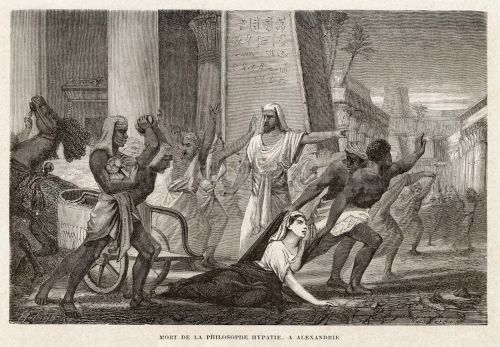

In the early fifth century, Alexandria stood as one of the most vibrant intellectual centers of the late Roman world. Its marble colonnades and crowded harbors bore witness to a city where Greek philosophy, Egyptian mysticism, and Christian theology intertwined within a single civic body. Yet that same mixture of learning and faith made it combustible. The year 415 CE would prove decisive. In that spring, Hypatia (mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher) was seized by a Christian mob, stripped, flayed, and killed. Her death, preserved in grim detail by the church historian Socrates Scholasticus, marked more than the end of an individual life. It symbolized a turning point in the moral and political trajectory of the Roman Empire, as the intellectual tolerance of classical culture gave way to the militant orthodoxy of a new religious state.1

The figure of Hypatia has long served as both historical person and cultural allegory. Trained in Neoplatonism, she succeeded her father Theon as head of the Alexandrian school, where she taught mathematics and philosophy to a diverse circle of students that included pagans, Christians, and imperial officials.2 Her presence in civic life was extraordinary for a woman of her time, and her reputation for virtue and learning placed her among the city’s elite. When political rivalry erupted between the prefect Orestes and the Patriarch Cyril, Hypatia’s role as mediator became fatal. Accused by Cyril’s supporters of using sorcery to influence Orestes, she was transformed in the public imagination from philosopher to pagan witch, a blasphemer whose intellect had to be purged from the Christian city.3

Her murder did not occur in isolation but within the wider evolution of Christianity from persecuted minority to imperial faith. The conversion of Emperor Constantine in the fourth century, followed by Theodosius I’s decrees outlawing pagan worship, fundamentally altered the empire’s religious landscape. By the time of Hypatia’s death, Christianity no longer merely sought survival; it wielded the instruments of state power.4 The laws of the Theodosian Code, the closure of temples, and the destruction of the Serapeum two decades earlier had already foreshadowed the violence that would engulf Alexandria’s last philosopher. The city that once hosted the Museum and Library had become a theater where faith defined legitimacy and dissent equaled treason.

To study Hypatia’s death is therefore to examine the moral transformation of power itself. Her life stood at the intersection of knowledge and dogma, her end at the moment when the empire’s intellectual pluralism was sacrificed to theological certainty. In this crucible of politics, philosophy, and religion, the roots of Christian nationalism, faith fused with authority, first took recognizable form. The philosopher’s blood in Alexandria was the ink that would write a new chapter in Western history, one in which the Church no longer suffered persecution but learned to wield it.

The City of Knowledge and Division

In late antiquity, Alexandria was a paradox of brilliance and fragility. Founded by Alexander the Great and once home to the greatest library of the ancient world, it embodied the intellectual ambition of Hellenism while remaining a cauldron of social tension. Greeks, Egyptians, Jews, and an increasingly dominant Christian community all claimed the city as their own. Its streets were crowded not only with traders and scholars but also with rival processions of monks, philosophers, and civic partisans. The political institutions of the city (its council, its prefect, and its bishopric) were inseparable from its theological divisions. As Christopher Haas observes, Alexandria’s geography itself mirrored its conflict: sacred enclosures, synagogues, and churches divided neighborhoods along ideological lines, each faction policing its own moral boundaries.5

By the end of the fourth century, these boundaries had hardened into open violence. The destruction of the Serapeum in 391 CE, ordered by imperial decree and carried out under Bishop Theophilus, became a defining event in the city’s collective memory.6 The temple of Serapis, once a symbol of Alexandrian synthesis, melding Greek and Egyptian devotion, was reduced to rubble by Christian zealots who regarded its rituals as abominations. Pagan philosophers fled or were forced into silence. The state’s decision to back the bishop over the temple marked a profound shift in authority: imperial power was no longer neutral in the contest of beliefs but an instrument of religious orthodoxy.7

When Cyril succeeded his uncle Theophilus as patriarch in 412 CE, the city’s balance of power tilted further. His election was contested, and riots between rival factions left hundreds dead. The imperial prefect Orestes, representing civil administration, resisted ecclesiastical interference, defending the autonomy of the state against clerical domination. Hypatia, admired by both men, became their intermediary, a philosopher attempting to preserve reason amid fanaticism.8 Yet her influence over Orestes made her a target. To Cyril’s supporters, she was not a mediator but an obstacle to divine order, an emblem of the pagan world’s persistence in a Christian empire.

The antagonism between Cyril and Orestes was more than a personal feud; it exposed the constitutional crisis of late antiquity. Was the empire to be governed by imperial law or by sacred authority? The parabalani, the militant brotherhood nominally responsible for caring for the sick, served as the patriarch’s private militia, often attacking those who opposed the bishop’s will.9 Alexandria thus became a miniature reflection of the empire’s transformation, where Christian leaders could command violence under the guise of faith, and civic order bowed before religious conviction.

Within this climate, Hypatia’s philosophical school stood as the last enclave of Hellenic rationalism in the city. Her students, among them Synesius of Cyrene, later a Christian bishop, illustrate the porous boundaries that still existed between faith and philosophy.10 Yet even such coexistence was precarious. The philosopher’s adherence to Platonic inquiry, her public teaching, and her friendship with the prefect were all read through a theological lens by those who saw civic neutrality as betrayal. The city of knowledge had become, by the early fifth century, a city divided by the very forces that had once made it great.

The Accusation of Magic and the Politics of Purity

Accusations of sorcery were neither new nor random in late antiquity. They emerged at the intersection of theology, gender, and power. By the early fifth century, the rhetoric of “magic” had become a political weapon wielded against intellectuals who threatened the moral monopoly of the Church. In Alexandria, this charge was aimed squarely at Hypatia. To her detractors, the instruments of mathematical calculation (the astrolabe, the hydrometer, the geometric compass) were not tools of reason but tokens of occult influence. Her science, rooted in Platonic cosmology, was reframed as witchcraft, her philosophy as impiety.¹¹

This conflation was not accidental. The early Christian imagination was saturated with fear of the magician, a figure who defied divine order through secret knowledge. Sermons and hagiographies of the period often juxtaposed saint and sorcerer: one purified by faith, the other corrupted by intellect.12 The patriarch Cyril and his followers capitalized on this imagery, spreading rumors that Hypatia used spells to obstruct reconciliation between Orestes and the bishop.13 In a culture where purity was the boundary between salvation and damnation, such an accusation was tantamount to a death sentence.

Hypatia’s gender amplified the scandal. In an empire increasingly shaped by ascetic ideals, the sight of a woman instructing men in philosophy was itself a challenge to clerical norms. The Church Fathers had long identified female independence with spiritual danger, from Eve’s curiosity to the Sibyl’s ambiguous prophecy. To male clerics, a learned woman was either a virgin saint or a witch; there was little room between.14 Hypatia’s public authority therefore violated not only theology but the patriarchal structure that underpinned it.

The rhetoric of purity that justified her persecution reflected a deeper anxiety within Christian society: the fear that remnants of pagan thought might corrupt the body of believers. The Theodosian Code, promulgated in 438 but reflecting earlier edicts, criminalized divination, sacrifices, and “impious rites,” equating philosophical practices with demonic worship.15 Magic, in this legal sense, became the language of exclusion, a way to define Christian identity by condemning what it was not. In Alexandria, this translated into a civic theology in which intellectual independence equaled moral deviance.

Yet to label Hypatia’s murder purely as a religious act would be to ignore the political opportunism behind it. The accusation of sorcery served a strategic function: it converted a philosophical opponent into a heretic and transformed political assassination into moral purification.16 The same mechanism that condemned Hypatia would later animate inquisitions, witch hunts, and confessional wars across Europe, a template born in the streets of a divided city.

Murder and Martyrdom: The Death of Hypatia

The events of March 415 CE unfolded with chilling precision. As tensions between the prefect Orestes and the patriarch Cyril reached their peak, Alexandria’s streets once again became a stage for public violence. According to the church historian Socrates Scholasticus, Hypatia was seized by a mob of parabalani, members of a militant brotherhood nominally charged with tending to the sick but long associated with violent enforcement of ecclesiastical power.17 They dragged her through the streets to the Caesareum, a former temple converted into a church, where she was stripped, flayed with shards of pottery, and burned.18 Her death, in Socrates’ account, was not a spontaneous riot but an act carried out with deliberate cruelty, intended to erase both her body and her philosophical legacy.

This brutality cannot be separated from the institutional context that enabled it. The parabalani operated under episcopal oversight yet were largely beyond civic control. Theodosius II’s laws had restricted their number after repeated disturbances, but enforcement was lax in Alexandria, where Cyril’s influence eclipsed that of the imperial administration.19 The murder thus exposed a structural imbalance: an empire officially governed by imperial edict but effectively ruled in its provinces by ecclesiastical authority. Hypatia’s fate was the cost of that imbalance, a philosopher sacrificed at the altar of competing sovereignties.

The political aftermath was telling. Emperor Theodosius II issued no condemnation of Cyril, nor was any imperial inquiry successfully prosecuted. The prefect Orestes disappears from the record soon after, likely recalled or marginalized.20 Cyril, meanwhile, emerged stronger. Within a few years, he would preside over the Council of Ephesus (431 CE) and be celebrated as a Doctor of the Church. The silence surrounding Hypatia’s death became an early instance of what modern scholars might call sanctified impunity: violence legitimized by theological victory.

For contemporaries like Synesius of Cyrene, who had been Hypatia’s student and friend, her death represented the death of the Alexandrian ideal, a vision of civic harmony in which philosophy and faith could coexist.21 The philosopher’s body was destroyed, but her name endured as an indictment of the society that had turned its mobs into missionaries. Later chroniclers, such as John of Nikiu in the seventh century, would rewrite the event entirely, portraying Hypatia as a demonic pagan who led the people astray.22 What had once been murder became, in the Christian chronicle tradition, divine judgment. John wrote:

“And in those days there appeared in Alexandria a female philosopher, a pagan named Hypatia, and she was devoted at all times to magic, astrolabes and instruments of music, and she beguiled many people through her Satanic wiles. And the governor of the city honoured her exceedingly; for she had beguiled him through her magic. And he ceased attending church as had been his custom… And he not only did this, but he drew many believers to her, and he himself received the unbelievers at his house.”22

The reworking of Hypatia’s memory reveals the deeper function of her martyrdom. To her followers, she became a martyr of reason; to her enemies, proof that the triumph of Christianity required the purification of thought. The two visions were not reconciled but intertwined, each acknowledging that her death marked the point at which philosophy ceased to be politically neutral. In killing her, Alexandria extinguished not only a teacher but the last visible bridge between the classical and Christian worlds.

From Martyrdom to Myth: The Christianization of Power

In the decades that followed Hypatia’s death, her story passed from event to emblem. What had begun as a local act of fanaticism became a defining moment in the transformation of Christianity from a persecuted creed into an imperial system of governance. The same religion that had once been threatened by the sword now wielded it with sanctified authority. By the mid-fifth century, imperial legislation, ecclesiastical councils, and public sermons together forged a theology of rule: the emperor as protector of orthodoxy and the Church as custodian of civic order.23

The process had begun long before Alexandria’s violence. When Theodosius I declared Nicene Christianity the official religion of the empire in 380 CE, he effectively merged faith and citizenship.24 Paganism, Judaism, and heresy were not merely theological deviations but crimes against the state. The Codex Theodosianus codified this fusion, outlawing sacrifices, closing temples, and threatening philosophers who clung to “impious” studies.25 Hypatia’s death thus occurred not in a vacuum but within a juridical and ideological framework that equated pluralism with sedition.

Alexandria became a microcosm of this imperial theology. After the destruction of the Serapeum, the city’s surviving pagan institutions either Christianized or vanished.26 Monasteries replaced academies; bishops displaced civic officials. The intellectual freedom that had characterized Hellenistic scholarship was recast as dangerous autonomy. In that world, a philosopher who remained outside ecclesiastical patronage could no longer be tolerated. Hypatia’s murder, then, was not an aberration but the local expression of a broader pattern, the enforcement of doctrinal unity through coercive means.

The reworking of her image in Christian historiography completed the cycle of domination. In the Chronicle of John of Nikiu, written two centuries later, she is depicted not as victim but as villain, a woman “devoted to magic” whose death purged Alexandria of its last stain of paganism.27 Such revisionism served to sanctify both Cyril’s authority and the moral narrative of Christian triumph. The philosopher became the necessary scapegoat in the drama of faith’s victory over reason.

This transformation reflected what Peter Brown has called the “moralization of power” in late antiquity, the conviction that authority was legitimate only when exercised for spiritual ends.28 Yet the paradox of Hypatia’s death was that this sanctified authority depended on violence. Her murder revealed that the Christian empire, in seeking purity, had adopted the very instruments of persecution once used against it. From this synthesis emerged a new political theology: not merely the rule of emperors who were Christian, but the rule of Christianity itself through emperors, bishops, and mobs alike.

The Legacy of Hypatia and the Roots of Christian Nationalism

The story of Hypatia did not end in Alexandria. It echoed through centuries of Christian self-definition, resurfacing wherever faith aligned itself with political authority. Her death became the template for a broader historical rhythm, the fusion of divine mission and temporal power that would shape medieval Europe and persist into the modern age. What began as a theological victory in the streets of Alexandria matured into a political doctrine: the conviction that to defend the faith was to govern in its name.29

In the centuries following the fall of Rome, Christian rulers absorbed and refined this fusion. Constantine’s precedent and Theodosius’ decrees evolved into the medieval ideal of Christendom, where the legitimacy of kings derived from divine sanction. The papal coronations of emperors, the Inquisition’s policing of orthodoxy, and the suppression of heretical movements all drew on the same moral logic that had condemned Hypatia, that the unity of belief justified the suppression of dissent.30 The philosopher’s mutilation thus foreshadowed not only the silencing of paganism but the later silencing of any voice deemed impure, foreign, or corrupting to the Christian body politic.

By the Renaissance, Hypatia’s image began to change. Humanists and early Enlightenment thinkers reclaimed her as the martyr of philosophy, a secular saint of reason against clerical tyranny.31 Yet the deeper pattern she represented, the sacralization of power, remained intact. Whether in the religious monarchies of early modern Europe or the Protestant states that replaced them, Christian identity continued to provide the grammar of national authority. From Augustine’s City of God to the Puritan “errand into the wilderness,” theology supplied the moral vocabulary for empire.

This continuity reveals why Hypatia’s death still resonates in modern debates over Christian nationalism. The ideological core is the same: a belief that divine truth must govern public life, that spiritual purity demands political conformity, and that those outside the faith threaten both.32 In Alexandria, this logic produced a mob; in later centuries, it produced crusades, inquisitions, and colonial missions cloaked in moral righteousness. What binds them together is the transformation of faith into an instrument of rule.

To recall Hypatia is therefore to confront the earliest convergence of piety and coercion in the Western tradition. Her dismembered body, dragged through the streets that once celebrated learning, remains a metaphor for what happens when belief claims a monopoly on truth. Christian nationalism, ancient or modern, rests on that same exchange: knowledge traded for obedience, plurality for power. The philosopher’s blood did not end a debate; it inaugurated one that still defines the moral horizon of the West.33

Conclusion: The Meaning of Hypatia

The murder of Hypatia was not merely an episode of mob violence but the manifestation of a profound moral inversion within the late Roman world. The same empire that had once crucified Christians for defying civic religion now executed a philosopher for defying Christian authority. In that reversal lay the birth of a new political theology, one that confused sanctity with sovereignty and made orthodoxy the price of citizenship. Hypatia’s death revealed that persecution, once condemned as the empire’s sin, had become its sacrament.34

Yet her legacy endures because her life exposes a paradox that still haunts political religion: the conviction that divine truth requires human enforcement. When power seeks to purify, it always destroys what it claims to defend. Hypatia’s commitment to knowledge, dialogue, and civic peace offers a counter-vision to the coercive certainty that ended her life. Her classroom, where pagans and Christians studied side by side, embodied the pluralism that empires and nations alike must learn to preserve or perish.

The continuity from Alexandria to later Christendom to the modern politics of faith is not a straight line but a recurring pattern. Whenever religion merges with nationalism, Hypatia’s shadow reappears. Her story warns that the moment belief wields the sword, it ceases to be faith and becomes ideology. In that sense, she remains the first casualty of Christian nationalism and the most enduring witness against it.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Socrates Scholasticus, Historia Ecclesiastica, Book VII, chap. 15.

- Edward J. Watts, Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 24–29.

- Maria Dzielska, Hypatia of Alexandria (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 85–88.

- R. Malcolm Errington, Roman Imperial Policy from Julian to Theodosius (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 201–215.

- Christopher Haas, Alexandria in Late Antiquity: Topography and Social Conflict (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 11–16.

- Haas, Alexandria in Late Antiquity, 154–159.

- Averil Cameron, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, 395–600 AD (London: Routledge, 1993), 57–60.

- Watts, Hypatia, 73–77.

- Haas, Alexandria in Late Antiquity, 209–214.

- Synesius of Cyrene, Letters, trans. A. Fitzgerald (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1926), no. 154.

- Dzielska, Hypatia of Alexandria, 92–95.

- Peter Brown, Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992), 103–108.

- Socrates Scholasticus, Historia Ecclesiastica, Book VII, chap. 15.

- Cameron, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, 91–94.

- Codex Theodosianus 16.10.12–14, trans. Clyde Pharr, The Theodosian Code and Novels (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952).

- Watts, Hypatia, 105–110.

- Socrates Scholasticus, Historia Ecclesiastica, Book VII, chap. 15.

- Watts, Hypatia, 115–118.

- Haas, Alexandria in Late Antiquity, 213–217.

- Dzielska, Hypatia of Alexandria, 100–103.

- Synesius of Cyrene, Letters, trans. A. Fitzgerald (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1926), no. 137.

- John of Nikiu, Chronicle, trans. R. H. Charles (London: Oxford University Press, 1916), chap. 84.

- Cameron, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, 122–126.

- R. Malcolm Errington, Roman Imperial Policy from Julian to Theodosius (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 213–218.

- Codex Theodosianus 16.10.12–14, trans. Clyde Pharr, The Theodosian Code and Novels (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952).

- Haas, Alexandria in Late Antiquity, 248–252.

- John of Nikiu, Chronicle, chap. 84.

- Brown, Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity, 134–137.

- Watts, Hypatia, 142–145.

- Cameron, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, 198–202.

- Dzielska, Hypatia of Alexandria, 126–128.

- Brown, Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity, 138–142.

- Haas, Alexandria in Late Antiquity, 254–258.

- Errington, Roman Imperial Policy from Julian to Theodosius, 219–222.

Bibliography

- Brown, Peter. Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992.

- Cameron, Averil. The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, 395–600 AD. London: Routledge, 1993.

- Codex Theodosianus. Translated by Clyde Pharr. The Theodosian Code and Novels and the Sirmondian Constitutions. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952.

- Dzielska, Maria. Hypatia of Alexandria. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Errington, R. Malcolm. Roman Imperial Policy from Julian to Theodosius. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- Haas, Christopher. Alexandria in Late Antiquity: Topography and Social Conflict. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

- John of Nikiu. Chronicle. Translated by R. H. Charles. London: Oxford University Press, 1916.

- Socrates Scholasticus. Historia Ecclesiastica. Book VII.

- Synesius of Cyrene. Letters. Translated by A. Fitzgerald. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Watts, Edward J. Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.24.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.