By Dr. Diego Puga

Professor of Economics

College for Monetary and Financial Studies (CEMFI)

By Dr. Daniel Trefler

Douglas and Ruth Grant Canada Research Chair in Competitiveness and Prosperity

Professor of Economic Analysis and Policy

University of Toronto

Abstract

International trade can have profound effects on domestic institutions. We examine this proposition in the context of medieval Venice circa 800–1600. Early on, the growth of long-distance trade enriched a broad group of merchants who used their newfound economic muscle to push for constraints on the executive, that is, for the end of a de facto hereditary Doge in 1032 and the establishment of a parliament in 1172. The merchants also pushed for remarkably modern innovations in contracting institutions that facilitated long-distance trade, for example, the colleganza. However, starting in 1297, a small group of particularly wealthy merchants blocked political and economic competition: they made parliamentary participation hereditary and erected barriers to participation in the most lucrative aspects of long-distance trade. Over the next two centuries this led to a fundamental societal shift away from political openness, economic competition, and social mobility and toward political closure, extreme inequality, and social stratification. We document this oligarchization using a unique database on the names of 8,178 parliamentarians and their families’ use of the colleganza in the periods immediately before and after 1297. We then link these families to 6,959 marriages during 1400–1599 to document the use of marriage alliances to monopolize the galley trade. Monopolization led to the rise of extreme inequality, with those who were powerful before 1297 emerging as the undisputed winners.

Introduction

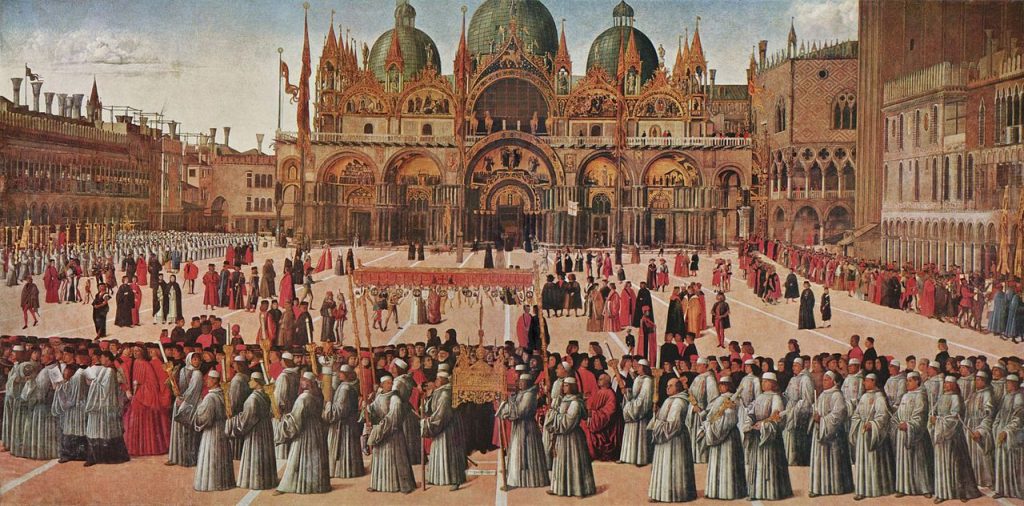

Venice has always presented two faces. As a great medieval trading center, its wealth was used to build not only beautiful architecture but also remarkably modern institutions. This is nowhere more obvious than in the Doge’s palace, whose grand Sala Maggiore housed a parliament (established in 1172) composed of the rich merchants that monitored and constrained most of the Doge’s activities. But after climbing up to the top floor of the palace, one enters the clandestine rooms of the secret service. With each passing decade after its establishment in 1310, this secret service was used to buttress the powers of a smaller and smaller number of families whose spectacular wealth was fed by international trade. This article tracks the evolution of Venice’s pre-1300 growth-enhancing institutional innovations and then the city’s dramatic post-1300 shift to political closure, social stratification, and extreme inequality at the top end. Our main thesis is that these developments were the outcome of the rise of international trade. International trade led to an increased demand for growth-enhancing inclusive institutions but also led to a shift in the distribution of income that eventually allowed a group of increasingly rich and powerful merchants to capture a large fraction of the rents from international trade.

Two strands of the literature are particularly relevant to this thesis, one dealing with medieval European trade (Greif 2006b) and the other with the Atlantic trade (Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson 2005). Medieval Europe experienced a massive expansion of long-distance trade during the Commercial Revolution of 950–1350 (see de Roover 1965; Lopez 1971; North and Thomas 1973). At the same time, medieval Europe embarked on a set of major institutional reforms that laid the groundwork for the rise of Western Europe. Greif (1992, 1994, 1995, 2005, 2006a,b,) establishes a causal connection between institutions and long-distance trade: Europe’s initial institutions facilitated the expansion of long-distance trade and, more important for our thesis, the resulting expansion of trade created a demand for novel trade- and growth-enhancing institutions. These included property rights protections that committed rulers not to prey on merchants (Greif, Milgrom, and Weingast 1994), a nascent Western legal system that included a corpus of commercial law known as the Law Merchant (Milgrom, North, and Weingast 1990), publicly provided monitoring and enforcement of commercial contracts (González de Lara 2008, 2011), and self-governing bodies such as business corporations. All of these are hallmark institutions of modern economic development.

Turning to early modern Europe, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2005) show that where pre-1500 political institutions placed significant checks on the monarchy, the growth of the Atlantic trade strengthened merchant groups to the point where they were strong enough to further constrain the power of the monarchy. The English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution are the most famous examples (Jha 2010; Acemoglu and Robinson 2012, chapter 7). After 1800, this improvement in property rights raised urbanization rates and income per capita.1

The foregoing research is pervaded by two themes that will be important for our analysis. First, institutional change occurs not because it is efficient, but because it is advanced by powerful special interests.2 Second, as trade grows it affects the domestic distribution of income and hence the relative power of competing special interests. This change in relative power drives institutional change.3

To deepen our understanding of the effects of long-distance trade, via income distribution, on long-run institutional dynamics, we turn to a detailed historical and statistical examination of Venice. The broad outlines of Venetian history that we use to support our thesis are as follows. Through “a series of fortuitous events” in the ninth century, Venice became politically independent (Cessi 1966, p. 261). Together with Venice’s unique geography, this positioned it to benefit from rising trade between Western Europe and the Levant. These two factors combined to enrich Venetian merchants, who used their newfound economic muscle to push for institutional change.

The two key dates for improvements in institutions that constrained the power of the executive are 1032, which marks the end of a de facto hereditary dogeship, and 1172, which marks the establishment of a Venetian parliament that became the ultimate source of political legitimacy. Contracting institutions also displayed extraordinary dynamism during the Commercial Revolution, in part to deal with the commitment and enforcement problems that come with doing business abroad (Milgrom, North, and Weingast 1990; Greif, Milgrom, and Weingast 1994; Greif 2006b) but also to deal with the unique demands placed on capital markets by long-distance seaborne trade. This risky trade required large capital outlays, and this in turn led to the development of new business forms and legal innovations that supported the mobilization and allocation of capital. One particularly famous innovation was the limited liability contract known as the colleganza in Venice and the commenda elsewhere in Europe. It was the direct precursor of the great joint stock companies of a later period. Importantly for our thesis, it allowed even relatively poor merchants—who had neither capital nor collateral—to engage in long-distance trade and profit from it.

These institutional improvements made Venice wealthier overall, and also led to other substantial changes in the Venetian distribution of income. For one thing, the riskiness of trade together with the widespread involvement of Venetians in this trade created a great deal of income churning—mostly rags to riches but also some riches to rags. For another thing, a small group of merchant families grew spectacularly wealthy.

This brings us to the great puzzle of Venetian history. During the period 1297–1323, a defining epoch in Venetian history known as the Serrata or “closure,” Venetian politics came under the control of a tightly knit cabal of the richest families. It was, in Norwich’s (1977, p. 181) words, the triumph of the oligarchs. Furthermore, by the early 1330s this political closure had spilled over into an economic closure that excluded poorer families from participation in the most lucrative aspects of international trade. Finally, by 1400 the political and economic closure had created a society characterized by a new emphasis on rank and hierarchy. In short, after 1323 there was a fundamental societal shift away from political openness, economic competition, and social mobility and toward political closure, extreme inequality, and social stratification.

To understand this puzzle, we construct a model that highlights the key role played by the evolution of income distribution. To this end, we introduce political and coercive institutions into a version of the Banerjee and Newman (1993) framework in which wealth dynamics are driven by occupational choice under wealth constraints (see also Galor and Zeira 1993).4 In our model, as was the case in medieval Venice, political power is tied to mercantile wealth. Along the model’s equilibrium path there is economic and political mobility until the wealthiest merchants are powerful enough as a group to restrict entry into political markets. However, long-distance trade continues to generate wealth for up-and-coming merchants, which poses a political and economic threat to the wealthiest merchants. To prevent this without triggering a revolt, the wealthiest merchants co-opt the nouveau riche by allowing them into the Great Council. This larger coalition then restricts participation in long-distance trade to Great Council members. Barriers to entry into both political and economic markets are erected. The resulting evolution of the distribution of income (and hence of coercive power) permanently supports this outcome.

We show empirically how this replicates the sequence of historical events associated with the Serrata of 1297–1323. The key outcome of the Serrata was the creation of a hereditary nobility that had the exclusive right to sit in the Great Council and used this right to restrict participation in long-distance trade. To deepen our understanding of the Serrata, we develop a database of the 8,178 elected members of the Great Council in the period immediately preceding the Serrata (1261–1296). We use this to show that mobility was indeed eroding the political position of the wealthiest families. In particular, they were losing seats to up-and-coming families who had not previously been involved in politics. Building on Kedar (1976) and González de Lara (2008), we code up hundreds of colleganza contracts for long-distance trade that have survived from the period 1073–1342. We use these to show that economic restrictions enacted during the Serrata were effective not only in restricting the use of the colleganza to the newly created nobility but in restricting it to the most powerful of these nobles.5 We then turn to the galley trade, the most lucrative aspect of long-distance trade. After the Serrata, control over state-sponsored galley convoys was restricted to nobles. To finance them, nobles abandoned the colleganza in favor of within-family financing and marriage alliances with other wealthy noble families. We track 6,959 noble marriages recorded during 1400–1599 using techniques from social network theory (Jackson 2008). We show that families who dominated the post-Serrata galley trade were the most important families in the marriage network (as measured by eigenvector centrality). We also show that these same families dominated the Great Council during 1261–1296. Thus, those who were powerful before the Serrata emerged from it as the undisputed economic, political, and social victors.

This article has three points of contact with the vast literature on Venetian history. First, the article deals with the so-called myth of Venice. In its strongest form, the myth states that the civic-minded Venetian patriciate acted selflessly in the interest of all Venetians and that the Serrata was not a major point of discontinuity. See Grubb (1986) and Martin and Romano (2000) for reviews of the literature. The myth has faced a number of criticisms, of which this article is one. Our post-Serrata analysis borrows threads from influential studies by Queller (1986) and Ruggiero (1980) discussed below, while our interpretation of the 1297–1323 Serrata is closest to Cracco (1967). However, we agree with Lane (1968) that Cracco’s emphasis on class struggle is misplaced and that more evidence is required to support his thesis. Rather than appeal to class struggle, we focus on special interest politics and institutions as in Acemoglu and Robinson (2006) and Greif (2008). Second, the article deals with Venetian social history. We integrate the late fourteenth century social transformation emphasized by Romano (1987) and Chojnacki (1997) into our broader thesis. Third, this article has implications for the literature on Venice’s long-term stability, particularly Venice’s ability to put a lid on interclan rivalries (e.g., Lane 1971, pp. 259–260; Greif 2006b, section 6.4.2; González de Lara, Greif, and Jha 2008). Our analysis of the distribution of economic rents complements Greif’s as well as González de Lara’s (2008, 2010, 2011) analyses of the self-reinforcing nature of constraints on the Doge and the role of policies to sustain rents from international trade. Note that because the very important issue of interclan rivalry is dealt with by these authors, we have little to say about it here. Finally, what sets us apart from the existing literature is our central thesis, namely, that international trade had profound long-term impacts, via wealth distribution, on domestic institutions. We support this thesis with systematic evidence covering eight centuries and tracking Venetian families’ political representation, involvement in international trade, and intermarriage.

Sections II–III review constraints on the executive and the rise of contracting institutions during Venice’s early history. Section IV presents the model. Section V reviews the Serrata and presents our empirical results about political mobility and the use of the colleganza. Section VI reviews the post-Serrata galley trade and our empirical results about marriage alliances and inequality. Section VII concludes.

The Rise of Constraints on the Executive

Overview

Throughout the ninth and first half of the tenth centuries, Venice experienced a slow revival of long-distance trade (McCormick 2001, pp. 630–638; Findlay and O’Rourke 2008, p. 84). This trade required Venetian merchants to cooperate in mobilizing resources, and in this period we already see numerous examples of Venetian convoys traveling throughout the Mediterranean (McCormick 2001, pp. 523–529). Furthermore, Venetian naval strength was growing. Venetian navies fought the Arabs in southern Italy in 827, 828, 840, and 842, though often unsuccessfully. However, by the 860s, Venetian naval power had become an effective deterrent to Arab naval actions (Nicol 1988, pp. 26–33). Explaining the origins of this success in collectively mobilizing resources is beyond the scope of our article because it would require both cross-cultural and cross-regional comparisons. We therefore restrict ourselves to two conjectures. First, (Greif 2006b, pp. 25–26) argues that when comparing Western Europe to the Islamic world, Western society made more allowance for individualistic as opposed to kin-based organizations, legitimized these organizations without appeal to religious authority, and thrived under the radar of relatively weak as opposed to strong states. All of these factors are pertinent to Venetian success.6 Second, unlike many Western European cities, the geography of the Venetian lagoon created an environment that discouraged agriculture and encouraged seaborne trade. Success in the latter required Venetians to cooperate among themselves.7

Constitutional Change I: The End of Hereditary Doges (810-1032)

Long-distance trade picked up substantially in the second half of the tenth century as a result of events in Western Europe and the eastern Mediterranean. To the west, rising incomes led to a resurgence of trade, especially along the Rhine and Danube Rivers north of Venice and the Po Valley emptying into the Venetian lagoon.8 To the east, between 961 and 969, a resurgent Byzantium regained control of the eastern Mediterranean sea lanes, notably conquering Crete and Cyprus. As Pryor (1988, p. 111) writes of these conquests: “Christian reconquest of the Muslim possessions along the trunk [main shipping] routes in the tenth and eleventh centuries laid the foundations for the later Western domination of those routes, with all that implied. The reconquest thus appears as one of the most fundamentally important historical processes in Mediterranean history.” Larger scale trade between Venice, Constantinople, and the Levant quickly reemerged. Figure I shows the main eastern Mediterranean trade routes.

The rise of long-distance trade had an important implication for Venice: it allowed a relatively large number of merchants to become rich and demand civic recognition. Evidence of this can be gleaned from the lists of endorsers of dogal documents. Endorsing a dogal document was a sign of having arrived in society. In the second half of the tenth century the number of endorsers per document increased considerably. Castagnetti (1992a,b) has carefully tracked the names appearing in three extant Venetian dogal documents from 960, 971, and 982. These documents were endorsed by 65 people in 960, 80 people in 971, and 128 people in 982. More interestingly, the percentage of endorsers belonging to families whose names had never before appeared in any Venetian document is high, averaging 59%.9

While these newly rich merchant families were not individually powerful, within 60 years of reopening the Mediterranean sea lanes to Christian shipping, they were collectively powerful enough to significantly constrain the power of the Doge. To analyze this process, one must bear in mind that dogal institutions in this period present two faces. On one hand, Doges were weak in that they were elected and often murdered or forced into retirement by their opponents. They were not autocrats. See, for example, Greif (1995, p. 738).10 On the other hand, Doges had wide-ranging powers that no other Venetian commanded. Cessi (1966, p. 270) describes the dogal system of the time as “quasi-tyrannical,” and Lane (1973, p. 90) writes that “the Doge was a monarch of unlimited power.”

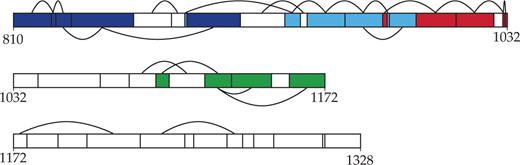

These two contradictory faces of dogal power pose a problem for us. To analyze constraints on the executive we must first establish that the executive was in fact at least somewhat powerful, even if not as powerful as claimed by Cessi and Lane. To do so we focus on one of the more important powers that a monarch can have, namely, the ability to appoint a family member as successor. Specifically, we consider succession from 810 (when the first Doge recognized by Byzantium was elected) until 1328 (when the last Doge of the Serrata period died).

Figure II illustrates the dynastic connections among Venetian Doges from 810 to 1328.11 Time is measured horizontally, and the length of each box corresponds to the length of the term in office of one Doge. For each Doge we go back in time to his most recent predecessor with whom he had a family connection. Curves above the box mark connections between father and either son or brother. Curves below the box mark connections involving a son-in-law or nephew. We break the Figure II bars at the two key constitutional crises of 1032 and 1172. We define a dynasty as a set of Doges who pass on the Dogeship within the family at least twice. In the figure, we mark each dynasty with a distinct color. There are three dynasties between 810 and the introduction of the first constraints on the Doge in 1032. The striking fact is that during this period, every Doge had a direct family relationship to another Doge and most Doges belonged to one of three dynasties.

The first dynasty, the Participazio, consists of Agnello Participazio, his sons Giustiniano and Giovanni Participazio, as well as Pietro Tradonico, who had married into the Participazio family, and Pietro’s nephew Domenico Tribuno. The four boxes that are not colored in the figure in this early period are also Participazio, but it is not clear from contemporary sources whether they were related to the earlier Participazio.12 The second dynasty, the Candianos, held the Dogeship for four successive generations (Pietro Candiano i, his son Pietro Candiano ii, his grandson Pietro Candiano iii, and his great-grandson Pietro Candiano iv). This was followed by Pietro Candiano iv’s brother (Vitale Candiano) and son-in-law (Tribuno Menio). The Orseolo were the third and final dynasty of the period. Doge Pietro Orseolo i was succeeded by his son Pietro Orseolo ii in 991, who in turn was succeeded by his son Otto in 1009. As was common for Doges, Otto used his position to appoint brothers to the most important church positions. One brother was appointed head of the Venetian church (patriarch of Grado), and another was appointed to a rank just below this (bishop of Torcello). In 1026, an already unpopular Otto blocked the appointment of a Flabanico family member to an important church position (bishop of Olivolo), which sparked a successful revolt led by Domenico Flabanico and resulted in Otto’s exile. Otto almost regained power during 1031–1032, but Domenico Flabanico prevailed and became Doge in 1032.

The election of Flabanico as Doge was a transformative moment in Venetian history. He was a wealthy silk merchant, and most subsequent Doges over the next many centuries were also merchants involved in long-distance trade. Flabanico’s election thus represents the triumph of the merchants. Further, his reign ushered in two de facto constitutional innovations that significantly constrained the powers of Doges. First, the election of the Doge was to be respected in full: a Doge would no longer be allowed to appoint his successor. Second, Doges were henceforth required to consult with a two-member dogal court of judges and abide by the court’s decisions (see Lane 1973, p. 90; Cessi 1966, p. 263 and 270). The constitutional principles embodied in these changes were not new—in principle, a Doge’s successor was elected rather than appointed and was accountable to judges. What was new was the willingness of subsequent merchant Doges to respect constitutional principles. This willingness is apparent in Figure II. Comparing the period 810–1032 with 1032–1328, there is a dramatic fall in the number of dogal successions, that is, in the number of lines connecting boxes. Furthermore, there is only a single dynasty after 1032.

The driving force behind the 1032 constraints on the executive was long-distance trade and the broad-based economic and political power it brought to a growing group of merchants. It is no coincidence that the reforms came relatively quickly after the opening up of eastern Mediterranean sea lanes to Christian shipping.13

Constitutional Change II: The Establishment of a Parliament (1032-1172)

From 969 on, Venetian long-distance trade expanded steadily; however, the growth of trade accelerated after 1082. In that year, a remarkable confluence of events on distant shores propelled Venice into a period of unprecedented prosperity and globalization.

In 1071–1081, Constantinople was again in decline, weakened by Seljuk Turks in Anatolia and facing invasion by the Norman kingdom in southern Italy. A desperate Byzantium enlisted Venetian naval aid to stop the Normans’ Adriatic crossing. Byzantium was in dire straights, and Venice extracted a heavy price for its naval involvement. The Golden Bull of 1082 granted Venice duty-free access to 23 of the most important Byzantine ports and granted Venetian merchants property rights protections from the caprices of corrupt Byzantine administrators. Most important, the Venetians were given buildings and wharfs within Constantinople. Venetians thus became the first foreign traders in Constantinople to have their own quarter. See Brown (1920) for an English translation of the Golden Bull and for details of the Venetian quarter.

The 1082 Golden Bull was crucial to Venice’s maritime expansion. As a result, the number of newly rich merchants who were eager for civic participation increased. In the 1090s we again see a jump in the number of new names endorsing dogal documents (see Castagnetti 1992b and especially Castagnetti 1992a, pp. 625–626 and 637–638).14 The time was ripe for merchants to once again flex their political muscle.

After the reign of four unrelated and long-lived Doges (see the middle bar in Figure II), the Michiel family held the Dogeship for 53 of the 75 years leading up to 1171.15 Toward the end of this period, Venetian–Byzantine relations had become increasingly acrimonious, and tensions came to a head on the night of March 12, 1171, when the Byzantine emperor rounded up 10,000 Venetians residing in the empire and announced that they were being held for ransom.16 In September 1171, Doge Vitale Michiel ii launched a large armada that was to blockade and harass Constantinople until the hostages were released. The plan failed miserably, and in May 1172 the fleet returned in utter disarray. Venetian frustration was palpable, and much of it was directed against the Doge. At a gathering on May 27, he was mobbed and assassinated. It had been almost two centuries since a Doge had been murdered, and the unexpected assassination left a power vacuum which the dogal court and leading merchant families immediately filled. As in Jones and Olken (2009), the assassination of a powerful ruler produced a transition to a less autocratic regime.

The first major change was the introduction of a limited-franchise elected parliament known as the Great Council.17 With this constitutional change in place, the new legislative body used its power to increasingly constrain the power of the Doge over the next few decades. Many of these constraints were formalized in the oath of office that the Doge now publicly swore to uphold. The oath explicitly listed what the Doge could not do, for example, expropriate state property or preside over cases against himself. The Great Council added to this list with the election of each new Doge (Hazlitt 1966, p. 437; Madden 2003, pp. 95–101). Furthermore, in all important decisions the Doge was required to consult with a strengthened six-member dogal council that was elected by and accountable to the Great Council. As Madden (2003, p. 98) notes: “In short, by 1192 the doge could do almost nothing without approval of the council.”18

The establishment of the Great Council and the constraints imposed by the dogal oath of office were major institutional innovations. For Norwich (1977, p. 90) these were “arguably the most important reforms in Venetian history.” They dramatically limited the power of the Doge and arrogated his powers to a large group of families who owed their wealth and power to long-distance trade.

Institutional Change: The Rise of Contracting Institutions and Inclusive Growth

Overview

The two centuries following 1082 were ones of extraordinary dynamism for contracting institutions. By the early fourteenth century, financial innovations included: the appearance of limited-liability business forms; thick markets for debt (especially bills of exchange); secondary markets for a wide variety of debt, equity, and mortgage instruments; bankruptcy laws that distinguished illiquidity from insolvency; double-entry accounting methods; business education (including the use of algebra for currency conversions); deposit banking; and a reliable medium of exchange (the Venetian ducat). All these innovations can be related directly back to the demands of long-distance trade.19

Equally important is the development of a supporting legal and enforcement framework. The most discussed of these is the Law Merchant, which is universally accepted as the foundation of modern commercial law (Berman 1983). Its very scope—the use of a court of peers to adjudicate commercial disputes between merchants traveling in distant lands—means that the Law Merchant was a direct and immediate response to the needs of long-distance trade (Kadens 2004).20 The Commercial Revolution is also viewed as a key driver of the development of the modern Western legal tradition. This tradition has its origins in a legal revolution that occurred in the period 1075–1122 (Berman 1983; Landau 2004). While a general discussion of the origins of this legal tradition is outside the scope of this article, a comment on timing is appropriate. Civil law was not in use anywhere in Europe in 1000 (Radding and Ciaralli 2006), but reemerged in Europe in the second half of the twelfth century when communes began writing statutes governing their constitutions and commerce (Landau 2004). Second, the first half of the twelfth century witnessed an explosion of secular legal documents. Such documents were rare in 1050 but common by 1150.21 Venetian law developed rapidly thereafter: its codification was begun under Doge Enrico Dandolo (1192–1205) and completed in 1242 by Doge Jacopo Tiepolo (1229–1249). See Besta and Predelli (1901).

Thus, civil law and commercial documents both appear just after long-distance trade began its explosive growth. There were other developments in Venetian contracting institutions in this period. See, for example, González de Lara (2008, 2011). Here we simply conclude that the expansion of trade after 1082 was accompanied, especially toward the end of the twelfth century, by a remarkable set of innovations in contracting institutions.

The Colleganza as an Institutional Response to the Demands of Long-Distance Seaborne Trade

We now take an in-depth look at one particular contracting innovation—the colleganza. This was a predecessor of the joint-stock company and is viewed by economic historians as one of the key commercial innovations of medieval times, if not the key innovation (e.g. Lopez and Raymond 1967, p. 174). Our main aim is to draw out the implications of long-distance trade for the evolution of income distribution and set the stage for the empirical work to come. For further details on the colleganza and comparisons with other contemporary commercial contracts, see Lopez and Raymond (1967), Pryor (1987), and González de Lara (2010).

To understand why the colleganza was such an innovation, one must first understand the mechanics of long-distance trade. Ships typically left Venice at the end of March when the winter storm season was finished and the prevailing winds had turned favorable. If all went well, ships arrived in Constantinople by the end of April, spent three weeks collecting merchandise for the voyage home, and arrived back in Venice by July. The goods brought back were then sold to merchants traveling to the late summer fairs in Central and Western Europe. See Lane (1966, 1973, pp. 69–70). Such a trip, if on schedule, would have earned enormous profits—over 100% and sometimes much more. Although big returns could be had, there were also big risks. Death abroad from illness, shipwrecks, and piracy were common. There was also substantial business risk associated with the thinness of markets. Ships often traveled from port to port for months while merchants searched the hinterland for merchandise. A merchant who arrived in Acre a month late might find that the market was over for the year and be forced to dump his goods at fire sale prices. Thus, luck and also the business skills and effort of a traveling merchant could make the difference between huge profits and huge losses.

The colleganza was a solution to three key problems of long-distance trade. First, this trade required large amounts of capital relative to most other contemporary private commercial activities, such as agriculture or manufacturing. Second, collateral was problematic because, unlike in agriculture or manufacturing, the capital literally sailed out of sight. Third, the complex unforeseeable circumstances and large risks involved required balancing high-powered incentives for traveling merchants with risk sharing between them and the investors.

Although there were many variants of the colleganza, we describe only the simplest and most common of these. There are two parties, the traveling merchant and the investor (or sedentary merchant). In Venice, the sedentary merchant gives cash or wares to the traveling merchant, who then boards a ship with other merchants for an overseas destination, say, Constantinople. In Constantinople, the traveling merchant sells the wares and uses the proceeds to buy other wares for resale in Venice. A colleganza specifies the names of the two parties, itemizes the capital contributed by the sedentary merchant and/or gives it a value (this is the “joint stock”), and states how profits will be split. The contract sometimes provides specific instructions, for instance, an itinerary of ports to be visited, but very often leaves the traveling merchant a very high degree of freedom. Once the traveling merchant brings or sends the wares back to Venice, the accounts of the voyage are settled and the relationship is dissolved. In the archetypical colleganza, the sedentary merchant provides all the capital and receives 75% of the profits. The traveling merchant contributes no capital and receives 25% of the profits. If there are losses, these come out of the sedentary merchant’s capital. However, the sedentary merchant’s obligations are limited by his initial investment. Restated, the colleganza provides limited liability and, specifically, the liability is limited to the joint stock specified in the contract. This was a major innovation over Roman law and is widely recognized as the origins of the great joint stock companies of a later period.

Figure III provides a typical example. The sedentary merchant, Giovanni Agadi, puts up the joint stock of 300 pounds of Venetian pennies, an unimaginable sum for an ordinary Venetian. The traveling merchant, Zaccaria Stagnario, is to board a privately owned ship that will travel in convoy to Constantinople. No other commercial instructions are given: Stagnario is in charge of all other decisions (including continuing his voyage to “any other place that seems good to me”) and this is why high-powered, profit-sharing incentives are needed. The profit split is expressed in fractions: three fourths for the sedentary merchant and one fourth for the traveling merchant. If instead of profits there are losses, this downside risk is entirely borne by the sedentary merchant: “at your own risk from sea and people.” The traveling merchant faces stiff penalties for failure to pay back the sedentary merchant.22

There is much that is not specified in this contract, so much so that the contract is hard to understand except in the context of supporting institutions that developed to support merchants traveling in colleganza. This point comes out in Pryor (1987, chapters 3 and 4), who reviews the resolution of hundreds of colleganza disputes to flesh out the full set of “rules of the game” surrounding the colleganza. In addition, González de Lara (2008, 2010, 2011) reviews the private and public institutions that supported the colleganza in Venice in the thirteenth century. Thus, the colleganza is not just a contract, it is an innovation that created a demand for other supporting institutions.

Economic and Political Mobility: The Role of the Colleganza

The discussion of this section has emphasized that long-distance trade was exceptionally complex and risky and could make or break a merchant. It has also emphasized that the institutional response—the colleganza—allowed poor merchants to enter the game. Indeed, most historians have commented on this feature of the colleganza, for example, de Roover (1965, p. 51), who writes: “In a great many cases, the tractores [traveling merchants] were ambitious young men who were willing to take heavy risks in order to accumulate sufficient capital to join eventually the ranks of the stantes [sedentary merchants].”

As a result of the widespread engagement of the population in long-distance trade and the economic mobility it entailed, newly rich merchants flowed into political power throughout the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. This is a famous feature of Venetian society at this time. See Hazlitt (1966, p. 216), Lane (1973, p. 20, 89–90), Norwich (1977, pp. 182–183), Ruggiero (1980, p. 4), and Lopez (1971, pp. 67–68, 70). In Madden’s (2003, p. 3) words, “the membrane of Venetian nobility was permeable. Indeed, nobility in the sense of a group of families with a hereditary claim to political authority did not exist at all. In Venice, wealth, not land, defined nobility; commercial skill, not military prowess.”

The life of Zaccaria Stagnario provides an example of the economic and political mobility that was possible at this time. His grandfather Dobramiro was a Croatian slave who was freed when his Venetian owner died. His father, Pancrazio, was a helmsman. In 1199 we find Zaccaria traveling in colleganza to Constantinople (this is the document we reproduced and translated in Figure III), and this experience paid off handsomely when he moved there after the 1204 conquest. By 1207 he held office as councilor to the first Venetian podestà in Constantinople and was rich enough to be a sedentary merchant in two colleganzas for the large sum of 200 Byzantine hyperpeppers, an amount equal to seven months’ salary of the Duke of Crete. Ironically for the grandson of a slave, these colleganza were for travel to the Black Sea fortress of Sudak, a slave-trading center. Upon his return to Venice, Stagnario integrated himself into the highest social and political circles. In the words of Robbert (1999, p. 35): “Zaccaria, the grandson of a slave, represented the new man in Venice who climbed to the top because of his business skills.”23

Colonial Empire and Nobility Rents, 1082-1297

On April 12, 1204, the blind Doge Enrico Dandolo ordered his galley beached under the imposing walls of Constantinople. He urged his men up and over, where they entered the history books as the first foreigners ever to enter Constantinople by force. Constantinople fell, and in the upheaval that followed, Venice grabbed a vast swath of colonies spread throughout the Aegean, eastern Mediterranean, and Black Seas. Over the next half century, upward of 70,000 Venetians migrated to these colonies, creating a vast commercial network within a colonial empire.

To run its colonial empire, Venice quickly established a colonial bureaucracy. At its apex stood a relatively small number of chief colonial administrators.24 They occupied extraordinarily lucrative offices: large salaries were paid by the Venetian state (e.g., Robbert 1994, tables 4–8) and officeholders “usually mixed business with politics” (Lane 1973, p. 141). Rösch (1989, pp. 160–161) documents that within just three years of the 1204 conquest, nine Venetians had already earned vast profits. By the time of the Serrata in 1297–1323, chief colonial administrators were often drawn from the richest families of the newly formed nobility (O’Connell 2009, chapter 2). We therefore refer to the benefits of officeholding as nobility rents. There were many other forms of nobility rents, and we focus on this one for simplicity.25

The Puzzle and a Model

We have described a virtuous circle: long-distance trade created a constituency that supported improvements in public and private institutions, and these improved institutions supported the further growth of trade. However, the fourteenth century witnessed a marked decline in economic, political, and social mobility. In the years 1297–1323, the Serrata created a closed hereditary nobility, and in the decade after 1323 this nobility put a stranglehold on the most lucrative lines of long-distance trade.

To understand the events of 1297–1323 and their long-term consequences for Venice’s institutions, we develop a model that highlights how wealth dynamics interact with politics to drive institutional change. In this section, we present the key ingredients and implications of our model. A complete formal presentation can be found in the Appendix.

We build on Banerjee and Newman (1993), in which individuals are motivated by their own material well-being and the bequest they leave for their children. Initial wealth limits the occupational opportunities available to credit-constrained individuals, and this in turn affects wealth dynamics. We tailor the occupation and investment opportunities to our Venetian setting and also add in political economy considerations. In the model, all Venetians can initially participate in international trade. Those without much capital of their own can either remain in Venice as craftsmen or become traveling merchants by signing a colleganza contract with a sedentary merchant, who will put up the required capital. Those with intermediate wealth can finance their own voyage. Finally, the very wealthy can be sedentary merchants in multiple colleganza. International trade is risky, and the success or failure of commercial voyages drives economic and social mobility.

As usual, this type of model is tractable if one focuses on parameter configurations such that children’s occupational choices depend on their parents’ wealth bracket (low or L, medium or M, and high or H) and the success or failure of their parents’ projects, but not on the parents’ specific wealth levels within each bracket. Rather than analyzing every possibility, we focus on a case that captures key elements of the evolution of international trade and political institutions in Venice. Figure IV represents this case on a simplex where we can follow the evolution of Venice’s wealth distribution. The share of low-wealth individuals, denoted PL, is measured along the horizontal axis, the share of high-wealth individuals, denoted PH, is measured along the vertical axis, and the share of middle-wealth individuals is given implicitly by PM = 1 − PL − PH. Assume an initial wealth distribution with a mixture of low- and middle-wealth individuals, but very few high-wealth individuals, which corresponds to a point like A on the simplex and characterizes Venice in its early days. In addition, parameters for the returns from international trade and the probability of success and failure are chosen so that, consistent with our earlier discussion, international trade creates substantial mobility, some of it downward but mostly upward. The corresponding differential equations, and the patterns of intergenerational mobility that underlie them, can be found in the Appendix.

Starting from point A, over time commercial success allows some middle-wealth individuals and their children to join the high-wealth group, while failure makes others join the low-wealth group. This makes the wealth distribution move upward and rightward on the simplex toward point B.26 When the size of the group of high-wealth individuals who operate as sedentary merchants increases sufficiently, this reduces their profits. In the model, this is captured in a very simple way. Each sedentary merchant signs colleganza contracts with μ traveling merchants, drawn from the group of low-wealth individuals. When the wealth distribution crosses the PL = μPH line at point B, all low-wealth individuals are now working as traveling merchants. Any further increase in high-wealth individuals (PH) creates competition among them for traveling merchants, which bids up costs and reduces expected profits for sedentary merchants. This increases wealth churning: the poor are now more upwardly mobile and the rich are now more downwardly mobile. As a result, the economy moves toward the steady state at C.

The high degree of intergenerational mobility and churning that characterizes this steady state was preempted, as we shall see, by political developments. To capture these developments, we add in coercive political economy considerations. In line with the historical evidence that membership in the Great Council was initially tied to commercial wealth, in our model the council is made up of individuals who are born to wealthy families as well as those with a more modest background who become wealthy over the course of their lifetime through commercial success. However, Great Council members can vote to prevent further entry into the council by making membership hereditary. This allows existing Great Council members to keep all of the rents associated with political power for themselves, but may trigger a violent revolt by those who are excluded. We model the revolt technology in a simple way so that its outcome depends on the relative size of the groups supporting the revolt and opposing it. A vote to close the Great Council benefits its PH members and harms the PM individuals with middle wealth who could potentially gain entry for themselves and their children through commercial success. Thus, a revolt against such political closure succeeds whenever βPH < PM, where β > 1 captures the fact that Great Council members are more powerful because they control the state’s coercive capacity. Since PM = 1 − PL − PH, the revolt condition becomes:

If this condition is not met, then a revolt is defeated and its participants are hanged in St. Mark’s Square.

Figure IV illustrates the timing of closure, that is, the timing of the Serrata. As society moves from point A to point B, international trade creates a rising group of very wealthy merchants. As trade continues to feed the joint wealth and power of this group, which is amplified by their control over the coercive power of the state, eventually the group becomes powerful enough that it can close the Great Council without a successful revolt by up-and-coming merchants. This happens when the wealth distribution crosses the line

at point S. (S stands for Serrata.) Before this point, if members of the Great Council had voted for the Serrata they would have faced a successful revolt. After point S, members of the Great Council are powerful enough as a group to vote for hereditary membership without facing a revolt. From that point on, a person becomes a member of the Great Council only if his father was a member: Membership, which until then had been associated with commercial wealth, becomes hereditary. A formal nobility is established and equated with membership in the Great Council. This prevents further erosion of political rents through mobility into the Great Council.

After the Great Council becomes hereditary, many nonmembers continue to accumulate high wealth through commercial success. As they do so, these commoners become sedentary merchants and compete economically with nobles (Great Council members), all of whom are sedentary merchants. This competition squeezes the profits of nobles and, in particular, at point B the expected profits of sedentary merchants drop discretely.27 Nobles then have a strong incentive to impose economic restrictions on commoners. A second restrictive measure voted by the Great Council can exclude nonmembers from investing in international trade. Restrictions on trade help nobles by preserving high profits for their commercial activities. The downside is again that this may trigger a violent revolt by those who are negatively affected. Excluding commoners from international trade harms a larger segment of Venetian society than did excluding commoners from the Great Council. Specifically, it reduces the expected earnings of commoners. At the time of the Serrata restrictions on trade would trigger a successful revolt.28 Thus, to restrict investment in trade, nobles need to co-opt some of the nouveau riche commoners who had recently gained high wealth through commercial success but had been excluded from the Great Council. They can do this by increasing membership in the Great Council to

so that βPN = 1 − PN, that is, so that a revolt would be defeated. As we shall see, this increased membership is referred to in Venetian history as the enlargement of the Great Council. With this influx of new members, the Great Council is tremendously powerful: membership defines nobility status, and commoners are excluded from the highly lucrative long-distance trade.

In Figure IV, as a result of the restrictions on investing in international trade, the wealth distribution moves rightward from point B to point D instead of moving from B to C. Despite the political and economic closure, while moving toward point D, Venice continues to engage in international trade. However, compared with the evolution toward C that Venice would have followed absent any restrictions, a smaller fraction of Venice’s population is involved in international trade, a larger fraction is involved in manufacturing, Venice’s wealth distribution is more polarized, and social and economic mobility is reduced to a minimum.

To summarize, our model features a Serrata-like event with four key characteristics. First, following a phase of substantial mobility into the Great Council, the council passes measures that implement both political and economic closure. Since restrictions on Great Council membership harm a smaller share of Venetians than do restrictions on participation in the most lucrative aspects of trade, the latter come about later in the process and are preceded by co-optation. This co-optation involves an enlargement of the Great Council that admits more wealthy merchant families. For those who are admitted, their descendants are ensured a seat in the Great Council and a share of the nobility rents, even if those descendants become impoverished. Second, participation in the most lucrative aspects of international trade and in politics become based on family lineage and not on individual merit or commercial success. Third, closure leads to social stratification (decreased social mobility). Fourth, there is a shift in economic activity away from long-distance trade and toward manufacturing.

The Oligarchs Triumphant

Overview

In this section we review three key events in Venetian history through the lens of our model. First, we provide new evidence from the period 1261–1296 that mobility into and out of the Great Council was eroding the power of many established families. Second, we argue that this erosion is essential for understanding the Serrata of 1297–1323, the most important constitutional event in Venetian history. Norwich (1977, p. 181) describes the Serrata as “The Oligarchs Triumphant.” Third, we show that toward the end of this period and culminating in the early 1330s, a series of laws were passed that severely restricted the ability of non-nobles to engage in long-distance trade. Furthermore, among nobles, it was the most powerful nobles who benefited most from these restrictions.

The Changing Membership of the Great Council

We start with novel evidence that in the period leading up to the Serrata: (i) there was a high degree of mobility into and out of the Great Council; (ii) a majority of seats in the Great Council were held by a relatively small number of powerful families; and (iii) some of these families were losing seat shares to merchants who had not previously participated in the Great Council. To this end, we constructed a database on representation in the Great Council. A Great Council session lasted for one year, starting in October. The council recorded the names of its members and these lists have survived for each of the sessions in 1261–1262, 1264–1271, 1275–1284, and 1293–1296. The handwritten lists, together with other surviving records of Great Council deliberations, have been transcribed in the Deliberazioni del Maggior Consiglio di Venezia (Cessi 1931–1950).29

The lists are complex. They contain 8,178 legible names. As is well known, Venetian society in general and Great Council elections in particular were organized along family (i.e., clan) lines. See, for example, Raines (2003). It is therefore important to group individuals’ names into families. Most family names have multiple variants, and standardizing these was a lengthy and meticulous process.30

Figure V graphically portrays the extent of mobility into and out of the Great Council and the erosion of seat shares of families who were initially represented in the Great Council. Consider the dashed line. To construct it, we first rank all families based on their initial seat shares, that is, on the average number of seats the family held during the first three available sessions (1261–1262 and 1264–1266). For example, the Dandolo family (1 on the horizontal axis) held the most seats, 4.7% of the total. This 4.7% appears on the vertical axis. The Contarini family (2 on the horizontal axis) held 4.6% of seats, so that the cumulative seat shares held by these two families was 9.3%. This 9.3% is displayed on the vertical axis. Moving rightward along the solid line, 50% of the seats were held by 21 families, 75% of the seats were held by 52 families, and 100% of the seats were held by 162 families. This gives meat and precision to a common observation in the literature that among Venetian families, “between 20 and 50 might be considered great families” (Lane 1973, p. 100).

The solid line in Figure V presents the cumulative seat shares at the end of our sample, during the last three available sessions (1293–1296). We retain the ordering of names from 1261–1262 and 1264–1266 so that 1 is still Dandolo, 2 is still Contarini, and so on. Families that did not appear in this initial period are ranked by seat shares in the 1293–1296 period. (This is the concave section at the right end of the solid line.) Three features of Figure V stand out.

First, at the point where the dashed line reaches 100%, the solid line only reaches 87%. Thus, 13% of the end-period seats were held by families that entered the Great Council after the initial period. There were 50 such new families.31 This implies considerable mobility into the council. This was not simply entry of a bunch of small-time players. The seat shares of new families were highly skewed, as can be seen from the concavity of the final portion of the solid line. For example, the new family with the most seats was the Caroso family, who went from no seats to being 28th in the seat-share rank of the end period. Furthermore, most of the new families were engaged in long-distance trade, as evidenced by their appearance in commercial contracts. For example, the new family with the second-most seats was the Caotorta, for whom the surviving records include settlements of accounts with Zaccaria Stagnario for trade between Venice and Constantinople. The new families with the third-most and fourth-most seats, the Nicola and the Barastro, also appear in commercial contracts.32 These four merchant families, with no seats in the initial period, were all in the top 50 by seat shares in the end period. Their rank placed them among Lane’s great families. Thus, new families were quickly growing wealthy and politically powerful from long-distance trade.

The second feature of the figure is mobility out of the council. The flat portions of the solid line are due to families who initially had seats but ended up with none. There are 47 such families among the initial 162. This implies that the exit rate from the Great Council was 1.2% a year. This was nine times higher than the exit rate after the Serrata. For example, in the initial period the Dauro family held 1% of the seats and was ranked 29th, yet the family was no longer in the Great Council by the end period.33

The third and most striking feature of the figure is that the solid line (1293–1296) is well below the dashed line (1261–1262 and 1264–1266). Established families—even some of the most powerful—were losing seat shares. For example, the Falier family, one of the founding families of Venice, who had given the commune two Doges, held 2.5% of the seats and was ranked 6th in the initial period but by the end period its rank had dropped to 17th. Similarly, the powerful Zane family saw their seat rank drop from 9th to 26th.

In summary, this discussion surrounding Figure V shows that there was a high degree of mobility into and out of the Great Council, that new members were engaged in long-distance trade, and that the power even of great families was being eroded by up-and-coming families.

The Serrata, the “Enlargement of the Great Council,” and State Capacity for Repression

Wealthy families did not take this mobility lying down. Their attack began in the Great Council, where they introduced a series of motions aimed at gaining permanent control. After the failure of four such motions during 1286–1296, a landmark vote on February 28, 1297, effectively handed control of Great Council elections to a small number of powerful families.34 In particular, control over elections passed into the hands of the Council of Forty, a government organ “which had never before claimed a leading role in the state” (Rösch 2000, p. 74), and was controlled by older, powerful families.35 The initial Serrata motion distinguished between those who had served in the Great Council in the previous four years and those who had not. The former group was reelected automatically, provided they were supported by 30% of the Council of Forty (12 votes out of 40). The latter group had to overcome significant obstacles to membership, unless they had sat in the Great Council recently. Measures approved in 1298, 1300, and 1307 substantially strengthened this asymmetry between Great Council insiders and outsiders. Membership in the Great Council had taken a major step toward being locked in. See Hazlitt (1966), Lane (1971, 1973), Todesco (1989), and Rösch (2000).

Political closure was tightened with a series of laws that created a Venetian nobility. In 1310 the concept of nobility was formally introduced for the first time: a nobiles was a man “who was or could be a member of the [Great] Council” (Ruggiero 1980, p. 9). In 1319, the process for electing new members was eliminated. Henceforth, the only route to entry involved proving that a paternal ancestor had sat in the Great Council. The last of the Serrata laws was passed in 1323. It unequivocally made membership in the Great Council a hereditary position. Only men whose fathers and grandfathers had been in the Great Council could hold seats.36

Likely as a reaction to the Serrata, the period 1300–1355 was the most internally violent period in Venetian history from 976 to the demise of the Serene Republic in 1797. In early 1300, a popular commoner named Boccono along with 11 of his associates forced their way into the Great Council chambers. Boccono appears to have been intent on murdering several council members and brow-beating the remainder into reenfranchising those excluded by the Serrata. Arms were not permitted in the chambers, so Boccono and his associates represented a real threat, all the more so because they were backed by a crowd of armed supporters waiting outside in St. Mark’s Square. By a stroke of luck, an overheard conversation revealed the plot: the 12 conspirators were disarmed in the council chambers and executed that night. Their bodies were left hanging in St. Mark’s Square, where they served as a warning. In addition, 40 other supporters of the conspiracy were exiled and had their properties confiscated. See Ruggiero (1980, chapter 1).

Violence boiled over again on the night of June 15, 1310, when Venice was rocked by an armed insurrection. By luck, the plot was revealed the night before by a defector, and even this may not have prevented the insurrection: a violent storm wreaked havoc with communications between the two groups of insurgents who were converging on St. Mark’s Square, and the miscoordinated attack was repulsed. A successful revolt was barely averted. Ruggiero (1980, chapter 1) emphasizes that the motivation for this revolt was opposition to the Serrata.37

A sense of panic began to grip the elite: they might not be so lucky next time. It was time for a new, two-pronged approach that involved the building of coercive capacity and co-optation. The revolt occurred on June 15, 1310. On June 30, the Great Council declared martial law, and on July 10 the first meeting of the infamous Council of Ten was convened. The Council of Ten was initially tasked with tracking down the supporters of the revolt, but it evolved into the Venetian state’s repressive apparatus. From its beginnings, the Ten’s authority within the state hierarchy was left intentionally ambiguous. For example, it was not appointed by the Great Council nor accountable to it.38 Over time, the Council of Ten arrogated to itself whatever powers it needed. For example, in 1319 it created its own police force. Even this was not enough to quell the uproar over the Serrata, for in 1328 the Ten executed the Barozzi brothers for leading a conspiracy against the nobility. By mid-century, the Council of Ten had the necessary resources and experience to repress internal dissent, as evidenced by their speedy handling of Doge Falier’s 1355 attempt to overthrow the Great Council. This brought an end to the stormy period of post-Serrata violence.39

In addition to building up the state’s coercive capacity, the elite co-opted key potential opponents to the Serrata by granting them membership in the Great Council.40 This one-off enlargement of the Great Council is famous in Venetian history and happened quickly, essentially between 1297 and 1310.41 By the time membership of the Great Council became fully hereditary in 1323, its size had more than doubled from 415 members on average in 1261–1296 to around 950 members.42 To get a sense of the scale of the co-optation we have examined all 257 families that were present in the Great Council in 1323. One hundred fifty of these families had seats in the Great Council in 1293–1296 and so were essentially guaranteed hereditary membership. Another 107 families had no seats in 1293–1296 but were co-opted. These co-opted families included 31 who had sat in the Great Council recently, lost all their seats as a result of the intense churning during 1261–1296, and were brought back in. The remaining 76 co-opted families had not been in the Great Council during the period for which records exist (1261–1296). Thus, the Serrata made Great Council membership hereditary, locked in those Great Council members who had seats just before the Serrata (1293–1296), and co-opted many families who, if excluded, could have threatened the stability of the new system.43

The Closure of Long-Distance Trade

In the decade following 1323, the newly defined nobility passed a series of laws whose consequence was to limit participation by commoners in the most lucrative aspects of long-distance trade. The most important of these was the reorganization of the galley trade, although wealth-based restrictions on who could trade also played a role.

Galleys had long handled the most lucrative traded goods, including cloth, silk, cash, bullion, and spices (Lane 1963, p. 181). Their speed allowed them to escape capture by pirates, their maneuverability allowed them to stay together in convoys, and their small cargo holds made them impractical for anything but valuable lightweight goods. They were also excellent war machines. Toward the end of the Serrata the Venetian state completely overhauled the organization of the galley trade: instead of convoys of primarily privately owned and operated galleys, Venice moved to a system of publicly owned galleys that were auctioned off to private operators. Under the new system, which evolved rapidly between 1321 and 1329, the state chose the destinations and sailing dates of convoys of galleys and then auctioned off the galleys for the duration of the trip (muda). Crucially, “only nobles were allowed to participate in this auction, an exclusive privilege that gave them control of the financial and commercial operations of the fleet” (Doumerc 2003, p. 157). In 1329, this system became a permanent feature of the muda to Greece, Constantinople, and the Black Sea. In 1331, it was extended to the rest of the western Mediterranean and a decade later to Flanders. The new system allowed a handful of powerful noble families to corner what was by far the most lucrative facet of long-distance trade.44

In addition to sewing up the galley trade, the noble-run Commune directly restricted who could trade on the most lucrative routes. In 1324, just one year after the completion of the Serrata, a law was introduced (the Capitulare Navigantium) that forbade any merchant from shipping wares with a value in excess of the merchant’s assessed wealth. Wealth assessments were used by the Commune to determine taxes and, because only the very wealthy paid taxes, the law excluded the poor from long-distance trade. Indeed, it ensured that only the very richest merchants (those with large assessments) could engage in large-scale long-distance trade. The Officium de Navigantibus was created to enforce the new law. It was initially active for less than a year, but was reinstated in 1331–1338 and again in 1361–1363 (Cessi 1952). Although there were a variety of reasons for the Capitulare Navigantium, restricting trade to nobles and wealthy citizens was an important one (e.g., Hocquet 1997, p. 595). This in turn reduced the economic and political mobility long promoted by Venetian trade. Thus, the Capitulare Navigantium “must have galled many ambitious merchants on the make” (Lane 1973, p. 140).45

To examine the impact of the reorganization of the galley trade in the 1320s and the 1324 Capitulare Navigantium, we look at the characteristics of merchants who used the colleganza before and after 1324 to see (i) whether non-nobles were excluded and (ii) whether, among nobles, usage shifted to those with greater political power (as measured by seat shares in the Great Council). We begin by examining colleganza contracts that have survived for the period 1073–1342. In particular, we examine all contracts that appear in Morozzo della Rocca and Lombardo (1940), Lombardo and Morozzo della Rocca (1953), Tiepolo (1970), and Sebellico (1973). These volumes are collections of all types of commercial contracts, such as dowries, wills, lease agreements, loans, and settlements. We first identify which of these commercial documents are colleganza or settlements of a colleganza. In some volumes, each contract is preceded by an editorial header giving the date, place, and type of contract; however, these headers are often vague or inaccurate, so we reviewed each of the 2,833 documents individually. Identification is tricky and requires a considerable time investment to learn how to distinguish colleganza from other related contracts.46 In all we identified 381 colleganza for the period 1073–1342. Some of these have also been coded by Kedar (1976) and González de Lara (2008): Kedar (1976) examines contracts dated 1240–1323 and González de Lara (2008) examines contracts dated 1073–1261. Although neither codes contracts dated after the Capitulare Navigantium, we have been deeply influenced by their work.

For each colleganza we identify the sedentary and traveling merchants and match their family names to the names of families with seats in the Great Council. This involves standardizing family names using the same procedure described earlier. We have data on Great Council membership and seat shares for 1261–1296. From Raines (2003, appendix 1), we also have Great Council membership (but not seat shares) for 1297–1323. We match the merchants’ family names in the colleganza with the 1261–1296 and 1297–1323 Great Council family names and the 1261–1296 seat shares. For the remainder of this section, we refer to merchants with family members in the Great Council in 1261–1323 as “nobles” and to all others as “commoners.”47

Table I presents the results. Column (1) displays the period. The reader will immediately notice one bit of historical irony—no colleganza have survived for 1262–1309, the period that includes Great Council membership records. This is not crucial because our primary interest is in comparing the pre- and post-1324 periods. The gray-shaded rows are the years in which the Officium de Navigantibus was in operation (1324 and 1331–1338). Recall that the Officium was in charge of enforcing the Capitulare Navigantium.

Column (2) reports the number of colleganza that have survived for each period. Column (3) reports the number of colleganza in which at least one of the merchants was a commoner, that is, a merchant with no family in the Great Council from 1261 onward. Column (4) reports these colleganza as a share of all colleganza in the period. Comparing 1310–1323 with all later periods, there is a sharp drop in commoner participation after the Capitulare Navigantium. During 1310–1323, commoners participated in 27% of all colleganza. After 1324 there is only a single colleganza with commoner participation.48

By 1310, Venice was already deep into the Serrata, so we might expect that an informal process of commoner exclusion may already have been under way. That is, a comparison of the 27% figure for 1310–1323 with the essentially 0% figure for 1324–1342 may understate the full extent of commoner exclusion. It is therefore useful to look further back, to 1241–1261 and even further. Indeed, commoner participation was higher in earlier years, making the 1324 break starker. Commoners were involved in 51% of all colleganza during 1241–1261.49 As far back as 1073–1200, commoners were involved in 42% of all colleganza.50

Column (5) moves the discussion away from commoner participation and to the power of the nobles who participated. In each period we draw up a list of all the merchants involved in a colleganza. We then assign each of these merchants a power score, which is simply his family’s number of seats in the Great Council. (The number of seats is the family’s average number of seats per session during 1261–1296.) We then examine how power scores of the median merchant evolved across periods. Similar results hold for averages. The first observation from column (5) is that the median number of seats is positive, that is, the median merchant had family members in the Great Council. Prior to 1310, the median merchant’s family presence in the Great Council was modest. For example, in 1241–1261, the median family had less than one seat, which signals that this median family alternated in and out of the council. During the Serrata but after the Enlargement (1310–1323), the median merchant’s family held almost three seats. After the Serrata (1325–1338), it jumped even higher, to about five seats. Thus, after the Serrata and, especially after the Capitulare Navigantium, use of the colleganza shifted to more and more powerful families.51

Note that after 1330, there is a very significant drop in the number of extant colleganza. This does not appear to be the result of changes in notarial contracts: we do not see similar trends for other types of contracts. The most convincing explanation has to do with the reorganization of the galley trade. As we discuss next, this led to a shift in financing away from the colleganza and toward financing through family and marriage alliances.

Economic Inequality, Social Stratification, and Resource Reallocation

Overview

The political and economic Serrata had very significant long-run implications for economic inequality, social stratification, and resource reallocation. We turn to the three of these in the following subsections.

Economic Inequality

The capital requirements of the galley trade were huge. A winning bid in the galley auction averaged 793 ducats during 1332–1345. This was only a minor item in the total cost of chartering the galley, which reached 9,200 ducats (equivalent to 33 kg of fine gold) by the late 1400s. In addition to the charter costs, it was necessary to cover salaries and provisions for a crew in excess of 150 men for a period of 5 to 11 months. All of these costs were in turn dwarfed by the cost of the freight, often valued at over 150,000 ducats in the early 1400s.52 In an earlier, pre-Serrata age, these huge up-front fixed costs would have been shared by many merchants, both noble and commoner, and financed with a large number of colleganza. In the post-Serrata age, we initially see broad-based noble participation in the galley trade. However, over the next 150 years an ever-narrower group of nobles came to monopolize the galley trade.

To understand how this happened, one must understand the details of how the state-run galley trade was financed. Each galley in its entirety was auctioned off to a single noble bidder (the patrono), who in turn divided the galley into 24 shares and up to 24 shareholders.53 In the years immediately following the Serrata there was widespread noble participation in the galley trade. This was necessary because not even the richest families could afford the high up-front capital costs of a successful bid.

The mid-1300s were a difficult time for trade, with the plague of 1348 and ongoing wars with Genoa until 1380. After 1380, however, Venice began to recover and with this recovery a slow process of concentration in the galley trade began. At the start of the recovery, participation was still widespread: two thirds of noble families participated in the galley trade and more than a a third provided patroni (Doumerc and Stöckly 1995, p. 143). By the mid-1400s, evidence of increasing concentration in the galley trade was inescapable. In Doumerc and Stöckly’s (1995, pp. 140–142) analysis of 121 galleys during 1445–1452, the patrono held the majority of shares, either alone or with his brothers and sons, in 60% of galleys. On average, the patrono’s family held 56% of the shares. More and more often the patrono was from a particularly prominent family.

To become a majority shareholder in a galley, a noble typically had to give up the advantages of risk diversification and concentrate his investment in that galley. During 1445–1452, 85% of shareholders were invested in a single galley (Doumerc and Stöckly 1995, p. 146). By 1500, it was common for a single family to hold all of the shares in a galley. One even begins to see instances where all the galleys in a muda (convoy) are controlled by a family or small group of families. For instance, the brothers Alvise, Andrea, and Pietro Marcello held all 24 shares in a galley of the muda to Trafego in 1496. They raised their stake with 12, and then 18, and then 23 shares in a second galley in 1497, 1498, and 1499, and finally held all 48 shares in two of the three galleys of the muda to Trafego in 1500 (Doumerc and Stöckly 1995, p. 147; Judde de Larivière 2008, p. 181).

The greatest advantage of cartelizing a muda came from price fixing. Michiel da Lezze, son-in-law of Pietro Marcello, left detailed evidence of this practice in his business correspondence (Braudel and Tenenti 1966, p. 62). In 1506 he instructed his son Luca, patrono of a galley of the muda to the Barbarie Coast, to collude with the other patroni as monopsony buyers to drive down the price of wool in Valencia. Upon returning home, they colluded again as monopolists to drive up the sale price in Venice. These and other anticompetitive practices begin to appear frequently in court cases from 1450 on. “The abuses are more and more frequent as financial concentration increases” (Doumerc and Stöckly 1995, p. 147, our translation).

Controlling an entire muda required vast financial resources, and during the course of the 1400s a uniquely un-Venetian solution emerged. Family members, typically brothers, raised capital within a family. Because even this was rarely enough to control one or several galleys, marriage alliances were established with other powerful families and additional capital was raised within the alliance. This in part explains the decline of the colleganza documented above. It is a step backward from impersonal relationships to kin-based relationships as the basis for Venice’s long-distance trade. It is also a step backward from the era of pre-Serrata economic mobility. In its place a period of spectacular inequality at the top end of the income distribution was ushered in.

The use of marriage alliances had a profound effect on financing and hence on concentration in the galley trade. The 46 galleys sent in the muda to the Levant between 1519 and 1528 had an average of just two shareholders, despite a cargo value worth between 150,000 and 200,000 ducats per galley (Doumerc and Stöckly 1995, p. 152). Furthermore, the lists of shareholders after 1500 are dominated by the Contarini, Garzoni, Marcello, Loredan, Pisani, Priuli, Michiel, Morosini, and a very small handful of other rich families. During the period 1495–1529, 30 individuals from just 17 noble families owned 38% of all shares in the galleys of the different muda (Judde de Larivière 2008, table 8, p. 140). Over the same period, the families of the shareholders were linked by marriage in almost every single galley (Judde de Larivière 2008, p. 144).

The problems of monopolization—both the anticompetitive costs and the implications for extreme inequality—were decried by contemporary chroniclers such as Sanudo and members of the Great Council. Ideally, we would like to track the extreme inequality associated with the rise of this ultra-rich elite, especially after the post-1380 Venetian expansion. One certainly sees it visually in the ornate palazzos that began lining the Grand Canal in this period (Goy 1992, p. 10). Unfortunately, there are no systematic data that would allow us to track economic inequality.54 Nevertheless, we have been able to exploit a source that has not previously been systematically examined: records of Venetian noble marriages.55 Since these marriages were intimately connected with cartelization, as we have seen, this will give us a systematic portrait of post-Serrata Venetian economic polarization.