“Responsible” dog ownership had to be enforced through a canine tax.

By Dr. Iosif Botetzagias

Historian of Environmental Politics and Sociology

In this article, I discuss attitudes towards “roaming dogs” in late nineteenth-century Athens, Greece. As indicated by researchers including Frederick Brown, Philip Howell, Chris Pearson, Neil Pemberton, and Michael Worboys, such a study is key to assessing the living reality of (and feelings towards) canines as well as to understanding urban developments.

On 12 March 1886, following rabies incidents in neighboring regions, the pro-government newspaper Nea Efimeris reported that the Athens municipal police issued a decree stipulating that, starting 15 March, any dogs found “not leashed by their masters or unmuzzled … roaming in the streets” would be detained and, if not reclaimed, killed. Yet, on 16 March, an unsigned article argued that, with dogs swarming the streets and the threat of rabies omnipresent, this was not enough: “In such circumstances, which filled the streets with dirty dogs, curs and mutts, the police must take also some secret measures—they know what we mean.” The author had to have been none other than Nea Efimeris’s editor, Ioannis Kabouroglou, and the “secret measures” was poisonous baiting (fola), a customary practice for curbing stray dog numbers, often administered by policemen themselves. Thus, on 18 March 1886, Akropolis newspaper reported that “wherever one turned his eye he could see dead dogs’ bodies … poisoned with strychnine … thrown [by the police].”

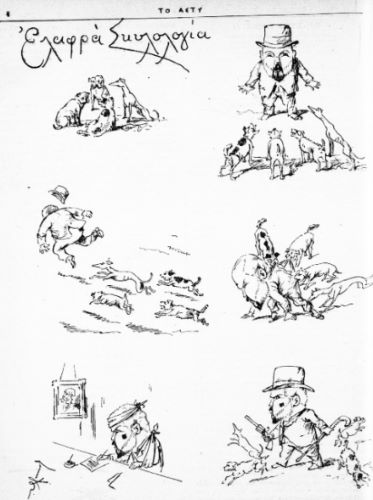

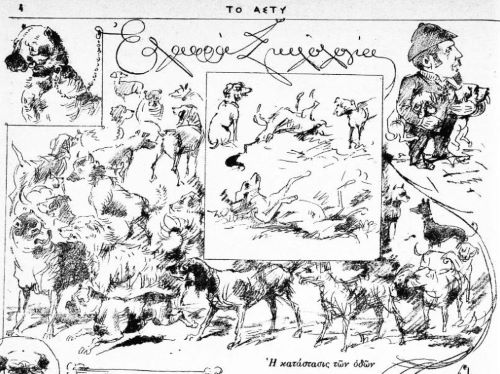

This age-old practice provoked an unprecedented reaction. The progressive Akropolis attributed the onslaught to “the comments of one of our colleagues suffering from kynophobia … and the ‘secret measures’ he allured to.” On 23 March 1886, the weekly satirical paper To Asty featured a caricature showing a dog muzzling the minister of the interior and police supervisor, Nikolaos Papamichalopoulos, and commented that the police did not have to use arsenic: “It will suffice to throw to the dogs some sheets of Nea Efimeris’s issues, which—if consumed—will have the same fatal effect.” The country’s medical council unanimously opined that the fola practice should stop since it risked poisoning other animals—as well as humans. And when, on 19 March 1886, the police (temporarily) complied, Nea Efimeris fumed: “[The Medical Council’s] claims are rather excessive, and it should be concerned about people rather than dogs. When the whole Medical Council cannot save a single man bitten by a rabid dog, its protection of the dogs is very curious!”

Nevertheless, both sides agreed that the root cause of the problem was the dog owners’ indifference; thus “responsible” dog ownership had to be enforced through a canine tax. That way, the dogs’ masters would then take all measures necessary to protect their prized property from being poisoned in the street. “We are unorderly and insubordinate to what is set and ordered for our safety, and we do not want to pay a heavy tax for our dog loving, as it is the case elsewhere,” maintained Nea Efimeris on 16 March 1886. Meanwhile, on 20 March, an anonymous letter to the editor called for a tax on dogs to finance the treatment of rabies victims and for the police to turn a deaf ear to the protests of those who “have no wish to respect the laws, and … do not consider the dangers that the negligent upkeep of their dogs entail for their fellow citizens.” Akropolis, despite its critical stance, also noted “a good result follow[ing] yesterday’s dog ruin”—private dogs were now muzzled and on leash around Athens. In a similar vein, the comical “Complaint of the injured party to the Greek government,” appearing in To Asty and allegedly “commissioned by 250 dogs,” “welcome[d] the substitution of all these barbaric measures (poisoning, muzzling, being chained) by a tax,” which of course one would only pay for a “prized dog.”

“Is [ours] a society of humans or of dogs?,” Nea Efimeris asked in spring 1886. All involved seemed to agree that if nineteenth-century Athens was to become the former, then dogs had to be turned into valued, and paid for, personal assets. “[T]he masterless, the incompetent and the depraved w[ould] be left on the lurch,” as the dogs’ “complaint” argued in its closing lines. Or, as the anti-monarchy satirical newspaper Rabagas put it on 20 March 1886, “you [i.e., dogs] want to be insured by [the Athens police] life-insurance company? You ought to have a master. You are not allowed to be free. Freedom will bring you death!”

A tax on dogs was finally introduced in Greece in summer 1899, only to be revoked in early 1902. Speaking before Parliament, the minister of finance, Anargiros Simopoulos, claimed that although the dog tax contributed to “reducing the number of useless dogs as well as curbing rabies,” it has also “raised considerable complaints” and failed to “secure any worthwhile revenue for the Treasury”; thus, “the further upkeep of such a tax cannot be justified” (SKRIP, 18 February 1902). Throughout the twentieth century, roaming dogs continued to be collected and—when not reclaimed—(humanly) killed. It was only during the 2000s that Greece outlawed the killing of roaming or stray dogs and introduced the obligatory registering of all canines. In stark contrast to what is the case in western Europe, current Greek legislation recognizes a dog’s “right” to be owner-less and roam-free in an urban environment, while safeguarding such a dog’s right to life, with harsh penalties against transgressors. Thus, Greek stray dogs now have a set of rights that amount to “citizenship,” in the words of Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka. Over a century after Kabouroglou’s rhetorical question, the answer is: ours is a society of humans and of dogs.

Originally published by Arcadia: Explorations in Environmental History, 24 (Autumn 2023), under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.