The young radicals of Narodnya Volya were the heroes of Lenin’s youth.

By Dr. Neil Faulkner

Late Research Fellow

University of Bristol

Introduction

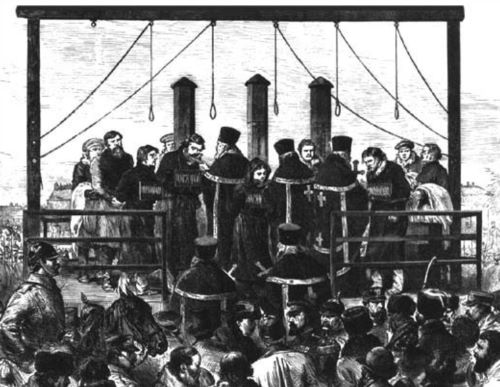

Early on the morning of 5 May 1887, a small steamer delivered five students, shackled in irons, to the Schlusselburg Fortress on the River Neva, a short distance from St Petersburg. They were held in separate cells, small and whitewashed, with stone floors and iron doors, for three days. Then, on 8 May, they were woken in the early hours and led into the prison courtyard, where three wooden scaffolds had been erected. They were hanged in two batches. Two of them, before they died, cried out the name of their party: ‘Long live Narodnya Volya!’

They had been condemned to death for membership of a ‘criminal society attempting to overturn the existing state and social order by means of violent revolution’. They had, the prosecutors explained, organised a ‘secret circle for terrorist activity’ and were planning to assassinate Tsar Alexander III.

One of the five was called Alexander Ulyanov.1 The 20-year-old son of a school inspector and minor notable, he had been brought up in Simbirsk, a dull provincial town on the River Volga. His younger brother was still attending high school there. His name was Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. The world would come to know him as ‘Lenin’.

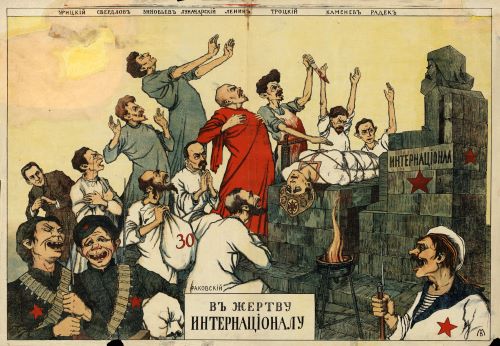

The man who became the leader of the Bolsheviks is incomprehensible without his Narodnik background. The young radicals of Narodnya Volya were the heroes of Lenin’s youth. Though he never spoke of his brother in public, there can be little doubt that Alexander’s martyrdom affected him deeply. He read and re-read What is to be Done?, and his private photo albums contained several pictures of Chernyshevsky. His wife and comrade, Nadezhda Krupskaya, tells us that he always held ‘the old revolutionaries of the Narodnya Volya in great respect’.2 At the end of his own What is to be Done? (1902) – so-named, of course, in honour of Chernyshevsky – he wrote of Russia’s new generation of revolutionaries as follows:

Nearly all of them in their early youth enthusiastically worshipped the terrorist heroes. It was a great wrench to abandon the captivating impressions of these heroic traditions, and it was accompanied by the breaking off of personal relationships with people who were determined to remain loyal to Narodnya Volya and for whom the young Social Democrats had profound respect.3

This was autobiography: this was the difficult journey taken by the man whose brother had swung in the noose of a Tsarist hangman for his allegiance to Narodnya Volya.

The Narodniks failed because they attempted to substitute the individual terrorism of revolutionaries for the collective action of the masses. Lenin and his followers were inspired by the romantic heroism of the Narodniks, but appalled by the futility and waste. They understood – even admired – the impatience and idealism, but at the same time knew that history could not be forced. The essence of Lenin’s politics – worked out between 1888, when he first read Marx, and 1902, when he wrote What is to be Done? – was to think of revolution as a process for which an engine had to be constructed. His design had four main parts. These were: a vision of the world transformed by revolutionary action; an underground activist network to turn this vision into a framework political organisation; the growing of this organisation into a mass social movement through recruitment of the most militant people in every industrial centre; and the eventual role of this essentially proletarian-urban movement in detonating a country-wide insurrection of the Russian Narod. Let us consider this ‘blueprint’ for revolution in more detail.

The Concept of Revolution

Marxism can be defined as the theory and practice of international working-class revolution. When the young revolutionaries Karl Marx and Frederick Engels were first working out their ideas in the early 1840s, they confronted what appeared to be a historical riddle. The steady rise in the productivity of human labour throughout history meant increasing capacity to abolish want. Yet a minority continued to enjoy grotesque wealth while millions lived in poverty. The riddle was: who might so reorder the world that human labour served human need?

Their answer to this question was the new working class – or proletariat – being created by the Industrial Revolution. This was partly because it was an exploited class, one with no vested interest in the system, with, as they put it, ‘nothing to lose but its chains’. But this had been true of the slaves of ancient Rome and the serfs of medieval Europe. A second factor was decisive. The workers – unlike slaves or peasants – could not emancipate themselves through individual appropriation of private property. They were part of a complex international division of labour, such that only collective control over the means of production, distribution, and exchange could provide a credible alternative to capitalism. The village might march on the mansion, evict the landlord, and divide up the estate into small plots. The situation of the workers was quite different. Concentrated in factories and cities, the workers were bound to act collectively. And, since they could not partition a textile mill, railway line, or telegraph network, were they to take power as a class, they would be obliged to rule collectively. The proletariat was therefore the first class in history with a general interest in the emancipation of humanity as a whole.

The 1848 Revolutions – which swept across Europe that year, with armed uprisings in Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Prague, Rome, and a dozen other major cities – led Marx and Engels to another radical conclusion: that the proletariat was the only class capable of any sort of determined revolutionary action. During the armed uprisings, the liberal bourgeoisie, fearful of social upheaval, had stood paralysed as the cannon of counter-revolution cleared the barricade-fighters from the streets. ‘In the best of cases,’ Engels later wrote, ‘the bourgeoisie is an unheroic class. Even its most brilliant victories – in England in the 17th century or in France in the 18th – had not been won by it itself, but had been won for it by the plebeian masses of people.’ This was quite so. Without action from below by revolutionary crowds in London, and later by the soldiers of the New Model Army, the English Revolution would have stalled. Equally, without repeat insurrections by the Parisian sansculottes – in 1789, 1792, and 1793 – the Jacobins, the most resolute of the French bourgeois revolutionaries, would never have come to power. But the German bourgeoisie of 1848 seemed to have plumbed new depths of ‘stupidity and cowardice’, and the searing experience of its spinelessness, culminating in a comprehensive defeat for democracy, had compelled Marx and Engels to reconfigure their conception of what they – like Trotsky much later – called ‘permanent revolution’.4

This represented an extraordinary shift of perspective and strategy. Marx was, in effect, announcing that the bourgeois revolution was over, that the struggle for democratic reform was now inextricably bound up with that for social reform, and that henceforward the sole agent of revolution was the (at that time still embryonic) industrial proletariat. He, and to a greater extent Engels, later retreated from the radicalism of this conception (of 1849), and there seems to be little trace of it in late nineteenth-century Marxism. The Russian Social Democrats were therefore confused about the nature of their own imminent revolution – confused to the point of bitter controversy.

Lenin’s position (until 1917) was that of the mainstream – but with a Russian twist. He argued that revolutionary action by the proletariat and peasantry was necessary to accomplish the tasks of the ‘bourgeois revolution’ – the overthrow of the autocracy, the establishment of a democratic republic, a redistribution of land to the peasants, and an eight-hour day in the factories. The autocracy would not relinquish power voluntarily, therefore revolution was necessary. But the liberal bourgeoisie was bound to betray the revolution, so that ‘the only force capable of gaining a decisive victory over Tsarism is the people, i.e. the proletariat and the peasantry … The revolution’s decisive victory over Tsarism means the establishment of the revolutionary-democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry.’5

What the Marxist philosopher Georg Lukács called ‘the actuality of the revolution’ was at the very core of Lenin’s politics. He was, on his Russian side, a descendant of the Decembrists and Narodniks, and on his European, of Marx and Engels. In him, the romantic tradition of revolutionary heroes battling a police state was allied to the theory and practice of international working-class revolution. More precisely – and true to Marx’s axiom that ‘the emancipation of the working class will be the act of the working class’ – the two conceptions fused in Leninism, such that the heroic leader of the people became the revolutionary proletariat itself.6

Lenin’s touchstone became the revolutionary programme adopted by the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party at its Second Congress in 1903. Written by Plekhanov and effectively the party’s founding statement, Lenin, for the rest of his political career, would insist upon adherence to it – in opposition to backsliders and renegades – as the true measure of socialist commitment. It was unequivocal:

the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party takes as its most immediate political task the overthrow of the Tsarist autocracy and its replacement by a democratic republic … In striving to achieve its immediate aims, the RSDLP supports every oppositional and revolutionary movement directed against the social and political order prevailing in Russia … the RSDLP is firmly convinced that complete, consistent, and lasting realisation of … [radical change] … is attainable only through the overthrow of the autocracy and the convocation of a constituent assembly, freely elected by the entire people.7

The Revolutionary Underground

Radical ideas, if they are to become an historical force, must be turned into political organisation. A vision of the world transformed is pie in the sky without a revolutionary party. On the other hand, there is no blueprint for revolutionary parties. History reveals many different kinds. It also shows them forming, growing, and changing as organic parts of mass movements. The Levellers, the Chartists, the Jacobins, and the Communards can all be regarded as alternative forms of revolutionary party. The Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party was yet another kind. What all of these have in common is a) that they were mass parties rooted in social movements, and b) that they developed organically over time. The Bolshevik leader Grigori Zinoviev explained that a party

is a living organism connected by millions of threads with the class from which it emerges. A party takes shape over years and even decades … the living dialectical formation of a party is a very complex, lengthy, and difficult process. It is born amid sharp pangs, and it is subject to perpetual crystallisations, regroupings, splits, and trials in the heat of struggle before it finally takes shape as a party of the proletariat…8

A revolutionary party, then, is not a thing that springs ready-made into existence – like Athena from the head of Zeus at the stroke of history’s hammer – but is something that evolves continuously in an organic relationship with the class movement of which it is part. The revolutionary party is never in a state of being, only ever in a state of becoming.9

So it was with the Bolsheviks. The ‘prehistory’ of Russian Social Democracy can be traced back to the establishment of a ‘Chaikovist’ group in St Petersburg in 1870, a ‘South Russian Workers’ League’ in Odessa in 1875, and a ‘North Russian Workers’ League’ in St Petersburg in 1878. All these organisations, however, were tiny, short-lived, and intellectually inchoate. More substantial – and explicitly Marxist – was the ‘Emancipation of Labour Group’ formed by Georgi Plekhanov in St Petersburg in 1883, after he and a handful of other intellectuals had made the break with Narodnik populism and committed themselves to building a proletarian party.

But the impact of Russia’s socialist pioneers was minimal. Though the state-driven industrialisation programme was gathering steam, the working class remained relatively small. There had been a miniature strike wave in the late 1870s, but severe repression following the assassination of the Tsar in 1881 smothered both incipient labour militancy and embryonic socialist organisation for a decade. Russian Social Democrats could be numbered in the tens, most of them exiles. Plekhanov remained their standard-bearer. ‘The Russian revolution will either triumph as a revolution of the working class,’ he declared at the First Congress of the Second International in 1889, ‘or it will not triumph at all.’10

There are desert plants that lie dormant for years only to erupt suddenly into life when finally it rains. Plekhanov’s big idea was of this kind. It was a seed hidden in the social depths awaiting an eruption of mass struggle that would allow it to burst forth. It was a long time coming, but then, in the mid 1890s, Russia’s new industrial districts were rocked by strikes far bigger than those of the late 1870s. A new generation of revolutionary intellectuals – including a young Lenin, who had arrived in the capital from provincial Simbirsk two years previously – were active supporters of the strikes. In 1895, Lenin and others founded the St Petersburg League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class. The movement peaked in May 1896 with a three-week strike by 30,000 St Petersburg textile workers in which the League of Struggle played a leading organisational role. Russian Social Democracy thus became a small mass movement. Its committed activists were now to be numbered in the hundreds.

But the movement subsided. Lenin and five other members of the St Petersburg League had been arrested in December 1895 and sentenced to terms of exile in Siberia. When the remnants of several groups met in Minsk in March 1898, this ‘First Congress’ of Russian Social Democrats comprised just nine delegates. No party programme was adopted, and eight of the delegates, including two of the three newly elected Central Committee members, were arrested within days.11

Lenin, meantime, had three years of exile to reflect on his experience of the class struggle and the socialist underground. When he returned to active politics in 1899, he had a fully worked out strategy for building a revolutionary party in Russia. Much of the debate about ‘Leninism’ hinges on interpretations of Lenin’s theory and practice in this crucial period, between 1899 and 1903, when ‘Bolshevism’ emerged as a distinct current within Russian Social Democracy.

Despite much ill-informed commentary to the contrary – by both enthusiasts and detractors – Lenin’s Bolshevik Party was never a ‘democratic-centralist’ sect. A political sect can be defined as a small organisation run by a self-appointed ‘vanguard’ that seeks to insert itself into a mass movement in order to grow parasitically like a tic. A ‘democratic-centralist’ organisation is one where power is concentrated in the hands of a (largely) self-perpetuating leadership, or even in the hands of a single cult-like guru. Small organisations of this kind exist in all periods. Mass revolutionary parties, on other hand, are never like this. The reason is simple: revolution ‘from below’ – that is, revolution where the emancipation of the masses is the act of the masses themselves – means an explosion of democracy. Here is how Trotsky described it in his History of the Russian Revolution:

The most indubitable feature of a revolution is the direct interference of the masses in historic events … at those crucial moments when the old order becomes no longer endurable to the masses, they break over the barriers excluding them from the political arena, sweep aside their traditional representatives, and create by their own interference the initial groundwork for a new regime … This history of a revolution is for us first of all a history of the forcible entrance of the masses into the realm of rulership over their own destiny.12

The ideal to which Lenin and the Bolsheviks aspired was therefore an open, mass, democratic party capable of giving effective expression to the revolutionary energy of the Russian working class. Their model was the German Social Democratic Party (SPD). The largest working-class organisation in the world, and the dominant force in the Second International (a confederation of European socialist parties), by 1912 the SPD had a million members, was publishing 90 daily papers, and ran a women’s section, a youth section, various trade unions and co-ops, and numerous sports clubs and cultural societies. In that year, it made a dramatic electoral breakthrough, winning one in three votes, becoming, with 110 seats, the largest party in the Reichstag, the German parliament. In the space of a generation, it had been transformed from a small outlawed minority into a mass social movement and electoral machine.13 The SPD’s theoretical foundation-stone was Karl Kautsky’s Erfurt Programme (1892), a book-length treatise on the perspective and strategy of the up-and-coming German workers’ party. That Lenin translated it into Russian in 1894 tells us everything we need to know about his political debt to Kautsky and the SPD.14 That this debt was huge is confirmed by the testimony of other Bolsheviks, all of whom, without apparent exception, regarded the SPD as a model socialist party.15

The problem in Russia was the police. How do you build a mass democratic party in a police state? To organise openly was impossible, and without open organisation you could neither make democratic decisions nor hold democratic elections. Indeed, the looser the network, the more vulnerable it was to penetration by the police. The more people you had attending a meeting, especially when many were new and inexperienced in underground work, the greater the risk of discovery and arrests. How, in these circumstances, could the party make democratic decisions? How could the leadership be democratically chosen? The simple fact was that democracy and police repression were polar opposites. Two questions therefore imposed themselves on Russia’s Social Democratic underground: a) how best to build socialist organisation in Tsarist Russia; and b) how best to uphold the principles and programme of the party.

‘The closer the end of our exile drew in sight,’ wrote Krupskaya, Lenin’s partner,

the more did Vladimir Ilyich think about the work facing us. The news from Russia was scanty. ‘Economism’ was gaining ground there, and there was no party to speak of. We had no printing plants in Russia … Party work was completely disorganised, and constant arrests made any continuity impossible.16

‘Economism’ was a reformist argument inside Russian Social Democracy to the effect that the workers should concern themselves with the ‘economic’ struggle for improved conditions and leave the ‘political’ struggle for democracy to the liberals. It reflected a mechanical view of the coming Russian revolution as ‘bourgeois’ rather than ‘proletarian’.17 That this idea could gain so much traction among Russian socialists was, for Lenin, a symptom of the organisational and ideological disintegration of the party.

Lenin’s plan for the reconstruction of Social Democracy was two-fold. First, he proposed the publication of an all-Russian socialist newspaper. This would be produced abroad, smuggled into Russia, and then distributed to the underground groups across the country. A coherent set of revolutionary-socialist ideas disseminated in this way would cement together the party’s activist network and help it recruit new members. Moreover, the very process of illegal distribution would itself create and sustain the network. ‘A paper is what we need above all’, he wrote.

Without it we cannot systematically carry on that extensive and theoretically sound propaganda and agitation which is the principal and constant duty of the Social Democrats … Our movement, intellectually as well as practically (organisationally), suffers most of all from being scattered, from the fact that the vast majority of Social Democrats are almost entirely immersed in local work, which narrows their point-of-view, limits their activities, and affects their conspiratorial skill and training … The Russian working class … betrays a constant desire for political knowledge – they demand illegal literature, not only during periods of unusual unrest, but at all times.

Political education was one function of the revolutionary paper. There was another. He continued:

the role of the paper is not confined solely to the spreading of ideas, to political education, and to procuring allies. A paper is not merely a collective propagandist and collective agitator; it is also a collective organiser. In that respect, it can be compared to the scaffolding erected around a building in construction … With the aid of, and around, a paper, there will automatically develop an organisation … The mere technical problem of procuring a regular supply of material for the newspaper and its regular distribution will make it necessary to create a network of agents of a united party … This network of agents will form the skeleton of the organisation we need.18

The second part of Lenin’s plan was to tighten party organisation to make it more impervious to police penetration. This is perhaps the most widely misconstrued aspect of Lenin’s work. An immediate practical response to the problem posed by the Tsarist police has been elevated into either a universal principle of revolutionary organisation (in the case of sectarians) or into a grand strategy for the construction of a totalitarian dictatorship (among right-wing commentators). Here is what Lenin actually proposed:

The leadership of the movement should be entrusted to the smallest possible number of the most homogeneous possible groups of professional revolutionaries with great practical experience. Participation in the movement would extend to the greatest possible number of the most diverse and heterogeneous groups of the most varied sections of the proletariat (and other classes of the people) … We must centralise the leadership of the movement. We must also … as far as possible decentralise responsibility to the party on the part of its individual members, of every participant in its work, and of every circle belonging to or associated with the party. This decentralisation is an essential prerequisite of revolutionary centralisation and an essential corrective to it.19

This can be summarised as: keep the core cells of the party centralised and closed (to protect them from the police); but encourage the highest possible level of initiative and activity on the part of the wider mass movement within which the party is embedded.

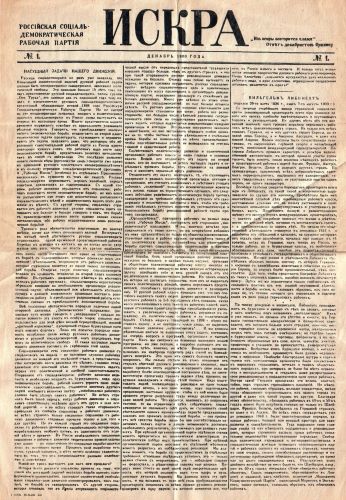

The first all-Russian socialist newspaper – Iskra (‘The Spark’) – was launched in December 1900. Over the next three years, while Lenin was on the editorial board (he was destined to lose control of his own creation), a total of 51 issues appeared.20 The establishment of Iskra was uncontroversial, but the other part of Lenin’s plan – to make the party more police-resistant – proved far more problematic: it was, in fact, the origin of a factional dispute that would divide the party for more than a decade.

It blew up – unexpectedly – at the Second Congress of the RSDLP (the first proper conference), held in Brussels and London in July‒August 1903. About 60 people attended (though not all with voting rights) and virtually all the major industrial cities and regions were represented.21 Lenin worked hard in preparing the conference, hoping to match the achievement of founding Iskra with the creation of ‘a united solid party, merging into one all the detached groups … a party in which there would be no artificial barriers’ (Krupskaya).22 He set out his vision in advance in a long pamphlet destined to become one of his most famous publications: What is to be Done? It ends with this rallying cry to all the revolutionary forces of Russia:

If we genuinely succeed in getting all or a significant majority of local committees, local groups, and circles actively to take up the common work, we would in short order be able to have a weekly newspaper, regularly distributed in tens of thousands of copies throughout Russia. This newspaper would be a small part of a huge bellows that blows up each flame of class struggle and popular indignation into a common fire. Around this task … an army of experienced fighters would systematically be recruited and trained. Among the ladders and scaffolding of this common organisational construction would soon rise up Social Democratic Zheliabovs from among our revolutionaries, Russian Bebels from our workers, who would be pushed forward and then take their place at the head of a mobilised army and would raise up the whole Narod to settle accounts with the shame and curse of Russia.23

This passage encapsulates the fusion of theoretical clarity, practical measures, and revolutionary romanticism that was the essence of Lenin’s politics – in contrast to the desiccated conceptions of both sectarians and reactionaries. The newspaper will create and bind together an underground network. The network will combine the heroism of Narodniks (like Zheliabov) with the politics of Social Democrats (like the German SPD leader Bebel). It will fan into flame a movement of the whole people (the Narod: workers and peasants) powerful enough to destroy the Tsarist regime.24

For some, the vision was an inspirational dream. For others, it was a nightmare. Though issues became tangled and allegiances shifted, in the succession of rows that divided the Second Congress can be detected a fundamental difference between those who sought compromises with others and those whose aim was proletarian revolution.

The most significant argument arose over a seemingly minor issue: the definition of a party member. Lenin proposed that the statutes should define a member as one ‘who recognises the party’s programme and supports it by material means and by personal participation in one of the party organisations’. Martov proposed deleting the final phrase and replacing it with ‘and by regular personal association under the direction of one of the party organisations’.25 The issue at stake was simple: was the party to be formed only of the activist vanguard, or was it to include anyone loosely ‘associated’ with the party?

There was nothing elitist about Lenin’s conception: anyone could choose to become a party activist. His point was that only those who committed themselves in this way should be empowered to make decisions. The risk otherwise was that the politics of the party would be diluted by a lukewarm swamp of passive ‘members’. At root, Lenin argued, Martov was confusing party and class:

the party must be only the vanguard, the leader of the vast masses of the working class, the whole (or nearly the whole) of which works ‘under the control and direction’ of the party organisations, but the whole of which does not and should not belong to a ‘party’ … when our activities have to be confined to limited, secret circles and even to private meetings, it is extremely difficult, almost impossible in fact, for us to distinguish those who only talk from those who do the work … It would be better if ten who do work should not call themselves party members … than that one who only talks should have the right and opportunity to be a party member.26

Lenin was right. The revolutionaries were a minority swimming against the current. Confronting them was the whole power of official society, which, by force and by fraud, was deployed to contain the class struggle. When the workers came onto the streets, they faced force – the batons and bullets of the police. The rest of the time, they were sold a fraud – that God had ordained the social order, that the Tsar was their ‘Little Father’, that the Jews were the enemy. Most workers, in consequence, had a ‘mixed consciousness’. Because they were victims of the system, they were open to the arguments of revolutionaries, especially in moments when they gained confidence through collective struggle. But because they were also ground down by the system, they were rarely wholly free of what Marx called ‘the muck of ages’ – the piety, deference, and racism that conspire to keep people in their place by their own decision.

If this were not the case – if the working class was instinctively and spontaneously revolutionary – there would be no need for a party. Martov’s conception, where the party is dissolved into the mass, would then be the right one. But in reality class consciousness is contested and contradictory. A battle of ideas rages across society, with socialists on one side and the propagandists of the system on the other. Conscious-ness is therefore uneven across the working class. Because of this, the party must comprise a vanguard of worker-activists who have broken decisively with the old order, who reject all its reactionary arguments, who embrace the vision of a world transformed, who come, individually and collectively, to embody ‘the actuality of the revolution’. Only a party so formed would be capable of resisting the pull to the right – towards what was called, in the political discourse of the time, ‘conciliationism’ or ‘liquidationism’ – and instead constitute a solid pole of attraction for the accumulation of revolutionary forces.

A line was drawn at the Second Congress between reformists, henceforward known as ‘Mensheviks’ (meaning ‘supporters of the minority’), and revolutionaries, henceforward ‘Bolsheviks’ (‘supporters of the majority’). Lenin lost some votes, won others, and emerged in control of the party leadership. But he later found himself displaced as allegiances shifted again inside the small groups of Russian political exiles whose self-appointed task it was to sustain the party infrastructure and supply it with literature. He fretted over the divisions, doubted their significance, made overtures to repair relationships. It seemed absurd, with so much at stake, with such a sound plan in place, that the party should be wrecked by faction.

The divisions, however, were real. Time would show this. The mass of RSDLP members favoured unity. The workers were intolerant of squabbles among exiled party intellectuals, who appeared self-indulgent and irresponsible to those engaged in day-to-day struggle against the bosses and the police. Partly because of this, relations between the two factions see-sawed between split and semi-unity until January 1912, when, at a small party congress in Prague convened by the Bolsheviks but boycotted by the Mensheviks, Lenin’s followers assumed authority over the RSDLP.27 What made this event decisive was that the Bolsheviks now enjoyed an overwhelming majority among the activists of the revolution-ary underground inside Russia, and that the working-class movement in which they were embedded was entering upon a new phase of mass struggle.

So the division in the RSDLP was not a sudden event engineered by a dogmatic ‘splitter’ in 1903; it was a decade- long process in which a powerful instinct for unity was eventually overwhelmed by intractable differences. Nor was the substantive issue – as the common caricature would have it – Bolshevik ‘centralism’ versus Menshevik ‘democracy’. As soon as police repression was lifted and open party-building became possible – as during the 1905 Revolution – Lenin starting denouncing the centralism and conservatism of Social Democratic activists. ‘We need young forces’, he wrote in February 1905:

I am for shooting on the spot anyone who presumes to say that there are no people to be had. The people in Russia are legion; all we have to do is to recruit young people more widely and boldly … without fearing them. This is a time of war. The youth – students, and still more so the young workers – will decide the issue of the struggle. Get rid of all the old habits of immobility, of respect for rank, and so on. Form hundreds of [party] circles … from among the youth and encourage them to work full blast … Allow every sub-committee to write and publish leaflets without any red tape (there is no harm if they do make a mistake) … Do not fear their lack of training, do not tremble at their inexperience and lack of development … Only you must be sure to organise, organise, and organise hundreds of circles, completely pushing into the background the customary, well-meant committee (hierarchic) stupidities.28

Lenin’s problem in 1905 was the inherent conservatism of all human organisation. Without a degree of routine and continuity, no stable political party can exist. But when the tide turns, the party must go with it or be left washed up on the beach. The ‘professional revolutionaries’ of 1903 – the Comitetchiki (committee-people) – became barriers to the creation of a mass democratic party in 1905. They feared ‘dilution’ of the party. Lenin railed against them, demanding mass recruitment of young workers and the replacement of intellectuals by workers on party bodies. ‘The inertness of the committee-people has to be overcome’, he proclaimed. ‘Workers have the class instinct, and, given some political experience, they pretty soon become staunch Social Democrats. I should be strongly in favour of having eight workers to every two intellectuals on our committees.’29

What is to be Done? and the 1903 split have become fetishised – transformed into the holy text and founding ritual of a mythological ‘party of a new type’. The truth is that Lenin was ‘a man of the people’ to his inner core; that all his political instincts were deeply democratic; and that his politics were rooted in a profound belief in the transformative power of mass working-class action. Everything else was secondary: a matter of the strategy and tactics necessary to unleash the torrential force of a democracy shackled by a police state. As Krupskaya explained it, reflecting on Lenin’s early years as a propagandist and agitator among the St Petersburg workers:

Vladimir Ilyich had implicit faith in the proletariat’s class instinct, its creative powers, and historic mission. This faith had not come suddenly to Vladimir Ilyich, but had been hammered out during the years when he had studied and pondered Marx’s theory of the class struggle, when he had studied Russian realities, and learnt, in fighting the ideas of the old revolutionaries [the Narodniks], to offset the heroism of the solitary fighter by the strength and heroism of the class struggle. It was not just blind faith in an unknown force, but a deep-rooted belief in the strength of the proletariat and its tremendous role in the cause of working-class emancipation, a belief founded on a profound knowledge and thorough study of the facts of life. His work among the St Petersburg proletariat had helped to identify this faith in the power of the working class with real live people.30

The Activist Vanguard

Osip Piatnitsky was an active socialist for more than 40 years. A Polish Jew and apprentice tailor, he was introduced to Social Democratic politics by his two older brothers and his workmates at the age of 14. He was soon active in the illegal tailors’ union, in the Bund, the Jewish socialist party affiliated to the RSDLP, and in a clandestine political discussion circle (the boundaries between union, party, and circle were highly porous in the underground movement). Experience of strikes and street clashes with Cossacks and police hardened his politics. In the winter of 1900/1, he broke with the Bund in opposition to its Jewish separatism, becoming an ‘Iskra-ist’, a member of the group that would soon evolve into the Bolsheviks. Despite awesome personal sacrifice – periods of unemployment, poverty, homelessness, and hunger; periods of imprisonment and Siberian exile – his will remained unbroken.31 He was an archetypal ‘worker-Bolshevik’, a ‘professional revolutionary’ in the manner of Lenin’s What is to be Done?, the kind who, in Trotsky’s description, ‘dedicates himself completely to the labour movement under conditions of illegality and forced conspiracy’.32 A rare survivor from the earliest years, he was, like so many of the Old Bolsheviks, eventually murdered by Stalin’s police (in 1938).

How did the revolutionary underground to which Piatnitsky belonged operate? Leaflets might be printed on a secret press, reproduced on a hectograph machine, or even copied out by hand. They would then be distributed in bundles at a clandestine meeting and each activist allocated one or more streets for delivery. Copies of revolutionary pamphlets and newspapers might be smuggled across the Russo-German frontier in Poland or (later) across the Russo-Finnish border in the far north, and from there distributed across Russia in suitcases with false bottoms, in ‘breastplates’ (coats with literature sewn into the lining), and even in picture-frames and book-covers. Wafer-thin paper was used, and the margins might be cut off to reduce weight further.33

Because demand exceeded the supply that could be smuggled, efforts to run illegal print-shops were relentless. The ‘Caucasian Fruit Shop’ in Moscow’s Rozhdestvensky Boulevard, for instance, was the front for a secret printing-press in the basement. The ‘shopkeeper’ was a party member, and deliveries of printing supplies and dispatches of printed material were boxed as ‘Caucasian fruit’. The print-shop, a small room artificially lit, contained an American press, a work-bench, trays of type, and boxes of paper. The thud of the press could be heard in the shop above, so a bell was installed to give warning to stop when a customer entered. Urgent work would be done by two activists working through the night. The press existed for eight months, from September 1906 to April 1907, before being discovered by the police. In this period, 45 separate publications were issued. These included addresses, manifestos, pamphlets, journals, numerous leaflets (these with a total print-run of 1.5 million), and a small May Day poster (print-run 350,000).34

In this way, the exiled leadership reached deep into the Russian proletarian movement. But success depended upon a painstakingly constructed top-down network. Piatnitsky, appointed Odessa organiser in 1905, explains:

The organisation of that time, in Odessa as well as in the rest of Russia, was built from top to bottom on the principle of co-optation. In the plants and factories and in the workshops, the Bolsheviks who worked there invited (co-opted) workers whom they considered to be class-conscious and who were devoted to the cause.35

On this foundation, through careful selection, was constructed an edifice of district, regional, and city-wide committees.

City committees had the right to co-opt new members. When a city committee was arrested as a body, the central committee of the party designated one or more members to form a new committee, and those appointed co-opted suitable comrades from the workers of that region to complete the new committee.36

There was no other way. The risks were too high. Any open organisation would immediately have been penetrated by informers. Any amateur slip-up could lead the Tsarist police direct to a meeting-place and result in mass arrests. Underground revolutionary work required skill, experience, and exceptional precautions. Prison, torture, even death stalked the movement’s activists. Piatnitsky was mortified when one of his collaborators, a foundry worker, was caught with illegal literature:

They beat Solomon Rogut until he lost consciousness, and dragged him naked from the police station to the police headquarters, demanding the names of his comrades and where he got the literature … Solomon Rogut was sent to the Kovno prison. A month later, we learned that he had hanged himself (it was never established whether he really committed suicide or was beaten to death) … it left an indelible impression on me: I had caused the death of a comrade.37

For a revolutionary to remain at large in Tsarist Russia was to play an exhausting game of cat-and-mouse with the police. Activists travelled under false names, with made-up identities, carrying forged passports, often wearing disguises. If aware, or suspecting, that they were under surveillance, they would take long detours on the way to a rendezvous, dodging down alleyways and disappearing through tenements and backyards; jumping onto passing tramcars was an especially popular way of getting away from a police tail. More wearisome still was the lack of a home. Activists known to the police might have to change lodgings every few days. Piatnitsky would sometimes find himself trudging the streets or sleeping rough, unable to return to lodgings being watched by the police, unable to find alternative accommodation. Just to exist as a revolutionary could be a full-time occupation.38

Most veterans of the struggle endured periods of imprisonment and exile. The experience was variable. In the Lukyanovskaya prison in Kiev in 1902, the regime was exceptionally relaxed. Piatnitsky found it full of rebellious middle-class students, who had forced major concessions from the governor. On the political wing, where large numbers of Iskra-ists were being held, cell doors were open from morning till night, as was the door to the exercise yard, and inmates spent their time reading and debating. ‘The prison thus became my university’, Piatnitsky recalled. ‘I began to read systematically under the guidance of an educated Marxist who knew the revolutionary and Marxist literature very well.’39

Twelve years later, however, awaiting dispatch into Siberian exile, the Samara prison was far worse – head shaved, forced to wear prison uniform, no mixing with other politicals, hard labour cleaning cells, solitary confinement for minor offences, strip searches in the bitter cold. After a six-month wait, the passage to Siberia was made partly on foot, sleeping in filthy peasant huts without washing facilities; ‘there were biting frosts with snow-storms which made our progress on the snow-covered roads difficult’. The end of the long trek was the benighted wilderness village of Fedino, where the inhabitants slept in their clothing all year round, the beds, walls, and floorboards were infested with bugs and cockroaches, and life was ‘unbearably dull’.40

Again and again, organisation was destroyed by mass arrests and had to be built anew, the scattered fragments reassembled, new forces recruited to replace those lost to the prisons. Long before the final split with the Mensheviks in 1912, this spider’s web, spread across Russia and connected by long threads to the exiled leadership abroad, was Lenin’s party. Here, in the revolutionary underground, under the searching gaze of the Tsarist police, there was no place for the half-hearted, the fair-weather friend, the salon intellectual. To operate in the netherworld of illegal activism required high levels of commitment and endurance. The revolutionary paper provided the cohesive. It was, explained Piatnitsky, ‘the centre of gravitation for all the heterogeneous revolutionary elements of the Russian working class’; and when Lenin lost control of Iskra and was forced to create a new organ – Vperyod (‘Forward’) – the same network distributed it, for ‘the transport apparatus in Russia was in the hands of the party majority’. Here, in the lower depths of the social order, the mole of history was at work: one of the secrets of the Bolshevik Revolution is that the activist vanguard of the RSDLP was, from the earliest days, instinctively Leninist.41

The effectiveness of this vanguard is incomprehensible if we imagine them to be the cult-like groupies of a remote guru – as the caricatures of Bolshevism would have it. Even had Lenin been ‘democratic-centralist’ in intent, he could not have been so in practice, since there was no mechanism for imposing the rule of exiled party leaders on a network of small, widely scattered, secretly organised socialist groups with whom communications were intermittent and highly tenuous. Indeed, any such thing would have been madness, for the leadership was in no position to know how, say, the Baku oil-workers, the Moscow textile-workers, or the Petersburg engineering-workers should best operate in the circumstances confronting them. Any attempt to presume such knowledge from an exile enclave in distant Zurich (or wherever) would, given the intensity of police repression, have been the height of irresponsibility, quite possibly exposing activists to arrest and whole groups to liquidation.

Here is Piatnitsky:

The initiative of the local party organisations, of the cells, was encouraged. Were the Bolsheviks of Odessa, or Moscow, or Baku, or Tiflis, always to have waited for directives from the Central Committee, the provincial committees, etc., which during the years of the reaction and of the war did not exist at all owing to arrests, what would have been the result? The Bolsheviks would not have captured the working masses and exercised any influence over them.42

The July Days of 1914

Lenin’s genius was embodied in the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which he led from 1902 to 1917. The Bolsheviks were a network of proletarian activists with a clear mission: to unite the masses, support their struggles, and fan the flames into a revolutionary conflagration powerful enough to destroy the Tsarist regime. Sometimes it was a matter of bare survival for tiny, scattered, hounded groups of revolutionaries in the most forbidding of circumstances. Other times it was a matter of opening the gates of the party to thousands of angry young workers brought to life by a great upsurge of struggle from below. As circumstances changed, to remain what they aspired to be – the revolutionary leadership of the Russian proletariat – the Bolsheviks had to be flexible, responsive, able to adapt, yet at the same time immune to both ‘liquidationism’ (a collapse into reformist acceptance of the existing social order) and ‘ultra-leftism’ (issuing slogans and calls to action that were too radical to evoke a mass response in current circumstances). Getting the balance right was a matter of constant adjustment as circumstances changed.

The 1905 Revolution had involved Lenin in a head-on collision with the party’s Old Guard, who feared ‘dilution’ in a sea of new members. The defeat of the revolution created a far more serious crisis. ‘The years of Stolypin’s counter-revolution’, reported Zinoviev,

were the most critical and most dangerous in the party’s existence … the party as such did not exist; it had disintegrated into tiny individual circles, which differed from the circles of the 1880s and early 1890s in that, following the cruel defeat that had been inflicted upon the revolution, their general atmosphere was extremely depressed.43

Under the hammer blows of repression, many Mensheviks became explicitly liquidationist, arguing for the abandonment of illegal work, the dissolution of underground networks, an exclusive focus on the economic struggles of the workers, and political support for the liberals in the Duma, the Tsarist semi-parliament set up in 1906. Many Bolsheviks, however, drew the opposite conclusion, arguing that a new revolutionary upsurge was imminent, that the underground was the only proper field of action, and that the Duma and other Tsarist institutions should be boycotted. Lenin opposed both the liquidators on the right and the sectarians on the left. ‘Since the accursed counter-revolution has driven us into this accursed pigsty [the Duma],’ he declared, ‘we shall work there, too, for the benefit of the revolution, without whining, but also without boasting.’44

The argument was not easily carried. ‘The whole of our party was fragmented into groups, sub-groups, and factions’, recalled Zinoviev. ‘In those hard days our central task consisted in assembling the party piece by piece, preparing its rebirth, and, above all, defending the principles of Marxism against all possible distortions.’45 The aim was always the same: proletarian insurrection in the cities, peasant revolution in the countryside, the overthrow of Tsarism. But strategy had to conform to the prevailing balance of class forces, with tactics geared to the confidence, consciousness, and combativity of the workers. Until the revolution burst forth again, even the Tsarist Duma could be used as a platform for propaganda. But only for that, as Lenin made clear: ‘The Bolsheviks regard direct struggle of the masses … as the highest form of the movement, and parliamentary activity without the direct action of the masses as the lowest form of the movement.’46

The downturn lasted from 1907 to 1911. Then the strike rate doubled in a year, and the movement seemed to be reviving. The regime overreacted. On 4 April 1912, with 6,000 workers on strike in the Lena goldfields in Siberia, the police opened fire and shot down more than 500 people. Nothing like it had happened since Bloody Sunday in January 1905. More workers – 500,000 – struck in protest in April 1912 than in the whole of the preceding four years. Nor was it momentary rage. May Day that year saw a massive 400,000-strong protest, and the industrial and political unrest continued for the next two years, reaching its peak in the first half of 1914, when almost 1.5 million workers took strike action, a level comparable with 1905. Most of the strikes were openly political.47

The Bolshevik Party surged. Lenin, determined to drive the liquidators out of the RSDLP, organised a party congress in Prague in January 1912. Other Social Democratic factions refused to attend (organising an alternative congress in Vienna in August). The result was that the Bolsheviks took full control of the RSDLP, since their party opponents, ‘the August Bloc’, lacked any real influence in the underground movement inside the country. The two tendencies – the split at the top, the balance on the ground – henceforward reinforced each other. Ideologically unified around an uncompromising revolutionary programme – encapsulated in the party’s ‘three whales’: the eight-hour day, the confiscation of landed estates, and a democratic republic – the Bolsheviks now consolidated their grip on the advanced workers. Reformists and intellectuals drifted away. The party became at once more Bolshevik and more proletarian.48 It also became younger: the veterans in their thirties (rarely older) were reinforced after 1912 by a flood of new members in their teens and twenties.49

Alexander Shlyapnikov, another veteran working-class activist, returned from exile in April 1914 and got a job in an engineering factory in the Vyborg district of St Petersburg. The place was in ferment. Life was an endless round of leafleting, paper drops, solidarity collections, clandestine discussions, mass meetings, strikes, rallies, demonstrations, clashes with the police.50

Every conflict, small or large, irrespective of its origin, provoked a protest strike or walk-out. Political meetings and skirmishes with the police were everyday occurrences. The workers began to make contacts among the soldiers at the nearby barracks … An extremely active part … was taken by women workers, the weavers and mill-girls: some of the soldiers were from the same villages as the women workers, but for the most part the young people came together on the basis of ‘interests of the heart’ … It was totally impossible to turn such troops against the workers.51

By early July 1914, Petersburg was on the brink of revolution. A token strike called by the Bolsheviks in solidarity with the oil-workers of Baku in the distant Caucasus erupted into a massive confrontation when state forces opened fire in the streets of the capital. The entire proletariat was soon in action as 300,000 workers joined a week-long general strike. Veterans of 1905 advised on the erection of barricades and wire entanglements using knocked-down telegraph poles. Factory workers blocked streets by overturning carts and lacing them with wire. Children ripped up cobblestones, and young workers hurled them at the Cossacks and the police. Across the city there were mounted charges, beatings, shootings, mass arrests. But when the workers returned to work, they did so unbeaten, their mood buoyant, expectant.52

Everyone was overjoyed and encouraged by the recent strike, which had united a huge army of labour in one vivid upsurge of anger. This solidarity could not be smashed either by the police, or by the ‘glorious’ Cossackry, or by the threats of starvation from the coalition of factory-owners … Everyone felt that a decisive and nationwide battle was just around the corner.53

But it was not. Suddenly, as if by magic, the movement dissolved into nothing. The Tsar had declared war on Germany, and the revolutionary mood was transformed into patriotic fervour. On 2 August, a huge crowd, wholly different in demeanour from those manning the barricades a few days before, assembled in the square outside the Winter Palace. White uniforms appeared briefly on the balcony and then retired – perhaps testing the popular mood? Then others appeared, and, reports the British journalist and writer Arthur Ransome, who was there,

this time the Tsar was indeed among them, showing himself to the people for the first time in many years, to be greeted with extraordinary emotion and a tremendous singing of the national anthem. The strikes of a few days before were forgotten. War, as so often before and after, had for the moment welded the nation into one, or had seemed to weld it.54

The Tsar’s declaration of war had been a gamble. How would an insurrectionary people react? Would they rally round the Tsar? Or would they follow the revolutionaries and proclaim the international solidarity of the working class?

Russia’s corrupt, vicious, tottering regime now had its answer. War had cauterised revolution. Nationalism had suffocated socialism. Portraits of the Tsar had replaced the banners of Bolshevism. Soon, millions would be marching to the front.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 3 (52-87) from A People’s History of the Russian Revolution, by Neil Faulkner (Pluto Press, 03.15.2017), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.