The Monroe Doctrine’s legacy demonstrates how easily defensive principles can be repurposed into rationales for dominance once power accumulates.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A Doctrine Born Defensive, Remembered as Destiny

When President James Monroe articulated what would become known as the Monroe Doctrine in December 1823, he did so from a position of vulnerability rather than strength. The United States was a young republic with limited military capacity, a fragile economy, and deep anxiety about the return of European imperial ambition to the Western Hemisphere after the Napoleonic Wars. The doctrine’s original language reflected this insecurity. It was framed as a warning against renewed colonization and external intervention, not as a declaration of American supremacy. Its purpose was defensive and circumstantial, aimed at preserving a precarious independence rather than asserting dominance.

Yet doctrines rarely remain tethered to their original context. As the nineteenth century progressed, the Monroe Doctrine was gradually detached from the conditions that produced it. What began as a cautious diplomatic statement was increasingly treated as a timeless principle, abstracted from Monroe’s anxieties and repurposed to suit new ambitions. The United States grew in territorial size, economic capacity, and military confidence, and the doctrine evolved alongside that growth. The shift was subtle but consequential. A policy meant to prevent imperial intrusion became a rationale for American authority, recast as an enduring mandate rather than a temporary warning.

This transformation depended on a crucial reinterpretation of proximity and power. As European influence in the hemisphere waned, American leaders began to assume that geographic closeness conferred special rights and responsibilities. Intervention was framed as stewardship, dominance as stability. The Monroe Doctrine was increasingly invoked not to restrain action but to justify it, providing ideological cover for territorial acquisition, political interference, and military presence. Over time, the doctrine ceased to function as a shield against empire and instead became a scaffold upon which a distinctly American form of imperial entitlement was constructed.

Understanding this evolution is essential for grasping the doctrine’s modern afterlife. The language of destiny, inevitability, and rightful influence that came to surround the Monroe Doctrine did not emerge fully formed in 1823. It was assembled over decades through habit, success, and repetition. By the early twentieth century, the belief that American power carried with it a hemispheric mandate had hardened into common sense. That mindset continues to surface in contemporary rhetoric about territory, security, and acquisition. To trace the Monroe Doctrine from defensive statement to remembered destiny is to uncover the intellectual roots of a political logic that still shapes how the United States imagines its place in the world.

1823 and the Original Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine emerged from a moment of profound international uncertainty rather than confident assertion. In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, European powers gathered under the banner of the Holy Alliance openly discussed the restoration of monarchical authority and colonial order. For the United States, the prospect of renewed European intervention in Latin America posed both a strategic and ideological threat. The young republic lacked the military capacity to enforce its will, and its economy remained closely tied to transatlantic trade. Monroe’s message to Congress reflected this precarious position. It was less a proclamation of dominance than an attempt to draw a diplomatic boundary through words where force was unavailable.

The doctrine itself rested on two interlocking principles: non-colonization and non-intervention. Monroe declared that the Western Hemisphere was no longer open to European colonization and that European powers should refrain from interfering in the affairs of newly independent American states. Just as important, though often overlooked, was the reciprocal restraint embedded in the doctrine. The United States pledged not to interfere in existing European colonies or internal European affairs. This symmetry reveals the doctrine’s defensive character. It was designed to stabilize a fragile international balance, not to license unilateral American action.

British power played a decisive but understated role in shaping this posture. The Royal Navy, not American arms, provided the practical enforcement behind the doctrine’s warning. British commercial interests aligned with American concerns, as an independent Latin America offered open markets free from mercantilist restriction. This convergence allowed the United States to issue a bold diplomatic statement without bearing its costs. The Monroe Doctrine thus functioned as a strategic partnership cloaked in nationalist language, its effectiveness dependent on external power rather than domestic strength.

In its original form, the Monroe Doctrine lacked the mechanisms and ambitions of an imperial policy. It articulated no enforcement strategy, claimed no right of intervention, and asserted no American authority over neighboring states. Its significance lay in its rhetorical framing rather than its operational capacity. Only later would its language be stripped of context and repurposed as precedent. In 1823, the doctrine was an act of diplomatic anxiety, not imperial confidence, its meaning contingent on circumstances that subsequent generations would conveniently forget.

From Principle to Precedent: Early Reinterpretations

In the decades following 1823, the Monroe Doctrine began to drift from its original defensive moorings. As European threats receded and American confidence grew, policymakers increasingly treated the doctrine not as a situational warning but as an enduring principle. This shift did not occur through formal revision or legislative action. It emerged gradually through usage. Each invocation subtly altered the doctrine’s meaning, transforming it from a response to specific circumstances into a flexible precedent that could be adapted to new ambitions.

Territorial expansion accelerated this reinterpretation. The United States’ rapid growth across the continent fostered a sense that history itself favored American enlargement. Success bred assumption. As borders expanded westward and European influence declined, restraint came to appear unnecessary, even outdated. The Monroe Doctrine was increasingly cited not to prevent external interference but to assert American initiative. Its original symmetry faded as the United States abandoned the idea that its own actions required comparable limitation.

Diplomatic practice reinforced this evolution. American officials began invoking the doctrine selectively, emphasizing its prohibition against European involvement while ignoring its reciprocal commitments. Intervention was reframed as prevention. Influence became guardianship. The doctrine’s language proved elastic enough to accommodate these reinterpretations, allowing policymakers to claim continuity even as they departed from Monroe’s intent. What had once been a warning against empire slowly became a rhetorical shield for expanding authority.

By mid-century, the Monroe Doctrine functioned less as a policy than as a habit of thought. It established an expectation that the United States possessed a special role in the hemisphere, one grounded in geography rather than consent. This conceptual shift was crucial. Once the doctrine became precedent, its invocation no longer required justification. It normalized the belief that American power carried with it a hemispheric mandate, setting the stage for the more explicit expansionist ideologies that would soon follow.

Manifest Destiny and the Moralization of Expansion

By the 1840s, the reinterpretation of the Monroe Doctrine converged with a broader ideological current that transformed expansion into moral obligation. Manifest Destiny fused nationalism, Protestant theology, and racial hierarchy into a coherent narrative of inevitability. Expansion was no longer framed merely as advantageous or defensive. It was presented as righteous. The United States, according to this logic, was chosen to spread civilization, liberty, and order across the continent. This moral framing profoundly altered how power was justified, allowing territorial growth to appear not only permissible but virtuous.

The language of destiny masked the material realities of conquest. Westward expansion involved warfare, coercion, and dispossession, particularly of Indigenous nations whose sovereignty was systematically denied. Yet these actions were recast as tragic necessities or benevolent progress. The moral narrative surrounding Manifest Destiny displaced questions of legitimacy with appeals to historical purpose. If expansion was ordained, resistance could be dismissed as obstruction to progress rather than as political opposition. This logic normalized entitlement by embedding it within a story of national fulfillment.

Manifest Destiny also reshaped the Monroe Doctrine’s function within American political thought. What had once been a boundary against European empire now served as a hemispheric extension of continental logic. The same assumptions that justified removal, annexation, and settlement within North America were projected outward. The Western Hemisphere became an expanded frontier, its political diversity subordinated to a singular American trajectory. Sovereignty was increasingly measured by conformity to American norms rather than by legal independence or cultural autonomy.

Racial ideology played a central role in this moralization. Anglo-American identity was cast as inherently superior, capable of self-government and therefore entitled to rule. Latin American states and Indigenous societies were depicted as unstable, backward, or incapable of sovereignty without guidance. These assumptions did not merely rationalize expansion. They structured policy. Intervention could be justified as assistance, domination as tutelage. The moral language of Manifest Destiny thus provided ethical cover for actions that closely resembled the imperial practices the Monroe Doctrine had originally opposed.

By mid-century, expansionist entitlement had been fully normalized within American political culture. The success of continental growth reinforced the belief that power validated itself. Each acquisition, treaty, and military victory strengthened the assumption that American authority was both natural and beneficial. This moralization of expansion laid the groundwork for later hemispheric interventions and overseas acquisitions. Once destiny replaced restraint, the path from defense to dominance was not merely possible. It appeared inevitable.

The Monroe Doctrine and the Acquisition of Alaska

The purchase of Alaska in 1867 marked a pivotal moment in the evolution of American territorial logic. Unlike earlier continental expansion, Alaska lay far beyond the contiguous United States, separated by vast distances and lacking any immediate connection to settlement or statehood. Yet its acquisition was widely defended as prudent and inevitable. The logic used to justify the purchase drew implicitly on the Monroe Doctrine’s evolving assumptions. Territorial expansion was no longer confined by geography. Power, proximity in a hemispheric sense, and future strategic value were sufficient to legitimate acquisition.

Secretary of State William H. Seward framed the purchase not as imperial ambition but as foresight. Alaska was presented as a defensive buffer, a commercial opportunity, and a safeguard against European influence in North America. Russia’s willingness to sell was interpreted as an opening that the United States could not afford to ignore. The language of prevention remained prominent. Acquiring Alaska was cast as an act of restraint, a way to preempt rival empires rather than to extend American dominion. This rhetorical strategy echoed earlier reinterpretations of the Monroe Doctrine, in which intervention was justified as protection.

Public reaction to the purchase revealed the growing normalization of territorial entitlement. While critics derided Alaska as “Seward’s Folly,” opposition centered largely on cost and utility rather than legitimacy. Few questioned whether the United States had the right to acquire distant territory inhabited by Indigenous peoples. The absence of serious debate over sovereignty itself underscores how deeply expansionist assumptions had taken root. Acquisition was treated as a technical matter of negotiation between states, not as a political transformation affecting existing communities.

Alaska also functioned as a conceptual bridge between continental and hemispheric thinking. Its strategic position in the North Pacific reinforced the belief that American security depended on controlling key geographic nodes, even when they lay far from population centers. The purchase normalized the idea that non-contiguous territory could be integrated into the national sphere without altering core assumptions about governance or consent. Sovereignty was assumed to transfer cleanly through treaty, regardless of local realities. This logic would later reappear in American approaches to islands and overseas possessions.

By the late nineteenth century, Alaska stood as a precedent that quietly expanded the Monroe Doctrine’s reach. The doctrine had never explicitly sanctioned acquisition, yet its transformation into a broader ideology of hemispheric entitlement made such expansion appear natural. Alaska demonstrated that American power could be projected outward without abandoning the language of defense and prudence. It reinforced the belief that strategic necessity justified control, a belief that would shape later interventions and acquisitions. In this sense, Alaska was not an anomaly. It was a rehearsal for an American imperial posture that had learned to see possession as foresight rather than conquest.

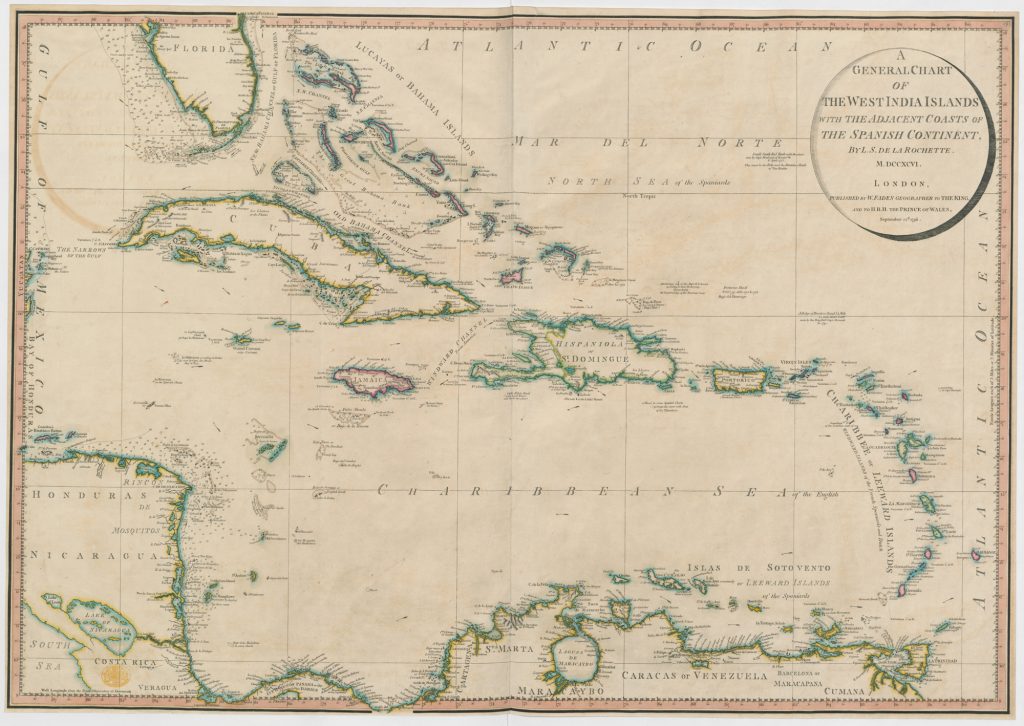

The Caribbean and Central America: From Influence to Control

By the late nineteenth century, the Monroe Doctrine’s transformation from diplomatic principle to instrument of power was most visible in the Caribbean and Central America. These regions, situated along vital trade routes and future canal corridors, became focal points of American strategic thinking. What had once been framed as a commitment to prevent European encroachment evolved into an active assertion of American authority. Influence gave way to control as policymakers increasingly treated instability in neighboring states as a legitimate cause for intervention.

Economic interests accelerated this shift. American investors, sugar producers, shipping firms, and banks acquired deep stakes in Caribbean and Central American economies. Political instability threatened those interests, and protection of capital was frequently conflated with protection of national security. The Monroe Doctrine provided a ready justification. Interventions were framed as necessary to preserve order, safeguard commerce, and prevent European creditors from intervening. Economic dependency thus became a lever through which sovereignty was constrained without formal annexation.

Military presence soon followed financial entanglement. The United States intervened repeatedly in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and Panama, often installing or supporting regimes favorable to American interests. These actions were rarely described as imperial conquest. Instead, they were presented as temporary measures undertaken for stabilization and reform. The distinction between influence and occupation blurred, as military governance, protectorates, and long-term bases became normalized features of American hemispheric power.

The construction of the Panama Canal crystallized this evolution. Control over the canal zone was justified as a necessity for global commerce and naval mobility, yet it required the effective domination of a sovereign state. The United States engineered Panama’s separation from Colombia and asserted permanent rights over the canal territory, demonstrating how strategic imperatives overrode principles of self-determination. The Monroe Doctrine, once a shield against empire, now functioned as a rationale for reshaping political boundaries to suit American needs.

By the early twentieth century, American dominance in the Caribbean and Central America had become routine. Intervention no longer required elaborate justification. It was assumed that proximity conferred responsibility and that responsibility authorized control. The language of order, stability, and progress masked a system in which sovereignty was conditional and subject to American approval. This regional pattern of influence hardened into expectation, reinforcing a hemispheric mindset in which intervention was not an exception but a governing principle. The Monroe Doctrine had completed its transformation, no longer a warning to outsiders but a license for American power.

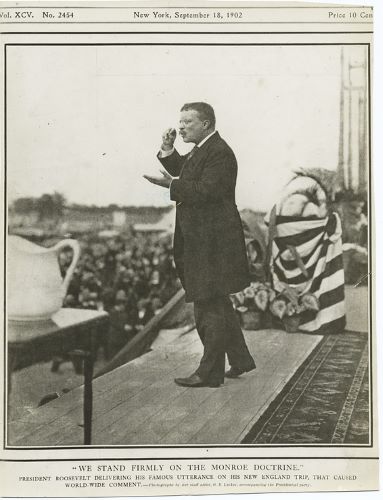

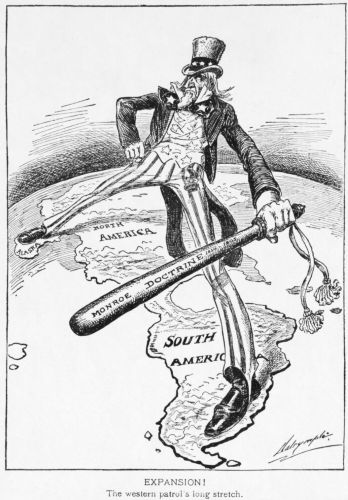

The Roosevelt Corollary and the Explicit Turn to Policing

The Roosevelt Corollary marked the moment when the Monroe Doctrine’s long drift toward entitlement became explicit policy. In his 1904 annual message to Congress, President Theodore Roosevelt asserted that chronic instability or wrongdoing in the Western Hemisphere might require intervention by a “civilized nation,” and that the United States was both willing and obligated to assume that role. This was not presented as a departure from Monroe’s original doctrine but as its logical extension. The language of defense gave way to the language of enforcement. The United States now claimed the right to act not merely against European intrusion but against the internal affairs of neighboring states.

Roosevelt’s formulation reframed sovereignty as conditional rather than absolute. Political independence remained nominally intact, but only so long as states behaved in ways deemed acceptable by Washington. Financial insolvency, social unrest, or political disorder could trigger intervention. The corollary thus introduced a new standard of legitimacy, one defined externally and enforced unilaterally. Sovereignty was no longer a fixed status but a privilege contingent on performance, measured against American expectations of order and responsibility.

Debt and finance became central justifications for this policing role. European powers had long used debt collection as a pretext for intervention, and Roosevelt argued that American action was necessary to prevent such intrusions. By assuming responsibility for stabilizing finances and collecting customs revenues, the United States positioned itself as a hemispheric regulator. This rationale framed intervention as protective rather than predatory, even as it transferred economic control from European creditors to American administrators. The corollary thus replaced foreign empire with domestic oversight while preserving the structure of domination.

The practical application of the Roosevelt Corollary was swift and extensive. U.S. forces intervened in the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and elsewhere to impose financial controls and political order. These interventions were often prolonged, involving direct administration rather than temporary mediation. The claim that policing was exceptional quickly eroded. Enforcement became routine, and routine enforcement normalized the idea that the United States possessed a standing mandate to intervene wherever instability appeared. The hemisphere was no longer merely protected. It was supervised.

Crucially, the Roosevelt Corollary did not provoke widespread domestic opposition. Many Americans viewed policing as a burden reluctantly assumed for the greater good. This perception reinforced national self-image as benevolent rather than imperial. The distinction between empire and responsibility allowed expansion of power without corresponding moral reckoning. By framing control as obligation, Roosevelt neutralized the language of conquest while institutionalizing its effects. Empire was denied even as its mechanisms were perfected.

The Roosevelt Corollary completed the Monroe Doctrine’s transformation from warning to warrant. What had begun as a statement against European imperialism culminated in an assertion of American authority over the hemisphere’s political life. The corollary formalized a habit of intervention that would persist long after Roosevelt left office. It embedded entitlement into doctrine, policy, and expectation, ensuring that American power would be exercised not only against external rivals but over neighboring societies themselves. In doing so, it laid the groundwork for a century of intervention justified not by conquest, but by the assumed right to police.

Normalizing Control: Law, Habit, and American Self-Perception

By the early twentieth century, American intervention in the Western Hemisphere had ceased to appear exceptional. What began as episodic responses to perceived crises hardened into routine practice, reinforced through repetition rather than debate. Each intervention created precedent, and precedent gradually became expectation. Control was normalized not through dramatic declarations of empire but through the quiet accumulation of habits. Intervention became the default response to instability, and restraint came to seem negligent rather than principled.

Law played a crucial role in this normalization. Executive authority expanded through repeated assertions of necessity, often without formal congressional declarations of war. Treaties, financial agreements, and protectorate arrangements provided legal scaffolding that cloaked coercion in legitimacy. Courts rarely challenged these practices, and international law offered little resistance, having long privileged effective control over moral consent. Over time, legality followed power rather than constrained it. What the United States did repeatedly came to be understood as what it was permitted to do.

Habit reinforced legality. Policymakers, diplomats, and military planners internalized the assumption that the hemisphere fell within a unique American sphere of responsibility. New crises were interpreted through familiar frameworks, drawing on established templates of intervention, occupation, and supervision. The institutional memory of control ensured continuity even as administrations changed. American power operated less as a conscious assertion than as an inherited routine, reproduced through bureaucratic momentum rather than ideological fervor.

This process reshaped American self-perception. The United States increasingly imagined itself not as an empire but as an indispensable stabilizer, reluctantly managing a disorderly neighborhood. Intervention was framed as burden rather than benefit, reinforcing a narrative of moral exceptionalism. The language of policing, assistance, and reform obscured the reality of dominance, allowing Americans to reconcile expansive power with anti-imperial self-image. Control was normalized precisely because it was denied as such.

By embedding entitlement within law and habit, the United States insulated its actions from scrutiny. Questions of legitimacy were displaced by appeals to precedent, responsibility, and necessity. Once control became ordinary, alternatives appeared unrealistic or dangerous. The hemisphere was no longer a collection of sovereign polities but a managed space whose stability was assumed to depend on American oversight. This normalization of control completed the intellectual arc that began with the Monroe Doctrine, transforming a defensive posture into an enduring assumption of authority.

From Hemisphere to Globe: The Doctrine’s Afterlife

By the mid-twentieth century, the logic that had once been confined to the Western Hemisphere began to escape its geographic bounds. The Monroe Doctrine no longer functioned solely as a regional policy. It had matured into a general orientation toward power, one that assumed the legitimacy of intervention wherever American security or interests were perceived to be at stake. The transition was not announced as doctrinal change. It unfolded through practice, as habits of hemispheric control were exported into a global context shaped by world war, decolonization, and ideological rivalry.

The Cold War accelerated this expansion. Containment theory mapped neatly onto earlier assumptions of entitlement, recasting intervention as defense against communism rather than as assertion of dominance. Regime manipulation, covert operations, and military presence were justified as necessary to preserve global stability, echoing earlier claims about order in the Caribbean and Central America. The distinction between hemisphere and world dissolved as American policymakers treated distant regions as extensions of a familiar strategic landscape. The Monroe Doctrine survived not as text, but as mindset.

This globalization of entitlement further insulated American power from self-critique. Actions abroad were framed as reactive, reluctant, and indispensable, reinforcing narratives of exceptionalism first developed during hemispheric policing. Sovereignty elsewhere was treated as conditional, dependent on alignment with American priorities. Just as financial instability or political disorder once invited intervention in the Caribbean, ideological deviation now justified involvement in Asia, the Middle East, and beyond. The mechanisms differed, but the underlying assumptions remained strikingly consistent.

The afterlife of the Monroe Doctrine thus reveals its most enduring legacy. What began as a defensive statement against European empire became a transferable logic of control, capable of adapting to new threats and new theaters. Its power lay not in formal invocation but in its normalization of entitlement itself. By the time contemporary leaders speak casually of acquisition, influence, or strategic necessity beyond national borders, they draw upon a tradition that has long since outgrown its original hemisphere. The Monroe Doctrine’s true afterlife is not geographic. It is conceptual, shaping how power continues to imagine its own legitimacy.

Conclusion: From Monroe to “Don-roe”

The history of the Monroe Doctrine is not a story of sudden betrayal or cynical invention. It is a story of gradual transformation, in which defensive language hardened into entitlement through repetition, success, and reinterpretation. What began in 1823 as a fragile assertion of autonomy by a weak republic became, over the course of a century, a durable justification for intervention, acquisition, and control. The doctrine did not change because it was rewritten. It changed because it was used, again and again, in contexts far removed from its original purpose.

This evolution reveals how power reshapes memory. Later generations remembered the Monroe Doctrine not as Monroe articulated it, but as it functioned once the United States possessed the capacity to enforce its will. The symmetry, restraint, and anxiety embedded in the original statement faded, replaced by confidence and assumption. Proximity became permission. Capability became right. By the time the United States asserted authority across the Caribbean, Central America, and beyond, the intellectual groundwork for entitlement had long been laid. Control appeared not as ambition, but as inheritance.

The recent reemergence under President Donald Trump of acquisitionist rhetoric exposes the persistence of this mindset. When contemporary political figures speak of territory as negotiable property, strategic asset, or rightful extension of national interest, they echo a long tradition rather than depart from it. The so-called “Don-roe Doctrine” is not an aberration. It is a blunt restatement of assumptions that have circulated in American political thought since the nineteenth century. What has changed is not the logic, but the candor with which it is expressed.

Understanding this continuity matters because it clarifies what is at stake. The question is not whether the United States has the power to assert control, but whether it can disentangle legitimacy from entitlement. The Monroe Doctrine’s legacy demonstrates how easily defensive principles can be repurposed into rationales for dominance once power accumulates. To confront contemporary claims of territorial leverage requires more than rebutting individual statements. It requires recognizing the historical grammar that makes such statements intelligible, plausible, and repeatable. Only by exposing that grammar can alternative visions of sovereignty, grounded in consent rather than assumption, be meaningfully imagined.

Bibliography

- Benton, Lauren. A Search for Sovereignty: Law and Geography in European Empires, 1400–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Gaddis, John Lewis. Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of American National Security Policy during the Cold War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Gilderhus, Mark T. “The Monroe Doctrine: Meanings and Implications.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 36:1 (2006): 5-16.

- Haycox, Stephen W. Alaska: An American Colony. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002.

- Herring, George C. From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Horsman, Reginald. Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Immerman, Richard H. Empire for Liberty: A History of American Imperialism from Benjamin Franklin to Paul Wolfowitz. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Kramer, Paul A. The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- LaFeber, Walter. The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860–1898. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1963.

- McCoy, Alfred W. Policing America’s Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009.

- McDougall, Walter A. Promised Land, Crusader State: The American Encounter with the World since 1776. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997.

- Mitchener, Kris James and Marc Weidenmier. “Empire, Public Goods, and the Roosevelt Corollary.” The Journal of Economic History 63:3 (2005): 658-692.

- Naske, Claus-M., and Herman E. Slotnick. Alaska: A History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1981.

- Perez, Louis A. Jr. Cuba and the United States: Ties of Singular Intimacy. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1967.

- Perkins, Dexter. The Monroe Doctrine, 1823–1826. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1927.

- Roosevelt, Theodore. The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, Annual Message to Congress, 1904.

- Sexton, Jay. The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Hill and Wang, 2011.

- Smith, Anthony D. Nationalism and Modernism. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Smith, Tony. America’s Mission: The United States and the Worldwide Struggle for Democracy in the Twentieth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Weeks, William Earl. Building the Continental Empire: American Expansion from the Revolution to the Civil War. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1996.

- Westad, Odd Arne. The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Wilentz, Sean. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. New York: W. W. Norton, 2005.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.19.2p026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.