Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Origins

Perspectives

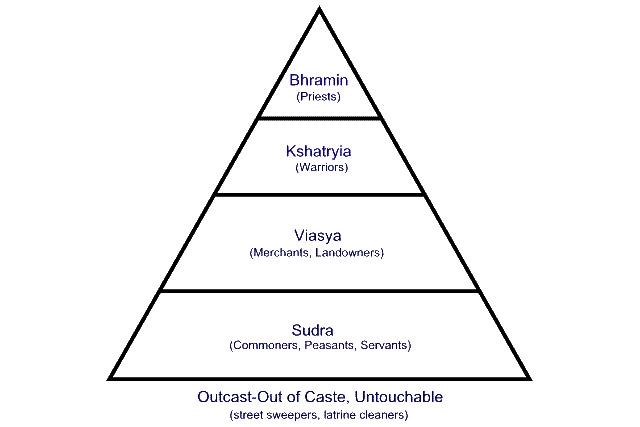

There are at least two perspectives for the origins of the caste system in ancient and medieval India, which focus on either ideological factors or on socio-economic factors.

- The first school focuses on the ideological factors which are claimed to drive the caste system and holds that caste is rooted in the four varnas. This perspective was particularly common among scholars of the British colonial era and was articulated by Dumont, who concluded that the system was ideologically perfected several thousand years ago and has remained the primary social reality ever since. This school justifies its theory primarily by citing the ancient law book Manusmriti and disregards economic, political or historical evidence.

- The second school of thought focuses on socioeconomic factors and claims that those factors drive the caste system. It believes caste to be rooted in the economic, political and material history of India. This school, which is common among scholars of the post-colonial era such as Berreman, Marriott, and Dirks, describes the caste system as an ever-evolving social reality that can only be properly understood by the study of historical evidence of actual practice and the examination of verifiable circumstances in the economic, political and material history of India. This school has focused on the historical evidence from ancient and medieval society in India, during the Muslim rule between the 12th and 18th centuries, and the policies of colonial British rule from 18th century to the mid-20th century.

The first school has focused on religious anthropology and disregarded other historical evidence as secondary to or derivative of this tradition. The second school has focused on sociological evidence and sought to understand the historical circumstances. The latter has criticised the former for its caste origin theory, claiming that it has dehistoricised and decontextualised Indian society.

Ritual Kingship Model

According to Samuel, referencing George L. Hart, central aspects of the later Indian caste system may originate from the ritual kingship system prior to the arrival of Brahmanism, Buddhism and Jainism in India. The system is seen in the South Indian Tamil literature from the Sangam period, dated to the third to sixth centuries CE.

This theory discards the Indo-Aryan varna model as the basis of caste, and is centred on the ritual power of the king, who was “supported by a group of ritual and magical specialists of low social status,” with their ritual occupations being considered ‘polluted’. According to Hart, it may be this model that provided the concerns with “pollution” of the members of low status groups. The Hart model for caste origin, writes Samuel, envisions “the ancient Indian society consisting of a majority without internal caste divisions and a minority consisting of a number of small occupationally polluted groups”.

Vedic Varnas

The varnas originated in Vedic society (c. 1500–500 BCE). The first three groups, Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Vaishya have parallels with other Indo-European societies, while the addition of the Shudras is probably a Brahmanical invention from northern India.

The varna system is propounded in revered Hindu religious texts, and understood as idealised human callings. The Purusha Sukta of the Rigveda and Manusmriti‘s comment on it, being the oft-cited texts. Counter to these textual classifications, many revered Hindu texts and doctrines question and disagree with this system of social classification.

Scholars have questioned the varna verse in Rigveda, noting that the varna therein is mentioned only once. The Purusha Sukta verse is now generally considered to have been inserted at a later date into the Rigveda, probably as a charter myth. Stephanie Jamison and Joel Brereton, professors of Sanskrit and Religious studies, state, “there is no evidence in the Rigveda for an elaborate, much-subdivided and overarching caste system”, and “the varna system seems to be embryonic in the Rigveda and, both then and later, a social ideal rather than a social reality”. In contrast to the lack of details about varna system in the Rigveda, the Manusmriti includes an extensive and highly schematic commentary on the varna system, but it too provides “models rather than descriptions”. Susan Bayly summarises that Manusmriti and other scriptures helped elevate Brahmins in the social hierarchy and these were a factor in the making of the varna system, but the ancient texts did not in some way “create the phenomenon of caste” in India.

Jatis

Jeaneane Fowler, a professor of philosophy and religious studies, states that it is impossible to determine how and why the jatis came in existence. Susan Bayly, on the other hand, states that jati system emerged because it offered a source of advantage in an era of pre-Independence poverty, lack of institutional human rights, volatile political environment, and economic insecurity.

According to social anthropologist Dipankar Gupta, guilds developed during the Mauryan period and crystallised into jatis in post-Mauryan times with the emergence of feudalism in India, which finally crystallised during the 7–12th centuries. However, other scholars dispute when and how jatis developed in Indian history. Barbara Metcalf and Thomas Metcalf, both professors of History, write, “One of the surprising arguments of fresh scholarship, based on inscriptional and other contemporaneous evidence, is that until relatively recent centuries, social organisation in much of the subcontinent was little touched by the four varnas. Nor were jati the building blocks of society.”

According to Basham, ancient Indian literature refers often to varnas, but hardly if ever to jatis as a system of groups within the varnas. He concludes that “If caste is defined as a system of group within the class, which are normally endogamous, commensal and craft-exclusive, we have no real evidence of its existence until comparatively late times.”

Untouchable Outcasts and the Varna System

The Vedic texts neither mention the concept of untouchable people nor any practice of untouchability. The rituals in the Vedas ask the noble or king to eat with the commoner from the same vessel. Later Vedic texts ridicule some professions, but the concept of untouchability is not found in them.

The post-Vedic texts, particularly Manusmriti mentions outcastes and suggests that they be ostracised. Recent scholarship states that the discussion of outcastes in post-Vedic texts is different from the system widely discussed in colonial era Indian literature, and in Dumont’s structural theory on caste system in India. Patrick Olivelle, a professor of Sanskrit and Indian Religions and credited with modern translations of Vedic literature, Dharma-sutras and Dharma-sastras, states that ancient and medieval Indian texts do not support the ritual pollution, purity-impurity premise implicit in the Dumont theory.

According to Olivelle, purity-impurity is discussed in the Dharma-sastra texts, but only in the context of the individual’s moral, ritual and biological pollution (eating certain kinds of food such as meat, going to bathroom). Olivelle writes in his review of post-Vedic Sutra and Shastra texts, “we see no instance when a term of pure/impure is used with reference to a group of individuals or a varna or caste”. The only mention of impurity in the Shastra texts from the 1st millennium is about people who commit grievous sins and thereby fall out of their varna. These, writes Olivelle, are called “fallen people” and considered impure in the medieval Indian texts. The texts declare that these sinful, fallen people be ostracised. Olivelle adds that the overwhelming focus in matters relating to purity/impurity in the Dharma-sastra texts concerns “individuals irrespective of their varna affiliation” and all four varnas could attain purity or impurity by the content of their character, ethical intent, actions, innocence or ignorance (acts by children), stipulations, and ritualistic behaviours.

Dumont, in his later publications, acknowledged that ancient varna hierarchy was not based on purity-impurity ranking principle, and that the Vedic literature is devoid of the untouchability concept.

Vedic Period (1500-1000 BCE)

During the time of the Rigveda, there were two varnas: arya varna and dasa varna. The distinction originally arose from tribal divisions. The Vedic tribes regarded themselves as arya (the noble ones) and the rival tribes were called dasa, dasyu and pani. The dasas were frequent allies of the Aryan tribes, and they were probably assimilated into the Aryan society, giving rise to a class distinction. Many dasas were however in a servile position, giving rise to the eventual meaning of dasa as servant or slave.

The Rigvedic society was not distinguished by occupations. Many husbandmen and artisans practised a number of crafts. The chariot-maker (rathakara) and metal worker (karmara) enjoyed positions of importance and no stigma was attached to them. Similar observations hold for carpenters, tanners, weavers and others.

Towards the end of the Atharvaveda period, new class distinctions emerged. The erstwhile dasas are renamed Shudras, probably to distinguish them from the new meaning of dasa as slave. The aryas are renamed vis or Vaishya (meaning the members of the tribe) and the new elite classes of Brahmins (priests) and Kshatriyas (warriors) are designated as new varnas. The Shudras were not only the erstwhile dasas but also included the aboriginal tribes that were assimilated into the Aryan society as it expanded into Gangetic settlements. There is no evidence of restrictions regarding food and marriage during the Vedic period.

Later Vedic Period (1000-600 BCE)

In an early Upanishad, Shudra is referred to as Pūşan or nourisher, suggesting that Shudras were the tillers of the soil. But soon afterwards, Shudras are not counted among the tax-payers and they are said to be given away along with the lands when it is gifted. The majority of the artisans were also reduced to the position of Shudras, but there is no contempt indicated for their work.

The Brahmins and the Kshatriyas are given a special position in the rituals, distinguishing them from both the Vaishyas and the Shudras. The Vaishya is said to be “oppressed at will” and the Shudra “beaten at will.”

Second Urbanization (500-200 BCE)

Our knowledge of this period is supplemented by Pali Buddhist texts. Whereas the Brahmanical texts speak of the four-fold varna system, the Buddhist texts present an alternative picture of the society, stratified along the lines of jati, kula and occupation. It is likely that the varna system, while being a part of the Brahmanical ideology, was not practically operative in the society. In the Buddhist texts, Brahmin and Kshatriya are described as jatis rather than varnas. They were in fact the jatis of high rank. The jatis of low rank were mentioned as chandala and occupational classes like bamboo weavers, hunters, chariot-makers and sweepers.

The concept of kulas was broadly similar. Along with Brahmins and Kshatriyas, a class called gahapatis (literally householders, but effectively propertied classes) was also included among high kulas. The people of high kulas were engaged in occupations of high rank, viz., agriculture, trade, cattle-keeping, computing, accounting and writing, and those of low kulas were engaged in low-ranked occupations such as basket-weaving and sweeping. The gahapatis were an economic class of land-holding agriculturists, who employed dasa-kammakaras (slaves and hired labourers) to work on the land. The gahapatis were the primary taxpayers of the state. This class was apparently not defined by birth, but by individual economic growth.

While there was an alignment between kulas and occupations at least at the high and low ends, there was no strict linkage between class/caste and occupation, especially among those in the middle range. Many occupations listed such as accounting and writing were not linked to jatis. Peter Masefield, in his review of caste in India, states that anyone could in principle perform any profession. The texts state that the Brahmin took food from anyone, suggesting that strictures of commensality were as yet unknown. The Nikaya texts also imply that endogamy was not mandated.

The contestations of the period are evident from the texts describing dialogues of Buddha with the Brahmins. The Brahmins maintain their divinely ordained superiority and assert their right to draw service from the lower orders. Buddha responds by pointing out the basic facts of biological birth common to all men and asserts that the ability to draw service is}} could become dasas and vice versa. This form of social mobility was endorsed by Buddha.

Classical Period (320-650 CE)

The Mahabharata, whose final version is estimated to have been completed by the end of the fourth century, discusses the varna system in section 12.181, presenting two models. The first model describes varna as a colour-based system, through a character named Bhrigu, “Brahmins varna was white, Kshatriyas was red, Vaishyas was yellow, and the Shudras’ black”. This description is questioned by Bharadvaja who says that colors are seen among all the varnas, that desire, anger, fear, greed, grief, anxiety, hunger and toil prevails over all human beings, that bile and blood flow from all human bodies, so what distinguishes the varnas, he asks. The Mahabharata then declares, “There is no distinction of varnas. This whole universe is Brahman. It was created formerly by Brahma, came to be classified by acts.”

The epic then recites a behavioural model for varna, that those who were inclined to anger, pleasures and boldness attained the Kshatriya varna; those who were inclined to cattle rearing and living off the plough attained the Vaishya varna; those who were fond of violence, covetousness and impurity attained the Shudra varna. The Brahmin class is modeled in the epic as the archetype default state of man dedicated to truth, austerity and pure conduct. In the Mahabharata and pre-medieval era Hindu texts, according to Hiltebeitel, “it is important to recognise, in theory, varna is nongenealogical. The four varnas are not lineages, but categories”.

Adi Purana, an 8th-century text of Jainism by Jinasena, is the first mention of varna and jati in Jain literature. Jinasena does not trace the origin of varna system to Rigveda or to Purusha, but to the Bharata legend. According to this legend, Bharata performed an “ahimsa-test” (test of non-violence), and during that test all those who refused to harm any living beings were called as the priestly varna in ancient India, and Bharata called them dvija, twice born. Jinasena states that those who are committed to the principle of non-harming and non-violence to all living beings are deva-Brahmaṇas, divine Brahmins.

The text Adipurana also discusses the relationship between varna and jati. According to Padmanabh Jaini, a professor of Indic studies, in Jainism and Buddhism, the Adi Purana text states “there is only one jati called manusyajati or the human caste, but divisions arise on account of their different professions”.[107] The caste of Kshatriya arose, according to Jainism texts, when Rishabha procured weapons to serve the society and assumed the powers of a king, while Vaishya and Shudra castes arose from different means of livelihood they specialised in.

Late Classical and Early Medieval Period (650-1400 CE)

Scholars have tried to locate historical evidence for the existence and nature of varna and jati in documents and inscriptions of medieval India. Supporting evidence for the existence of varna and jati systems in medieval India has been elusive, and contradicting evidence has emerged.

Varna is rarely mentioned in the extensive medieval era records of Andhra Pradesh, for example. This has led Cynthia Talbot, a professor of History and Asian Studies, to question whether varna was socially significant in the daily lives of this region. The mention of jati is even rarer, through the 13th century. Two rare temple donor records from warrior families of the 14th century claim to be Shudras. One states that Shudras are the bravest, the other states that Shudras are the purest. Richard Eaton, a professor of History, writes, “anyone could become warrior regardless of social origins, nor do the jati—another pillar of alleged traditional Indian society—appear as features of people’s identity. Occupations were fluid.” Evidence shows, according to Eaton, that Shudras were part of the nobility, and many “father and sons had different professions, suggesting that social status was earned, not inherited” in the Hindu Kakatiya population in the Deccan region between the 11th and 14th centuries.

In Tamil Nadu region of India, studied by Leslie Orr, a professor of Religion, “Chola period inscriptions challenge our ideas about the structuring of (south Indian) society in general. In contrast to what Brahmanical legal texts may lead us to expect, we do not find that caste is the organising principle of society or that boundaries between different social groups is sharply demarcated.” In Tamil Nadu the Vellalar were during ancient and medieval period the elite caste who were major patrons of literature.

For northern Indian region, Susan Bayly writes, “until well into the colonial period, much of the subcontinent was still populated by people for whom the formal distinctions of caste were of only limited importance; Even in parts of the so-called Hindu heartland of Gangetic upper India, the institutions and beliefs which are now often described as the elements of traditional caste were only just taking shape as recently as the early eighteenth century—that is the period of collapse of Mughal period and the expansion of western power in the subcontinent.”

For western India, Dirk Kolff, a professor of Humanities, suggests open status social groups dominated Rajput history during the medieval period. He states, “The omnipresence of cognatic kinship and caste in North India is a relatively new phenomenon that only became dominant in the early Mughal and British periods respectively. Historically speaking, the alliance and the open status group, whether war band or religious sect, dominated medieval and early modern Indian history in a way descent and caste did not.”

Medieval era, Islamic Sultanates and Mughal Period (1000-1750)

Early and mid 20th century Muslim historians, such as Hashimi in 1927 and Qureshi in 1962, proposed that “caste system was established before the arrival of Islam”, and it and “a nomadic savage lifestyle” in the northwest Indian subcontinent were the primary cause why Sindhi non-Muslims “embraced Islam in flocks” when Arab Muslim armies invaded the region. According to this hypothesis, the mass conversions occurred from the lower caste Hindus and Mahayana Buddhists who had become “corroded from within by the infiltration of Hindu beliefs and practices”. This theory is now widely believed to be baseless and false.

Derryl MacLein, a professor of social history and Islamic studies, states that historical evidence does not support this theory, whatever evidence is available suggests that Muslim institutions in north-west India legitimised and continued any inequalities that existed, and that neither Buddhists nor “lower caste” Hindus converted to Islam because they viewed Islam to lack a caste system. Conversions to Islam were rare, states MacLein, and conversions attested by historical evidence confirms that the few who did convert were Brahmin Hindus (theoretically, the upper caste). MacLein states the caste and conversion theories about Indian society during the Islamic era are not based on historical evidence or verifiable sources, but personal assumptions of Muslim historians about the nature of Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism in northwest Indian subcontinent.

Richard Eaton, a professor of History, states that the presumption of a rigid Hindu caste system and oppression of lower castes in pre-Islamic era in India, and it being the cause of “mass conversion to Islam” during the medieval era suffers from the problem that “no evidence can be found in support of the theory, and it is profoundly illogical”.

Peter Jackson, a professor of Medieval History and Muslim India, writes that the speculative hypotheses about caste system in Hindu states during the medieval Delhi Sultanate period (~1200 to 1500) and the existence of a caste system as being responsible for Hindu weakness in resisting the plunder by Islamic armies is appealing at first sight, but “they do not withstand closer scrutiny and historical evidence”. Jackson states that, contrary to the theoretical model of caste where Kshatriyas only could be warriors and soldiers, historical evidence confirms that Hindu warriors and soldiers during the medieval era included other castes such as Vaishyas and Shudras. Further, there is no evidence, writes Jackson, that there ever was a “widespread conversion to Islam at the turn of twelfth century” by Hindus of lower caste. Jamal Malik, a professor of Islamic studies, extends this observation further, and states that “at no time in history did Hindus of low caste convert en masse to Islam”.

Jamal Malik states that caste as a social stratification is a well-studied Indian system, yet evidence also suggests that hierarchical concepts, class consciousness and social stratification had already occurred in Islam before Islam arrived in India. The concept of caste, or ‘qaum‘ in Islamic literature, is mentioned by a few Islamic historians of medieval India, states Malik, but these mentions relate to the fragmentation of the Muslim society in India. Zia al-Din al-Barani of Delhi Sultanate in his Fatawa-ye Jahandari and Abu al-Fadl from Akbar’s court of Mughal Empire are the few Islamic court historians who mention caste. Zia al-Din al-Barani’s discussion, however, is not about non-Muslim castes, rather a declaration of the supremacy of Ashraf caste over Ardhal caste among the Muslims, justifying it in Quranic text, with “aristocratic birth and superior genealogy being the most important traits of a human”.

Irfan Habib, an Indian historian, states that Abu al-Fadl’s Ain-i Akbari provides a historical record and census of the Jat peasant caste of Hindus in northern India, where the tax-collecting noble classes (Zamindars), the armed cavalry and infantry (warrior class) doubling up as the farming peasants (working class), were all of the same Jat caste in the 16th century. These occupationally diverse members from one caste served each other, writes Habib, either because of their reaction to taxation pressure of Muslim rulers or because they belonged to the same caste. Peasant social stratification and caste lineages were, states Habib, tools for tax revenue collection in areas under the Islamic rule.

The origin of caste system of modern form, in the Bengal region of India, may be traceable to this period, states Richard Eaton. The medieval era Islamic Sultanates in India utilised social stratification to rule and collect tax revenue from non-Muslims. Eaton states that, “Looking at Bengal’s Hindu society as a whole, it seems likely that the caste system—far from being the ancient and unchanging essence of Indian civilisation as supposed by generations of Orientalists—emerged into something resembling its modern form only in the period 1200–1500”.

Later Mughal Period (1700-1850)

Susan Bayly, an anthropologist, notes that “caste is not and never has been a fixed fact of Indian life” and the caste system as we know it today, as a “ritualised scheme of social stratification,” developed in two stages during the post-Mughal period, in 18th and early 19th century. Three sets of value played an important role in this development: priestly hierarchy, kingship, and armed ascetics.

With the Islamic Mughal empire falling apart in the 18th century, regional post-Mughal ruling elites and new dynasties from diverse religious, geographical and linguistic background attempted to assert their power in different parts of India. Bayly states that these obscure post-Mughal elites associated themselves with kings, priests and ascetics, deploying the symbols of caste and kinship to divide their populace and consolidate their power. In addition, in this fluid stateless environment, some of the previously casteless segments of society grouped themselves into caste groups. However, in 18th century writes Bayly, India-wide networks of merchants, armed ascetics and armed tribal people often ignored these ideologies of caste. Most people did not treat caste norms as given absolutes writes Bayly, but challenged, negotiated and adapted these norms to their circumstances. Communities teamed in different regions of India, into “collective classing” to mold the social stratification in order to maximise assets and protect themselves from loss. The “caste, class, community” structure that formed became valuable in a time when state apparatus was fragmenting, was unreliable and fluid, when rights and life were unpredictable.

In this environment, states Rosalind O’Hanlon, a professor of Indian history, the newly arrived colonial East India Company officials, attempted to gain commercial interests in India by balancing Hindu and Muslim conflicting interests, by aligning with regional rulers and large assemblies of military monks. The British Company officials adopted constitutional laws segregated by religion and caste. The legal code and colonial administrative practice was largely divided into Muslim law and Hindu law, the latter including laws for Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs. In this transitory phase, Brahmins together with scribes, ascetics and merchants who accepted Hindu social and spiritual codes, became the deferred-to-authority on Hindu texts, law and administration of Hindu matters.

While legal codes and state administration were emerging in India, with the rising power of the colonial Europeans, Dirks states that the late 18th-century British writings on India say little about caste system in India, and predominantly discuss territorial conquest, alliances, warfare and diplomacy in India. Colin Mackenzie, a British social historian of this time, collected vast numbers of texts on Indian religions, culture, traditions and local histories from south India and Deccan region, but his collection and writings have very little on caste system in 18th-century India.

During British Rule (1857-1947)

Basis

Although the varnas and jatis have pre-modern origins, the caste system as it exists today is the result of developments during the post-Mughal period and the British colonial regime, which made caste organisation a central mechanism of administration.

Jati were the basis of caste ethnology during the British colonial era. In the 1881 census and thereafter, colonial ethnographers used caste (jati) headings, to count and classify people in what was then British India (now India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Burma). The 1891 census included 60 sub-groups each subdivided into six occupational and racial categories, and the number increased in subsequent censuses. The British colonial era census caste tables, states Susan Bayly, “ranked, standardised and cross-referenced jati listings for Indians on principles similar to zoology and botanical classifications, aiming to establish who was superior to whom by virtue of their supposed purity, occupational origins and collective moral worth”.

While bureaucratic British officials completed reports on their zoological classification of Indian people, some British officials criticised these exercises as being little more than a caricature of the reality of caste system in India. The British colonial officials used the census-determined jatis to decide which group of people were qualified for which jobs in the colonial government, and people of which jatis were to be excluded as unreliable. These census caste classifications, states Gloria Raheja, a professor of Anthropology, were also used by the British officials over the late 19th century and early 20th century, to formulate land tax rates, as well as to frequently target some social groups as “criminal” castes and castes prone to “rebellion”.

The population then comprised about 200 million people, across five major religions, and over 500,000 agrarian villages, each with a population between 100 and 1,000 people of various age groups, which were variously divided into numerous castes. This ideological scheme was theoretically composed of around 3,000 castes, which in turn was claimed to be composed of 90,000 local endogamous sub-groups.

The strict British class system may have influenced the British colonial preoccupation with the Indian caste system as well as the British perception of pre-colonial Indian castes. British society’s own similarly rigid class system provided the British with a template for understanding Indian society and castes. The British, coming from a society rigidly divided by class, attempted to equate India’s castes with British social classes. According to David Cannadine, Indian castes merged with the traditional British class system during the British Raj.

Colonial administrator Herbert Hope Risley, an exponent of race science, used the ratio of the width of a nose to its height to divide Indians into Aryan and Dravidian races, as well as seven castes.

Jobs for Forward Castes

The role of the British Raj on the caste system in India is controversial. The caste system became legally rigid during the Raj, when the British started to enumerate castes during their ten-year census and meticulously codified the system. Between 1860 and 1920, the British segregated Indians by caste, granting administrative jobs and senior appointments only to the upper castes.

Targeting Criminal Castes and Their Isolation

Starting with the 19th century, the British colonial government passed a series of laws that applied to Indians based on their religion and caste identification. These colonial era laws and their provisions used the term “Tribes”, which included castes within their scope. This terminology was preferred for various reasons, including Muslim sensitivities that considered castes by definition Hindu, and preferred Tribes, a more generic term that included Muslims.

The British colonial government, for instance, enacted the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871. This law declared everyone belonging to certain castes to be born with criminal tendencies. Ramnarayan Rawat, a professor of History and specialising in social exclusion in Indian subcontinent, states that the criminal-by-birth castes under this Act included initially Ahirs, Gurjars and Jats, but its enforcement expanded by the late 19th century to include most Shudras and untouchables, such as Chamars, as well as Sannyasis and hill tribes. Castes suspected of rebelling against colonial laws and seeking self-rule for India, such as the previously ruling families Kallars and the Maravars in south India and non-loyal castes in north India such as Ahirs, Gurjars and Jats, were called “predatory and barbarian” and added to the criminal castes list. Some caste groups were targeted using the Criminal Tribes Act even when there were no reports of any violence or criminal activity, but where their forefathers were known to have rebelled against Mughal or British authorities,[168][169] or these castes were demanding labour rights and disrupting colonial tax collecting authorities.

The colonial government prepared a list of criminal castes, and all members registered in these castes by caste-census were restricted in terms of regions they could visit, move about in or people with whom they could socialise. In certain regions of colonial India, entire caste groups were presumed guilty by birth, arrested, children separated from their parents, and held in penal colonies or quarantined without conviction or due process. This practice became controversial, did not enjoy the support of all colonial British officials, and in a few cases this decades-long practice was reversed at the start of the 20th century with the proclamation that people “could not be incarcerated indefinitely on the presumption of [inherited] bad character”. The criminal-by-birth laws against targeted castes was enforced until the mid-20th century, with an expansion of criminal castes list in west and south India through the 1900s to 1930s. Hundreds of Hindu communities were brought under the Criminal Tribes Act. By 1931, the colonial government included 237 criminal castes and tribes under the act in the Madras Presidency alone.

While the notion of hereditary criminals conformed to orientalist stereotypes and the prevailing racial theories in Britain during the colonial era, the social impact of its enforcement was profiling, division and isolation of many communities of Hindus as criminals-by-birth.

Religion and Caste Segregated Human Rights

Eleanor Nesbitt, a professor of History and Religions in India, states that the colonial government hardened the caste-driven divisions in British India not only through its caste census, but with a series of laws in early 20th century. The British colonial officials, for instance, enacted laws such as the Land Alienation Act in 1900 and Punjab Pre-Emption Act in 1913, listing castes that could legally own land and denying equivalent property rights to other census-determined castes. These acts prohibited the inter-generational and intra-generational transfer of land from land-owning castes to any non-agricultural castes, thereby preventing economic mobility of property and creating consequent caste barriers in India.

Khushwant Singh a Sikh historian, and Tony Ballantyne a professor of History, state that these British colonial era laws helped create and erect barriers within land-owning and landless castes in northwest India. Caste-based discrimination and denial of human rights by the colonial state had similar impact elsewhere in British India.

Social Identity

Nicholas Dirks has argued that Indian caste as we know it today is a “modern phenomenon,” as caste was “fundamentally transformed by British colonial rule.” According to Dirks, before colonialism caste affiliation was quite loose and fluid, but the British regime enforced caste affiliation rigorously, and constructed a much more strict hierarchy than existed previously, with some castes being criminalised and others being given preferential treatment.

De Zwart notes that the caste system used to be thought of as an ancient fact of Hindu life and that contemporary scholars argue instead that the system was constructed by the British colonial regime. He says that “jobs and education opportunities were allotted based on caste, and people rallied and adopted a caste system that maximized their opportunity”. De Zwart also notes that post-colonial affirmative action only reinforced the “British colonial project that ex hypothesi constructed the caste system”.

Sweetman notes that the European conception of caste dismissed former political configurations and insisted upon an “essentially religious character” of India. During the colonial period, caste was defined as a religious system and was divorced from political powers. This made it possible for the colonial rulers to portray India as a society characterised by spiritual harmony in contrast to the former Indian states which they criticised as “despotic and epiphenomenal”, with the colonial powers providing the necessary “benevolent, paternalistic rule by a more ‘advanced’ nation”.

Further Development

Assumptions about the caste system in Indian society, along with its nature, evolved during British rule. Corbridge concludes that British policies of divide and rule of India’s numerous princely sovereign states, as well as enumeration of the population into rigid categories during the 10-year census, particularly with the 1901 and 1911 census, contributed towards the hardening of caste identities.

Social unrest during 1920s led to a change in this policy. From then on, the colonial administration began a policy of positive discrimination by reserving a certain percentage of government jobs for the lower castes.

In the round table conference held on August 1932, upon the request of Ambedkar, the then Prime Minister of Britain, Ramsay MacDonald made a Communal Award which awarded a provision for separate representation for the Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, Anglo-Indians, Europeans and Dalits. These depressed classes were assigned a number of seats to be filled by election from special constituencies in which voters belonging to the depressed classes only could vote. Gandhi went on a hunger strike against this provision claiming that such an arrangement would split the Hindu community into two groups. Years later, Ambedkar wrote that Gandhi’s fast was a form of coercion. This agreement, which saw Gandhi end his fast and Ambedkar drop his demand for a separate electorate, was called the Poona Pact.

After India achieved independence, the policy of caste-based reservation of jobs was formalised with lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

Other Theories and Observations

Smelser and Lipset propose in their review of Hutton’s study of caste system in colonial India the theory that individual mobility across caste lines may have been minimal in British India because it was ritualistic. They state that this may be because the colonial social stratification worked with the pre-existing ritual caste system.

The emergence of a caste system in the modern form, during the early British colonial rule in the 18th and 19th century, was not uniform in South Asia. Claude Markovits, a French historian of colonial India, writes that Hindu society in north and west India (Sindh), in late 18th century and much of 19th century, lacked a proper caste system, their religious identities were fluid (a combination of Saivism, Vaisnavism, Sikhism), and the Brahmins were not the widespread priestly group (but the Bawas were). Markovits writes, “if religion was not a structuring factor, neither was caste” among the Hindu merchants group of northwest India.

Contemporary

Caste Politics

Societal stratification, and the inequality that comes with it, still exists in India, and has been thoroughly criticised. Government policies aim at reducing this inequality by reservation, quota for backward classes, but paradoxically also have created an incentive to keep this stratification alive. The Indian government officially recognises historically discriminated communities of India such as the untouchables under the designation of Scheduled Castes, and certain economically backward castes as Other Backward Class.

Loosening of the Caste System

Leonard and Weller have surveyed marriage and genealogical records to study patterns of exogamous inter-caste and endogamous intra-caste marriages in a regional population of India in 1900–1975. They report a striking presence of exogamous marriages across caste lines over time, particularly since the 1970s. They propose education, economic development, mobility and more interaction between youth as possible reasons for these exogamous marriages.

A 2003 article in The Telegraph claimed that inter-caste marriage and dating were common in urban India. Indian societal and family relationships are changing because of female literacy and education, women at work, urbanisation, the need for two-income families, and global influences through television. Female role models in politics, academia, journalism, business, and India’s feminist movement have accelerated the change.

Caste-Related Violence

Independent India has witnessed caste-related violence. According to a 2005 UN report, approximately 31,440 cases of violent acts committed against Dalits were reported in 1996. The UN report claimed 1.33 cases of violent acts per 10,000 Dalit people. For context, the UN reported between 40 and 55 cases of violent acts per 10,000 people in developed countries in 2005. One example of such violence is the Khairlanji massacre of 2006.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 05.12.2004, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.