Whether the American experiment survives this chapter will depend on who the nation decides to be: spectators or citizens, courtiers or guardians.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The broadcast lights dim. A hush falls over the gathering of supporters. Then he emerges, stepping into a golden glow, fist raised, red tie aligned with the flag behind him. It is a moment of spectacle, designed for mass photo, viral clip and digital memory. A few days later, a graphic appears: a mock TIME magazine cover. He wears a crown. Bold letters: “LONG LIVE THE KING.” The post circulates on his own platform, then through channels tied to his office.

For a republic that prides itself on no kings, the declaration lands like a challenge. What does it mean when the nation’s chief executive signals not an equal subject of law, but a sovereign above it? As the image fades, the question remains: in that moment of performance, the mask reveals a mindset. One where the presidency becomes not simply an office, but a throne, not simply service, but sovereign rule.

Rhetoric and Language: The Voice of the Sovereign

When Trump told an audience of far-right students in 2019, “I have an Article II where I have the right to do whatever I want as president,” the crowd cheered as if he had recited scripture. C-SPAN footage captured the grin, the pause, the expectation of applause. The words were delivered with the cadence of revelation, as though the Constitution itself had been written to sanctify his personal will. The moment mattered less for its legal illiteracy than for what it revealed, a monarch’s conception of office in a republic built to reject monarchy.

Language has always been Trump’s instrument of enthronement. At the 2016 Republican National Convention, he promised, “I alone can fix it,” collapsing centuries of civic pluralism into one voice, one savior. Later, before a friendly television audience, he assured Sean Hannity he would be a “dictator, but only on day one,” the smirk signaling performance but the premise remaining intact: absolute command, even if fleeting, belongs to him. Such lines are not gaffes; they are creeds. They announce a political theology in which law bends to personality.

The pattern runs deeper than bombast. Trump rarely speaks of institutions, only of people who serve him or betray him, agencies that act properly when obedient, courts that are legitimate when favorable. In his rhetoric, constitutional power is not a framework of obligations but a reservoir of personal might, tapped at will. The pronouns tell the story: the presidency becomes my generals, my attorney general, my Supreme Court. The possessive pronoun is the crown jewel of the authoritarian tongue.

Even his metaphors of violence and purity echo the old royal lexicon. Political rivals are “traitors,” journalists are “enemies of the people,” and protesters as well as political opponents are “vermin” to be rooted out, all phrases that once justified purges in monarchies and empires. The vocabulary is not accidental. It re-centers politics around loyalty to a person rather than fidelity to a constitution. It transforms disagreement into sacrilege.

The danger in this language is cumulative. Each statement may sound like hyperbole, but together they create a moral architecture in which obedience equals patriotism and constraint equals betrayal. In the grammar of kings, power is indivisible. Trump’s rhetoric follows the same rule. Words become coronation, every rally a court, every repetition an oath of fealty to the speaker on stage.

Symbolism and Performance: Rituals of the Crown

Trump’s politics have always been as visual as they are verbal. The crown may be metaphorical, but it gleams through his stagecraft. When he enters a rally, it is not as a candidate or even as a president—it is as a spectacle. “Proud to be an American” blares, lights blaze crimson and gold, and he stands alone in a tableau framed by flags. Cameras rise to catch him from below, an angle filmmakers use to signal power. The choreography is not accidental. It borrows from monarchy’s oldest language: elevation, procession, and awe.

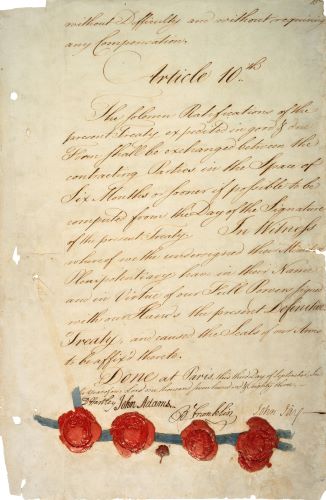

This aesthetic reached a kind of apotheosis in the image that appeared on his social platform, a doctored TIME magazine cover depicting Trump in regal pose beneath the words “LONG LIVE THE KING.” The post, circulated from his own account and echoed by allies, drew both laughter and alarm. Even some within his party flinched at its brazenness. Yet the image was revealing. It said the quiet part aloud: the dream of rule unencumbered by law, answerable only to loyalty and belief. The symbolism was so overt that a Philadelphia city council resolution later condemned it, calling it evidence of an anti-democratic mindset.

The kingly imagery is not new. Throughout his presidency, Trump surrounded himself with gilt and grandeur. The Oval Office became a backdrop for signing ceremonies arranged like royal audiences, guests arrayed in semicircles, cameras clicking as courtiers once would have bowed. When he invited cabinet members to praise him on live television, it mirrored the feudal ritual of homage. Each official took a turn reciting devotion. He smiled, not as a manager acknowledging reports, but as a sovereign accepting tribute.

Rallies, too, took on the rhythm of religious ceremony. Supporters chanted not policy demands but acclamations, “We love you!,” as though addressing divinity rather than a public servant. Merchandise bearing his face proliferated like icons, and at some gatherings, speakers compared him directly to biblical kings. The pageantry blurred political enthusiasm with worship. When followers wave banners declaring “Jesus is my Savior, Trump is my President,” they are not engaging in metaphor; they are merging the sacred with the civic.

Even his mannerisms contribute to the illusion. The exaggerated gestures, the long pauses for applause, the slow turning of the body toward each corner of the crowd, all mimic the ritualized movements of a monarch acknowledging subjects. His body language communicates what the Constitution denies him: permanence, grandeur, and inheritance. The crowd completes the illusion by treating those gestures as acts of grace.

To critics, these performances are theater. To his admirers, they are ceremony. And that distinction is the key. The rally becomes not a campaign event but a coronation repeated in miniature, each time reaffirming the myth that America is safest when ruled by one man’s will.

Institutional Acts: Governing as Monarch, Not President

Every authoritarian story begins the same way: with the slow corrosion of boundaries. Trump’s presidency followed that script with unnerving fidelity. It wasn’t just the language of kingship that signaled his belief in sovereign rule; it was how he governed. When Trump declared during the pandemic that he had “total authority” to decide when states would reopen, even Republican governors looked startled. Constitutional scholars immediately reminded the nation that the United States has no such thing as “total authority.” But Trump’s point was not legal; it was symbolic. He was performing the idea that his will defined the limits of the possible.

That impulse shaped his approach to every branch of government. Congress, in his view, existed to fund and applaud, not to investigate or restrain. When committees issued subpoenas, he ordered officials to ignore them. When inspectors general uncovered misuse of power, he dismissed or replaced them. The Department of Justice, designed to serve the law, was repeatedly treated as a personal firm of royal counselors, loyalty, not legality, being the measure of worth. The Constitution’s framers would have recognized this instantly. It was the very behavior they wrote the separation of powers to prevent.

Trump’s own words often confirmed what his actions displayed. He told reporters that Article II gave him the right to do “whatever I want.” He publicly urged the Justice Department to prosecute his critics, then later said a future administration would “go after” opponents who had “hurt” him. The pattern was clear: accountability was vengeance, independence was betrayal. Even the military, an institution carefully insulated from politics, became a stage prop for dominance. He posed with generals as though commanding legions, declaring himself the defender of “law and order” against domestic enemies.

The final months of his first term made the monarchical mindset unmistakable. As court after court rejected his false claims of election fraud, he cast judges as disloyal servants. He pressured state officials to “find” votes. And when none of it worked, he summoned his followers to Washington, promising the day would be “wild.” The resulting attack on the Capitol was less an aberration than an outcome of a philosophy: that loyalty to the leader outweighs duty to the republic.

In democracies, institutions are meant to absorb conflict and protect continuity. In monarchies, institutions exist to magnify the ruler’s will. Trump’s presidency inverted the American order, bending public office toward personal use and branding dissent as treason. Every time a limit held (when courts ruled against him, when state officials refused to comply) it did so not because he respected it, but because he momentarily failed to overcome it.

The danger, as his current campaign again makes clear, is that he learned from those failures. Promising to “root out the vermin” and to wield the presidency as a weapon against “enemies within,” he has redefined the office as an instrument of conquest. The king he imagines himself to be is not one of constitutional monarchy, balanced and ceremonial. It is the older kind, the one whose law begins and ends with his own decree.

Historical Analogues: From Louis XIV to Caesar and Beyond

History never repeats itself exactly, but it rhymes loudly enough to hear the echo. Trump’s conception of power follows a lineage older than the Constitution he swore to uphold. When Louis XIV of France declared “L’état, c’est moi” (I am the state) he was not being poetic. He was defining the very architecture of absolutism, one in which authority flowed from a single person by divine sanction. The image of the Sun King, radiant at the center of his court, projected order and splendor. But it also concealed the truth: the state existed to serve him, not the people. In Trump’s politics, the gold-plated penthouse and the red-hued rallies play the same role. The aesthetic of grandeur stands in for legitimacy.

The comparison extends beyond Versailles. The Roman model offers a closer fit. Julius Caesar began as a populist reformer who claimed to defend the people against a corrupt Senate. When his ambition crossed the Rubicon, he justified his coup as an act of necessity, a restoration of greatness. Caesar’s heirs learned the lesson: populist charisma could sanctify empire. Napoleon Bonaparte later revived it, crowning himself emperor before a stunned pope and insisting that his rule embodied the nation’s will. In each case, the transition from republic to autocracy began not with the rejection of democracy but with its redefinition. “The people” became a mirror reflecting one man’s image.

Trump’s rhetoric of national restoration, his fixation on loyalty, and his claim to speak for “real Americans” align neatly with this pattern. Like the Caesars and Bonapartes before him, he converts mass devotion into a mandate for absolute discretion. The elections that elevate him are not ends but coronations, affirmations of personal destiny. The republic becomes his inheritance. His constant refrain of “I’m your retribution” echoes the language of divine vengeance once reserved for kings who ruled by wrath and favor.

Even his relationship to truth follows the imperial precedent. Absolutist rulers have always treated reality as pliable clay, malleable, remade by decree. Louis XIV rewrote defeats into triumphs. Napoleon ordered official bulletins that turned stalemates into victories. Trump’s endless claims of stolen elections and imaginary conspiracies function the same way. When truth becomes whatever the ruler says it is, fact itself bends the knee.

Yet history also offers a warning. The absolutist myth always ends the same way, when the sovereign’s world collides with the weight of reality. Versailles collapsed into revolution. Caesar fell to daggers. Napoleon met his Waterloo. Each believed themselves destined, each learned that charisma cannot permanently suspend law or consequence. Whether democracy remembers those lessons will decide how this American version of the story concludes.

Supporter Psychology: The King and His Court

Every monarch requires subjects, and every authoritarian myth depends on believers. Trump’s ascent has never been merely a story of one man’s ambition; it is the story of a movement that finds comfort in hierarchy, meaning in belonging, and identity in the shadow of a single figure. To understand how the king in his own mind thrives, one must understand the court that sustains him.

Max Weber called it charismatic authority: legitimacy drawn not from law or tradition but from personal magnetism. Charisma fills the void when institutions fail to inspire trust. It asks for faith rather than reason. For Trump’s followers, that faith manifests in chants, merchandise, and testimony, a liturgy of loyalty that transcends policy. They do not rally for a platform; they rally for a presence. The bond is emotional, even devotional, and it grows stronger when outsiders ridicule it. To them, every indictment, every media criticism, every fact-check reinforces the feeling of persecution; and persecution is a powerful sacrament.

The religious overtones are no accident. For years, certain evangelical leaders have described Trump as a modern-day King Cyrus, the biblical ruler who freed the Jews and restored their temple despite his flaws. In that narrative, Trump’s sins become proof of divine purpose. This theological framing turns political obedience into spiritual duty: to oppose him is to oppose providence. Among his most fervent supporters, that idea fuses religion and nationalism into a single creed.

Sociologically, it functions like a medieval court. Loyalty earns access; dissent means exile. Those once close who fall from grace (attorneys, aides, generals) become heretics, cast out and denounced. In this world, reality is mediated through the ruler’s favor. When he praises someone, they exist. When he reviles them, they vanish. Supporters internalize that same logic, shaping their political universe around his moods and messages. His Truth Social posts become royal proclamations, dissected and exalted. His rallies become gatherings of the faithful, where participation affirms belonging.

The psychology of kingship appeals to deep currents in human nature: the desire for certainty, protection, and identity in a chaotic world. Democracy is noisy and slow; monarchy promises clarity and strength. Trump offers that simplicity, a father figure who will punish enemies and restore order. It is a myth of salvation through domination. Each time he frames himself as the victim of a corrupt elite, he renews the covenant: I suffer for you; therefore, you must defend me. It is emotional blackmail wrapped in populist theater.

Yet this devotion carries a cost. By replacing civic responsibility with personal allegiance, it hollows out the citizen’s role. The “people” become spectators rather than participants, cheering decrees instead of shaping policy. This is how republics decay, not by invasion or sudden collapse, but by voluntary surrender to the comfort of a king. When the crowd shouts “We love you!” and he replies “You’re very smart,” it completes a cycle of mutual flattery that feels like democracy but behaves like feudalism.

The irony is that his followers, many of whom distrust elites and revere freedom, are drawn into the oldest political trap in history: believing that liberty is safest when placed in the hands of one man. They see him as their protector from chaos, not realizing that in every age, the promise of the strongman has ended in chains.

Implications for Democracy: When the Republic Bows

Every democracy must occasionally confront its reflection and ask what it has become. In Trump’s mirror, the American republic appears not as a union of laws and institutions, but as a stage for one man’s will. His monarchical posture exposes a deeper weakness: a citizenry increasingly willing to trade complexity for command, and principle for personality. When the presidency becomes the measure of national virtue, the Constitution shrinks to parchment.

The founding generation anticipated this temptation. They designed a system of rival powers (executive, legislative, judicial) precisely to prevent the rise of another king. Federalist 51 warned that “ambition must be made to counteract ambition.” Trump’s appeal inverts that formula. His movement channels every grievance and insecurity into a single vessel, turning ambition into allegiance. What Madison built to restrain tyranny becomes fuel for it. Each institution that resists his demands is branded corrupt; each that submits becomes a servant of the crown.

We have seen this pattern before. When autocrats elsewhere dismantled their democracies, they began by discrediting their own governments. Courts became enemies, legislatures became obstacles, and the press became traitorous. The same language now flows from American lips. Trump’s promise to “root out the vermin” echoes twentieth-century despotism, invoking purification rather than persuasion. His threats to weaponize the Department of Justice and purge the civil service reimagine the presidency as a personal inquisition. These are not exaggerations, they are pledges spoken on camera, cheered by crowds who no longer flinch at words once unthinkable.

The implications reach beyond institutions. Democracy depends on shared reality: facts accepted even by opponents. But a politics built on kingship dissolves that consensus. When the ruler’s statements outweigh observable truth, the republic enters the realm of myth. In that world, loyalty becomes the only fact that matters. Officials swear fealty, voters become believers, and law bends to charisma. A government of laws cannot survive long in a nation that worships men.

Yet the danger is not only his. It belongs to everyone who lets exhaustion replace vigilance. Democracies do not collapse because one man crowns himself; they collapse because too many shrug as he does it. Each time citizens tolerate contempt for courts, threats against journalists, or the fantasy of “total authority,” they tighten the circle around their own freedom. The slow surrender of outrage is how republics bow.

Still, the design of the American experiment offers a paradoxical hope. The same system that limits presidents also empowers people. Congress can reassert oversight. Courts can enforce the law. Voters can reject the mythology of the strongman and demand something rarer than strength: humility. The founders placed faith not in men but in mechanisms, believing that reason could outlast passion. Whether they were right now depends on whether citizens still believe in the same bet.

Counter-Narratives and Pushback: “No Kings in America”

For every self-anointed monarch, there have always been subjects who refused to kneel. In the months after Trump’s “Long Live the King” post, opposition to that imagery came swiftly. A Philadelphia city council resolution condemned the post as proof of an authoritarian mindset, reaffirming that America “has no kings, only citizens.” The rebuke might seem symbolic, but symbols are the terrain where Trump wages his most effective battles. When a president plays at monarchy, it matters that the body politic answers, “No.”

Across civil society, the response has grown louder. Historians and constitutional scholars, from universities to civic forums, have revived public discussions about executive restraint, conversations once confined to classrooms but now resonating in town halls and podcasts. Journalists have adapted too, learning to treat spectacle not as entertainment but as evidence. Each fact-check, each exposure of falsified narratives, is a small act of republican maintenance, a hammer tap against the gilded veneer of infallibility.

The courts, often maligned as partisan, have at times provided the most tangible resistance. Judges appointed by Trump himself ruled against him when he sought to overturn the 2020 election, proving that the oath to the Constitution can still outweigh loyalty to its temporary occupant. State election officials, some under threat of violence, refused to fabricate results. Their defiance was not glamorous, but it was revolutionary in its simplicity: the rule of law held because ordinary people refused to let it break.

Protesters, too, have carried the old republican fire into the streets. The handmade signs (“No Kings in America”, “We the People Say No”) evoke the spirit of 1776 more authentically than any campaign slogan. Each march is a reminder that democracy’s endurance depends not on grandeur but on repetition: the continual re-assertion that authority belongs downward, not upward. Even within conservative circles, voices of principle still surface. Former officials, military leaders, and legal scholars, many of whom once served under Trump, have warned that another term modeled on vengeance would dissolve the last pretenses of constraint. Their dissent, though costly, keeps alive a fading virtue: loyalty to country over crown.

The press, the courts, the protester, the scholar, they are the counter-monarchy of democracy. Together they form what Trump most despises: a network of limits. Each insists that leadership is service, not dominion. Each defends the idea that no citizen, however adored or feared, stands above the law. Their strength lies not in charisma but in persistence. For every coronation staged in rhetoric or rally, there remains a chorus reminding him, and us, that the United States began with a rejection of kings.

And yet, resistance alone is not renewal. The antidote to authoritarian theater is not mere outrage but civic imagination: the belief that democracy can still be something better than a personality cult. The task ahead is not only to unmask the would-be monarch but to reawaken the citizen. The oath belongs to all of us.

Conclusion: The Crown and the Constitution

In a republic founded by revolution against a king, it should not be possible for anyone to dream of wearing a crown. Yet here we are, watching a former president test the limits of a Constitution designed to outlive men like him. The gilded image he projects is not just vanity; it is philosophy. Trump’s self-portrait as sovereign, his promises of retribution and “total authority,” all point to a single conviction: that the republic exists to serve him, not the other way around.

But the Constitution is not a crown to be seized. It is a contract written in defiance of crowns. It does not anoint, it constrains. The founders, imperfect and divided as they were, understood that tyranny rarely begins with conquest; it begins with applause. It begins when citizens grow weary of the slow work of democracy and mistake spectacle for strength.

Trump’s stagecraft, his golden halls, his loyal courtiers; these are not signs of power. They are the trappings of insecurity, ornaments worn by a man who confuses obedience with respect. Every king eventually learns that crowns are heavy not because they are precious, but because they are hollow. The weight comes from fear – fear of exposure, fear of accountability, fear that the illusion will fail.

Whether the American experiment survives this chapter will depend on who the nation decides to be: spectators or citizens, courtiers or guardians. The choice is not his to make. The framers left the throne empty for a reason. The people were meant to occupy it: collectively, imperfectly, endlessly arguing but never bowing. That is the quiet revolution the founders entrusted to us, and it is still the only one worth defending.

So when a man stands before a crowd and declares himself a king, the proper answer is the same now as it was in 1776: we have no sovereign here. Only a Constitution. Only a people. And that must always be enough.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.20.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.