To reach this elevated status became more and more challenging as the Middle Ages wore on.

By Mark Cartwright

Historian

Introduction

Knights were the most-feared and best-protected warriors on the medieval battlefield, while off it, they were amongst the most fashionably dressed and best-mannered members of society. To reach this elevated status, however, became more and more challenging as the Middle Ages wore on. Requirements included an aristocratic birth, training from childhood, money for weapons, horses and squires, and a knowledge of the rules of chivalry. Good looks, fine clothes, a striking coat of arms, and an ability to recite poetry and songs were optional but highly desirable extras if one wanted to rise to the very top of this elite level of medieval society.

How to Become a Knight

The process of becoming a knight started from early childhood. The typical starting point for a young lad of 7 to 10 years old was to become a page when he learned to handle horses, hunt, and use mock weapons while serving a knight proper. From age 14, the next step was to become a squire (or esquire), who had more responsibility than a page, learned to use real weapons, and started an education, especially the study of chivalry. Squires assisted knights in peace and war, holding their extra lances or shield, cleaning their armour, and looking after the several horses each knight owned. If all went well, the youth, by then around 18 years old, was made a knight in a ceremony known as a dubbing.

For a dubbing, a soon-to-be knight had a good bath and kept a church vigil overnight. On the day of the ceremony the squire was dressed by two knights with a white tunic and white belt to symbolise purity, black or brown stockings to represent the earth to which he will one day return, and a scarlet cloak for the blood he is now ready to spill for his baron, sovereign, and church. He was given his sword back, now blessed by a priest with the proviso he always protect the poor and weak. The blade had two cutting edges – one to represent justice, the other loyalty and chivalry.

The knight awarding the honour then might attach a spur or put the sword and belt on the squire, and give him a kiss on the cheek. The squire was then knighted by a simple tap on the shoulders or neck with the hand or sword, or even a heavy blow (colée or ‘accolade’) – meant to be the last one he should ever take without retaliating and to remind him of his obligations and moral duty not to disgrace the man who dealt the blow. Next, he was given his horse, and then his shield and banner, which might bear his family coat of arms. The ceremony was rounded off by a large feast.

Early knights could come from any background, all that was needed was courage and endeavour. Many early knights were given their title on the battlefield by a lord or monarch (often symbolically in the form of spurs, hence the expression ‘to win one’s spurs’) typically after displaying particular valour and effectiveness in fighting the enemy. By the 13th century CE, though, most knights were sons of knights as the class sought to maintain its exclusivity in society.

Weapons and Armor

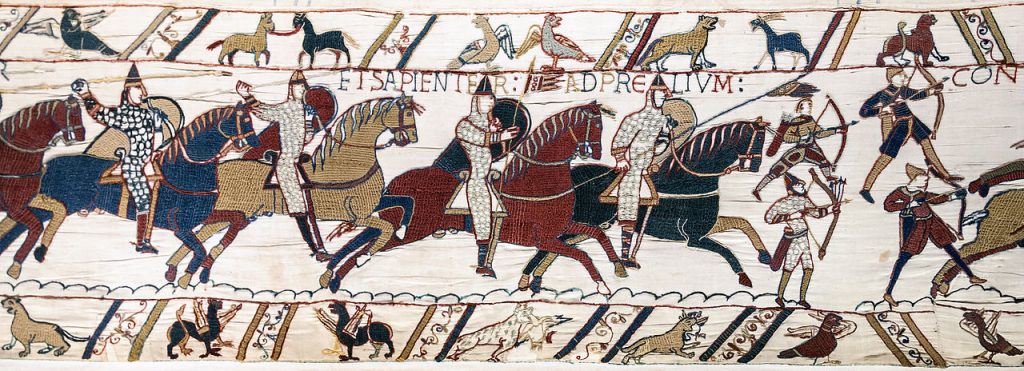

A knight had to be accomplished in riding a horse while carrying a long, triangular leather and wood shield and a wooden lance 2.4-3.0 metres (8-10 ft) in length, so he needed to practise guiding his steed using only the knees and feet. He must be capable of using a heavy sword with a blade up to one metre (40 inches) in length for a sustained period of fighting and fit enough to move around with speed while wearing heavy metal armour. A proficiency with additional weapons such as a dagger, battleaxe, mace, bow, and crossbow might come in handy, too.

A knight’s armour was, from the 9th century CE, of chain mail made up of small interconnected iron rings. A hooded coat, trousers, gloves, and shoes could all be made from mail and so cover the entire body of the knight except the face. A full suit of mail could weigh up to 13.5 kilograms (30 pounds). Over the top, a sleeveless surcoat was worn, which allowed the knight to show off his family colours or coat of arms.

Plate armour became more common from the 14th century CE and offered better protection against arrows and sword blows. The plates could protect all parts of the body, and they came in various shapes and designs, the pieces held together using laces (points), straps, hinges, buckles, or semicircular rivets. A full suit of armour weighed from 20 to 25 kilograms (45-55 lbs) – less than a modern infantryman would carry in equipment – and so a knight who fell off his horse was not totally helpless and immobile. In any case, knights often mixed mail and plate armour, selecting their own protection according to preference, with chest plates and greaves for the legs being the most common pieces worn.

The head was protected by a helmet or helm as they were often called. First simple conical helmets were worn, then a nose guard or mask was added, and, by the 13th century CE, the fully enclosed helmet was used with further design tweaks such as a protruding snout for better ventilation or conical top to deflect blows better. Hiding the face, a helmet could be personalised to identify who was inside. Punched ventilation holes could provide decorative patterns, many were painted, and plumes of exotic birds could be added to the top. There was even a fashion for three-dimensional figures mounted on the crest which represented anything from stag horns to dragons.

The all-important horses that made knights the equivalent of modern tanks on the medieval battlefield also had particular protection. The simplest option was a cloth caparison which might also enclose the animal’s head and ears and which was another handy canvas for armorial display. Better protection was offered by a two-piece coat of chain mail (one for the front and the other hung behind the saddle), a padded helmet, a plate head covering, or an armour plate of metal or boiled leather to protect the chest.

To use these weapons effectively and get used to wearing a load of metal armour, it was a good idea for a knight to put in a bit of practice before meeting the challenge of actual warfare. There were specific devices for training such as the quintain – a rotating arm with a shield at one end and a weight at the other. A rider had to hit the shield and keep riding on to avoid being hit in the back by the weight as it swung around. Another device was a suspended ring which had to be removed using the tip of the lance. Riding a horse at full gallop and cutting at a pell or wooden post with one’s sword was another common training technique. All of these skills helped the knight fulfil their primary functions as bodyguards to nobles, as members of a garrison guarding a castle, or on the battlefield as the elite element of a medieval army. Some knights operated as independent mercenaries and, for the more adventurous and pious, there was always the opportunity presented by the crusades which punctuated the frequent European secular wars of the Middle Ages. For the really devout Christian knight, there was also the option of joining a military order such as the Knights Hospitaller or Knights Templar, where one lived much like a monk but at least had the opportunity of the best training and weapons of all medieval knights.

Jousting and Tournaments

When not on active military duty, a knight could keep their weapons and horse riding skills sharp by practising in tournaments. These competitions took two formats, either a mêlée which was a mock cavalry battle where knights had to capture each other for a ransom or the joust where a single rider armed with a lance charged at an opponent who was similarly armed. The knights protected themselves with a shield and full armour which was often specialised for jousting so that the face and arms were better protected but mobility was compromised. The knights rode towards each other at full gallop along a 100-200 metre (110-220 yards) long area known as the lists with the aim of knocking the opponent off his horse. To minimise the risk of injury (but certainly not eliminate it), weapons were adapted such as the fitting of a three-pointed head to the lance in order to reduce the impact and swords were blunted (rebated).

There were even opportunities to dress up and do the whole thing in fancy dress, most often as knights of the Round Table or figures from ancient mythology. As there were local aristocratic ladies present, tournaments were also a chance to display some chivalry. Tournaments became such prestigious events with prizes for the winners that knights began to practise for them in earnest and circuits developed with many knights becoming, in effect, professional tournament players.

Clothes

Knights were amongst the most dedicated of all medieval fashion followers, indeed, other professions such as the clergy were often rebuked for trying to make themselves look as flashy as the knights did. Although clothes were not too dissimilar between the classes, those who could afford it tended to wear better quality materials with a much better fit. Tunics (long, short, padded, sleeveless or long-sleeved), stockings, cloaks, gloves, and hats of all shapes and sizes were all worn. In the Middle Ages, clothing was often considered a part of a person’s taxable property; such was its value. In addition, it was very much a status symbol, with certain materials being restricted to the aristocrats by law.

The most common material was wool, but silk, brocade, camel hair, and furs allowed a knight to make a fashion statement. Bright colours were favoured such as crimson, blue, yellow, green, and purple. Individuality was expressed in all the extras that could be added to the basic clothing of the day such as metal pieces, gold and silver stitching, buttons, jewels, glass cabochons, feathers, and fine embroidery. Belt buckles and brooches to tie a cloak at the shoulder were an especially popular way of showing off a bit of bling. All in all, then, with flamboyant taste and both the means and right to wear the full range of the medieval wardrobe, a knight was easily spotted when walking down the street.

Leisure Pursuits

The most common leisure activity for knights was hunting. Beaters and dog handlers stalked the animals in the local forest or a protected deer park using leashed dogs. When ready a horn was blown to signal the off, and then the nobles rode with a pack of hunting dogs to chase down animals such as deer, boars, wolves, foxes, and hares. Once an animal was cornered, a noble was given the opportunity to make the kill using a lance or bow.

Falconry was another popular pursuit. Without firearms, a falcon was the only way to catch birds which flew beyond the range of an archer, although for the medieval nobility, the whole sport had a mystique and mythology about it beyond the expedience of bagging a few fowl for the table. Popular birds of choice were the gerfalcon, peregrine, goshawk, and sparrowhawk, amongst others, and their typical prey was forest birds but especially cranes and ducks.

As part of the code of medieval chivalry, knights were expected not only to be familiar with poetry but also capable of composing and performing it. Books, really sheaves of illuminated manuscripts, were available on all manner of subjects besides poetry, though. There were books on chivalry, table manners, hunting, stories from ancient Greece, the legends of King Arthur, and biographies of famous knights like Richard I of England (r. 1189-1199 CE) and Sir William Marshal (c. 1146-1219 CE). Finally, there were games such as backgammon, chess, and dice, which might involve betting, all useful to while away the hours on those lengthy castle sieges that characterised medieval warfare.

Chivalry

A knight was expected to be chivalrous at all times. The ethical, religious and social code of chivalry pervaded the upper echelons of medieval society and was made ever more important with an endless stream of romantic literature extolling the virtues of chivalrous conduct. In order to maintain a good reputation and gain favour with those in power, a knight, therefore, needed to display such essential chivalric qualities as courage, military prowess, honour, loyalty, justice, good manners, and generosity – especially to those less fortunate than oneself. If a knight did not do these things and, even worse, if they did the opposite, they could lose their status as a knight and their reputation and that of their family was blackened forever. In such a case, the disgraced knight had his spurs removed, his armour smashed, and his coat of arms removed or thereafter given some shameful symbol or only represented upside down.

Death

When a knight came to the end of his fighting days, it was not uncommon to join a military order and so ensure a nice spot in one of their cemeteries or even churches. Sir William Marshal employed just such a strategy, invested as a Knight Templar at the last minute, he was interred in Temple Church in London where his effigy still rests. Effigies of knights were a common way to ensure remembrance. Typically portrayed in full armour and bearing a shield, these stone carvings can still be seen in many churches across Europe, and they provide historians with an invaluable record of medieval weapons and armour but also remind of the reverence knights enjoyed in the Middle Ages.

Bibliography

- Coss, P. Heraldry, Pageantry and Social Display in Medieval England. (Boydell Press, 2012).

- Gies, J. Life in a Medieval Castle. (Harper Perennial, 2015).

- Gravett, C. English Medieval Knight 1200–1300. (Osprey Publishing, 2002).

- Gravett, C. English Medieval Knight 1300–1400. (Osprey Publishing, 2002).

- Gravett, C. English Medieval Knight 1400–1500. (Osprey Publishing, 2001).

- Gravett, C. Knights at Tournament. (Osprey Publishing, 2018).

- Phillips, C. The Complete Illustrated History of Knights & The Golden Age of Chivalry.(Southwater, 2017).

Originally published by the Ancient History Encyclopedia, 11.07.2018, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.