Language, at its most honest, is a fluid thing. It adapts, it borrows, it evolves. Yet national policy too often treats it like a fortress, with high walls and narrow gates.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

The Unspoken Power of Language in Immigration

It is often said that borders are not just drawn on maps. They are whispered in classrooms, scrawled on official forms, and coded into the language of political debate. When nations debate immigration, they do not only weigh numbers and economics; they craft narratives of belonging, purity, and threat. Few tools have served this story more effectively than language itself.

In the United States and across much of the Western world, policies restricting non-English education, or mandating English-only usage in public services, have emerged under the guise of unity. They are framed as practical, even benevolent. But beneath this rhetoric lies a cultural instinct toward purification, an anxious defense of an imagined core identity. Language becomes less a means of communication than a gatekeeper, deciding who deserves access and who remains an outsider.

While the symbols of nationalism often reside in flags and borders, it is the regulation of speech, the pressure to speak in a certain tongue, that reveals how deeply embedded fears of cultural erosion truly are.

The Rise of English-Only Laws

In the United States, the English-only movement gained steam in the 1980s, spearheaded by groups such as U.S. English and ProEnglish. Advocates argued that promoting a single language would foster national unity and ease the integration of immigrants. The movement culminated in a flurry of state-level legislation: by 2023, over 30 U.S. states had adopted laws declaring English their official language, with varying degrees of enforcement.

These laws, however, are rarely about efficiency. Government agencies in multilingual communities continue to provide translation services. Public schools still encounter students who speak dozens of languages at home. What these laws signal instead is a posture—a symbolic defense of a culture perceived to be under siege.

Critics argue that English-only policies often function as a proxy for anti-immigrant sentiment. They emerge most forcefully during periods of heightened demographic change. For example, the passage of California’s Proposition 227 in 1998, which effectively dismantled bilingual education in the state, followed years of rising Latino immigration and coincided with broader anti-immigrant initiatives like Proposition 187. The language in these campaigns was not subtle. Immigrants were painted as unwilling to assimilate, and English was cast not merely as a tool, but as a test.

Cultural Purity and the Myth of Assimilation

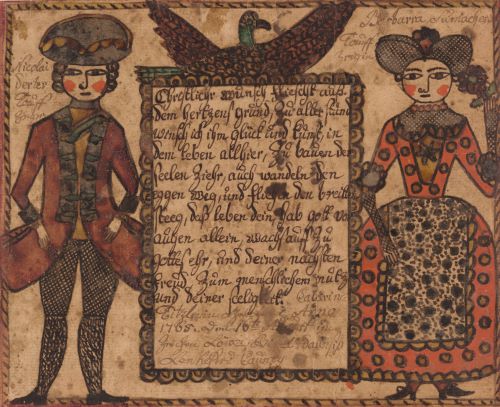

The assumption behind many language laws is that linguistic assimilation equals cultural loyalty. But this notion rests on a selective memory of history. American identity has always been pluralistic. Early German communities in Pennsylvania published newspapers and taught school in their native tongue for decades. French persisted in Louisiana. Native languages, far from being protected, were actively suppressed in boarding schools under federal policy, another grim reminder that language has long been a battlefield for cultural dominance.

The real fear underlying these laws is not that newcomers fail to learn English (most immigrants do, often within a generation) but that they retain something else alongside it. The anxiety centers on the idea that multilingualism dilutes national character. The pressure to speak English “like a native” becomes a pressure to behave, to think, even to identify as someone else entirely.

In this sense, language laws often reveal more about the dominant culture than about those they target. They are less about welcoming immigrants than about controlling how they transform the cultural landscape. Assimilation, then, becomes a one-way street: you may enter, but only if you leave your voice behind.

Education as a Tool of Control

The classroom has long been a crucible where these debates intensify. Bans on non-English instruction have appeared in cycles, usually during periods of national insecurity. During World War I, several states outlawed German-language education. In the Cold War, anxieties about “foreign ideologies” fueled suspicion toward schools that preserved heritage languages.

Modern bilingual programs, despite overwhelming research supporting their cognitive and academic benefits, remain politically vulnerable. Critics claim they isolate students or slow integration, despite evidence that strong bilingual foundations often accelerate second-language acquisition and promote long-term achievement.

What these arguments miss, or deliberately ignore, is that education policy is never just about pedagogy. It is a mirror of the nation’s anxieties. If the language a child speaks at home is viewed as a threat, then what is being defended is not curriculum but culture. A policy banning Spanish-language instruction, for instance, is less a comment on syntax than on the perceived place of Spanish-speaking people in society.

Global Echoes and Historical Parallels

The policing of language in immigration policy is not uniquely American. Across Europe, similar dynamics unfold. France’s policies on laïcité, originally crafted to protect secularism, now extend to linguistic and cultural conformity, with pressure placed on Arabic-speaking immigrants to adopt “neutral” French norms. In the United Kingdom, debates over the supposed erosion of “British values” often latch onto the visibility of foreign languages in public spaces.

Even in nations founded on colonial diversity, such as Canada, the promotion of English (and to a lesser extent French) as a national identity has created tensions with immigrant communities whose native languages are viewed as culturally distant.

Globally, the tension often plays out along racial and religious lines. Language is rarely neutral; it is racialized, politicized, and moralized. A Vietnamese speaker in Texas may be asked to “speak English” with a disapproving glare, while a French tourist receives indulgent curiosity. Who is allowed to have an accent, and who is penalized for it, reveals the deeper architecture of inclusion and exclusion.

Resistance and Reclamation

Despite the institutional forces at play, language can also be a site of resistance. Immigrant communities have long fought to preserve their linguistic heritage, not just as a cultural artifact but as a form of survival. Language ties generations, histories, and traditions. It carries emotion and memory in ways policy cannot fully erase.

Grassroots bilingual education programs, community translation initiatives, and the publication of multilingual literature are all forms of reclaiming space in a culture that too often asks immigrants to disappear. Even within institutions, there are educators and activists working to reverse harmful policies and restore the dignity of multilingual identity.

In recent years, there has been growing recognition of the value of linguistic diversity—not only as a pedagogical asset but as a marker of global competence. Yet this progress remains precarious. For every effort to expand access to multilingual services, there is a political countermove insisting on English-only virtue.

Conclusion: The Accent of Belonging

Language, at its most honest, is a fluid thing. It adapts, it borrows, it evolves. Yet national policy too often treats it like a fortress, with high walls and narrow gates. Immigration, in this context, becomes not only a matter of who gets in, but of who gets to speak, and how.

What is ultimately at stake in these debates is not communication but belonging. When policymakers attempt to restrict language under the banner of unity, they often achieve the opposite. They fracture communities, stigmatize difference, and entrench divisions under the illusion of a common tongue. To recognize this is not to dismiss the value of shared language. Rather, it is to insist that such sharing must be voluntary, mutual, and never used as a cudgel. The future of any pluralistic society lies not in erasing difference, but in learning how to live with it, language and all.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.17.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.