The civil rights movement revealed the limits of American democracy when confronted by its own conscience. It was not solely as a moral victory.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Paradox of Democracy and Control

The American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s has long been celebrated as a triumph of nonviolent resistance against racial oppression, a moral reckoning that forced the nation to confront the gulf between its democratic ideals and its social realities during the civil rights movement. Yet behind the public imagery of disciplined marches and soaring rhetoric lay another history, a history of state repression. At every level of government, law enforcement agencies and intelligence bureaus responded to the movement not with understanding but with hostility. They viewed mass protest not as democratic participation but as disorder, and they met moral resistance with the coercive machinery of law and force.1 From the streets of Birmingham to the offices of the FBI, the state’s instruments of power were mobilized to contain, discredit, and sometimes destroy those who sought racial justice.

Local law enforcement served as the frontline of suppression. In southern cities, sheriffs and police officers became the enforcers of segregationist authority, wielding batons, fire hoses, and attack dogs against demonstrators who refused to yield.2 These actions were often defended under the rhetoric of “law and order,” a phrase that cloaked violence in the language of legality. The televised images of brutality, from Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge to Birmingham’s Kelly Ingram Park, shocked global audiences but revealed a deeper truth: that the state’s commitment to maintaining public order often outweighed its commitment to protecting human rights.3 The spectacle of American police attacking peaceful citizens seeking enfranchisement undercut the nation’s self-presentation as the leader of the “free world” at the height of the Cold War.

This pattern of repression was not confined to local policing. As demonstrations spread and the movement grew more militant, federal and state agencies began to treat domestic dissent as a threat to national security. The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) exemplified this shift. Between 1956 and 1971, the FBI conducted covert operations to infiltrate, surveil, and sabotage civil rights organizations and their leaders.4 Under the direct authority of J. Edgar Hoover, agents wiretapped Martin Luther King Jr., disseminated false information to the press, and sought to sow divisions within the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and later, the Black Panther Party.5 The program blurred the distinction between security and subversion, casting citizens who demanded equality as enemies of the state.

At the same time, the civil rights movement coincided with the rise of militarized policing in the United States. Spurred by urban unrest and shaped by Cold War counterinsurgency doctrines, police departments began adopting military equipment and tactics for domestic use. The 1967 Detroit uprising and the 1968 Chicago Democratic National Convention illustrated the convergence of military and police power: tear gas, armored vehicles, and tactical formations deployed not against invading armies but against American citizens.6 In both northern and southern contexts, the escalation of force reinforced the message that the state reserved the right to define protest as rebellion and dissent as disorder. This transformation foreshadowed a new era in which the maintenance of social control would increasingly rely on militarized policing rather than mediation.

The government’s dual strategy, visible violence and covert surveillance, exposed the fragility of American democracy when challenged from below. What emerged was a paradox: a liberal democratic state that justified repression in the name of freedom.7 Officials who invoked the Constitution to defend segregation, or national security to justify surveillance, revealed that power in America was not neutral but racialized. The civil rights movement thus became a mirror through which the nation saw its own contradictions. The struggle for equality was never merely against prejudice; it was against the state’s monopoly on legitimacy, a system that used law, intelligence, and violence to preserve a racial order under the guise of legality. This essay examines how that system operated: through local police brutality, military tactics, federal intelligence programs, and the collaboration of white supremacist actors shielded by the state. The result is a portrait of repression that forces reconsideration of what it means to defend democracy in a nation that so often confuses authority with justice.

The Local Front: Police Brutality and the Politics of Law and Order

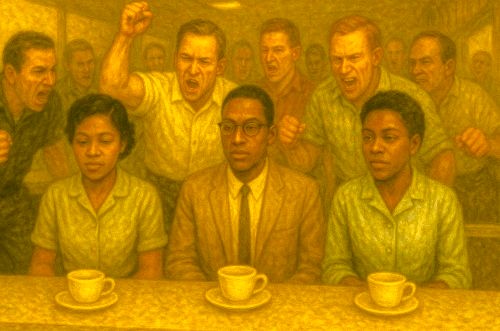

The most immediate and visible expression of state repression during the civil rights movement came from local police forces. Across the South, sheriffs and city police acted as guardians of the racial status quo, wielding the power of the state to maintain segregation and silence dissent.8 In Birmingham, Alabama, Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor became the national face of such enforcement. During the 1963 campaign led by Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Connor’s forces unleashed fire hoses and police dogs on unarmed demonstrators, including children, in an attempt to crush the movement through fear.9 His actions were not the product of individual cruelty alone but reflected a systemic understanding of law enforcement as a tool of racial order. By invoking “law and order,” Connor claimed legal legitimacy while using violence to suppress justice itself.

These displays of brutality were not isolated incidents but part of a coordinated regional strategy. In Jackson, Mississippi, the police routinely arrested protesters for violating “breach of peace” statutes whenever they attempted to integrate public spaces.10 In Albany, Georgia, mass arrests were used to overwhelm the movement without overt bloodshed, revealing a subtler form of repression: bureaucratic suffocation.11 And in Selma, Alabama, Sheriff Jim Clark turned Dallas County into a police fortress, using cattle prods and nightsticks against marchers attempting to exercise their right to vote. The infamous events of “Bloody Sunday” on March 7, 1965, when state troopers and deputies attacked demonstrators on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, became a defining image of the civil rights era, a tableau of democratic hypocrisy.12

Local police actions often worked in tandem with state governments that framed protest as criminality. Southern politicians such as Alabama Governor George Wallace and Mississippi’s Ross Barnett manipulated the rhetoric of “law and order” to equate civil disobedience with anarchy.13 This framing inverted moral responsibility: violence by the state was portrayed as preservation of order, while nonviolent protest was treated as provocation. The discourse proved powerful beyond the South. By the late 1960s, “law and order” had become a national political slogan, one that shifted public attention from racial injustice to fears of social instability.14 In this sense, the southern police crackdown functioned as both a literal and rhetorical template for the nationalization of repression.

The complicity of federal officials further enabled these abuses. Although President Kennedy and Attorney General Robert Kennedy publicly condemned southern violence, they were often hesitant to intervene directly for fear of alienating white southern voters.15 Federal marshals were dispatched selectively, and prosecutions of police misconduct remained rare. The Justice Department’s 1965 investigation of Selma documented systematic violations of civil rights but resulted in limited accountability.16 This federal ambivalence reinforced the perception among southern officials that violence against protesters would go unpunished. The message was unmistakable: while Washington denounced segregation in principle, it tolerated repression in practice.

Yet the local repression of civil rights activism had unintended consequences. Television and press coverage of police violence generated national outrage and transformed public opinion. Images of children being attacked by police dogs or clubbed on the Edmund Pettus Bridge shattered the myth of southern paternalism and forced the federal government to act.17 The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 owed as much to the courage of demonstrators as to the brutality of those who tried to silence them. Still, even these legislative victories could not erase the structural lesson the movement revealed: that American law enforcement was not a neutral arbiter of order but an instrument of political power. The civil rights era exposed the extent to which the state, at its most local level, could transform the language of law into a weapon of oppression.18

Militarization of Policing: Crowd Control and Urban Warfare

The civil rights era coincided with a profound transformation in American policing: the gradual militarization of domestic law enforcement. The shift was neither abrupt nor accidental. It developed through federal policy, Cold War ideology, and responses to civil unrest that blurred the line between public safety and internal warfare.19 By the mid-1960s, police departments across the country were experimenting with military-style tactics, acquiring surplus weaponry, and receiving federal training in riot control. Although these measures were justified as necessary to maintain peace, they marked the emergence of a policing philosophy that viewed citizens, especially Black citizens, as potential insurgents.20

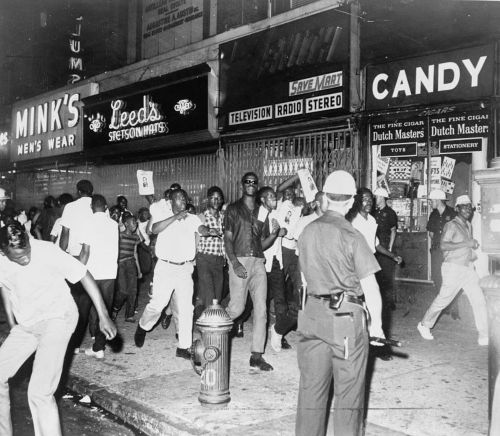

This transformation accelerated after the 1964 Harlem uprising and the wave of urban rebellions that followed in Watts, Newark, and Detroit.21 In each case, the official response emphasized control rather than reform. Police and National Guard units patrolled streets in armored vehicles, imposed curfews, and deployed tear gas and live ammunition.22 The Kerner Commission, established by President Lyndon Johnson in 1967 to investigate the causes of these uprisings, concluded that the excessive use of police force had often been the spark that ignited violence.23 Yet even as the Commission warned that America was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white, separate and unequal,” federal policy shifted toward strengthening law enforcement rather than addressing inequality.24 The paradox was clear: the state responded to racial unrest not by alleviating injustice but by upgrading its arsenal.

In 1968, the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) was created as part of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act, channeling unprecedented federal funds into local police departments.25 The LEAA financed riot gear, communications systems, and new training programs modeled on military doctrine. Police commanders attended seminars led by military officers who framed domestic disorder as a form of insurgency requiring counterinsurgency methods.26 Manuals such as the U.S. Army Field Manual FM 19-15, Civil Disturbances and Disasters provided guidance on crowd control, area denial, and coordinated use of force.27 Through these programs, the federal government institutionalized militarized policing under the pretext of efficiency, transforming local police into semi-military forces equipped and trained for confrontation rather than mediation.

Nowhere was this militarization more visible than during the 1967 Detroit uprising, one of the largest and most destructive urban revolts in American history. Over five days, police and National Guard units killed forty-three people, most of them African Americans, and arrested thousands.28 Armored personnel carriers rolled through residential neighborhoods, and tanks were deployed under the justification of restoring order. Eyewitness accounts and later government investigations revealed widespread abuses, including warrantless searches, indiscriminate gunfire, and the use of excessive force against unarmed civilians.29 Rather than a law enforcement operation, Detroit resembled a battlefield, an image that symbolized the convergence of racial control and militarized state power.

The same logic guided the response to the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, where police confronted antiwar and civil rights demonstrators with tear gas and baton charges.30 The violence, broadcast on national television, shocked the public, prompting the Walker Report to describe it as a “police riot.”31 Yet rather than diminish police authority, the incident reinforced political demands for tougher measures against dissent. Politicians from both parties increasingly associated civil unrest with moral decay, adopting a vocabulary of containment that justified the use of overwhelming force.32 The language of “riot control” merged with the rhetoric of “law and order,” creating a national consensus that equated safety with subjugation.

By the decade’s end, the civil rights movement’s moral appeal had been overshadowed by a new paradigm of governance, one defined by surveillance, militarization, and the criminalization of protest.33 The expansion of police power during this period laid the foundation for the modern carceral state. It also revealed how the machinery of repression, once assembled, could outlive the movements it was designed to suppress. The tools developed to quell marches in Selma and uprisings in Detroit would later be used in the “war on drugs” and the “war on terror.”34 In this sense, the militarization of policing during the civil rights era was not merely a reaction to unrest; it was the beginning of a permanent transformation in the American state, one that redefined citizenship itself as a condition subject to control.35

State Complicity and the White Mob: Segregationist Governments and the Politics of Inaction

While militarized policing represented one face of repression, another emerged from deliberate state complicity with white supremacist violence. In many parts of the South, segregationist officials did not simply fail to protect civil rights demonstrators; they often facilitated, coordinated, or passively sanctioned attacks upon them.36 Law enforcement officers frequently operated as agents of racial order, allowing white mobs to assault protestors with impunity. The pretense of “maintaining peace” became an alibi for maintaining segregation. When violence erupted, southern governors and police chiefs routinely framed it as spontaneous racial unrest rather than as the predictable outcome of state-sponsored terror.37

One of the clearest examples of such complicity occurred during the Freedom Rides of 1961, organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to test desegregation rulings in interstate travel. In Anniston, Alabama, a Greyhound bus carrying activists was attacked by a mob that smashed its windows, slashed its tires, and firebombed it as law enforcement stood aside.38 In Birmingham, Commissioner Connor deliberately withdrew police protection for fifteen minutes, allowing a mob of Ku Klux Klan members to beat riders with pipes and chains.39 Federal investigators later confirmed that the Birmingham Police Department had coordinated with the Klan in advance.40 The episode revealed not only the brutality of local racism but the willingness of government officials to weaponize inaction. Their silence was strategic; by withholding protection, they encouraged violence while maintaining plausible deniability.

The same pattern recurred throughout the decade. In Jackson, Mississippi, police looked away as white mobs attacked Freedom Riders in bus terminals and on courthouse steps.41 In Mississippi’s Neshoba County, three civil rights workers (James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner) were abducted and murdered in 1964, with the involvement of deputy sheriff Cecil Price, who arrested them on fabricated charges before releasing them to waiting Klansmen.42 The FBI investigation, codenamed “MIBURN” (for Mississippi Burning), exposed a local network of white supremacists embedded within law enforcement.43 Although federal prosecutors eventually secured convictions, the murders underscored a systemic failure: when the law itself became the accomplice, justice ceased to exist. This alliance between state power and racist violence revealed that the civil rights struggle was not simply against prejudice but against an entire political system designed to preserve racial dominance through selective enforcement of the law.

Federal response to these atrocities remained hesitant. President Kennedy, while privately enraged by the Freedom Riders’ treatment, prioritized political stability over confrontation with southern officials.44 The Department of Justice sought injunctions and negotiated “cooling-off” periods rather than pursuing aggressive prosecutions. Even President Johnson’s later interventions, such as the deployment of federal troops to protect marchers in Selma, occurred only under overwhelming public pressure.45 By the time of the 1964 Democratic National Convention, southern delegations that openly supported segregation still exercised enormous influence within the party. The federal government’s half-hearted enforcement of civil rights thus reflected a larger truth: America’s institutions, from the courthouse to the Capitol, were deeply entangled in the very injustices they claimed to oppose. In this moral inversion, the state became both enforcer and bystander, a power that punished protest while protecting oppression.46

Surveillance and Sabotage: COINTELPRO and Federal Intelligence Operations

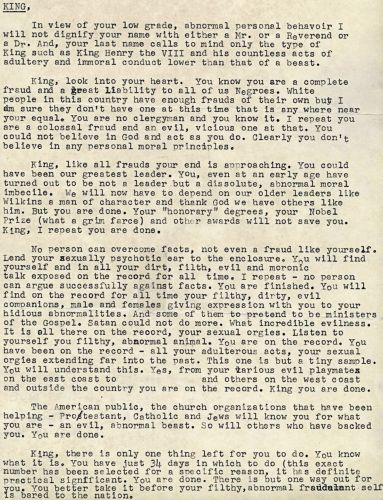

If local law enforcement represented the visible arm of repression, COINTELPRO embodied its invisible counterpart. The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Counterintelligence Program, active from 1956 to 1971, was conceived under the direction of J. Edgar Hoover as a covert campaign to monitor, infiltrate, and neutralize domestic organizations deemed subversive.47 While initially aimed at Communist Party operatives, by the 1960s the program’s primary targets were civil rights leaders and Black liberation groups. Under the guise of protecting national security, COINTELPRO blurred the line between intelligence work and political warfare, deploying psychological tactics to discredit and destabilize movements seeking racial justice.48

The Bureau’s obsession with Martin Luther King Jr. typified the program’s racialized logic. Hoover regarded King as both a moral threat and a potential Communist sympathizer.49 FBI agents wiretapped King’s phones, bugged his hotel rooms, and sent him anonymous letters threatening to expose alleged indiscretions unless he abandoned public life.50 Internal memoranda described the goal as preventing the rise of a “Black Messiah” capable of unifying the movement.51 This campaign of intimidation went far beyond intelligence gathering, it was a deliberate attempt to erode King’s credibility, undermine his alliances, and psychologically exhaust him. The strategy revealed the federal government’s capacity to weaponize surveillance not for protection but for political containment.

COINTELPRO’s reach extended well beyond King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and later the Black Panther Party became primary targets.52 Agents infiltrated meetings, planted false information, and forged letters to create distrust among members. In some cases, they incited rival groups to violence, then used the resulting chaos as justification for arrests and raids.53 The FBI’s infiltration of the Black Panthers was particularly destructive. Through operations like “COINTELPRO–Black Nationalist Hate Groups,” the Bureau sought to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, and otherwise neutralize” the Panthers by framing them as violent extremists.54 Agents circulated fabricated pamphlets and press releases, fueling public fear and legitimizing lethal police actions such as the 1969 raid that killed Fred Hampton in Chicago.55

Although the Bureau justified these operations as national security measures, subsequent investigations revealed a pattern of systematic illegality.56 The 1976 Church Committee Report, established by the U.S. Senate to investigate intelligence abuses, found that the FBI had conducted hundreds of unauthorized break-ins, mail openings, and electronic surveillances against American citizens.57 These activities violated both constitutional protections and the Bureau’s own charter. Yet Hoover’s long tenure and political influence had shielded the FBI from oversight. Presidents and legislators alike feared confronting him, and so the agency operated as a state within the state, an unelected institution exercising unchecked power over democratic life.

The exposure of COINTELPRO forced a national reckoning. For many Americans, the revelation that their government had targeted civil rights leaders as enemies rather than heroes undermined the moral legitimacy of the state.58 It also illuminated the broader architecture of repression: a feedback loop in which protest generated surveillance, surveillance justified militarization, and militarization produced further protest. By the time COINTELPRO was formally dismantled in 1971, its legacy had already seeped into the foundations of American governance.59 The state had learned to disguise coercion behind legality, to pursue subversion not through open violence but through secrecy. In that transformation, the meaning of citizenship itself shifted, from the right to dissent to the condition of being watched.60

The Politics of Provocation: Misinformation, Infiltration, and Manufactured Violence

The covert operations of COINTELPRO did not merely collect intelligence; they created it. Beyond surveillance, federal and local agencies engaged in provocation and misinformation, deliberately manipulating civil rights and Black liberation movements to generate the very disorder they later cited as justification for repression.61 By planting false narratives, inciting conflict among activists, and fostering conditions for violence, the government blurred the line between law enforcement and political sabotage. These acts of deception exposed how far the state was willing to go to preserve the appearance of order, even at the cost of truth.

The Black Panther Party became a primary target of these tactics. Beginning in 1967, the FBI and local police departments infiltrated Panther chapters across the country, often using paid informants who acted as provocateurs.62 Internal FBI memos revealed strategies to “create factionalism” by spreading forged letters accusing leaders of embezzlement, betrayal, or sexual misconduct.63 In Los Angeles, Chicago, and Oakland, agents deliberately heightened tensions between the Panthers and rival Black nationalist groups, sometimes provoking deadly confrontations.64 One infamous example involved fabricated correspondence suggesting that the Panthers planned to assassinate members of the United Slaves (US) organization in Los Angeles, an operation that contributed to the murders of Panthers John Huggins and Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter in 1969.65 These manipulations transformed the FBI from an observer of unrest into an architect of it.

Local police, emboldened by federal rhetoric, adopted similar tactics. City and state intelligence units collaborated with the FBI in creating “red squads” that tracked activists and maintained secret files on thousands of citizens.66 In Chicago, the Chicago Police Department’s Red Squad worked alongside the FBI to infiltrate both civil rights and antiwar organizations.67 Informants routinely provoked confrontations that allowed police to justify raids and arrests. The 1969 police raid on the apartment of Panther leader Fred Hampton, coordinated by the FBI and Chicago police, demonstrated how provocation could escalate to state-sanctioned execution.68 Internal documents later revealed that the FBI informant William O’Neal had supplied a floor plan of Hampton’s apartment and drugged him the night of the raid, ensuring his death as he slept.69

The use of misinformation extended beyond infiltration to media manipulation. The FBI’s “neutralization” campaigns relied on strategic leaks to journalists, designed to portray civil rights groups as violent radicals or foreign puppets.70 False reports claiming that King and his associates were influenced by Communists circulated widely in mainstream newspapers, while government press releases framed Black Power organizations as existential threats to national stability.71 These tactics exploited Cold War anxieties and racial fears, shifting public perception of the movement from one of moral urgency to one of criminal menace. The media thus became an unwitting partner in the government’s campaign to delegitimize dissent.

Some intelligence reports also suggest that federal agents actively encouraged violence to justify repression.72 The Church Committee documented multiple instances in which informants supplied weapons or urged activists toward violent action, only for those acts to be used as evidence of subversive intent.73 Similar tactics appeared in state-level surveillance programs, particularly in California and New York, where police intelligence divisions staged or facilitated illegal acts to create grounds for arrests.74 The logic was circular: state agents produced the violence that their superiors then condemned as proof of the need for more policing. By transforming protest into a controlled theater of disorder, the government sustained its claim to moral authority even as it undermined its democratic legitimacy.

The politics of provocation revealed a deeper continuity between overt violence and covert manipulation. Whether through the firehoses of Birmingham or the false letters of COINTELPRO, the goal remained the same, to fracture movements, discredit their leaders, and preserve the racial and political hierarchy.75 In both visible and hidden forms, repression functioned as performance: law enforcement created the crisis it promised to contain. The exposure of these operations in the 1970s confirmed what activists had long suspected, that the American state’s commitment to democracy ended where its control was threatened.76 The civil rights era thus stands not only as a story of liberation but as a warning of how easily a democracy can descend into surveillance and deceit when the defense of order becomes indistinguishable from the exercise of power.77

Conclusion: Democracy Under Surveillance

The civil rights movement revealed the limits of American democracy when confronted by its own conscience. From the sidewalks of Birmingham to the corridors of the FBI, the state’s response to nonviolent protest exposed a government that equated order with obedience and dissent with disorder.78 The images of police brutality that shocked the world were not aberrations but expressions of a political system that had long relied on violence to preserve racial hierarchy. As federal and local authorities joined forces to suppress protest through militarization, infiltration, and misinformation, they demonstrated how deeply racism had been institutionalized as a form of governance. The civil rights struggle thus forced the United States to confront a question it has never fully resolved: can a democracy dedicated to liberty survive when it turns its power inward against those who demand it?

The deployment of state power against civil rights activists was not simply an abuse of authority; it was an extension of a national logic that privileged security over freedom.79 The same bureaucratic justifications that sanctioned fire hoses in Birmingham later sanctioned wiretaps in Washington and armored vehicles in Detroit. In every case, repression was rationalized as protection, a defense of public safety or national integrity. Yet what the state called stability was, in practice, the preservation of inequality. The language of “law and order” masked a deeper disorder, the moral collapse of institutions unable to distinguish justice from control. Through this inversion, the government redefined the pursuit of equality as an existential threat and recast those seeking reform as enemies of the public peace.

Even after the formal end of COINTELPRO and the passage of civil rights legislation, the legacy of repression endured. The militarization of policing expanded through the “war on crime,” the “war on drugs,” and later the “war on terror,” all rooted in the same logic of containment that governed the 1960s.80 Surveillance technologies grew more sophisticated, while the structural conditions that had produced rebellion (poverty, segregation, and racialized policing) remained unresolved. Contemporary movements such as Black Lives Matter have inherited not only the moral tradition of the civil rights struggle but also the apparatus of repression built to destroy it. The continuity is unmistakable: the state continues to respond to the demand for justice with the reflex of control.81

To understand the civil rights movement solely as a moral victory is to overlook the deeper warning it offers. The movement’s triumphs (the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, the dismantling of Jim Crow) were achieved despite the state, not because of it.82 Behind every legislative success lay the shadow of surveillance, violence, and deceit. The history of this era teaches that democracy’s greatest threat arises not from the streets but from the institutions sworn to defend it. The civil rights movement, in exposing that truth, did more than transform American law; it revealed the moral cost of a nation that could only acknowledge justice after first trying to suppress it.83

Appendix

Footnotes

- Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–63 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988), 247–250.

- Diane McWhorter, Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama—The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 132–135.

- Justice Department Report on Law Enforcement in Selma, Alabama (Washington, DC: Department of Justice, 1965), 14–17.

- U.S. Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, Final Report (“Church Committee Report”), Book III (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1976), 5–6.

- David J. Garrow, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (New York: William Morrow, 1986), 412–415.

- National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (“Kerner Commission Report”) (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968), 120–125.

- Elizabeth Hinton, America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s (New York: Liveright, 2021), 42–46.

- Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 108–111.

- McWhorter, Carry Me Home, 132–136.

- John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 162–165.

- Branch, Parting the Waters, 555–559.

- Justice Department Report on Law Enforcement in Selma, Alabama, 12–15.

- George C. Wallace, “Inaugural Address,” January 14, 1963, Alabama Department of Archives and History.

- Michael W. Flamm, Law and Order: Street Crime, Civil Unrest, and the Crisis of Liberalism in the 1960s (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 22–25.

- Nick Bryant, The Bystander: John F. Kennedy and the Struggle for Black Equality (New York: Basic Books, 2006), 167–172.

- Justice Department Report on Law Enforcement in Selma, Alabama, 25–28.

- Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff, The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation (New York: Vintage, 2006), 249–253.

- Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 49–52.

- Kristian Williams, Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America (Brooklyn: Soft Skull Press, 2004), 95–99.

- Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime, 71–74.

- Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989), 12–15.

- Kerner Commission Report, 65–69.

- Kerner Commission Report, 98–101.

- Kerner Commission Report, 1.

- Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, Pub. L. No. 90–351, 82 Stat. 197 (1968).

- Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime, 85–88.

- U.S. Army Field Manual FM 19-15: Civil Disturbances and Disasters (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1968).

- Fine, Violence in the Model City, 203–208.

- Fine, Violence in the Model City, 250–255.

- Frank Kusch, Battleground Chicago: The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention (New York: Praeger, 2004), 42–46.

- Rights in Conflict: The Official Report of the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1968), 6.

- Flamm, Law and Order, 121–124.

- Hinton, America on Fire, 52–54.

- Naomi Murakawa, The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 35–38.

- Alex S. Vitale, The End of Policing (London: Verso, 2017), 63–66.

- Dittmer, Local People, 142–146.

- Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981), 59–61.

- FBI Report on the Freedom Rides Violence, 1961, National Archives, Washington, DC.

- McWhorter, Carry Me Home, 209–211.

- U.S. Senate Committee on Government Operations, Investigation of the Freedom Rides Violence, 87th Congress, 1961.

- Roberts and Klibanoff, The Race Beat, 137–141.

- U.S. v. Cecil Price et al., 383 U.S. 787 (1966); Department of Justice Civil Rights Division Files, NARA, Mississippi Burning Case.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “MIBURN” Case File, 1964, National Archives, Jackson Field Office.

- Bryant, The Bystander, 224–227.

- Taylor Branch, Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963–65 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998), 564–567.

- Carol Anderson, Eyes Off the Prize: The United Nations and the African American Struggle for Human Rights, 1944–1955 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 210–212.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Counterintelligence Program: Internal Security—Black Nationalist Hate Groups,” Memorandum, August 25, 1967, National Archives, Washington, DC.

- Athan Theoharis, The FBI and American Democracy: A Brief Critical History (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004), 88–91.

- Garrow, Bearing the Cross, 407–409.

- FBI Memorandum, “King–Communist Influence,” October 1963, in Church Committee Report, Book III (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1976), 191–193.

- FBI Memorandum, “Prevent the Rise of a ‘Black Messiah,’” March 4, 1968, in Church Committee Report, Book III, 200.

- Carson, In Struggle, 152–155.

- Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall, Agents of Repression: The FBI’s Secret Wars Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement (Boston: South End Press, 1988), 78–81.

- FBI COINTELPRO Files, “Black Nationalist Hate Groups,” 1967–1971, National Archives.

- Betty Medsger, The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI (New York: Knopf, 2014), 245–249.

- Kenneth O’Reilly, Racial Matters: The FBI’s Secret File on Black America, 1960–1972 (New York: Free Press, 1989), 301–304.

- Church Committee Report, Book III, 8–9.

- David Cunningham, There’s Something Happening Here: The New Left, the Klan, and FBI Counterintelligence (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 222–225.

- Theoharis, The FBI and American Democracy, 111–113.

- Hinton, America on Fire, 60–63.

- O’Reilly, Racial Matters, 211–214.

- Churchill and Vander Wall, Agents of Repression, 65–68.

- FBI Memorandum, “Counterintelligence Program—Black Nationalist Hate Groups,” March 1968, National Archives.

- Medsger, The Burglary, 233–235.

- Church Committee Report, Book III, 205–208.

- Frank Donner, Protectors of Privilege: Red Squads and Police Repression in Urban America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 141–144.

- Donner, Protectors of Privilege, 159–162.

- Jeffrey Haas, The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2010), 87–93.

- FBI Internal Report on William O’Neal’s Role in the Hampton Raid, 1970, National Archives, Washington, DC.

- O’Reilly, Racial Matters, 220–224.

- Cunningham, There’s Something Happening Here, 228–230.

- Church Committee Report, Book III, 221–223.

- Church Committee Report, Book III, 226–228.

- Donner, Protectors of Privilege, 172–175.

- Hinton, America on Fire, 85–89.

- Athan Theoharis, The FBI and American Democracy: A Brief Critical History (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004), 120–122.

- Williams, Our Enemies in Blue, 188–191.

- Branch, Pillar of Fire, 610–613.

- Carol Anderson, White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide (New York: Bloomsbury, 2016), 103–107.

- Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime, 183–188.

- Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2010), 222–226.

- Dittmer, Local People, 378–381.

- Hinton, America on Fire, 266–269.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press, 2010.

- Anderson, Carol. Eyes Off the Prize: The United Nations and the African American Struggle for Human Rights, 1944–1955. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ———. White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide. New York: Bloomsbury, 2016.

- Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–63. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988.

- ———. Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963–65. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998.

- Bryant, Nick. The Bystander: John F. Kennedy and the Struggle for Black Equality. New York: Basic Books, 2006.

- Carson, Clayborne. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Churchill, Ward, and Jim Vander Wall. Agents of Repression: The FBI’s Secret Wars Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement. Boston: South End Press, 1988.

- Cunningham, David. There’s Something Happening Here: The New Left, the Klan, and FBI Counterintelligence. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

- Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

- Donner, Frank. Protectors of Privilege: Red Squads and Police Repression in Urban America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- Fine, Sidney. Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989.

- Flamm, Michael W. Law and Order: Street Crime, Civil Unrest, and the Crisis of Liberalism in the 1960s. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

- Garrow, David J. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. New York: William Morrow, 1986.

- Kusch, Frank. Battleground Chicago: The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention. New York: Praeger, 2004.

- Haas, Jeffrey. The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2010.

- Hinton, Elizabeth. America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s. New York: Liveright, 2021.

- ———. From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Kerner Commission. Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968.

- McWhorter, Diane. Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama—The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001.

- Medsger, Betty. The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI. New York: Knopf, 2014.

- Murakawa, Naomi. The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- O’Reilly, Kenneth. Racial Matters: The FBI’s Secret File on Black America, 1960–1972. New York: Free Press, 1989.

- Payne, Charles. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

- Roberts, Gene, and Hank Klibanoff. The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation. New York: Vintage, 2006.

- Theoharis, Athan. The FBI and American Democracy: A Brief Critical History. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

- United States Army. Field Manual FM 19-15: Civil Disturbances and Disasters. Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1968.

- United States Department of Justice. Report on Law Enforcement in Selma, Alabama. Washington, DC: Department of Justice, 1965.

- United States Federal Bureau of Investigation. Counterintelligence Program: Internal Security—Black Nationalist Hate Groups. Memorandum, August 25, 1967. National Archives, Washington, DC.

- ———. “MIBURN” Case File (Mississippi Burning). National Archives, Jackson Field Office, 1964.

- ———. Internal Report on William O’Neal’s Role in the Hampton Raid. National Archives, Washington, DC, 1970.

- United States Senate. Rights in Conflict: The Official Report of the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968.

- ———. Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities (Church Committee Report). Book III. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976.

- ———. U.S. Senate Committee on Government Operations, Investigation of the Freedom Rides Violence. 87th Congress, 1961.

- Vitale, Alex S. The End of Policing. London: Verso, 2017.

- Wallace, George C. “Inaugural Address.” January 14, 1963. Alabama Department of Archives and History.

- Williams, Kristian. Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America. Brooklyn: Soft Skull Press, 2004.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.10.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.