The persistent portrayal of Ottoman governance as religious coercion reveals the extent to which fear shaped external interpretation.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Pluralism Misread as Threat

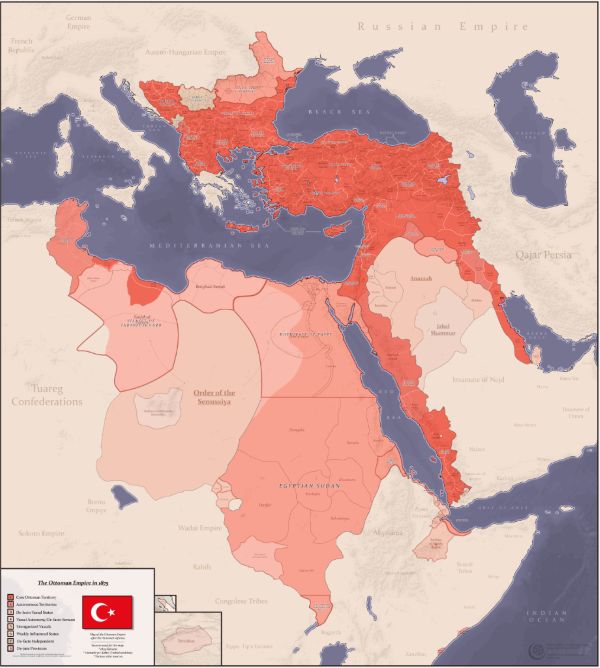

From the fifteenth through the nineteenth centuries, the Ottoman Empire governed a vast and religiously diverse population through a legal order that deliberately separated political sovereignty from confessional law. Muslims, Christians, and Jews lived under the same imperial authority while regulating personal matters through their own religious courts. This arrangement was not informal tolerance or ad hoc compromise, but structured governance embedded in imperial administration. The millet system institutionalized legal pluralism, allowing distinct communities to preserve religious law, family practice, and communal regulation without imposing them on others. Far from undermining stability, this system enabled the empire to govern territories stretching across southeastern Europe, Anatolia, the Levant, and North Africa for centuries without demanding legal uniformity as a condition of loyalty.

Yet from the perspective of many European observers, Ottoman pluralism appeared not as accommodation but as domination. Christian diplomats, travelers, missionaries, and later historians frequently described the empire as ruled by Islamic law imposed upon unwilling subjects. These accounts portrayed the presence of Sharia as evidence of coercion rather than as a bounded legal system explicitly limited to Muslims. The fact that Christian and Jewish courts operated openly, continuously, and with recognized jurisdiction was often ignored or dismissed. Difference itself was taken as proof of oppression, and pluralism was reframed as takeover.

This misreading reflected deeper assumptions about law and sovereignty in European political thought. In emerging early modern and modern European states, law was increasingly understood as a uniform expression of state authority, binding all subjects equally and signaling political belonging. A system in which different communities lived under different laws appeared incoherent, backward, or dangerous. Observers accustomed to legal uniformity interpreted Ottoman pluralism through their own conceptual frameworks, projecting fears of religious domination onto an imperial system that operated according to fundamentally different principles.

The myth of “forced Sharia” arose not from Ottoman practice but from external anxiety about pluralism itself. The Ottoman legal order limited religious law by design, confining its reach to voluntary confessional domains while preserving imperial sovereignty above them. Islamic law did not expand outward to subsume Christian or Jewish communities, nor did it function as an instrument of conversion or legal conquest. European critics, unable or unwilling to recognize this distinction, transformed coexistence into threat. By examining the millet system as it functioned internally and contrasting it with its portrayal abroad, this demonstrates how outsiders often invent religious danger where pluralism actually exists, revealing more about the fears of the observer than about the society being judged.

The Ottoman Legal Order: Sovereignty without Uniformity

The Ottoman Empire developed a legal order that deliberately disentangled political sovereignty from legal uniformity. Authority resided unequivocally in the sultan and the imperial administration, yet this authority did not require the imposition of a single legal system upon all subjects. Governance operated through layered jurisdictions that distinguished between imperial power, administrative regulation, and confessional law. This separation allowed the state to assert control over territory, taxation, and security while permitting diverse communities to regulate their internal affairs according to inherited norms without threatening imperial cohesion.

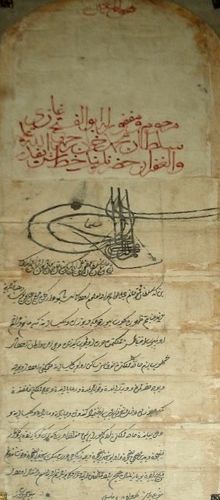

Central to this arrangement was the distinction between kanun and Sharia, a division that structured Ottoman governance at every level. Kanun, the body of sultanic administrative and fiscal regulations, applied across the empire regardless of religion or communal affiliation. It governed taxation, land tenure, military service, commercial regulation, and public order. Sharia, by contrast, functioned as a religious legal system primarily applicable to Muslims in matters of personal status, ritual obligation, and moral conduct. The coexistence of these legal domains was not accidental but foundational. By allowing kanun to assert imperial authority while confining Sharia to its proper confessional scope, the Ottomans preserved political unity without demanding religious or legal sameness.

This structure reflected a deeply pragmatic understanding of empire and its limits. The Ottomans inherited territories with long-established legal traditions, including Byzantine Christian law, multiple Islamic schools of jurisprudence, Jewish communal law, and a wide array of local customary practices. Rather than dismantling these traditions, imperial governance incorporated them into a broader framework of control that prioritized continuity over disruption. Local courts continued to function, communal authorities retained jurisdiction over personal matters, and legal languages familiar to subject populations remained in use. This approach minimized resistance and preserved social order by reassuring communities that imperial rule would not overturn the legal foundations of daily life. Uniform law was neither necessary nor desirable for maintaining authority over an empire whose strength depended on managing diversity rather than erasing it.

Sovereignty in the Ottoman system did not depend on exclusive legal authorship or the monopolization of normative authority. The state did not need to be the sole source of law in order to be the ultimate source of power. Authority was expressed through protection, taxation, military capacity, and the adjudication of disputes that crossed communal boundaries. Legal plurality was not merely tolerated but operationalized as a governing principle, enabling the state to rule effectively over populations with different moral and legal expectations. This conception stood in sharp contrast to emerging European models of the state, which increasingly equated political unity with legal uniformity and treated multiplicity as a sign of weakness or fragmentation. Ottoman governance accepted multiplicity as compatible with loyalty, provided imperial supremacy remained uncontested.

The role of the sultan as guarantor rather than comprehensive legislator further illustrates this distinction. The ruler was responsible for maintaining order, ensuring justice, and protecting communities under imperial rule, not for enforcing a single moral or religious code across the population. Legal diversity was managed, regulated, and bounded rather than eradicated. State intervention occurred primarily when disputes crossed confessional lines, threatened fiscal order, or endangered public stability. Internal legal difference, so long as it remained within recognized limits and did not challenge imperial authority, was not treated as political defiance.

Understanding Ottoman sovereignty without uniformity is essential to evaluating later accusations of religious domination. The empire did not govern by extending Islamic law outward to absorb Christian or Jewish communities. Instead, it governed by containing legal difference within a stable political framework that prioritized loyalty over conformity. What appeared to European observers as incoherence or weakness was, in practice, a durable system that balanced authority and autonomy. The Ottoman legal order demonstrates that sovereignty does not require sameness, and that pluralism can function as an instrument of stability rather than a symptom of disorder.

The Millet System as Formalized Legal Pluralism

The millet system represented the Ottoman Empire’s most explicit and enduring institutionalization of legal and religious pluralism. Rather than treating diversity as an administrative inconvenience or a temporary concession, the Ottoman state formally recognized distinct religious communities as corporate bodies with defined legal authority over internal affairs. These communities, known as millets, were organized primarily along confessional lines and granted responsibility for regulating matters of personal status, religious practice, education, and communal discipline. The system did not emerge fully formed at a single moment, nor was it the product of abstract theory. It developed gradually as a practical solution to governing a heterogeneous empire whose stability depended on managing difference rather than erasing it.

Each millet functioned as a semi-autonomous legal community under imperial sovereignty. Muslim, Greek Orthodox, Armenian, Jewish, and later Catholic and Protestant communities maintained their own courts, clerical hierarchies, and legal traditions. These institutions adjudicated marriage, divorce, inheritance, and internal disputes according to religious law. Crucially, this authority was explicitly limited. Millets did not legislate for the empire at large, nor did they exercise coercive power beyond their own members. The boundaries of jurisdiction were well understood and carefully maintained.

The Ottoman state did not view this arrangement as a dilution of authority, but as an extension of effective governance. By delegating internal regulation to recognized communal leaders, the empire strengthened its capacity to rule over vast and diverse populations. Religious authorities acted as intermediaries between the state and their communities, responsible for tax collection, social discipline, and the maintenance of order. This delegation reduced administrative strain on imperial institutions and localized potential sources of conflict. Far from undermining sovereignty, the millet system allowed the state to project authority without imposing intrusive uniformity, reinforcing loyalty through recognition rather than coercion.

Legal pluralism under the millet system was not chaotic or informal. Jurisdictional boundaries were enforced through imperial courts, and disputes that crossed communal lines were adjudicated by state authorities. Individuals could not impose their religious law on others, and no millet possessed authority over another. The system was designed to prevent precisely the kind of legal takeover that later European critics imagined. Law functioned as a boundary marker rather than a weapon of domination.

Participation in a millet’s legal system was not always rigid or compulsory. In practice, individuals sometimes chose to bring cases before imperial courts rather than communal ones, particularly in commercial or intercommunal disputes. This flexibility underscores the pragmatic nature of Ottoman pluralism. Legal systems coexisted not as sealed compartments but as coordinated jurisdictions within a shared political framework. The state remained the ultimate arbiter, ensuring that pluralism did not fragment sovereignty.

The millet system demonstrates that religious legal diversity can be formalized without threatening political unity. Far from representing Islamic domination over minorities, it institutionalized restraint by explicitly limiting the reach of religious law and preventing cross-imposition. Its longevity across centuries and regions testifies to its effectiveness as a governing structure. What later observers would describe as religious coercion was, in practice, a carefully managed pluralism that allowed difference to persist without becoming conflict. The millet system stands as a historical example of law functioning not as a tool of takeover, but as a mechanism for containing diversity within a stable imperial order.

Jewish and Christian Courts under Ottoman Rule

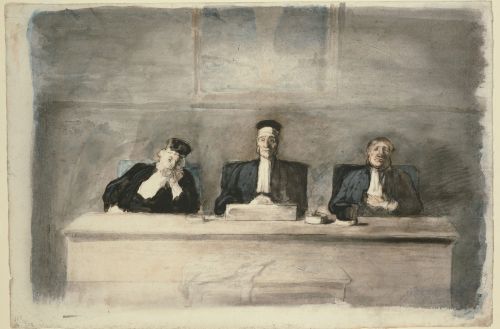

Jewish and Christian courts operated as integral and enduring components of the Ottoman legal landscape, exercising recognized authority over the internal affairs of their respective communities for centuries. These courts were not clandestine, marginal, or provisional institutions, but publicly acknowledged bodies whose jurisdiction was defined, regulated, and protected by imperial policy. Rabbis, bishops, priests, and other communal authorities presided over cases involving marriage, divorce, inheritance, education, charity, and communal discipline, applying religious law to members of their own confessions. Their authority did not exist in tension with the state, but within a framework explicitly sanctioned by imperial governance, which regarded internal self-regulation as a stabilizing force rather than a political liability.

The functioning of these courts illustrates the firm and deliberate limits placed on religious law within the Ottoman system. Jewish batei din and Christian ecclesiastical courts possessed no jurisdiction over Muslims or over members of other confessional communities. They could not compel participation outside their own populations, nor could they impose judgments on those who did not voluntarily submit to their authority. Even within their communities, enforcement relied largely on social compliance and communal obligation rather than independent coercive power. Where enforcement required escalation, it was mediated through imperial authorities, ensuring that religious law remained subordinate to state sovereignty and confined to its proper domain.

Ottoman subjects were not rigidly confined to confessional courts in all matters. In cases involving commerce, property disputes across religious lines, or appeals against communal authority, Jews and Christians frequently turned to imperial courts. These courts applied kanun and administrative law rather than religious doctrine, offering a neutral forum recognized by all communities. The availability of this alternative underscores the flexibility of the Ottoman system and contradicts portrayals of minorities trapped under oppressive religious jurisdictions.

The coexistence of religious and imperial courts produced a layered legal environment rather than a fragmented one. Jurisdiction was determined by the nature of the dispute rather than by an absolute hierarchy of law. This allowed individuals to navigate legal options pragmatically while preserving communal autonomy. Far from undermining order, this system reduced conflict by clarifying boundaries and providing multiple avenues for dispute resolution. Legal pluralism functioned as coordination, not competition.

The sustained operation of Jewish and Christian courts across centuries offers some of the clearest evidence against claims of religious legal domination in the Ottoman Empire. These institutions endured precisely because they remained confined to internal communal matters and respected the limits of their jurisdiction. Their visibility, regularity, and imperial recognition undermine narratives of forced Islamization or imposed Sharia. In practice, Ottoman governance maintained coexistence by ensuring that no religious law crossed the boundary into coercion. The persistence of these courts stands as concrete proof that pluralism under Ottoman rule was not merely tolerated in theory, but actively structured and preserved in practice.

Sharia’s Explicit Limits

Sharia within the Ottoman Empire functioned as a confessional legal system with clearly defined boundaries, not as a universal code imposed upon all subjects. Islamic law applied primarily to Muslims and governed matters such as personal status, ritual obligation, and moral conduct within the Muslim community. It did not claim jurisdiction over Christians or Jews in their internal affairs, nor was it designed to replace or override their religious legal traditions. This limitation was not a concession forced upon Islamic law by circumstance, but a doctrinal feature embedded in classical Islamic jurisprudence.

Ottoman jurists consistently recognized the legal distinction between Muslims and non-Muslims as a foundational principle of governance. Non-Muslim subjects, classified as dhimmis, were understood to live under the protection of the Islamic state while retaining their own religious laws for personal and communal matters. Sharia explicitly acknowledged the legitimacy of Jewish and Christian courts in areas such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, and internal discipline. These courts were not tolerated grudgingly or temporarily, but recognized as lawful institutions operating within a broader Islamic political order. Religious difference was placed within a stable legal framework rather than treated as an anomaly to be eradicated or absorbed.

The role of Islamic courts further underscores these limits in practice. Muslim judges, or qadis, presided primarily over cases involving Muslims and over disputes that crossed communal boundaries when imperial adjudication was required. Even in such cases, judges often relied on administrative law, contractual norms, or imperial regulation rather than imposing Islamic religious doctrine on non-Muslim litigants. The presence of non-Muslims in Islamic courts did not signal the expansion of Sharia’s jurisdiction, but rather the operation of the court as an imperial institution capable of resolving intercommunal disputes. Sharia did not expand opportunistically into domains already governed by communal law. Instead, it functioned alongside other legal systems, constrained by jurisprudential doctrine, custom, and state policy.

Understanding Sharia’s explicit limits is essential to dismantling the myth of forced religious law. The Ottoman state did not use Islamic law as an instrument of cultural conquest or legal homogenization. Its authority rested on administration, taxation, and sovereignty, not on universal religious enforcement. The persistence of Christian and Jewish legal systems within the empire demonstrates that Sharia operated as one legal system among several, not as an imperial weapon. Where later observers imagined domination, the historical record reveals restraint by design.

European Misreadings and the Myth of Religious Takeover

European interpretations of Ottoman legal pluralism were shaped less by observation than by inherited assumptions about law, religion, and sovereignty. From the late medieval period into the nineteenth century, European political thought increasingly equated legitimate rule with legal uniformity and confessional dominance. A state that permitted multiple legal systems to operate openly within its borders appeared incoherent or dangerously permissive. When European observers encountered the Ottoman Empire, they filtered its institutions through these expectations, mistaking difference for disorder and plurality for coercion.

Travel narratives, diplomatic reports, and missionary accounts frequently portrayed Ottoman governance as a system in which Islamic law dominated all subjects regardless of belief. The visible presence of Sharia courts was taken as proof that Muslims ruled by imposing religious norms on Christians and Jews, even when no such imposition occurred. These accounts routinely omitted or minimized the parallel operation of Christian and Jewish courts, despite their public recognition and long-standing activity. Where non-Muslim legal autonomy could not be ignored, it was often reframed as superficial tolerance masking deeper coercion. Pluralism was interpreted not on its own terms, but through a presumption that religious difference must signal domination.

This misreading intensified during periods of geopolitical rivalry and imperial decline. As European powers contested Ottoman territory and influence, representations of Ottoman governance increasingly served polemical and strategic ends. Casting the empire as a regime of religious tyranny provided moral justification for intervention, colonization, and so-called civilizing missions. The myth of forced Sharia functioned as a legitimizing narrative, allowing European actors to frame conquest as liberation. In this context, legal pluralism was no longer merely misunderstood. It was actively inverted into evidence of oppression in order to support expansionist ambitions.

Orientalist scholarship further entrenched these distortions by treating Islamic law as inherently totalizing and incompatible with plural society. Legal restraint, jurisdictional limitation, and confessional boundaries were downplayed in favor of abstract claims about Islamic despotism. The complexity of Ottoman legal practice was flattened into caricature. In this framework, any visible role for Islamic law signaled domination, regardless of how narrowly that law was applied or how effectively it was bounded by imperial administration.

The persistence of this myth also reflected European anxieties about religious difference closer to home. As European states struggled with confessional conflict, minority governance, and the relationship between church and state, the Ottoman example challenged emerging norms of uniform sovereignty. Rather than confronting that challenge directly, observers externalized their fears. What appeared threatening abroad often mirrored unresolved tensions within Europe itself. The Ottoman Empire became a screen onto which Europeans projected concerns about law, faith, and political control.

By conflating pluralism with coercion, European commentators obscured the actual functioning of Ottoman governance and replaced institutional analysis with moralized narrative. The myth of religious takeover endured not because it accurately described Ottoman practice, but because it aligned with European expectations about sovereignty and served political interests. It simplified a complex legal order into a cautionary tale about religious power and civilizational danger. In doing so, it revealed far more about the fears, assumptions, and ambitions of its authors than about the society they claimed to describe. The durability of this myth demonstrates how easily coexistence can be recast as threat when difference is interpreted through anxiety rather than through the realities of law and governance.

Pluralism in Practice versus Fear in Theory

The contrast between how legal pluralism functioned within the Ottoman Empire and how it was imagined by external critics reveals a fundamental gap between institutional reality and ideological interpretation. In practice, pluralism was not an abstract ideal but a daily administrative condition. Communities governed themselves through recognized courts, paid taxes, resolved disputes, and interacted with imperial authority in predictable ways. Law structured coexistence rather than undermining it. Stability emerged not despite difference, but through its regulation.

Ottoman pluralism worked because it treated law as jurisdictional rather than universal. Religious legal systems were confined to personal and communal matters, while imperial authority governed territory, security, taxation, and intercommunal relations. This division reduced friction by preventing legal overreach. Muslims were not subjected to Christian law, Christians were not governed by Jewish courts, and non-Muslims were not compelled to live under Islamic religious doctrine. Coexistence rested on boundaries that were understood, enforced, and largely respected by both communities and the state.

Fear, by contrast, operated in the realm of theory rather than experience. European critiques of Ottoman governance often assumed that the presence of multiple legal systems necessarily implied hierarchy, domination, or coercion. These assumptions were rarely grounded in close observation of how disputes were actually resolved or how communities navigated everyday life under Ottoman rule. Instead, pluralism was judged against European ideals of uniform sovereignty and centralized legal authority that had emerged from specific historical struggles within Europe itself. Where Ottoman governance diverged from those ideals, it was interpreted not as alternative order but as evidence of latent tyranny, even in the absence of coercive practice.

This divergence between practice and perception highlights the power of conceptual frameworks in shaping political judgment. Observers trained to equate legitimacy with uniform law found it difficult to recognize legitimacy expressed through managed diversity and bounded jurisdiction. Ottoman pluralism challenged the assumption that law must be singular in order to be authoritative or just. Rather than reconsider that assumption, critics recast pluralism as disorder, weakness, or threat. Fear filled the explanatory gap created by unfamiliar institutional arrangements, allowing difference to be interpreted as danger rather than as governance operating according to a different logic.

The endurance of the Ottoman system underscores the weakness of fear-based interpretations. For centuries, pluralism functioned not as a source of instability, but as a mechanism of imperial longevity. Legal difference did not fracture the state, provoke constant rebellion, or collapse into chaos. Instead, it allowed diverse populations to coexist under a shared political framework that prioritized loyalty over uniformity. The contrast between this lived reality and the theoretical fear projected onto it demonstrates how easily pluralism can be misjudged when difference is read through anxiety rather than through evidence.

Conclusion: Outsiders Invent Religious Threat Where Pluralism Exists

The Ottoman millet system demonstrates that religious legal pluralism can function as a durable mode of governance rather than as a precursor to domination. For centuries, the empire maintained political authority while permitting Muslims, Christians, and Jews to live under their own religious laws in clearly bounded domains. Law did not operate as an instrument of takeover, nor did any community possess the power to impose its norms on others. Sovereignty was preserved through administration, taxation, and loyalty, not through legal uniformity. The success of this system challenges the assumption that pluralism inevitably undermines political order.

The persistent portrayal of Ottoman governance as religious coercion reveals the extent to which fear shaped external interpretation. European observers, conditioned by emerging ideals of uniform sovereignty and confessional homogeneity, struggled to comprehend a state that governed through managed difference. Rather than recognizing pluralism as an alternative institutional logic, they recast it as evidence of oppression. Islamic law was imagined as expansive and invasive precisely because its limits contradicted European expectations about how law and power should operate together.

This pattern of misreading mirrors earlier and later historical cases in which minority or plural legal systems were framed as threats despite their internal restraint. As with Achaemenid Persia, medieval Jewish communities, or the Ottoman millets, the accusation was rarely that foreign law was actually imposed. It was that difference itself endured. The persistence of distinct legal identities unsettled observers who equated legitimacy with sameness. Fear filled the gap between unfamiliar practice and familiar theory, transforming coexistence into imagined danger.

The Ottoman case offers a broader lesson about the politics of interpretation. Societies often invent religious threat where pluralism exists not because that pluralism fails, but because it exposes the contingency of their own assumptions. When law operates without takeover and authority without uniformity, it challenges deeply held beliefs about power and belonging. In such moments, anxiety is redirected outward. Outsiders do not merely misunderstand pluralism. They recast it as menace in order to preserve the comfort of their own conceptual frameworks. In doing so, they reveal that the fear of religious law often says more about the accuser than about the society being judged.

Bibliography

- Abu Jaber, Kamel S. “The Millet System in the Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Empire.” The Muslim World 57:3 (1967), 212-223.

- Al Tarawneh, Fatima Salim. “The Ottoman Status Quo Regime and the Christian Sects in Jerusalem in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 6:6 (2019), 177-183.

- Barkey, Karen and George Gavrilis. “The Ottoman Millet System: Non-Territorial Autonomy and its Contemporary Legacy.” Ethnopolitics 15:1 (2016), 24-42.

- Braude, Benjamin, and Bernard Lewis, eds. Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire: The Functioning of a Plural Society. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1982.

- Cohen, Amnon. “The Ottoman Approach to Christians and Christianity in Sixteenth‐Century Jerusalem.” Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 7:2 (1996), 205-212.

- Gerber, Haim. State, Society, and Law in Islam: Ottoman Law in Comparative Perspective. Albany: SUNY Press, 1994.

- Greene, Molly. A Shared World: Christians and Muslims in the Early Modern Mediterranean. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Hallaq, Wael B. The Impossible State: Islam, Politics, and Modernity’s Moral Predicament. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

- —-. An Introduction to Islamic Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- İnalcık, Halil. The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age, 1300–1600. London: Phoenix, 1973.

- Masters, Bruce. Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Arab World: The Roots of Sectarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

- Samet, Hadar Feldman. “Cultural Renewal in Early Modern Ottoman Jewish Life.” European Journal of Jewish Studies 19:2 (2025), 189-220.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.13.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.