The lie detector is not a machine of truth but of anxiety. It arises from a fear that speech is untrustworthy, that reason can be manipulated, and that only the body remains innocent.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Truth, Flesh, and the Illusion of Precision

The desire to see truth on the face, to measure deception in the pulse, and to expose moral fault through the body’s involuntary language is not new. Long before the polygraph entered the American courtroom or the security office, early modern and nineteenth-century thinkers pursued the elusive dream of automatic sincerity. The project was not born of technological triumph, but of a deeper philosophical tension: if reason could reveal natural law, could reason also compel the body to confess?

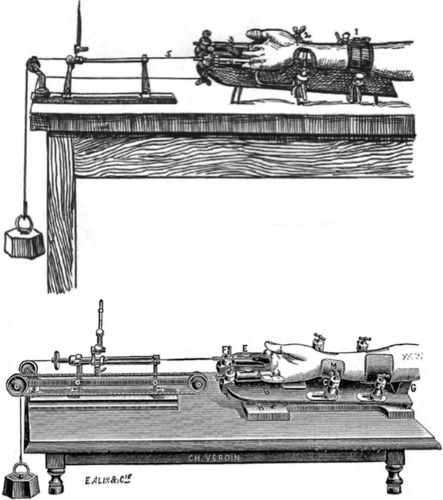

The period between the late eighteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed an evolving set of experiments that sought to mechanize moral knowledge. Physiognomy, plethysmography, and blood pressure tests all emerged not merely from scientific curiosity, but from a cultural fixation with truthfulness as something measurable. Each device and theory – whether Angelo Mosso’s plethysmograph in the 1870s, Cesare Lombroso’s hydrosphygmograph in the 1890s, or William Moulton Marston’s systolic blood pressure test in the 1910s – revealed as much about the anxieties of their age as about the supposed liars they intended to expose.

This essay examines the layered history of early lie detection as a story not of linear progress, but of epistemological fascination. These instruments were not simply forensics tools. They were mirrors held up to a society increasingly desperate to automate morality.

The Legacy of “Moral Physiognomy”: Faces, Fictions, and Frames

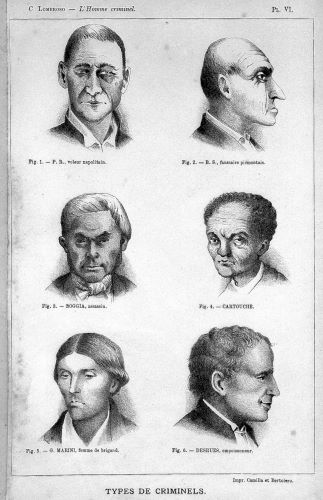

The foundational impulse behind all lie detection technologies can be traced to physiognomy. Popularized by Johann Kaspar Lavater in the late eighteenth century, physiognomy claimed that moral character could be discerned from facial features. Lavater’s work was not merely pseudoscientific curiosity; it reflected Enlightenment efforts to rationalize the soul through the body.1

In Lavater’s schema, the forehead bespoke intellect, the nose temperament, and the eyes the heart. Artists, criminologists, and jurists alike seized upon his illustrations. To the physiognomist, the liar’s face was not a surface but a symptom. The idea that the truth could be read, rather than spoken, reframed perception itself into an act of forensic scrutiny.

“Moral physiognomy” thus created the precondition for later mechanized attempts at lie detection. If moral traits could be observed, surely they could also be measured. What Lavater did with pen and pencil, later scientists sought to do with valves, tubes, and electric currents.

Angelo Mosso and the Weight of the Truth

In the 1870s, Italian physiologist Angelo Mosso developed the plethysmograph, an instrument that measured changes in blood volume by detecting subtle variations in limb swelling and heart rate. Mosso’s work initially focused on fear and intellectual effort. He placed subjects on a delicately balanced table and recorded their physiological reactions to stimuli, including emotionally charged questions.2

What Mosso believed he had uncovered was the signature of guilt. The heart, in its pulsing protest, betrayed the secrets of the mind. Mosso’s table became, in effect, an altar of judgment. The plethysmograph did not detect lies directly. Rather, it recorded arousal, an emotional disturbance that might accompany deceit.

Mosso’s contribution was methodological rather than juridical. His machine remained in the laboratory. Yet the conceptual move it introduced, that the body could unwittingly testify against itself, was profound. For the first time, deception was not merely a moral failing. It became a measurable event, albeit one whose measurement remained contested.

Lombroso’s Hydrosphygmograph and the Criminal Pulse

Cesare Lombroso, often called the father of modern criminology, brought Mosso’s insights into the realm of forensic anthropology. A committed positivist and ardent determinist, Lombroso believed that criminality was rooted in biological degeneracy. His infamous claim that criminals could be identified by physical stigmata placed him squarely in the physiognomic tradition.

In the 1890s, Lombroso developed the hydrosphygmograph, a device that measured blood pressure and pulse fluctuations.3 He used it during interrogations to identify suspects whose physiological responses suggested deception or nervousness. To Lombroso, the body of the criminal was already deviant; the hydrosphygmograph merely confirmed what the eye suspected.

Lombroso’s apparatus was both scientific and theatrical. It turned the interrogation room into a performance space where involuntary signs were elevated above spoken words. Yet the ambiguity of interpretation remained. Was an elevated pulse a sign of lying, or of fear, trauma, or fatigue? Lombroso rarely entertained such questions. His moral categories were fixed, and the machine served them.

William Moulton Marston and the Systolic Judgment

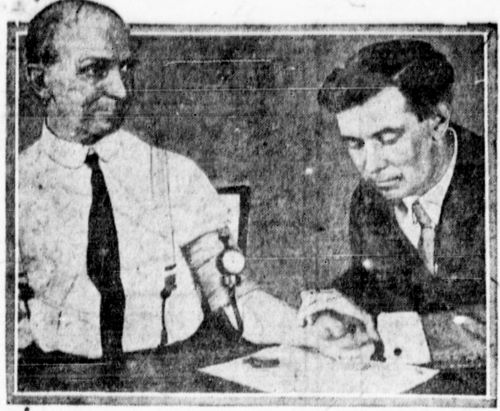

The American psychologist William Moulton Marston approached the problem from a more explicitly legal perspective. In 1915, as a graduate student at Harvard, Marston developed a technique for measuring systolic blood pressure in response to emotionally provocative questioning. He believed that deception produced measurable anxiety, which in turn elevated systolic pressure.4

Marston’s method was more targeted than Mosso’s or Lombroso’s. He aimed not to measure generalized stress, but to identify specific falsehoods through comparative questioning. He referred to his work as a “lie detector,” a term that would soon become synonymous with polygraph technology.

Though Marston’s findings were published in psychological journals, his ambition was to reform legal evidence. He testified in court, advocated for the admissibility of physiological evidence, and even helped inspire the polygraph’s widespread use in police investigations by the 1920s.

Marston’s scientific career later gave way to popular culture. Under the pseudonym Charles Moulton, he created the comic book heroine Wonder Woman, whose Lasso of Truth bore not a little resemblance to the blood pressure cuff.5 The fantasy of compelled confession remained intact, now recast in myth.

From Instruments to Ideologies: Lie Detection and the Culture of Control

What unites these disparate figures – Lavater, Mosso, Lombroso, Marston – is not merely their interest in deceit, but their belief that truth resides outside of language. This belief, once confined to metaphysical speculation, became embodied in wires, cuffs, dials, and charts.

Each device constructed its own moral landscape. In Mosso’s hands, the guilty heart pulsed faster. In Lombroso’s, the deviant physiology betrayed its criminal essence. In Marston’s, the legal system itself was to be reformed by physiology. These machines were not merely tools. They were arguments about guilt, about science, and about who has the right to know.

The drive to locate truth in the body corresponded with broader shifts in surveillance, criminal justice, and bureaucratic rationalization. As the state assumed greater control over its populations, the dream of automatic confession became not only desirable but imperative. Lie detection, in this context, was not merely about catching liars. It was about rendering the subject legible to power.

Conclusion: The Ghost in the Pressure Gauge

The early history of lie detection reveals less about truth than about the desire for certainty. Physiognomy, plethysmography, and blood pressure monitors promised clarity but delivered interpretation. They rendered suspicion scientific, but not necessarily more accurate.

In this sense, the lie detector is not a machine of truth but of anxiety. It arises from a fear that speech is untrustworthy, that reason can be manipulated, and that only the body remains innocent. Yet the body, too, speaks in riddles.

What remains, then, is not a triumph of science over deceit, but a window into the enduring human need to mechanize morality. The instruments may change. The impulse endures.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Johann Kaspar Lavater, Essays on Physiognomy, trans. Thomas Holcroft (London: G.G.J. and J. Robinson, 1789), xiii–xv.

- Angelo Mosso, La Paura (Milan: Treves, 1884), 221–234.Cesare Lombroso, L’uomo delinquente (Turin: Bocca, 1896), 452–460.

- William M. Marston, “Systolic Blood Pressure Symptoms of Deception,” Journal of Experimental Psychology 2, no. 2 (1917): 117–163.

- Jill Lepore, The Secret History of Wonder Woman (New York: Knopf, 2014), 107–118.

Bibliography

- Lavater, Johann Kaspar. Essays on Physiognomy. Translated by Thomas Holcroft. London: G.G.J. and J. Robinson, 1789.

- Lepore, Jill. The Secret History of Wonder Woman. New York: Knopf, 2014.

- Lombroso, Cesare. L’uomo delinquente. Turin: Bocca, 1896.

- Marston, William M. “Systolic Blood Pressure Symptoms of Deception.” Journal of Experimental Psychology 2, no. 2 (1917): 117–163.

- Mosso, Angelo. La Paura. Milan: Treves, 1884.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.