Charlemagne’s reign marked a decisive shift in the relationship between religious authority and political power in medieval Europe.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The coronation of Charlemagne on Christmas Day in the year 800 was a turning point in the political and religious history of medieval Europe. The event placed a Frankish king at the head of a renewed Western Empire and linked his authority to the Roman Church in a way that no earlier early medieval ruler had achieved. Contemporary observers such as Einhard described the ceremony as an unexpected moment, yet the political reality behind it was deeply rooted in the partnership between Charlemagne and Pope Leo III, who sought mutual protection and legitimacy during a period of instability in Rome and the broader Christian world.1

Charlemagne ruled within a long Frankish tradition that viewed kingship as both a military and a sacred vocation. His alliance with the papacy reinforced this vision and helped define a new conception of Christian rulership. The idea that a king acted as God’s representative on earth became a cornerstone of Carolingian political thought, shaping the expectations placed upon rulers and clergy throughout the empire.2 This sacral dimension of rule did not remain symbolic. It became the foundation for a governing structure in which religious conformity, moral discipline, and political loyalty were treated as interconnected obligations.

The term Christendom is often used by historians to describe this political and religious world. Its roots in the Carolingian period were concrete rather than abstract. Charlemagne’s government sought to bind together the peoples of Western Europe under a shared Christian identity enforced by law, ritual, and military power.3 The growing partnership between king and pope, along with the administrative reforms that followed, gave shape to a system in which church and state acted together to direct the moral order of society.

The emergence of this new order did not remain confined to imperial courts or ecclesiastical councils. It had direct and violent consequences for those whom the Carolingian elite viewed as standing outside the Christian community. The Saxon Wars, which spanned more than three decades, revealed the coercive dimensions of Charlemagne’s Christian project. Forced baptisms, destruction of pagan sites, and the creation of laws that made religious noncompliance a capital offense marked these campaigns.4 These measures were justified as acts of moral correction necessary for the stability of the empire and the salvation of its subjects.

Understanding the union of church and state under Charlemagne therefore requires more than a narrative of coronations or reforms. It demands an examination of the ideological world that made coercive Christianization appear not only legitimate but necessary to rulers who believed their authority originated with God. The Carolingian synthesis of political power and religious obligation shaped medieval Europe for centuries and contributed to enduring ideas about the proper relationship between faith and governance. The roots of later Christian imperialism and its modern echoes lie in the structures and assumptions forged during this formative period.

Charlemagne, Papal Legitimacy, and the Construction of Christian Kingship

The alliance between Charlemagne and Pope Leo III took shape during a moment of crisis in Rome. In 799 a faction of Roman nobles attacked Leo, attempted to blind and depose him, and forced him to flee the city. The Royal Frankish Annals record that the pope sought refuge with Charlemagne and appealed for protection.5 The Frankish king recognized the political value of restoring order in Rome, and he escorted Leo back to the city while projecting himself as the defender of the apostolic see. This intervention did not simply resolve a local Roman conflict. It initiated a closer relationship between the Frankish monarchy and the papacy that would culminate in the imperial coronation the following year.

Charlemagne’s position within the Frankish tradition of sacral kingship shaped his response to the Roman crisis. Carolingian scholars and advisers viewed kingship as a divine office in which the ruler acted both as shepherd and judge. Janet Nelson has shown that Charlemagne consciously adopted this role, presenting himself as a ruler responsible for the spiritual and moral welfare of his people.6 This conception drew on older Merovingian precedents but developed further under Charlemagne, particularly through court scholars such as Alcuin, who articulated a Christian vision of kingship grounded in biblical and patristic models. The Frankish king’s authority was therefore understood as both political and sacred.

The coronation in 800 symbolized the consolidation of these ideas. According to Einhard, Charlemagne claimed to be surprised by Pope Leo III’s act of placing the imperial crown upon his head, although Einhard’s narrative likely sought to portray the king as humble rather than as a direct seeker of Roman imperial dignity.7 Regardless of the intended literary image, the ceremony bound Charlemagne’s authority to the institutional prestige of the Roman Church. It offered the pope a powerful protector and gave the Frankish ruler the symbolic mantle of empire, which no Western king had held since the fifth century.

The papacy received tangible benefits from this arrangement. Thomas Noble’s study of the Carolingian papal relationship has shown that the popes of this period relied heavily on Frankish military and diplomatic support to maintain their position within Rome.8 Leo III’s alliance with Charlemagne allowed the papacy to stabilize its authority and assert independence from local Roman factions while embedding itself more deeply in the political culture of the Frankish world. The relationship became reciprocal. The pope consecrated the emperor, and the emperor defended the pope.

This partnership shaped the institutional foundations of medieval Christian rulership. The fusion of Frankish political authority with Roman ecclesiastical legitimacy produced a model in which kingship carried spiritual responsibility and the Church operated as a partner in governance. This synthesis supplied Charlemagne’s rule with a powerful theological framework and laid the groundwork for the wider Carolingian project of creating a unified Christian society governed by divine law and imperial authority.

War, Conversion, and Coercion: The Saxon Wars and the Criminalization of Paganism

The Saxon Wars, which lasted from 772 to 804, formed the most sustained and violent military campaign of Charlemagne’s reign. The Royal Frankish Annals present these conflicts as a necessary defense of Christian order against an unruly pagan people, but modern scholarship has emphasized the political and ideological motivations behind the wars.9 The Saxons were not a unified state but a patchwork of tribes with their own social structures, sanctuaries, and forms of leadership. Their proximity to Frankish territory created persistent conflict over borders and tribute. Charlemagne’s campaigns therefore emerged from a mix of military necessity and the desire to consolidate Frankish control over regions that resisted integration into a Christian political world.

One of the most symbolic acts of the early war was the destruction of the Irminsul in 772. The Annals describe the Irminsul as a major Saxon sacred site and record that Charlemagne’s forces dismantled it shortly after entering Saxon territory.10 This event is often interpreted as a demonstration of Frankish power, but it also represented an early example of Charlemagne’s approach to pagan religion. Destroying the Irminsul was not only an act of military intimidation. It signaled the king’s intention to uproot the spiritual foundations of Saxon society and replace them with Christian forms of worship sanctioned by the Carolingian state. The fusion of political domination with religious reorientation was evident from the outset.

As the wars continued, the Carolingian strategy of forced Christianization emerged more clearly. In 782 a major revolt led by Widukind resulted in the killing of a Frankish force at the Battle of Süntel. Charlemagne responded with the mass execution of 4,500 Saxons at Verden, an event recorded in the Annals without apology or theological justification.11 The massacre has long been debated by historians, but the record demonstrates a governing ideology in which rebellion and paganism were treated as intertwined threats to both the political and spiritual integrity of the empire. Violence became a tool of religious policy as well as imperial control.

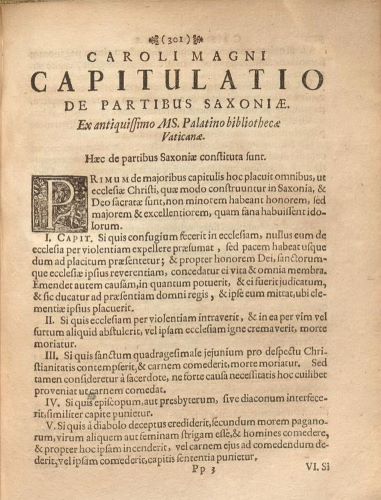

The legal codification of Christian coercion reached its most explicit form in the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae, a set of laws promulgated during the height of the conflict. The text mandates baptism for all Saxons, forbids pagan rituals, and imposes the death penalty for those who refused Christian practices or harmed clergy.12 These provisions were not symbolic measures but enforceable statutes that redefined religious identity as a matter of criminal law. The Capitulatio treated refusal to convert as treason against the empire and an assault upon the Christian order that Charlemagne believed he was divinely appointed to defend.

These laws were part of a broader intellectual and administrative program often described by scholars as Carolingian correctio, or moral correction. This concept referred to the duty of the ruler to guide his people toward proper Christian conduct through legislation, instruction, and punishment. Henry Mayr-Harting and other historians have shown that correctio blended pastoral care with secular authority in ways that made coercion appear both necessary and virtuous.13 Within this framework, forced baptism and capital punishment for pagan practices were interpreted not as abuses of power but as essential steps for creating a stable and morally unified Christian society.

The conclusion of the Saxon Wars in 804 resulted in the full incorporation of Saxon lands into the Carolingian Empire, but the legacy of the conflict extended far beyond military conquest. The campaigns demonstrated how deeply intertwined religious conformity and political obedience had become in Charlemagne’s vision of governance. By criminalizing pagan belief and enforcing Christian identity through law, violence, and administrative reform, the Carolingian state created a model of Christian imperial authority that shaped medieval Europe for generations. The Saxon experience revealed the coercive foundations of early medieval Christendom and the ideological structures that justified the suppression of religious diversity in the name of divine order.

The Institutional Fusion of Church and State under Carolingian Reform

Charlemagne’s efforts to consolidate his rule did not end on the battlefield. They extended into a sweeping program of religious and administrative reform that reshaped the institutional landscape of Western Europe. This program was grounded in the belief that the stability of the empire required uniform Christian practice supported by learned clergy and disciplined lay communities. The Admonitio Generalis of 789 stands as the most comprehensive statement of this vision. It instructed bishops, abbots, and royal officials to enforce Christian teaching, regulate moral behavior, and ensure proper liturgical practice throughout the empire.14 The text blended ecclesiastical directives with civil commands and revealed how thoroughly the Carolingian state relied upon the Church to implement its policies.

Reform began with education. Charlemagne and his advisers believed that the clergy needed improved training in order to guide the people effectively, administer the sacraments correctly, and uphold a coherent Christian identity across vast territories. Rosamond McKitterick has shown that the Carolingian court promoted a revival of learning that reached from cathedrals to monasteries.15 Scriptoria multiplied, biblical texts were recopied with unprecedented accuracy, and scholars such as Alcuin supervised educational reforms that aimed to cultivate a clergy capable of supporting the theological and administrative needs of the empire. This revival strengthened the capacity of the Church to serve as an instrument of state governance.

Liturgical standardization became another major component of Carolingian reform. Charlemagne imported Roman liturgical books and required their use across his domains. The goal was not only to ensure correct worship but also to produce unity in the religious life of the empire. Mayke de Jong has argued that liturgical uniformity helped to create a shared Christian identity that connected local communities to the authority of both king and pope.16 Clergy became responsible for maintaining this unity, and their work increasingly intersected with the political aims of the Carolingian court.

The reforms also reshaped the role of bishops. As the primary administrators of ecclesiastical discipline, bishops gained authority to regulate clerical behavior, oversee monastic communities, and judge cases involving moral or religious offenses. Their pastoral responsibilities were inseparable from their administrative duties. Matthew Innes has shown that bishops became key intermediaries between royal power and local society, interpreting imperial directives and ensuring that Christian norms were upheld.17 Episcopal authority expanded not only through spiritual oversight but also through judicial and administrative functions that reinforced the integration of church and state.

Monasteries played an increasingly important role in this integrated system. Charlemagne required monastic communities to adhere to the Rule of St. Benedict and to maintain internal discipline that reflected the broader moral expectations of the empire. The standardization of monastic life provided the Carolingian state with stable centers of literacy, hospitality, and administrative support. Monasteries also produced the manuscripts that underpinned legal and religious governance, ensuring that imperial commands, liturgical texts, and theological works circulated throughout the empire.

The overall effect of these reforms was to bind ecclesiastical institutions to the machinery of governance. Carolingian kingship could not be separated from the Church, which provided the intellectual, moral, and administrative framework that sustained imperial authority. The ideal of a unified Christian people guided by learned clergy and directed by a divinely appointed ruler became a defining feature of the Carolingian order. This institutional fusion shaped medieval political culture and strengthened the idea that legitimate authority rested upon the harmonization of Christian teaching with secular power.

Christian Imperial Ideology and Its Legacy in Medieval Europe

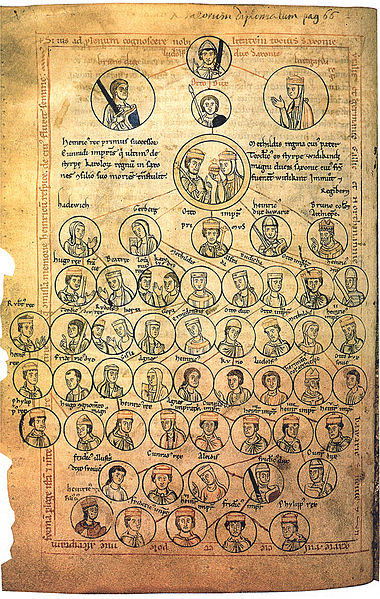

The political and religious structures forged under Charlemagne exerted an influence far beyond his own lifetime. His successors inherited an imperial identity rooted in Christian obligation and moral governance that shaped the political imagination of early medieval Europe. The Ottonian rulers of the tenth century, whom historians often describe as heirs to Carolingian ideology, adopted many of the same principles of sacral kingship. Robert Bartlett has noted that the expectation that kings enforce Christian norms became a central feature of European political culture by the High Middle Ages.18 The Carolingian synthesis of religious and secular authority therefore became a model for how later rulers understood the proper exercise of power.

The memory of Charlemagne himself played a significant role in this development. Hincmar of Rheims, one of the most influential political thinkers of the ninth century, wrote De ordine palatii to outline the principles of court governance. Although the text focuses on the reign of Louis the Pious, it presents Charlemagne as the archetype of a Christian ruler who balanced administrative wisdom with moral leadership.19 Hincmar’s treatise illustrates how Carolingian political theory became a touchstone for subsequent generations of clergy and administrators who sought to define the moral obligations of rulers. Charlemagne’s reign provided both a historical example and a theological framework through which political authority could be evaluated.

The integration of religious responsibility into kingship also shaped medieval responses to perceived threats against Christian unity. Beginning in the eleventh century, both secular rulers and ecclesiastical authorities targeted heretical movements that challenged accepted doctrine or ecclesiastical structure. Scholars such as Giles Constable have shown that these campaigns drew upon earlier assumptions that the ruler must defend Christian society from spiritual danger.20 The Carolingian precedent for coercive religious policy influenced the intellectual justification for suppressing dissent, even as the institutional Church expanded its own mechanisms for enforcing orthodoxy.

The rise of papal authority during the reform movements of the eleventh and twelfth centuries further reflected Carolingian foundations. Thomas Noble has demonstrated that the Carolingian alliance between kings and popes created a new conception of the papacy as a central institution within Christendom.21 The Roman Church’s later claims to universal jurisdiction rested in part on the political elevation it had received during the reign of Charlemagne. Although tensions between papal and imperial authority would eventually erupt into conflicts such as the Investiture Controversy, both sides operated within a framework shaped by the Carolingian model of a unified Christian society governed by divine law.

The Carolingian legacy also extended to cultural and social norms that defined European identity. Bartlett has argued that the spread of Latin Christianity, supported by rulers and clergy, created a shared cultural horizon that distinguished Christian Europe from its neighbors.22 The assumption that legitimate political communities were inherently Christian took firm root during the early medieval period. This idea influenced not only law and governance but also the ways in which medieval Europeans conceptualized religious others, whether pagans, heretics, or non-Christian minorities. The ideological commitment to Christian unity therefore shaped attitudes that endured throughout the Middle Ages.

These developments reveal how the structures established under Charlemagne became foundational for later medieval understandings of power, identity, and religious obligation. The Carolingian fusion of ecclesiastical authority and secular governance helped create a political culture in which religious conformity was treated as essential for social stability. This legacy persisted long after the Carolingian Empire itself fragmented, influencing both institutional practice and the broader intellectual world in which medieval rulers and theologians operated. The idea that the state existed to defend and propagate Christian norms, first articulated and enforced on a large scale in Charlemagne’s reign, continued to shape European history for centuries.

Conclusion

Charlemagne’s reign marked a decisive shift in the relationship between religious authority and political power in medieval Europe. His coronation in 800 symbolized more than a revival of the Western Empire. It formalized a partnership between the Frankish monarchy and the Roman Church that reshaped the governing structures of the early medieval world. By presenting kingship as a sacred vocation and aligning imperial authority with the apostolic prestige of Rome, Charlemagne and Pope Leo III established a model in which religious legitimacy became inseparable from political rule. This synthesis provided the ideological foundation for the Carolingian state and influenced the political thought of subsequent generations.

The enforcement of Christian conformity through military campaigns and legal codes demonstrated the coercive dimensions of this new order. The Saxon Wars revealed the extent to which violence, forced conversion, and the criminalization of pagan practices were incorporated into the formation of a Christian empire. Laws such as the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae defined religious identity as a matter of state jurisdiction and reinterpreted spiritual dissent as a threat to imperial stability. These developments reflected a worldview in which rulers believed they held divine responsibility for the moral condition of their subjects, and in which the boundaries of political community were drawn along religious lines.

The Carolingian reform program further integrated ecclesiastical structures into the administration of the state. Clerical education, liturgical standardization, and episcopal governance created an institutional environment in which the Church operated as both a spiritual and administrative partner in imperial rule. This fusion of ecclesiastical and secular authority established enduring patterns of governance that shaped medieval expectations regarding the duties of rulers and the spiritual mission of political communities. The resulting conception of Christian society, often invoked under the term Christendom, rested on the assumption that the protection and propagation of the faith were central obligations of legitimate rule.

The legacy of Charlemagne’s Christian imperialism endured well beyond the disintegration of his empire. Later medieval rulers, papal reformers, and theologians built upon the structures and principles established during his reign, extending the idea that religious identity defined political order and that rulers bore responsibility for safeguarding Christian unity. These assumptions influenced the suppression of heresy, the expansion of papal authority, and broader notions of European identity. While the modern concept of Christian nationalism does not map directly onto the early medieval world, its ideological roots can be traced to the Carolingian vision of a divinely guided political community. Charlemagne’s reign therefore stands as a formative moment in the long history of Christian political thought and its enduring impact on Western society.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Einhard, Vita Karoli Magni, in Einhard and Notker the Stammerer: Two Lives of Charlemagne, trans. Lewis Thorpe (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969), 65–66.

- Janet L. Nelson, King and Emperor: A New Life of Charlemagne (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019), 112–130.

- Rosamond McKitterick, Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 3–20.

- Royal Frankish Annals, trans. Bernhard Walter Scholz with Barbara Rogers (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1970), 54–70; Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae, in Alfred Boretius, ed., Capitularia Regum Francorum, Vol. 1 (Hanover: Monumenta Germaniae Historica, 1883), 68–70.

- Royal Frankish Annals, 93–95.

- Janet L. Nelson, King and Emperor, 145–172.

- Einhard, Vita Karoli Magni, 65–67.

- Thomas F. X. Noble, The Republic of St. Peter: The Birth of the Papal State, 680–825 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984), 194–210.

- Royal Frankish Annals, 42–50.

- Ibid., 43.

- Ibid., 51–52.

- Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae, in Alfred Boretius, ed., Capitularia Regum Francorum, Vol. 1 (Hanover: Monumenta Germaniae Historica, 1883), 68–70.

- Henry Mayr-Harting, The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England, 3rd ed. (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991), 226–234.

- Admonitio Generalis, in Alfred Boretius, ed., Capitularia Regum Francorum, Vol. 1 (Hanover: Monumenta Germaniae Historica, 1883), 53–62.

- Rosamond McKitterick, The Carolingians and the Written Word (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 97–128.

- Mayke de Jong, The Penitential State: Authority and Atonement in the Age of Louis the Pious, 814–840 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 41–59.

- Matthew Innes, State and Society in the Early Middle Ages: The Middle Rhine Valley, 400–1000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 214–245.

- Robert Bartlett, The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change, 950–1350 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 23–47.

- Hincmar of Rheims, De ordine palatii, in Thomas F. X. Noble, ed., Charlemagne and Louis the Pious: The Lives by Einhard, Notker, Ermoldus and The Astronomer (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009), 223–246.

- Giles Constable, The Reformation of the Twelfth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 115–140.

- Thomas F. X. Noble, The Republic of St. Peter: The Birth of the Papal State, 680–825 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984), 233–250.

- Robert Bartlett, The Making of Europe, 56–85.

Bibliography

- Bartlett, Robert. The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change, 950–1350. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Boretius, Alfred, ed. Capitularia Regum Francorum. Vol. 1. Hanover: Monumenta Germaniae Historica, 1883.

- Constable, Giles. The Reformation of the Twelfth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- De Jong, Mayke. The Penitential State: Authority and Atonement in the Age of Louis the Pious, 814–840. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Einhard. Vita Karoli Magni. In Einhard and Notker the Stammerer: Two Lives of Charlemagne. Translated by Lewis Thorpe. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969.

- Hincmar of Rheims. De ordine palatii. In Charlemagne and Louis the Pious: The Lives by Einhard, Notker, Ermoldus and The Astronomer, edited by Thomas F. X. Noble, 223–246. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009.

- Innes, Matthew. State and Society in the Early Middle Ages: The Middle Rhine Valley, 400–1000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry. The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. 3rd ed. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991.

- McKitterick, Rosamond. Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- McKitterick, Rosamond. The Carolingians and the Written Word. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Nelson, Janet L. King and Emperor: A New Life of Charlemagne. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019.

- Noble, Thomas F. X. The Republic of St. Peter: The Birth of the Papal State, 680–825. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984.

- Scholz, Bernhard Walter, with Barbara Rogers, trans. The Royal Frankish Annals. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1970.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.21.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.