By the time John Marshall left the bench in 1835, the nation he had helped to shape bore little resemblance to the confederation he had inherited.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

When the delegates gathered in Philadelphia in 1787, they were not merely amending the Articles of Confederation; they were writing its obituary. The new Constitution was conceived amid the failures of a decentralized system that could neither tax nor enforce its own laws, a framework that had bound thirteen sovereign republics together by little more than good will and paper promises. The Founders’ uneasy solution was federalism: a delicate balance between national authority and state autonomy. That balance would not endure long. In 1819, with McCulloch v. Maryland, Chief Justice John Marshall’s Supreme Court redrew the constitutional landscape, effectively shifting the locus of sovereignty from the states to the federal government. The ruling did not merely interpret the Constitution; it transformed the nature of the Union itself.1

The case arose from a seemingly provincial dispute—the State of Maryland’s attempt to tax the Baltimore branch of the Second Bank of the United States. Yet beneath that act of taxation lay an older struggle: the lingering contest between the compact theory of the Union, cherished by Jeffersonian Republicans, and the nationalist vision championed by Alexander Hamilton and the Federalists. The question was not just whether Congress could create a bank, but whether the federal government could act in ways not expressly enumerated in the Constitution. The answer Marshall gave, yes, if the end was legitimate and the means “appropriate,” breathed life into the doctrine of implied powers and, in doing so, recast the Constitution as a living instrument of national development.2

McCulloch was thus the hinge between the weak confederation of the eighteenth century and the consolidated republic of the nineteenth. By declaring that “the power to tax involves the power to destroy,” Marshall denied to the states any authority that could undermine federal institutions.3 The Supremacy Clause of Article VI, once a theoretical safeguard, became a practical doctrine: federal law was supreme, and the states were subordinate. The decision charted the course for the modern administrative state, laying the foundation for the federal government’s later authority to regulate commerce, mobilize state militias, and even federalize National Guard units without gubernatorial consent. In short, McCulloch v. Maryland marked the constitutional moment when the United States ceased to be merely united in name and became, in law and logic, one nation.

The Case and the Question: Can a State Tax the Union?

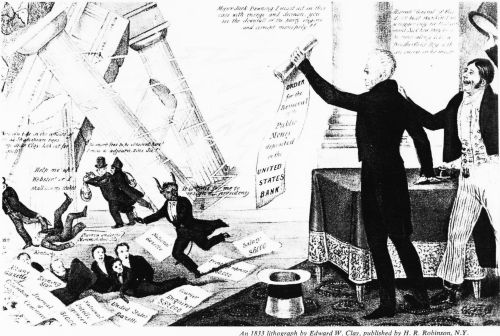

The early nineteenth century was an age of both consolidation and suspicion. The War of 1812 had underscored the need for a stable financial infrastructure, yet the rechartering of a national bank reopened old ideological wounds. To Jeffersonians, the Second Bank of the United States was not a neutral financial instrument but a political weapon, a Hamiltonian creation that seemed to mock the principle of limited government.4 When Maryland enacted a tax on all banks not chartered by the state in 1818, it aimed less at revenue than at resistance. The target was clear: the Baltimore branch of the national bank.

James McCulloch, the branch’s cashier, refused to pay the tax. Maryland sued and prevailed in its own courts, arguing that the Constitution contained no explicit authorization for Congress to create a bank, and that the state retained sovereign power to tax any entity within its borders.5 The federal government, through the Bank, appealed to the Supreme Court. Beneath the procedural veneer lay a constitutional question that went to the heart of American governance: Did the federal government possess powers not explicitly enumerated in the Constitution, and could a state exert authority over federal operations?

The tension was not new. In The Federalist No. 44, James Madison had warned that the federal government must possess sufficient implied powers to fulfill its duties.6 Yet opponents like Thomas Jefferson had argued in his 1791 opinion against the first bank that “to take a single step beyond the boundaries thus specifically drawn around the powers of Congress is to take possession of a boundless field of power.”7 The same line of division, between those who saw the Constitution as a grant of broad implied authority and those who viewed it as a narrow compact among states, had persisted into the early republic.

By the time McCulloch reached the Supreme Court in 1819, the nation had matured politically but remained divided constitutionally. The Court faced not a mere dispute over taxation but the unresolved question of what kind of union the United States had become. Maryland’s attorney, Luther Martin, invoked the compact theory, contending that the states were coequal sovereigns that had merely delegated certain powers upward to the general government.8 Daniel Webster, arguing for McCulloch and the Bank, countered that the people, not the states, were the true source of national authority, a position echoing Marshall’s own nationalist philosophy.9 The case thus pitted two visions of America against each other: one a league of states, the other a sovereign nation.

When the Court delivered its unanimous decision, it was not simply resolving a tax dispute but articulating the constitutional logic of nationhood. In ruling for McCulloch, Chief Justice Marshall affirmed the legitimacy of federal institutions operating free from state interference and positioned the federal government as supreme in its constitutional sphere. The question of whether Maryland could tax the Union was answered decisively: it could not, because to permit it would be to undo the Union itself. The conflict that began in a Baltimore courtroom ended as a redefinition of sovereignty in America.

Marshall’s Constitutional Reasoning: The Doctrine of Implied Powers

Chief Justice John Marshall’s opinion in McCulloch v. Maryland transformed constitutional interpretation by grounding federal power not in textual enumeration but in structural necessity. The Constitution, he argued, was “intended to endure for ages to come, and consequently, to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs.”10 That statement alone marked a philosophical break from the confederal mindset of the eighteenth century. It declared that the Constitution was not a static compact among states but a living framework capable of growth.

At the center of Marshall’s reasoning was the Necessary and Proper Clause (Article I, Section 8, Clause 18) which authorizes Congress “to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution” its enumerated powers. The word “necessary” had been the battleground of constitutional interpretation since the founding. Jefferson had read it narrowly: what is “necessary” must be “indispensably requisite.” Hamilton, defending the first Bank in 1791, had argued that the term meant whatever was useful or conducive to a legitimate end.11 Marshall sided with Hamilton’s view, expanding it even further. He wrote that “necessary” does not mean “absolutely necessary,” but rather “appropriate, plainly adapted to that end, and not prohibited.”12 In that linguistic maneuver, he embedded flexibility into the constitutional design.

The power to create a national bank, Marshall reasoned, was not explicitly granted, but it was a legitimate means of executing several enumerated powers: taxation, borrowing, regulating commerce, and providing for the general welfare. If the end is constitutional, he concluded, “all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are constitutional.”13 The Court thus validated the doctrine of implied powers, a principle that would sustain the expansion of federal authority from the early republic through the New Deal and beyond.

Marshall’s next step was to shield federal operations from state interference. His assertion that “the power to tax involves the power to destroy” captured the essence of federal supremacy: if a state could tax a federal instrument, it could, in effect, annihilate it.14 The Supremacy Clause of Article VI, long dormant in practical application, now had judicial force. Marshall wrote, “the government of the Union, though limited in its powers, is supreme within its sphere of action.”15 By this reasoning, Maryland’s tax was unconstitutional because it inverted the proper hierarchy of governance, subjecting the creator (the Union) to the created (the states).

Marshall’s jurisprudence in McCulloch exemplified his larger constitutional philosophy: that the United States was founded not as a compact among states but as a government deriving its authority directly from the people. This vision resonated with his earlier decisions, such as Marbury v. Madison (1803), where he had articulated judicial review, and it anticipated Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), where he would extend federal authority over commerce.16 The opinion in McCulloch thus completed a trilogy of constitutional construction, defining the judiciary as the interpreter of constitutional meaning and the federal government as the final arbiter of its own survival.

By redefining “necessary” as “appropriate and legitimate,” Marshall effectively constitutionalized elasticity. He turned the Constitution into a living instrument without ever abandoning its written authority. In doing so, he established a framework in which national growth could proceed under the guise of constitutional fidelity, a paradox that would animate American political debate for the next two centuries.

The Aftermath: Federal Supremacy and the Erosion of State Autonomy

The reverberations of McCulloch v. Maryland extended far beyond the courtroom. In declaring federal supremacy, the Court had not merely resolved a dispute over banking; it had redefined the nature of American federalism. The decision inaugurated a new constitutional order, one that favored national unity over local autonomy and transformed the relationship between the central government and the states from partnership to hierarchy.17

Reaction was swift and divided. Jefferson, then in retirement, condemned the ruling as “a single step toward despotism,” lamenting that “the federal branch has swallowed up all others.”18 His critique reflected an enduring republican anxiety: that centralized power, even when constitutionally justified, would erode the liberties of the people by diminishing the independence of their states. State legislatures across the South echoed these fears, passing resolutions denouncing the Court’s encroachment on state sovereignty. Yet to nationalists, McCulloch represented the necessary maturation of the Union. Daniel Webster hailed it as “the true exposition of the Constitution,” a bulwark against the centrifugal tendencies that had nearly undone the Confederation.19

In legal doctrine, McCulloch laid the foundation for a series of decisions that would steadily expand federal authority throughout the nineteenth century. In Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), Marshall applied the same logic of constitutional elasticity to the Commerce Clause, striking down New York’s steamboat monopoly on the grounds that navigation was a form of interstate commerce subject to federal regulation.20 Later cases such as Cooley v. Board of Wardens (1852) continued to grapple with the tension between local regulation and national uniformity, but the presumption of federal supremacy remained intact.21

The conceptual shift wrought by McCulloch also influenced political practice. Presidents and Congress alike began invoking the language of “implied powers” to justify measures far beyond the founders’ imagination—internal improvements, tariffs, and ultimately, wartime executive actions. The doctrine that had once defended a national bank now served as the legal scaffolding for the modern administrative state.22 The nation’s identity, once plural, the United States are,” increasingly became singular: “the United States is.”

Yet this consolidation was not universally accepted. Southern constitutionalists, from John C. Calhoun to the secessionists of 1861, would cite McCulloch as evidence of the federal government’s dangerous ambition. Calhoun argued that the decision “struck a deadly blow at the sovereignty of the States” and made nullification the last refuge of constitutional balance.23 His protests, however, only confirmed the durability of the very system he opposed. The idea that federal law was supreme, and that the Supreme Court was its final interpreter, had become woven into the fabric of national governance.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the dual sovereignty imagined by the framers had become a legal fiction. The federal government, armed with Marshall’s logic, stood as the final arbiter of its own powers. Federal supremacy was no longer a contested principle but an operational reality, visible in commerce, taxation, and the slow but steady nationalization of public life. What began as a defense of the Bank of the United States became the constitutional foundation of the modern state.

From the Bank to the Barracks: Federal Power in Military Context

The logic Chief Justice Marshall forged in McCulloch v. Maryland did not remain confined to the world of finance. Once accepted that federal instruments were supreme within their constitutional sphere, that reasoning naturally extended to military and police powers. The same doctrine that insulated a national bank from state taxation later enabled the federal government to command state militias and, in moments of crisis, to override gubernatorial control.24

The constitutional basis for this reach lay in Article I, Section 8, which authorizes Congress to “provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.” Early presidents, however, were cautious in wielding that power. When domestic disturbances arose in the 1790s, most famously the Whiskey Rebellion, President Washington invoked both federal and state cooperation.25 But the precedent for unilateral federal deployment was set when Thomas Jefferson signed the Insurrection Act of 1807, empowering the president to use military force to enforce federal law whenever “the ordinary course of judicial proceedings” proved insufficient.26 It was an irony of history: the man who had once insisted on narrow construction now provided the legal mechanism for expansive federal coercion.

Marshall’s reasoning in McCulloch gave the Insurrection Act its constitutional armor. If Congress could create institutions “plainly adapted” to its legitimate ends, it could also authorize means of enforcement beyond the states’ control. The same supremacy that shielded the Bank from Maryland’s tax now shielded the Union’s authority from local defiance. Later presidents, from Eisenhower’s deployment of federal troops to Little Rock in 1957 to George H. W. Bush’s use of troops in Los Angeles in 1992, would rely on that statutory lineage.27

The post–Civil War era produced an apparent limit: the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, which prohibited the use of the Army for domestic law enforcement absent explicit congressional authorization.28 Yet even this restraint proved conditional. The Act itself exempted circumstances permitted by the Constitution or other statutes, precisely the opening provided by the Insurrection Act. Thus, the very check intended to confine federal power reinforced it in practice. The president, not the governor, would decide when civil disorder justified federal intervention. When modern National Guard units are “federalized,” the echo of McCulloch can still be heard: state authority yields to the superior law of the Union.

In this way, the case that began with a tax on a bank became a jurisprudence of command. Marshall’s phrase “appropriate and legitimate” proved elastic enough to justify both economic regulation and military mobilization. The constitutional imagination he unleashed allowed the federal government to act wherever the “ends of the Union” required, transforming the old compact of states into an integrated system of national sovereignty capable of enforcing its own will, by law, or by arms.

Conclusion: The Federal Leviathan and the Living Constitution

By the time John Marshall left the bench in 1835, the nation he had helped to shape bore little resemblance to the confederation he had inherited. The constitutional principles articulated in McCulloch v. Maryland had become the architecture of a robust national government, one capable of legislating, adjudicating, and enforcing across a continental republic. The ruling transformed the Constitution from a skeletal document of enumerated powers into a living organism whose vitality lay in its capacity to adapt.29

Marshall’s doctrine of implied powers did more than expand federal jurisdiction; it redefined the meaning of constitutional fidelity. To interpret the Constitution “with the letter and spirit” of its design, he argued, was to recognize its elasticity. That flexibility allowed the United States to govern a growing population, wage wars, manage commerce, and preserve union during crises the framers could never have foreseen. In this sense, McCulloch laid the intellectual foundation for later national experiments (the Reconstruction Amendments, the New Deal, the Civil Rights Movement) all of which rested upon the same presumption of federal supremacy he had established.30

Yet the triumph of nationalism carried a democratic paradox. As the federal government assumed new powers, the distance between authority and the citizen expanded. The very efficiency that secured national coherence also diluted local control. Political theorist Sanford Levinson has observed that Americans developed a “constitutional faith” that replaced civic vigilance with legal abstraction, the belief that structure alone could safeguard liberty.31 That faith, born of McCulloch’s logic, risked turning constitutional interpretation into a priesthood of jurists rather than a practice of citizens.

Nevertheless, the decision’s enduring strength lies in its realism. Marshall understood that no republic could long endure if every state could impede the national will. His vision, like the Constitution itself, was pragmatic rather than idealistic. In the crucible of 1819, when the young republic teetered between union and disunion, McCulloch v. Maryland gave it coherence. The Court did not create federal power, it recognized it as a necessity of survival.

Two centuries later, the echoes of McCulloch persist in every debate over the reach of government, from healthcare mandates to environmental regulation. Each controversy replays the same constitutional drama: whether the ends of the Union justify the means chosen by its agents. The decision’s legacy is therefore double-edged. It enshrined the principle that national power must be effective, but also that it must remain accountable to the Constitution’s spirit. In that tension, between energy and restraint, resides the living Constitution Marshall envisioned, and the fragile equilibrium that continues to define the American experiment.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969), 354–359.

- McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316, 421 (1819).

- Ibid., 431.

- Bray Hammond, Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957), 170–176.

- McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316, 317–320 (1819).

- James Madison, The Federalist No. 44, in The Federalist Papers, ed. Clinton Rossiter (New York: Signet Classics, 2003), 283–287.

- Thomas Jefferson, “Opinion on the Constitutionality of a National Bank,” February 15, 1791, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 19, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974), 275.

- McCulloch v. Maryland, arguments of counsel, 17 U.S. 353–368.

- Daniel Webster, The Writings and Speeches of Daniel Webster, vol. 6, ed. James W. McIntyre (Boston: Little, Brown, 1903), 23–24.

- McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316, 415 (1819).

- Alexander Hamilton, “Opinion on the Constitutionality of the Bank,” February 23, 1791, in The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 8, ed. Harold C. Syrett (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965), 97–134.

- McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 421.

- Ibid., 421–422.

- Ibid., 431.

- Ibid., 436.

- R. Kent Newmyer, John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001), 132–139.

- Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 79–82.

- Thomas Jefferson to Spencer Roane, September 6, 1819, in The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 10, ed. Paul Leicester Ford (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1899), 141.

- Daniel Webster, quoted in Charles F. Hobson, The Great Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Rule of Law (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1996), 167.

- Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 1 (1824).

- Cooley v. Board of Wardens, 53 U.S. (12 How.) 299 (1852).

- Herbert J. Storing, What the Anti-Federalists Were For (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), 91–95.

- John C. Calhoun, A Disquisition on Government (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1851), 27.

- Charles Doyle and Jennifer K. Elsea, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters: The Use of the Military to Execute Civilian Law (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2012), 1–6.

- Richard H. Kohn, Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783–1802 (New York: Free Press, 1975), 203–208.

- Insurrection Act of 1807, 2 Stat. 443 (1807).

- William C. Banks and Stephen Dycus, Soldiers on the Home Front: The Domestic Role of the American Military (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 44–48, 173–175.

- Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, 20 Stat. 152 (1878).

- Akhil Reed Amar, America’s Constitution: A Biography (New York: Random House, 2005), 299–303.

- Mark A. Graber, “Constitutional Politics: The Reconstruction Strategy for Protecting Rights,” Faculty Scholarship 1390 (2013): 30-98.

- Sanford Levinson, Constitutional Faith (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988), 41–44.

Bibliography

- Amar, Akhil Reed. America’s Constitution: A Biography. New York: Random House, 2005.

- Banks, William C., and Stephen Dycus. Soldiers on the Home Front: The Domestic Role of the American Military. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Calhoun, John C. A Disquisition on Government. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1851.

- Cooley v. Board of Wardens, 53 U.S. (12 How.) 299 (1852).

- Doyle, Charles, and Jennifer K. Elsea. The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters: The Use of the Military to Execute Civilian Law. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2012.

- Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 1 (1824).

- Graber, Mark A. “Constitutional Politics: The Reconstruction Strategy for Protecting Rights.” Faculty Scholarship 1390 (2013): 30-98.

- Hamilton, Alexander. “Opinion on the Constitutionality of the Bank,” February 23, 1791. In The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 8, edited by Harold C. Syrett, 97–134. New York: Columbia University Press, 1965.

- Hammond, Bray. Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Hobson, Charles F. The Great Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Rule of Law. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1996.

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Insurrection Act of 1807, 2 Stat. 443 (1807).

- Jefferson, Thomas. “Opinion on the Constitutionality of a National Bank,” February 15, 1791. In The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 19, edited by Julian P. Boyd, 275. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974.

- ———. Letter to Spencer Roane, September 6, 1819. In The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 10, edited by Paul Leicester Ford, 141. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1899.

- Kohn, Richard H. Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783–1802. New York: Free Press, 1975.

- Levinson, Sanford. Constitutional Faith. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Madison, James. The Federalist No. 44. In The Federalist Papers, edited by Clinton Rossiter, 283–287. New York: Signet Classics, 2003.

- McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316 (1819).

- Newmyer, R. Kent. John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001.

- Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, 20 Stat. 152 (1878).

- Storing, Herbert J. What the Anti-Federalists Were For. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

- Webster, Daniel. The Writings and Speeches of Daniel Webster. Vol. 6, edited by James W. McIntyre. Boston: Little, Brown, 1903.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.17.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.