For the medieval observer, the moon was a constant companion whose phases ordered the most intimate aspects of life. The lunar cycle was a bridge between the visible and the invisible.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Celestial Companion of Earthly Life

In the medieval European worldview, the moon was far more than a luminous ornament of the night sky. It was an active, dynamic agent in the ordering of the natural world, believed to shape the rhythms of agriculture, the balance of the human body, and the ebb and flow of emotional life. Its phases were thought to exert tangible effects on plants, animals, and people, drawing on a long inheritance of classical natural philosophy and medical theory. The moon was not a passive reflector of the sun’s light, but a ruler of moisture, a regulator of bodily humors, and a mirror of human changeability.1

To understand this worldview is to enter a cosmology in which the celestial and terrestrial realms were part of the same continuum, bound by a web of sympathies and correspondences. In such a framework, the moon’s waxing and waning were not simply visual phenomena; they were signs of subtle material forces coursing through every living thing.

The Moon in Medieval Cosmology: A Planet of the Sublunary Sphere

In the Ptolemaic system, which dominated medieval European astronomy, the moon occupied a unique place as the closest of the seven “planets” to Earth, residing in the lowest of the celestial spheres.2 This proximity meant it was the most intimately involved with the mutable world below the sphere of the moon, known as the sublunary realm, where change, decay, and generation were possible.

Aristotle’s Meteorologica and De Caelo framed the moon as the chief intermediary between the incorruptible heavens and the mutable Earth.3 Its cycles, visible to all, were treated as a kind of cosmic clock that measured time and signaled transitions in natural processes. Medieval scholastic thinkers inherited this model, incorporating it into Christian natural philosophy while integrating biblical associations, such as the moon’s role in Genesis as a “lesser light” set to govern the night.

The Moon and the Humors

Moisture and the Waxing Moon

Medieval medicine was grounded in the Galenic theory of the four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) each associated with qualities of heat, cold, moisture, and dryness. The moon’s influence was understood primarily in terms of moisture. Drawing on both Aristotle and Hippocrates, physicians believed that the waxing moon increased the moisture in the human body, particularly augmenting phlegm.4 This was linked to the moon’s supposed power over tides, a phenomenon widely observed and taken as proof of its dominion over all fluids.

During the waxing phase, bodies were thought to be more “full” and more responsive to nourishment, making it an auspicious time for certain treatments. Conversely, the waning moon was believed to dry the humors, making the body less susceptible to swelling but also less resilient to blood loss.

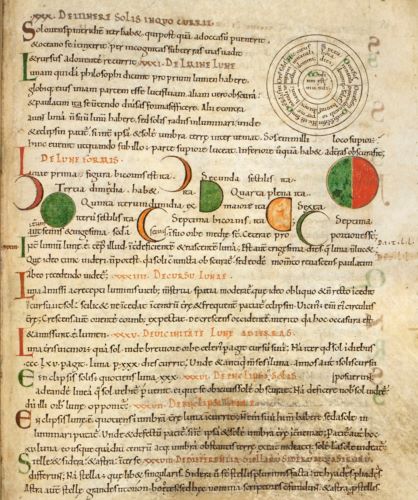

Timing Medical Procedures

The lunar calendar played a central role in medieval medical practice. Physicians consulted lunar tables when scheduling bloodletting, purges, and even surgical interventions. For example, operations were often avoided during the full moon because of the belief that increased bodily moisture heightened bleeding risk.5 The waning moon was preferred for procedures requiring reduction, whether of excess blood, phlegm, or melancholic humor, since the lunar phase was thought to align with the body’s own drying tendency.

Such practices were codified in medical almanacs, which offered precise instructions on when to administer remedies or avoid particular interventions, merging astronomy, astrology, and medicine into a single operational art.

Agricultural Rhythms Under Lunar Light

Sowing, Harvesting, and the Moon’s Phases

Farmers, too, worked to the beat of the moon’s changing face. The waxing moon was seen as a time of growth, when the “moisture” of the Earth was at its height, nourishing the germination of seeds. Crops planted during this phase were believed to grow taller and stronger.6 Conversely, the waning moon, with its drying influence, was considered ideal for harvesting and for planting crops where sturdier, more compact growth was desired.

These beliefs were reinforced by centuries of agricultural observation and embedded in rural calendars. The monastic estates that kept detailed planting records often preserved these lunar guidelines, which blended practical experience with the authority of learned tradition.

Lunar Influence on Weather

The moon was also thought to affect weather patterns through its control over moisture in the air. A bright, haloed moon could be taken as a sign of impending rain, while its orientation in the sky was read as an omen for wind or frost. Such meteorological readings were not separate from the moon’s supposed bodily influence; both were expressions of the same cosmic principle that moisture moved in sympathy between heaven and Earth.

The Moon as a Mirror of the Mind: Emotional Changeability

In medieval literature, the moon often served as a metaphor for human inconstancy. Its ceaseless change of form across the month was likened to the shifting temperaments of lovers, rulers, and even entire communities.7 Poets and moralists could point to the moon as a celestial emblem of mutability, drawing moral lessons from its phases.

In medical theory, too, the moon was implicated in emotional states. An excess of moisture during the waxing phase was believed to incline individuals toward melancholy or lethargy, while dryness in the waning phase might bring irritability or restlessness. The word “lunatic” itself reflects the enduring association between the moon and mental instability. Although modern psychiatry has rejected the lunar causation of mental illness, in the medieval mind the link was entirely plausible, grounded in the same humoral logic that connected the moon to tides and bodily fluids.

Conclusion: A World in Lunar Rhythm

For the medieval observer, the moon was a constant companion whose phases ordered the most intimate aspects of life. It governed the flow of blood in the physician’s clinic, the timing of seed and harvest in the farmer’s field, and the ebb and flow of temperament in the human heart. The lunar cycle was a bridge between the visible and the invisible, the measurable and the mysterious.

What emerges from this picture is not mere superstition, but a coherent worldview in which celestial bodies were integrated into an intricate network of cause and effect. The moon’s influence on moisture, whether in the sea, the soil, or the self, was a cornerstone of medieval natural philosophy. That this belief persisted for centuries speaks to the human impulse to find patterns in the sky and to align the rhythms of life with those of the heavens.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Nancy G. Siraisi, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 47–49.

- Edward Grant, Planets, Stars, and Orbs: The Medieval Cosmos, 1200–1687 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 47–50.

- Aristotle, Meteorologica, trans. H.D.P. Lee (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1952), 339b–340a.

- Hippocrates, Airs, Waters, Places, in Hippocratic Writings, ed. G.E.R. Lloyd (London: Penguin Classics, 1978), 148–150.

- Monica H. Green, “The Sources of Medieval Science,” in The Cambridge History of Science, vol. 2, Medieval Science, ed. David C. Lindberg and Michael H. Shank (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 310–313.

- Richard C. Hoffmann, An Environmental History of Medieval Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 102–104.

- Caroline Walker Bynum, Metamorphosis and Identity (New York: Zone Books, 2001), 55–57.

Bibliography

- Aristotle. Meteorologica. Translated by H.D.P. Lee. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1952.

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. Metamorphosis and Identity. New York: Zone Books, 2001.

- Grant, Edward. Planets, Stars, and Orbs: The Medieval Cosmos, 1200–1687. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Green, Monica H. “The Sources of Medieval Science.” In The Cambridge History of Science, vol. 2, Medieval Science, edited by David C. Lindberg and Michael H. Shank, 300–328. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Hippocrates. Airs, Waters, Places. In Hippocratic Writings, edited by G.E.R. Lloyd. London: Penguin Classics, 1978.

- Hoffmann, Richard C. An Environmental History of Medieval Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Siraisi, Nancy G. Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.13.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.