What makes a monster? A monster is seen to be any creature that deviates from the norm…We feel pity and compassion, but we are also greatly unsettled.

John & Caitlin Matthews, The Element Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures, 2008

Introduction

Monsters are timeless. From ancient mythology to modern day entertainment, monsters have remained popular and captivating. As such, tales dating back to antiquity are ripe with monstrous and fantastical beings. The ancients often fused the fantastic with the natural, cultivated this ideology, and passed it down through the ages, persisting in studies of the natural world for many centuries. Eventually these stories evolved into the creation of entirely fictional literature that draws from the ancients and mirrors the evil of men through monstrous beings and the eternal struggle between good and evil.

This article features mythological monsters of the Classical, Germanic and Jewish peoples; supposedly natural creatures such as dragons, merfolk, animal/human hybrids and others that appear in natural history works of the medieval and early modern period; plus later Gothic literary titans such as Frankenstein, Dracula and the nefarious Mr. Hyde; and concludes with modern-day examples from the hit Harry Potter franchise.

Monsters of Ancient Myth and Legend

Overview

Monsters appear in ancient mythology dating back thousands of years. From the sphinx of ancient Egypt (a hybrid creature with the body of a lion and human head), to Xiangliu, the nine-headed snake of Chinese mythology, monsters are found in myths, legends and folklore of cultures all around the world. Some of the most popular examples from Western culture originated in the Classical myths of Ancient Greece and Rome, as well as the Ancient Germanic myths.

Medusa

One of the most famous tales of Greek mythology depicts the female monster, Medusa. She was said to be one of the three Gorgon sisters of the sea god, Phorcys. She was thought to be among the most beautiful of women until she defiled the temple of Athene and was cursed by the gods. Her punishment was to be turned into a monster so that none could look upon her without being turned into stone. She was described as having wings and tangled snakes instead of hair. She was eventually slain by the mythical hero, Perseus, and even after death, her head held its magical power and was used to turn the Titan, Atlas, to stone.

The Minotaur

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur was a man with the head of a bull, a monstrous human-bull hybrid, who dwelt in the midst of a labyrinth within the castle of King Minos on the island of Crete. According to the myth, the Athenians were responsible for the death of Minos’s son, Androgeus, and thus, either to avert a plague caused by the crime, or by other accounts, due to the loss of a war brought on by the death, Athens was forced to send periodic tributes of seven male youths and seven female maidens to be sacrificed to the Minotaur, who fed on human flesh. This continued until the Athenian hero, Theseus, volunteered to become one of the tributes, fought and killed the Minotaur, and used a ball of red twine given to him by Minos’s love-struck daughter, Ariadne, to lead his fellow Athenians out of the monster’s great labyrinth.

Beowulf

In the epic poem, Beowulf, which is one of the most important Old English literary works, the protagonist, Beowulf, the nephew of the King of the Geats, comes to the aid of Hrothgar, king of the Danes and fights against several monsters. Two of the characters are Grendel and his mother, which are described as troll-like monsters. Trolls originate from Norse mythology and Scandinavian literature and were said to be unfriendly, easily tricked and of a larger stature than humans. They could be found in mountains, caves and rocks and had a preference for human flesh when available. They were often included in literature to positively contrast the hero of the story. After the defeat of Grendel and his mother, Beowulf becomes King of the Geats and eventually dies while killing a cursed dragon, the third and final monster that he faces in the tale.

Sirens

Sirens were said to be some of the most dangerous of sea monsters. They lured sailors to their deaths by enchanting them through music and singing. They were described as a combination of woman and bird, with the head of a woman but having bird feathers and scaly feet. The most famous literary appearance of the sirens was in Homer’s Odyssey as they attempted to draw Odysseus and his crew to their deaths on the way home from the Trojan War. The only way that they avoided death was to stop their ears with wax to avoid hearing the sirens’ beckoning songs. According to legend, Odysseus and his crew were fortunate as there were many souls lost to the sirens.

The description in this natural history work resembles much of the story told by Homer:

Siren, the mermaid is a deadly beast that bringeth a man gladly to death. From the naval up she is like a woman with a dreadful face, long slimy hair, a great body, and is like the eagle in the nether part, having feet and talons to tear asunder such as she geteth; her tail is scaled like a fish, and she singeth a manner of sweet song and therewith deceiveth many a good mariner, for when they hear it they fall on sleep commonly and then she cometh and draweth them out of the ship and teareth them asunder… But the wise mariners stop their ears when they see her, for when she playeth on the water they be in fear and then they cast out an empty tone to let her play with it till they be past her. This is specified of them which have seen it. There be also in some places of Arabia serpents named Sirens that run faster than an horse and have wings to fly.

Transcribed from An early English version of Hortus sanitatis (1520’s; Reprinted 1954), Reynolds-Finley Historical Library.

Cyclopes

Originating from both Greek and Roman mythology, the Cyclopes were one-eyed monsters that descended from the giants. They first gained notoriety when they fought alongside Greek god, Zeus, against the Titans, and they were said to live on a remote island. They fed on human flesh, and had a reputation of being easily duped by passing travelers. The chief of the Cyclops, Polyphemus, appears in the famous epic, the Odyssey, when the main protagonist, Odysseus visits the island of the Cyclops. The myth goes that Polyphemus trapped Odysseus and his men in a cave to feast on them, but Odysseus lured him into a deep sleep and blinded him in order to escape.

Medieval Monsters

Overview

Medieval bestiaries were pictorial compendiums of animal-kind which often included the real alongside the mythical with tales and parodies of the beasts caged in a moralistic tone or portraying their symbolic nature. Different animals possess different strengths and weaknesses, and so one theory on the prevalence of mythical hybridization is that those imagining them are trying to combine those powers for symbolic moral purposes. The same type of creatures populate the margins of many medieval manuscripts, sometimes with the same moralistic tone, but other times simply reflecting the vivid imaginations of illuminators.

Pegasus

“Pegasus is a mighty great beast and it is in the land of Ethiopia and is formed like an horse with wings greater than an eagle, and it hath great horns in his head, and it is like a monster for all other beasts be of it afraid. It hath a great body and it runeth very swiftly through help of his wings, and it eateth much and persecuteth other beasts very sore, but it persecuteth man most of all.”

An early English version of Hortus sanitatis (1520’s; Reprinted 1954).

Giraffe and Onocentaur

“Oraffius (Giraffe) is a beast having many colors and the fore part of his body is very high in such a manner that he may reach with his head 20 cubits, but the hinder part of him is very low, and it is footed and tailed like an hart.

Onocenthaurus (Onocentaur) is a beast and monster having a head like an ass, and all the other parts of the body is like a man. And when it beginneth to cry then it seemeth that it will speak but it cannot, and he throweth stones… with great strength at them that follow him for to take him. Adellin sayeth that this beast was not made at the beginning when all other beasts were created of god but that they come of a marvelous commission and strange generation.”

An early English version of Hortus sanitatis (1520’s; Reprinted 1954).

Monsters of Medieval Natural History

Using information derived from earlier medieval encyclopedias, Hortus Sanitatis, or “The Garden of Health” (1497), is considered one of the most important illustrated works documenting natural history from the Middle Ages. It contains over 1000 hand-colored woodcuts of all the animals, plants, gems, and stones believed to exist at the time. In the Middle Ages, when travel was difficult and so much of the world unknown, legends of fantastical monsters and beasts seemed as likely and provable as those of real animals living in far-off lands.

Also, the writings of ancient Greek and Roman scholars persisted as authoritative sources of knowledge of the natural world. Since those ancient writers, such as Pliny the Elder (AD 23/24 – 79), Aelian (c. 175 – c. 235 AD) and Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BC), often infused mythology into their works, these ideas were passed down as well. Stories of the existence of these creatures remained in natural history works through the early modern period, taking many years to sort truth from fantasy.

In Hortus Sanitatis, mythical monsters appear confidently alongside known species in far-off lands, such as the giraffe who shares a woodcut with the unreal animal called Onocentaur. After all, there was just as much evidence of their existence from the perspective of the book’s publisher. Also displayed is the Cephos (right), who has the body of a man and the head and mouth of a blood-hound, and who appears to be in conversation with a lion. According to the text, this monster has been seen in the plays at the theater of Pompeyus in Rome.

The animals within Hortus Sanitatis reflect the challenges faced by those trying to depict nature during this period. Amongst the sea monsters is a pair of what looks to be merfolk with inadequate facial features on the head, but eyes and mouths displaced on the torso. This is actually an attempt to depict dolphins (box to the right) by one who has clearly not had the opportunity to see them first-hand, living in a time long before photography. Therefore, some of the strange and hybrid animals within this book may reflect an attempt to describe actual animals by composing body parts of known species. Another example is the marmoset, a real ape that is depicted with a human face (left, above).

Griffin

“The grype (Griffin) is both bird and beast and it hath wings and feathers and four feet and the whole body like the lion, and the head and forefeet and wings be like the eagle, and they be enemies both to horse and man, for when they may get them they tear them asunder. In Scythia of Asia be right plentiful lands where as nobody cometh but these grypes, and that land is full of gold and silver and precious stones, and they be bred in the mountains of Hybori [Hyperborea], and they of Arismaspi fighteth against them for the precious stones. Albert sayeth he hath claws as much as the hornes of an ox whereof they make dishes for to drink of and they be very rich and costly.”

An early English version of Hortus sanitatis (1520’s; Reprinted 1954).

Dolphins

“Delphin (Dolphin) is a monster of the sea and it hath no voice but it singeth like a man and toward a tempest it playeth upon the water. Some say when they be taken that they weep. The dolphin hath none ears for to hear, nor no nose for to smell, yet it smelleth very well and sharp… They hear gladly playing on instruments as lutes, harps, tambours, and pipes. They love their young very well and they feed them long with the milk of their pups and they have many young and among them all 2 old ones that if fortuned one of the young to die that these old ones will bury them deep in the ground of the sea because other fishes should not eat this dead dolphin so well they love their young.”

An early English version of Hortus sanitatis (1520’s; Reprinted 1954).

Monsters of the Early Modern Period

Overview

During the 1500s and 1600s, scholarly inquiry into the anomalies of nature was beginning to transform into the scientific study of teratology, but myths still abound of the fantastical monsters that could be found in distant lands, and strange, fanciful cases of half-human, half-beast hybrids continued to populate this literature. Evidence from the ancient scholars still held sway over empirical verification, but the Scientific Revolution was beginning to transition this mindset. Thus scholars worked to catalogue the reported cases of the marvelous throughout history in order to determine their veracity.

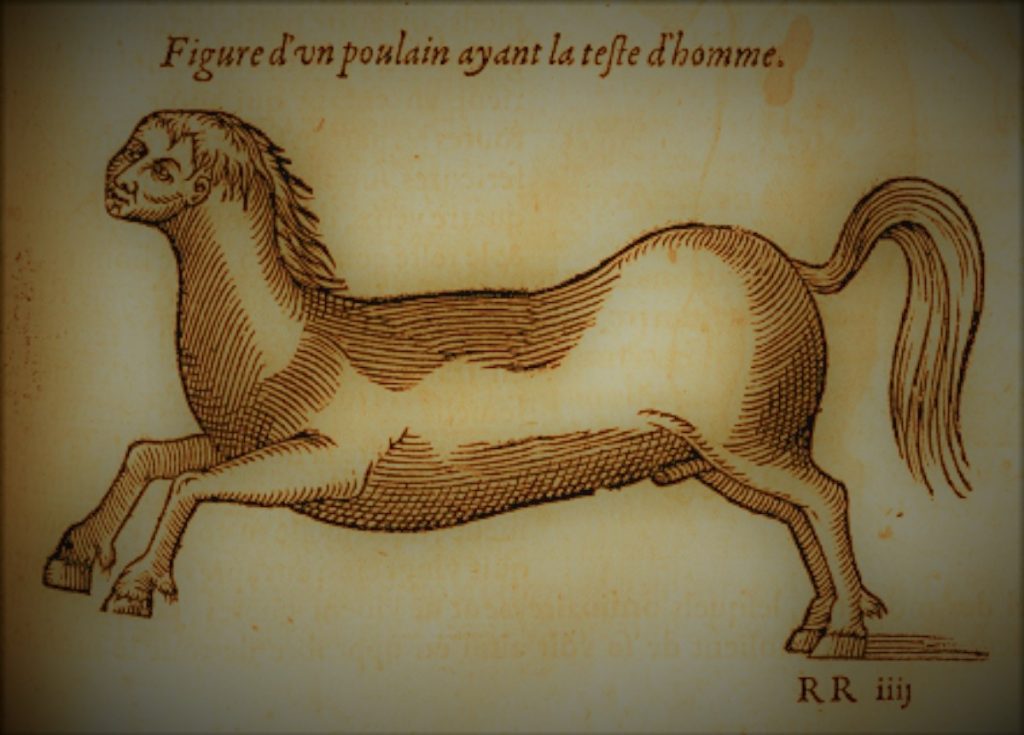

Pare’s Monsters

French surgeon Ambroise Pare (1510-1590), provided one of the first attempts to describe and explain birth defects and anomalies in his Des Monstres et Prodiges, or On Monsters and Marvels (1573). Pare tried to identify the causes of anomalies as well, noting both natural and supernatural influences, such as sorcery, creation by imagination (see the boy with a frog face above), and the notion that the birth of monsters portend unfortunate events. For example, he records that in the year 1254, a war took place between the Florentines and Pisans in Italy after a colt was born in Verona with a man’s face. The monster was seen as an omen.

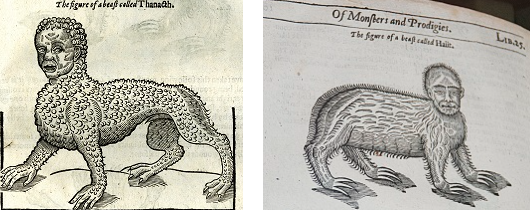

Monsters from Distant Lands

During the 16th century, few had the opportunity to travel to the Americas or the East. One who did was the French priest, explorer and cosmographer, Andre Thevet (1516-1590), a contemporary of Ambroise Pare, who reports many of Thevet’s animal sightings in his work. The Thanacth (left), was seen when Thevet was on the Red Sea, and he explained that the

“…bigness and shape of his limbs was not unlike a Tiger, yet had the face of a man, but a very flat nose: besides, his fore feet were like a mans hands, but the hinde like the feet of a Tiger, he had no tail, he was of a dun colour.” Pictured right is the “Haiit,” which “is bred in America” and is “of the bigness of a Monkey, with a great belly, almost touching the ground, and the head and face of a child.”

From The workes of that famous chirurgion Ambrose Parey (1634), in the Reynolds-Finley Historical Library.

Monster Tortoise

“I have taken this following monster out of Leo’s African history; it is very deformed, being round after the manner of a Tortoise, two yellow lines crossing each other at right angles, divide his backe, at every end of which he hath one eye, and also one eare, so that such a creature may see on every side with his foure eyes, as also heare by his so many eares: yet hath hee but one mouth, and one belly to containe his meat; but his round body is encompassed with many feet, by whose helpe he can go any way he please without turning of his body, his taile is something long and very hairy at the end. The inhabitants affirme that his blood is more effectual in healing of wounds than any balsome.”

From The workes of that famous chirurgion Ambrose Parey (1634), in the Reynolds-Finley Historical Library.

Pare’s Sea Monsters

The sea-monk we saw in Hortus Sanitatis, but Pare tells us also of the sea-bishop, which is described as a monster “in the manner of a Bishop, covered with scales, having his miter and pontifical ornaments, which was seen in Poland, in 1531…” (Pare, On Monsters and Marvels, 1982 translation by Janis L. Pallister).

Shown here are various sea monsters, within the 1634 English translation of Pare’s collected works. Click to enlarge and see more.

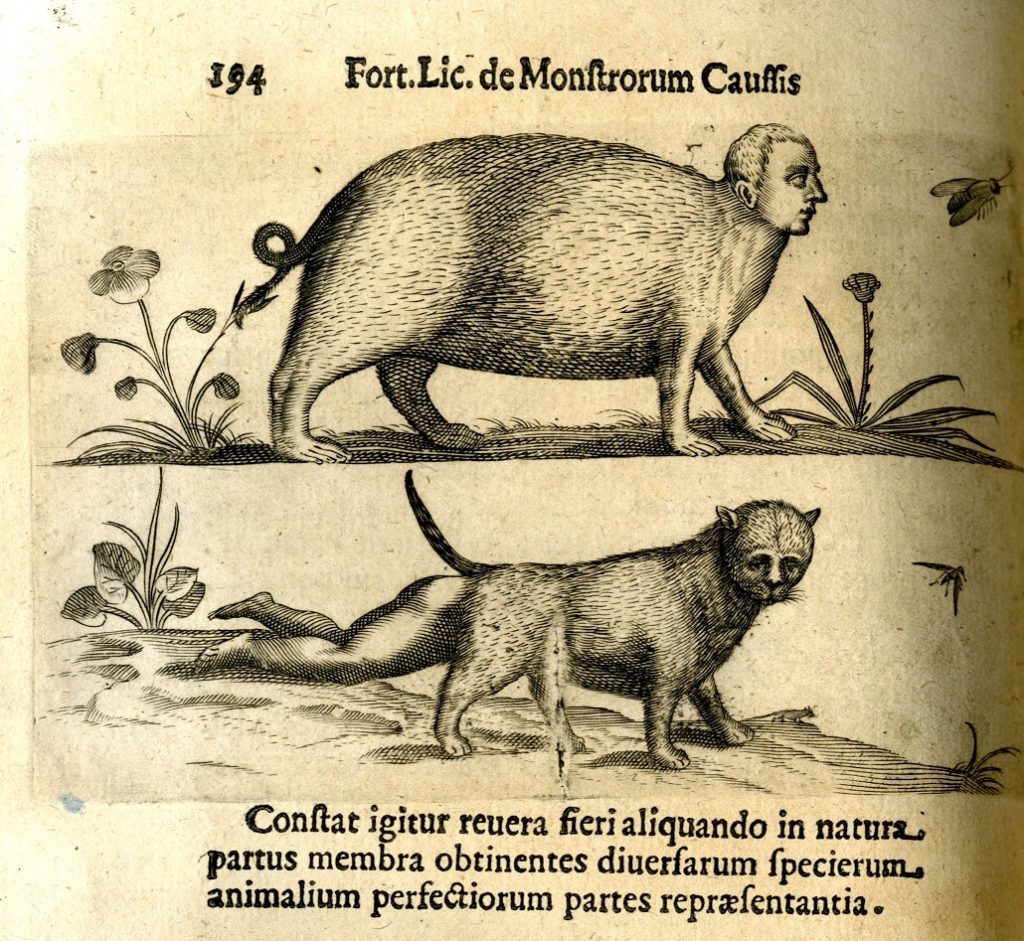

Liceti’s Monsters

In the 17th century, De Monstrorum Caussis, Natura, et Differentiis Libri Duo (1634), by Italian physician and philosopher, Fortunio Liceti (1577-1657), was the most influential work on the subject, and many of the same mythical monsters and hybrids from Pare are retained in Liceti’s reports. However, Liceti tried to provide more natural explanations of these beings, though the accounts he recorded from historical sources do not reject the supernatural. But his work signaled a shift to a more scientific approach as he attempted to catalogue all reported cases, classify and explain their causes, and unlike many before him, Liceti did not view monsters in a negative light. He writes, “It is said that I see the convergence of both Nature and art, because one or the other not being able to make what they want, they at least make what they can” (qtd. in the Public Domain Review).

Liceti’s Hybrids

“In the time of Albertus Magnus (ca. 1200 – November 15, 1280), on a particular farm [most likely near Cologne, Germany where Albertus Magnus lived], a cow gave birth to a half-human calf; the peasants being made to rally, seized the herdsman as if he was the accomplice in a great crime, and next they were going to burn the cow, but fortunately Albertus Magnus arrived, who they trusted on account of his versatile experience in the astronomical arts, that it was not some crime against humanity, but the influence of a certain position of the stars that existed for the birth of this elevated monster.

Plutarch (A.D. 46 – ca. 120) speaks of a pastoral young man, who he himself revealed as the offspring of a mare. On top all the way up to the neck and hands were of human form; the remaining parts having that of a horse; and crying in the manner of newly born human babies.”

From Liceti’s De Monstrorum… (1637), held in the Reynolds-Finley Historical Library.

Elephant-Boy

Liceti defends the existence of a young boy born with an elephant head in the manner shown here by listing all the various authors citing these cases from ancient times to his own: including Polydoros, Virgil (70-19 BC), Livy (59 BC– 17 AD), Fabio, Valerio, Maximo and Rueff (1500-1558 AD). This method of proof was common throughout the 17th century as verification from past authorities still carried significant weight.

Non-Human Monsters

“In 1577… in the community of Blandy near Melun, a three-headed lamb was born; the middle head was thicker than the rest; when one bleats the remaining heads bleat together. This monster was affirmed by John Bellanger, having seen it himself.

In my home, in Padua, in the year 1624, a handmaiden deplumed a fat hen of mine in order to boil it, and she discovered in it feet with five digits on both sides, each with its own distinct talons.”

From Liceti’s De Monstrorum… (1637), held in the Reynolds-Finley Historical Library.

Liceti Catalogues Monster Cases

Liceti’s description of the half-pig, half-human animal pictured below illustrates his dedication to cataloguing all recorded incidents of monster cases. He records the years on the side next to the pertaining incident, noting:

“1011: A female swine gives birth to a fetus brought forth with a human face.

1018: The same sort of monster having come forth after a few years.

1055: During the reign of Henry [Henry I of France who reigned from 1031-1060], a pregnant swine gave birth to a pig with a human head.

1109: In the parish of Lige a suckling pig which had the face of a human sprung forth from a mother pig.

1110-1118: As related by Pare and Lycosthenes, in a certain community of the Eburones, a pig brought forth of the litter one with the face, feet, and hands of humans; but the rest of the body recalling a swine.

1126: In Gaul, a similar monster arose.”

From Liceti’s De Monstrorum… (1637), held in the Reynolds-Finley Historical Library.

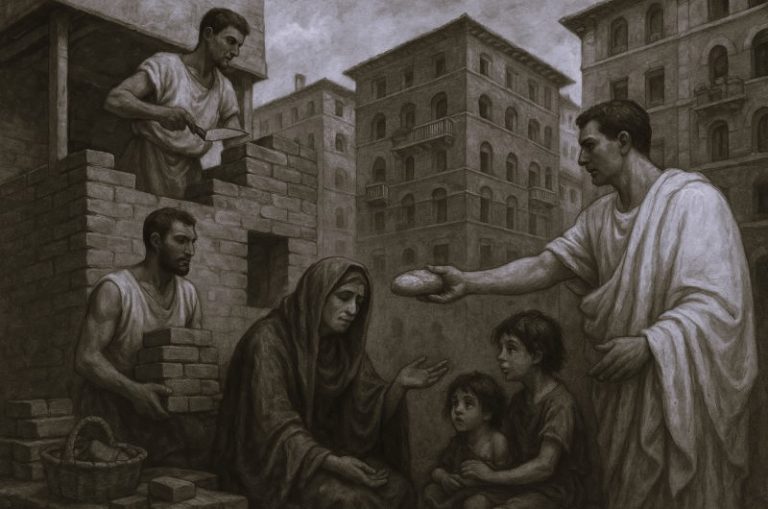

The Birth of Man-Made Monsters

At the same time as early modern physicians and naturalists were cataloguing, classifying and trying to explain the mysterious marvels of the natural world, another type of monster began to rise: those created entirely by man through science. Man-made monsters had their ideological origins in the Golem of Jewish folklore dating back to early Judaism. The Golem is an anthropomorphic being created out of inanimate matter, usually clay or mud. In the most famous tale involving Judah Loew ben Bezalel, a 16th century Rabbi of Prague, the clay Golem is brought to life through Hebrew ritual and incantation and defends the Prague Jews from anti-Semitic attacks.

Another man-made monster that arose during the 16th century is the alchemical homunculus, an ideological creation of the Swiss physician and alchemist, Paracelsus (1493/4 – 1541), who believed this “little man” could be made from scratch without the normal method of human procreation.

“Paracelsus considered both sperm and egg to have the full potential of life already within them… Paracelsus proposes that the life of the sperm can be brought to fruition ‘without the female body and the natural womb’… He attributes this to the fecund alchemical process of putrefaction, acting in some sense via the occult forces of ‘magnetism’”

Phillip Ball, The Devil’s Doctor, 2006

The idea of the monster made by man through scientific means also inspired the famous story, Frankenstein.

Monsters of Gothic Fiction

Overview

During the 1700s, as the world became better known through exploration and scientific experimentation, mythical monsters disappeared from studies of nature and medicine. But they became increasingly popular in the Gothic fiction that arose in the late 1700s and persisted as an important genre through the 1800s. Monsters of this literature personified the fears of society: fear of what happens when science is allowed to go too far; fear of the encroachment of contagious disease; and fear of the demons within ourselves.

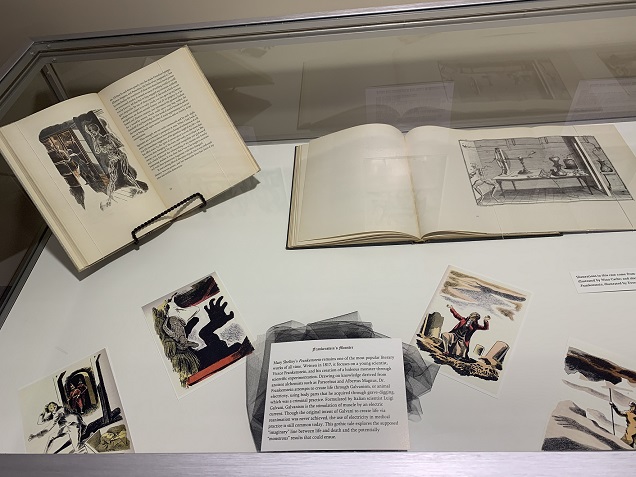

Frankenstein’s Monster

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein remains one of the most popular literary works of all time. Written in 1817, it focuses on a young scientist, Victor Frankenstein, and his creation of a hideous monster through scientific experimentation. Drawing on knowledge derived from ancient alchemists such as Paracelsus and Albertus Magnus, Dr. Frankenstein attempts to create life through Galvanism, or animal electricity, using body parts that he acquired through the criminal practice of grave-digging. Formulated by Italian scientist Luigi Galvani, Galvanism is the stimulation of muscle by an electric current. Though the original intent of Galvani to create life via reanimation was never achieved, the use of electricity in medical practice is still common today. This gothic tale explores the supposed “imaginary” line between life and death and the potentially “monstrous” results that could ensue.

Galvani’s Reanimation

This image depicts Luigi Galvani’s experiments on the use of electricity to reanimate frog limbs, the ideological basis for Frankenstein’s animation.

Dracula

Another Gothic tale, Dracula, written by Bram Stoker and published in 1897, focuses on one of the most popular literary monsters, the vampire Count Dracula. Based on folklore dating back centuries, vampires were known as undead creatures, or demons, that fed on the blood of the living to survive. While many folklore stories became recognized as more fictitious over the centuries, the belief in vampires gained momentum during the 18th century as several “vampire sightings” were reported and caused a mass hysteria throughout Eastern Europe, creating a rise in staking accounts and grave diggings to hunt the potential monsters.

The hysteria subsided with later generations, but the association between vampires of folklore and sufferers from the infectious disease, tuberculosis, lingered in the public consciousness. Also known as consumption, this contagious lung infection causes its victims to cough up blood and become pale, thin, and generally waste away toward death. As the disease had reached epidemic proportions during the Victorian era, Stoker’s Dracula met with a receptive audience.

The Evil Mr. Hyde

“All human beings, as we meet them, are commingled out of good and evil…”

From the 1945 edition of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, illustrated by Hans Alexander Mueller, in the Sterne Rare Book Collection.

Written by Robert Louis Stevenson, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (originally published in 1886), emphasizes the eternal struggle between good and evil and the ever-present existence of man’s inner demons. While Dr. Jekyll is seen as a morally good man with pure intentions, he secretly struggles with an inner evil personified in the emergence of literary monster, Mr. Hyde.

Though the behaviors and actions of the two greatly contrast, their fate is equally shared, revealing that man is capable of both good and evil, and oftentimes, both can dually exist. This Gothic tale remains one of the most influential literary works of its time and the antagonistic monster, Mr. Hyde, remains a popular villain.

Harry Potter’s Monsters

Overview

Published between 1997 and 2007, J. K. Rowling’s novel series about the young wizard, Harry Potter, and his struggles against the evil dark wizard, Lord Voldemort, was by 2018 the best-selling book series in history, and one of the most successful media franchises as well. The novels certainly include a menagerie of various monsters and mythical beasts, with literary roots in mythological traditions and medieval and early modern natural history. Many of Harry’s monstrous opponents and friends have already been discussed here – dragons, merfolk, centaurs, unicorns, trolls, and giants – but this adds a few more examples to our monsters list.

Fluffy, the Three-Headed Dog

In the first Harry Potter book, Harry, Ron and Hermione face a three-headed dog named Fluffy, who guards the trap door to a hidden area of the castle in which the Philosopher’s Stone is kept. The animal is ferocious but falls asleep to the sound of music. Greek mythology tells of a similar three-headed dog named Cerberus, who guards the entrance to the underworld and was once charmed to sleep by Orpheus playing his lyre.

Buckbeak, the Hippogriff

Shown on the cover of the third Harry Potter book is a hippogriff, which is a similar hybrid as the griffin, with the head, wings and front feet of an eagle, but with the hindlegs of a horse instead of a lion. In the Prisoner of Azkaban, Harry befriends the hippogriff named Buckbeak, who assists him with the book’s quest. The hippogriff also appears in mythology dating back to Classical times. The Roman poet Virgil (70 – 19 BC) provides an early account of the beast in his Eclogues.

Firenze, the Centaur

In the Harry Potter books the centaur Firenze teaches divination at Hogwarts, and the centaurs of the series are generally known for their abilities in divination, astronomy and healing. In the Harry Potter books as well as Classical mythology, centaurs possessed both wild, barbarous tendencies and human intelligence. It is said that the centaur of Greek mythology, Chiron, taught mankind the use of plants and medicinal herbs. The Greeks named the plant Centaury or “centaurion” in honor of Chiron, who possessed herbal knowledge and was the civilized antithesis to the usually wild centaurs. Chiron supposedly used this plant to cure a wound he received from Hercules’ poisoned arrow. Dioscorides ascribes many medicinal attributes to this plant, one of which was the healing of open wounds and sores.

The Basilisk

In the second Harry Potter book, a giant serpent called a basilisk who kills with his glance, lives in the Chamber of Secrets intent on killing off Muggle-born students. After its eyes are clawed out by the phoenix, Fawkes, Harry is able to kill it with the sword of Godric Gryffindor. The basilisk tale is not only reminiscent of the Medusa myth, but the monster also appears in early modern natural history, as seen here by its depiction in Hortus Sanitatis (1497). The great serpent is also described as having a “crooked bill like a cocke” and is born of a chicken egg.

Fawkes, the Phoenix

In the Harry Potter books, Professor Dumbledore has a pet phoenix named Fawkes who comes to Harry’s aid in the Chamber of Secrets. The bird’s tears have healing properties. But it concerns Harry when it spontaneously erupts into flames during a visit to Dumbledore’s office. These abilities are well-established in bird lore of the phoenix dating back centuries. As noted in the image above from An early English version of Hortus sanitatis (1521; Reprinted 1954),

“The phoenix is a bird in Arabia, of them is but one in the world, and he wereth 500 years old. And when he is thus old he gathereth the sticks of well smelling spices and buildeth a fire thereof, and then he splayeth his wings abroad towards the heat of the sun sitting on his wood and quickly he setteth on fire and so burneth, and of the ashes ariseth another phoenix.”

Bibliography

- Andrew, Laurence; Hudson, Noel; Bernard Quaritch (Firm). An early English version of Hortus sanitatis: a recent bibliographical discovery. London: B. Quaritch, 1954.

- Ball, Philip. The devil’s doctor: Paracelsus and the world of Renaissance magic and science. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

- Bulfinch, Thomas; Klapp, William H. The age of fable; or the Beauties of mythology. New York: The Heritage Press, 1942.

- Galvani, Luigi…De viribus electricitatis in motu musculari commentarius… Mutinae: Apud Societatem typographicam; MDCCXCII 1792.

- Harrison, Jane Ellison. Myths of the Odyssey in art and literature. London: Rivingtons, 1882.

- Hortus sanitatis. Strassburg: Johann Pruss, 1497.

- Le Clerc, Daniel. Histoire de la medecine… A La Haye: Chez Isaac van der Kloot; MDCCXXIX 1729.

- Leonard, William Ellery; Ward, Lynd. Beowulf. New York: The Heritage Press, c1939.

- Liceti, Fortunio. De monstrorum caussis, natura, et differentiis libri duo … Patavii: Apud Paulum Frambottum; MDCXXXIV 1634.

- Matthews, John & Caitlin Matthews. The element encyclopedia of magical creatures. New York: Barnes & Noble, 2008.

- Morrison, Elizabeth. Beasts: factual and fantastic. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum; London: British Library, 2007.

- Nishimura, Margot McIlwain. Images in the margins. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum; London: British Library, 2009.

- Paré, Ambroise. The workes of that famous chirurgion Ambrose Parey: translated out of Latine and compared with the French. London: Printed by Th: Cotes and R. Young; anno 1634.

- —– Les oeuures de M. Ambroise Paré, conseiller, et premier chirurgien du roy …: auec les figures & portraicts tant de l’anatomie que des instruments de chirurgie, & de plusieurs monstres : le tout diuisé en vingt six liures, comme il est contenu en la page suyuante. A Paris: Chez Gabriel Buon; 1575.

- Paré, Ambroise; Pallister, Janis L. On monsters and marvels. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; c1982.

- Rāzī, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā (Rhazes). Ninth Book of the Al’Mansuri (Liber Nonus ad Almansorem). Expounded and Commented by Gerard de Solo and Translated into Hebrew by the physician Tobiel ben Samuel de Leiria (of Portugal), Portugal, 1388 translation; 15th century copy, https://uab.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/PHARM/id/1262.

- Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft; Pearson, Edmund Lester; Henry Everett. Frankenstein; or, The modern Prometheus. New York: Heritage Press, 1934.

- Stevenson, Robert Louis; Muller, Hans Alexander. The strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. New York: The Peter Pauper press, 1945?

- Stoker, Bram. Dracula. New York: Grossett & Dunlap; 1931, c1897.

Originally published by The University of Alabama at Birmingham Libraries, Spring 2020, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.