Shifting attention from analysis to synthesis of divine concepts in ancient Rome.

By Dr. Michael Lipka

Professor of Religious Studies

University of Patras

Adoption

The formation of divine concepts was normally conducted in one of three different ways, which were on occasion combined. Either a divine concept was modelled on a foreign equivalent (adoption), or a previously profane concept became divine by the application of cult (deification), or a specific element became emancipated from a divine ‘parent’, thereby gaining separate divine status (differentiation). By contrast, an already existing divine concept could be dissolved (dissolution). In this essay I will deal with conceptualization in the form of adoption.

New gods could be adopted in numerous different ways. Often, initial carriers of new cults were settlers or merchants, who—on their arrivial via Puteoli during the Republic, or via Ostia in the imperial period—brought new gods as part of their merchandise (e.g. Isis). Other carriers were inspired missionaries such as the Greek “dabbler in sacrifices and fortune-teller” (sacrificulus et vates), who introduced Bacchus to Etruria (from where it entered Rome).1

Gods adopted in this way began as private deities and were, as a rule, gradually integrated into the official pantheon. This category of imports includes, for instance, Castor and Pollux (whose temple was dedicated in 484 B.C.).2 One can add Iuno Lucina, whose cult may or may not have been a foreign (Sabine?) import, but whose temple certainly started in Rome as a private foundation at the beginning of the fourth century B.C. and turned into a public cult at some stage in the third.3 Isis, who arrived in Rome presumably in the second century B.C., struggled for more than two centuries before gaining general acceptance in the first century A.D. Sarapis, her divine consort, mentioned in Rome (as possessing a temple?) by Catullus,4 had received his own festival, the Sarapia, by the first century A.D.5 This may point to an acceptance of his cult and to an importance matching that of his popular female counterpart.6 A case very similar to Sarapis is that of Attis. The latter appears to have been unofficially worshipped as consort of the officially recognized Magna Mater in the Palatine sanctuary of the goddess from at least the first century B.C., as is shown by a number of terracotta figurines found there.7 However, the cult of Attis did not become emancipated until the first century A.D., when, starting perhaps with Claudius, a cycle of festivals dedicated to him was introduced.8

While personalized gods were regularly adopted into the official Roman pantheon, abstract divine notions from abroad only rarely received religious attention. The most notable examples of such gods in Rome hail from Greece and were feminine abstract nouns.9 A clear instance is Nemesis, who despite her worship in the centre of Rome, i.e. on the Capitol, did not receive a Latin name (a fact so remark-able, because so rare, that Pliny points it out on two occasions).10 In a similar vein, the Greek goddess Hygieia (as Hygia) was worshipped in Rome alongside Aesculapius, though one may doubt whether she was an official deity.11 The Moerae were called upon during the Augustan Secular Games (though otherwise a cult of them is not attested).12 The building of a temple to Mens (‘Mind’) was decreed after the first Roman defeats against Hannibal in 217 B.C.13 The Greek concept of sofrosúne may have played a role here, as is suggested by the fact that the foundation of the cult of Mens was ordered by the (Greek) Sibylline books and by the popularity of the cult of the goddess in central and southern Italy (where Greek influence was particularly strong).14 One may also consider Concordia (‘Concord’) a concept formed on the notion of Greek homónoia.15 Clark is clearly wrong when she argues for a ‘give and take’ mentality on equal terms in the Hellenistic world, denying a movement of concepts “only towards Rome”. Given the striking ignorance and indifference of the average Greek (which, of course, would not include cases such as Polybius) towards Roman culture, custom and most importantly, language, especially during the period in question (e.g. the Hellenistic period), there can be no doubt that the movement of concepts between Greece and Rome, wherever it existed, was one-sided.16

It often remains doubtful whether a divine concept was actually created using a Greek model as a precedent, or whether an old, independent deity, was eventually identified with a similar divine Greek notion. Mens may be a case in point, for the equation with sofrosúne is not entirely satisfying: apart from the fact that the two terms do not entirely coincide (sofrosúne in Latin would rather be prudentia, while Mens in Greek would rather be noûs), the Greek goddess is not known to have been worshipped in Italy or Greece, nor was a temple built to her anywhere in the ancient world, as far as we know.17 It is possible that Mens was felt to possess a divine dimension even before identification with (and as a consequence partial assimilation to) the concept of Greek sofrosúne. Another case, the abstract goddess Fortuna, had certainly developed into a fully fledged divine entity even before she entered the orbit of Greek Tyche. Her cult in Rome dates back at least to the sixth century, when the cult of Greek Tyche, if extant at all, was still in its infancy; this is quite apart from her rather different functions (fertility, sovereignty and human destiny in the case of the Roman goddess, chance in the case of the Greek deity) and, as far as we can judge, different iconographic foci (e.g., the Roman goddess seated, the Greek goddess standing).18

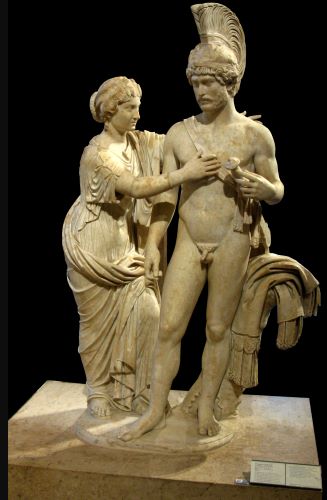

In a few cases, it was not the pre-existence of private cults, but the ruling of Roman officialdom that led to the adoption of a new deity. In these cases, the officials sought to ‘conceptualize’ the foreign deity in Rome by cultic foci in the six constituent conceptual categories. This could be done in a rather superficial manner so as to preserve the essential foreign character of the adopted gods. A case in point is the transfer of Magna Mater from Asia Minor, following a senatorial decree in 204 B.C.

The temple of Magna Mater was officially dedicated in the religious centre of Rome in 191 B.C. Later, no less a figure than Augustus felt proud of having restored it.19 Beyond that, the goddess retained vari-ous and strikingly un-Roman elements of her cult and thus remained foreign to Roman taste, at least until the Augustan period (by which time her cult was increasingly Romanized though). For instance, dur-ing the Republic her high priest and priestess in Rome were Phrygians. The attire worn during religious processions and their musical instruments were markedly un-Roman.20 Similarly, the general cult terminology and the actual cultic hymns as well as the name of the festival dedicated to the goddess were Greek.21 A natural consequence of this was that the participation of Roman citizens in her cult was restricted to the organization of the Megalensia and the performance of the annual sacrifice by the praetor, as well as to the membership of private associations (sodalitates) to honour the goddess by holding sumptuous banquets (which were reserved for the patricians).22 Otherwise, any participation of Roman citizens was strictly forbidden, at least in the Republic (later, these sanctions were relaxed).23 In fact, the lack of Romanization of Magna Mater often earned mockery and contempt by Republican writers.24

The way in which cults were introduced by public authorities will now be illustrated by two cases from very different periods, namely the introduction of Magna Mater at the beginning of the second century B.C. and the short-lived introduction of the god Elagabal at the beginning of the third century A.D. As will become apparent, despite very different historical circumstances the basic pattern remains identical.

1. Space: To begin with Magna Mater, in 204 B.C. the senate passed a decree which provided for the transfer of the baetyl of Magna Mater from Pessinus in Asia Minor to Rome. The senatorial decree determined the erection of a temple for the goddess,25 which was formally dedicated on April 11 in 191 B.C.26 The temple was situated at a prominent spot on the south-western slope of the Palatine. Later (suggestions waver between the first and second century A.D.), Cybele (= Magna Mater) received a second major sanctuary (Phrygianum) on the other side of the Tiber near the site of St Peter, i.e. outside the city walls.27

In a very similar vein, Elagabal received two temples early in the third century A.D. One was situated outside, the other inside the city walls. The extra-mural temple was situated in the suburbs at the eastern flank of the Caelian hill, the intra-mural temple next to the ruler’s residence on the Palatine, where the cult icon, a baetyl, was stored.28 The spatial juxtaposition of the imperial palace and the sanctuary of the god may be compared to that of Augustus’ private residence next to the temple of the Palatine Apollo. The location of the temple of Sol Invictus Elagabal was further marked by a large number of altars built around it.29

2. Time: With regard to temporal foci of the two cults, Magna Mater was transferred from Asia Minor to Rome in 204 B.C., where she was temporarily housed in the sanctuary of Victoria, before she received a temple of her own.30 Both the date of her arrival in Rome (April 4) and of the dedication of her temple (April 11, 191 B.C.) were meticulously recorded in the calendary tradition.31 Similarly, on the occasion of the introduction of the cult in 204 B.C., public Games are mentioned under the name Megalensia.32 It seems more probable than not that these formed an integral part of the foundation decree of the cult, since they appear also as scenic Games in 194 B.C.33 It is clear that in 191, when the temple was dedicated, these Games lasted two days at least (April 4–5).34 Subsequently, the Games were held on an annual basis. Under the Empire, the Games lasted 7 days (April 4–10).35 In marked contrast to our relatively rich documentation of temporal foci of Magna Mater, we are less informed about Elagabal. It is clear, though, that a festival celebrated in high summer was dedicated to the god, a date chosen, no doubt, due to the god’s nature, since he was a representation of the sun-god.36

3. Personnel: As regards the personnel foci of Republican Magna Mater, her actual cult was conducted by both a male and female Phrygian priest (no doubt, authorized by senatorial decree), while the participation of Roman officials was restricted to the performance of sacrifices and the organization of Games. The exotic appearance and apparatus of these priests were an important reason for the partial stigmatization of the cult throughout the Republic.37 Besides this, (emasculated?) followers of the goddess (galli) and their superiors (archigalli) are attested in Rome. Imperial inscriptions make it likely that archigallus was some sort of a priestly office by that time.38 Apart from that, we find other priests (sacerdotes) of both sexes in the imperial period with their respective superiors (sacerdotes maximi, identical with the archigalli?).39 Most of these were Roman citizens; accordingly, it seems that the restrictions placed on the participation in the cult were lifted during the imperial period, though emasculation was still explicitly penalized by Hadrian.40 If we turn to Elagabal again, the most visible personnel focus of the cult was the emperor himself.41 He had become high priest of the god in Emesa when still a boy. After his arrival in Rome in 219 A.D., he did not immediately advertise his priesthood, for reasons of tact. It is only from the end of 220 A.D. that his priestly title appears on coins and inscriptions (on inscriptions sacerdos amplissimus dei invicti Solis Elagabali, on coins with variations).42 Tellingly, when other priesthoods such as that of the pontifex maximus were mentioned in his titulature, they followed that of the new god.43

4. Function: The standard requisite of Magna Mater already in Republican iconography was a turreted crown, interpreted by Lucretius as indicating the protection of cities.44 Such tutelary functions match the historical circumstances under which the goddess was adopted, i.e. the final and decisive phase of the Second Punic War.45 However, this conflict was virtually the last for the next six hundred years to come in which protection of the capital was needed. In compensation, a hypothetical Tojan link of the goddess came to the fore. Initially, the latter may well have been circumstantial,but with the ascent of the Iulii (i.e. alleged offspring of Aeneas) to world power under Caesar it was no doubt exploited for propagandistic reasons.46

Although originally a form of the sun-god, the worship of Elagabal in Rome was marked by a virtual absence of specific functional foci. The god was redesigned by the emperor, as it were, in order to embrace and eventually subdue Roman polytheism in its entirety.47 This explains why the young emperor removed from their ancestral sanctuaries all symbols of traditional Roman polytheism, such as the stone of Magna Mater, the fire of Vesta, the Palladium of Minerva, the ancilia of Mars and “all that the Romans held sacred”, and placed them in his new temple.48

5. Iconography: The iconography of Magna Mater was exceptional in Roman terms, but remarkedly similar to that of Elagabal. The baetyl which represented the goddess had been brought from Asia: an unhewn black stone of hand-size. Apparently, in Arnobius’ day it was displayed in the temple on the neck of an otherwise anthropomorphic statue (oris loco).49 In Augustan literary and visual art, as well as later, the baetyl is replaced completely by the attributes of the goddess, most notably the turreted crown and lions, with or without the actual female figure representing the goddess.50 Like Magna Mater, Elagabal too was worshipped in the shape of a baetyl, i.e. in aniconic form. As in the former case, this posed a problem of recognizibility. The problem was again solved by an iconographic marker, in this case an eagle. The eagle had already accompanied the baetyl of the god in representations from ancient times, as the earliest extant Syrian evidence testifies.51 After the introduction of the cult in Rome, the eagle remained a standard requisite of the Syrian god: it appeared on a figurative pilaster capital from Rome, which may have belonged to the Palatine temple, and also on Roman coins from the period in question.52 In most cases, the eagle was represented in frontal view, with its wings half opened and a wreath in its beak. The depiction resembled the Jovian bird, with the exception of the baetyl, which was normally depicted (at least on Roman representations) behind it. Such an association of the god with Iuppiter was deliberate, since the Syrian god claimed the succession of Iuppiter.

6. Ritual: Three rituals of Magna Mater in Rome stand out. Annually, the followers of the goddess would rally to form a procession in the city, carrying her cult image to the sound of tambourines and flutes, while at the same time begging for alms.53 Interestingly, Ovid mentions a peculiar ritual bath of the cult statue of the goddess in the Almo, a tributary of the Tiber, in the southern vicinity of Rome in connection with the first day of the Megalensia (4 April).54 This ritual may be attested in 38 B.C., but this time, if in fact it is meant, it is an exceptional ceremony performed on the orders of the Sibylline books.55 Later on, perhaps after reforms in the time of Claudius, the washing took place on March 27, and appears thus dissociated from the Games of Magna Mater, but as part of the festive cycle of her consort Attis.56 The third ritual, better known, is the sacrifice of a bull (taurobolium) or ram (criobolium). During the ritual the high priest descended into a pit and was drenched with the blood of the sacred animal which was slain above him.57 These ritual foci of the goddess may be compared to the two rituals of Elagabal described at length by Herodian: firstly, the sacrifice of a hecatomb of cattle and sheep performed daily at dawn, and secondly, the annual midsummer festival, on which occasion the baetyl of the sun-god was carried in a procession through the city to the suburban temple. Simultaneously, chariot races, theatrical performances, and other spectacles were staged.58

To conclude, despite the long period between the transfer of the cult of Magna Mater and that of Elagabal, in both cases the authorities endeavored to conceptualize the incoming god in exactly the same way. The newcomer had to be conceptualized through all six constituent concepts of space, time, personnel, function, iconography and ritual. Though some scholars find this hardly surprising, it discloses a somewhat neglected side of conceptual analysis, viz. the fact that the principles underlying it were in fact timeless parameters, called into service by the respective authorities on different historical occasions in very similar ways. It was not the concept of divinity that changed over time, but the power constellations surrounding and employing it: both the Republican senate and its dubious late-born Syrian surrogate four centuries later realized that there was only one way to conceptualize a foreign god successfully in Rome, i.e. simultaneous conceptualization through all six constituent concepts alike.

A specific form of cult transference is the summoning of a deity from besieged cities (evocatio)59 such as that of Iuno Regina from Veii on the destruction of the city by Camillus in 396 B.C. (forming a new triad with adjacent Aventine temples of Iuppiter Libertas and Minerva?),60 as well as the possible transference of Iuno from Carthage,61 Vertumnus from Volsinii,62 and Minerva from Falerii Veteres.63 In these specific cases (with the exception perhaps of the Carthaginian Iuno), the deity called forth was granted a new temple in Rome. It was thus fully adopted into the official Roman pantheon.64

According to Verrius Flaccus, an evocatio was normal practice in the cases where a city was besieged by a Roman army.65 However, the Augustan scholar does not mention that all such gods were necessarily summoned to the city of Rome itself. Indeed, passages in Festus show that while some rituals were transferred to Rome in the course of the evocatio and conducted as ‘foreign rites’ (sacra peregrina),66 others continued to be performed where they had always been, monitored from now on by Roman pontiffs (sacra municipalia).67 Besides this, an inscription from Isaura Vetus in Cilicia, dating from ca. 75 B.C., suggests that the tutelary deity of the hostile city was simply relocated to a specific area outside the beleaguered town. After the latter’s capture, a temple was erected in the predefined extra-urban area as a new dwelling of the ‘evicted’ deity.68 In the case of the tutelary deities of more important cities, for example Veii and Carthage, the place of repatriation of the deity may have been Rome for propagandistic reasons. On general grounds, however, it is clearly impossible that all tutelary deities of the countless cities conquered by Rome, in the course of her history, were transferred to the capital itself.

Deification

Virtually any physical or abstract entity could be deified, i.e. receive worship of some kind.69 Deification implied that the object of deification had no previous cult. Therefore, any deified object had a potentially profane side to it. The degree of potential profanity depended on the nature of the deified object: impersonal notions (e.g. venti/pietas) never lost it, as long as they were used as mere appellatives (without a divine connotation), while divinized persons might appear with increased divinity after their death (their human characteristics fading in the memory of their worshippers). On the other hand, an impersonal notion, once established as divine, was not as transitory as were divinized individuals. Unlike the latter, it normally possessed a well-defined functional focus. At any rate, all deifications in Rome were in fact partial, with a (new) divine aspect added to a (hitherto) profane notion, rather than replacing it. In analyzing the process of deification, impersonal notions have to be distinguished from individual beings. Both categories are dealt with separately.

To begin with the former, the first step in deifying a hitherto profane impersonal notion was the establishment of a functional focus, as a rule evident from the very name of the notion chosen to be deified. Thus, a Plautan character paid tribute to Neptune and the ‘salty waves’ after his safe return from a sea voyage.70 Clearly, the ‘salty waves’ in this context must have been perceived as (partly) divine, since they are addressed in a prayer alongside Neptune. Their functional focus was naturally felt to be exactly what ‘salty waves’ meant to be, i.e. ‘the sea’.71 In the same vein, the ‘functional’ gods derived their functional foci from the (supposed/reconstructed) etymologies of their names (e.g. Sterculus = ‘god of manuring’, cf. stercus, -oris = ‘manure’). Their ad hoc character was discernible not only by their often transparent etymologies, but also by the frequent variants of their names: thus we find the god of ‘manuring’ as Sterculus alongside Sterculius, Stercutus, Stercutius and Sterculinius, the goddess ‘furnishing food’ as Edulia next to Edula and Edusa etc.72 It is unlikely that in all these cases a flawed manuscript tradition is to blame. More probably, the names had never been fully standardized, and alternative forms continued to circulate. A further step in the same direction can be assumed, when ‘functional gods’ were combined by virtue of functional complementarity. Thus we find Anna Perenna [“goddess of the year operating throughout the year”], Patulcius Clusius [“the god who opens and closes”], Prorsa Postverta [“the goddess that operates from the front and back”] and others.73 It goes without saying that such ad hoc creations rarely survived for long (though Anna Perenna, for example, endured).

The second step in the process of deification was the establishment of spatial foci. The simplest form was an altar or small sacred precinct. For instance, Aius Locutius (Cicero: Aius Loquens), the deified voice (Lat. aio, loqui) which according to lore warned the Romans of the approach of the Gauls in 391 B.C., though manifest only on this occasion, received an altar on the Palatine.74 Futhermore, Rediculus, god of ‘return’ (Lat. redire), had a small sanctuary on the second milestone of the Via Appia, where Hannibal was said to have abandoned his march on the city in 211 B.C.75 Resulting as they did from single historical events, these sanctuaries resembled war memorials rather than spatial foci of a specific deity.

In the most permanent form, impersonal notions received a full-scale temple. Thus, ‘Fever’ (Febris) had a time-honoured temple on the Palatine;76 ‘Concord’ (Concordia) received a temple in 304 B.C.,77 the ‘Storms’ (Tempestates) in 259 B.C.,78 and ‘Piety’ (Pietas) in 181 A.D.79 The establishment of a spatial focus in the form of a temple implied the establishment of foci in other categories, for instance temporal foci to commemorate the anniversary of the temple, personnel foci (from lay administrators to full-time priests), iconographic foci in the form of cult images, and ritual foci in the shape of regular sacrifices offered on the anniversary of the temple.

As a rule, official deification (in marked contrast to private deification) was not an evolutionary process, but a one-time decision manifesting itself in a senatorial decree. Most of all, the decree was concerned with the establishment of a spatial focus, which was normally a temple or a shrine. Prior to such official recognition, there had normally been a long period of ‘silent’ divinization. This phase may have lasted many centuries. Evidence for such initial stages is almost non-existent. This is due to the fact that most divinized impersonal notions were drawn to the attention of ancient writers only when a temple was dedicated to them and they thus began to appear in official written records (most notably the official calendar, where the dedication dates of the official temples were marked). No doubt, in many cases the temple foundation itself was the climax of a long and tortuous development, during which the divine character of the impersonal notion was increasingly, but unofficially, shaped in the common mind.

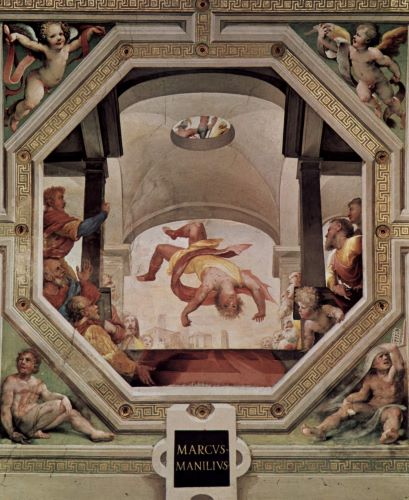

The deification of historical persons has to be distinguished from that of impersonal notions. A vague supernatural nimbus, which might temporarily lead to divine worship, had always surrounded the most powerful in the state. Indeed, important historical figures of the Republic were credited with such divine or semi-divine powers. These include Camillus, Manlius Capitolinus, Decius, Scipio, the Gracchi, and Marius.80 Ad hoc deifications referred to in the writings of Plautus point to the same fact, proving what one would have guessed anyway, that in a comical context a mere mortal could be addressed as a god or even claim divine worship.81 One may also grant that in the case of early historical figures there is no indication whatsoever that the sources, though belonging to a later age, do not reflect the beliefs of the period they pretend to describe.82 Nevertheless, the assimilation of humans to the divine status did not in any way lead to a lasting or premeditated augmentation of the official Roman pantheon, nor indeed to anything remotely comparable to it. For these were no permanent cults of divine concepts, but ephemeral and inconsequential outbursts of public approval; at most, one might say, admiration in a semi-cultic form.

Official deification in Rome can be dated accurately to the period immediately following Caesar’s assassination and culminating in the formal consecration of the deceased dictator by the senate in January 42 B.C. The circumstances leading up to this climax have been adequately analyzed by Weinstock and others and need no further exposition here.83 Whatever stance is taken regarding the exact sequence of events, it is clear that ultimately, the deified ruler secured a well defined position as a divine concept.

Despite the more or less stereotyped procedure of posthumous divinization of the emperor during the imperial period, there seem to have been palpable differences between individual Divi in terms of actual worship. True, on the official plain the divinized emperor was treated exactly like a traditional god, despite certain inconsistencies in practical legal matters (e.g. perjury by the divinized, heritability).84 However, in terms of sentiments and acceptance of divine status, the merits of the emperor towards the senatorial élite and the populace played a decisive role.85 Thus, the deification of Augustus was widely expected in Rome even during his lifetime,86 while that of Claudius was caustically satirized.87 Surprisingly, the deification of such a generally well-received figure as Hadrian had to be forced upon the senate by his successor.88 One has to conclude that, behind the official equality of divine status, there lingered an unwritten hierarchy of popular sympathy towards the divinized, which differed widely according to the social status and personal experience of the worshipper and according to the virtuous character of the dei ed monarch. Needless to say, literature was always more generous in granting divine status to emperors, even while they were still alive.89

Most, but not all emperors were divinized after their death,90 and not all of those divinized were honoured in the same way.91 While close relatives of the emperor could also be consecrated posthumously, some emperors such as Caligula, Nero, Domitian and Commodus, were denied such honours (damnatio memoriae).92 Nor were all emperors convinced of their own future divinization; and even if they were, not all were in a position to convincingly offer themselves as claimants to divinity, especially after dynastic change.93 It follows that despite formal recognition of a divine status, i.e. of the various conceptual foci of imperial divinity, there was no archetype of the ‘divine’ emperor.

The emperor was not officially worshipped in Rome during his life-time, although some emperors, viz. Caligula and Domitian, indulged in being addressed as a god on earth, and no doubt flattered themselves by thinking that they were indeed gods.94 The acts of the arvals make it clear that the living emperor was officially considered merely as guarantor for the well-being of the state, and nothing more.95 No emperor previous to Aurelian at the end of the third century A.D. appears to have been officially labelled ‘god’ in Rome during his lifetime.96 While official terminology and divine attributes were ultimately dictated by imperial taste (modestia), the functional position of the living ruler in the Roman pantheon was not. As guarantor for the well-being of the Roman Empire he was in competition with no one less than Iuppiter himself.97 Not even a critical mind such as that of Vespasian could afford to ignore this functional aspect of the Roman ruler cult.98

Only members of the imperial family were officially deified in the city of Rome. A very rare exception may be Antinous, Hadrian’s young Bithynian lover, who drowned in the Nile in 130 A.D. After his death the youth received divine honours in many parts of the Roman (mostly eastern) Empire.99 In an inscription from Lanuvium dating from 136 A.D. he is clearly portrayed as an official god, since his cult is marked by spatial (temple), temporal (celebration of his birthday), and personnel foci (incidentally, he had no priest, but an official named quin quennalis who was in charge of his cult).100 But this case is exceptional in the West and, after all, is found outside Rome. Despite private devotion to Hadrian’s lover, even in Rome,101 an official cult is not attested and was presumably cautiously banned from the capital by the emperor himself.102

Differentiation

The more important a Roman god, the more likely his various functions were to become emancipated and to be worshipped as separate divine concepts. I shall refer to such derived and emancipated divine concepts as hypostases. In Rome, the process of hypostatization can be neatly demonstrated in the case of Iuppiter. His functions were differentiated according to various concepts, such as ‘space’ as in the case of Iuppiter Viminus (located on and protecting the Viminal hill), ‘action’ as in the case of Iuppiter Fulgur (Iuppiter as the god of lightning), or general ‘qualities’ as in the case of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus. These hypostases are, of course, not mutually exclusive and may occur with various, partly self-contradictory or inconsistent ramifications.103 They are in evidence also for the hypostases of other major gods (e.g. Venus Erycina [‘local’], Iuno Regina [‘functional]’), but naturally, hypostatization was limited to deities of a more general nature. By contrast, gods with more specific competences, even if they were popular and central figures of the Roman pantheon, had no official hypostases. Thus no hypostases of Robigus, Pales, Quirinus, Neptune, not to mention Aesculapius and Ceres, are attested in the official cult. Admittedly, it may often be impossible for us to determine whether a god was simply characterized informally by an attribute, or whether the attribute and divine name actually formed a cult title (therefore denoting a divine hypostasis)—and in the private sphere this difference would have been blurred anyway. It is a qualified guess, however, that in official circles, at least, such a difference did exist (Iuppiter Optimus Maximus was hardly just Iuppiter with two attributes defining his quality as the highest god) and that the indigitamenta or other priestly traditions served here, as elsewhere, to draw a line between what was officially admissible and what was not. So we can conclude that various forms of hypostases existed. The degree of their independence of the hyperstasis can be analyzed by determining their relation to the six constituent concepts of a Roman ‘god’.

Space: A separate temple was the characteristic par excellence of an independent hypostasis, and it was natural to erect temples of hypostases in the vicinity of those of their hyperstases: for instance, in the Republican period we find on the Capitol, in addition to the cult of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus, the cults of Iuppiter Africus, Iuppiter Feretrius, Iuppiter Pistor, Iuppiter Soter (?), Fides (see below) and Vediovis (see below). During the Augustan period, the temple of Iuppiter Tonans was added, followed in the Claudian era by an altar to Iuppiter Depulsor, and under Domitian by a temple to Iuppiter Custos (Conservator).104 Despite the fact that already in the Republican period, important cults of Iuppiter can be located outside the Capitol (e.g. of Iuppiter Stator at the Circus Flaminius, Iuppiter Invictus on the Palatine, Iuppiter Elicius on the Aventine, Iuppiter Fulgur on the Campus Martius),105 the cluster of spatial foci of cults of Jovian hypostases on the Capitol is unlikely to be mere coincidence. In the same vein, we find three spatial foci of cults of distinct hypostases of Fortuna in close vicinity to each other: Fortuna Primigenia, Fortuna Publica Populi Romani Quiritium (both sharing the same temple anniversary, March 25), and Fortuna Publica Citerior in Colle (anniversary, April 5).106 The entire region was called ad tres Fortunas after them.107 Clusters of spatial foci of hypostases, in fact, reinforced the spatial focus of the corresponding hyperstasis.

Time: With regard to temporal foci, the important parameters were the temple anniversaries and the festivals that were characteristic of specific hypostases. For instance, the anniversaries of some temples coincided with days sacred to corresponding hyperstases, thus indicating a close connection: Iuno Regina, Iuno Lucina, Iuno Moneta and Iuno Sospes all had their temples dedicated on the Kalendae of a month (days sacred to Iuno). The anniversaries of temples of Iuppiter Opti-mus Maximus, Iuppiter Victor, Iuppiter Invictus, and perhaps Iuppiter Stator, all fell on the Ides (days sacred to Iuppiter). Exceptionally, Iuno Curritis had her anniversary on the Nonae; and the anniversaries of the temples of Iuppiter Liber, Iuppiter Tonans, and Iuppiter Fulgur fell neither on the Ides nor on any other day sacred to Iuppiter.108 If we turn to festivals, one may point to the Larentalia on December 23, which may have been dedicated to Vediovis (among other deities?).109 More important is the case of Iuppiter Feretrius, who not only had his own temple on the southern peak of the Capitoline, but also his own Games, the Ludi Capitolini on October 15. However, Iuppiter Feretrius may owe his existence to a merger of Iuppiter with another independent deity rather than to a hypostatization of Iuppiter.110

Personnel: Iuppiter Feretrius had his own priesthood, the Fetiales. One may refer also to Fides. The deity was presumably a Jovian derivate and was consequently looked after by the flamen Dialis (see below). When the very nature of the hypostasis prevented its cult from being administered by a priest in charge of the hyperstasis (as in the case of Vediovis, who was connected with the underworld), presumably the pontiffs used to stand in. Apart from practical considerations, avoidance of the creation of new priesthoods in these cases may have been politically motivated. It is plausible to assume that the priests who promoted the differentiation of their deity in order to increase their own religious power and prestige, were naturally the least likely to part with the accrued ritual obligations and privileges this differentiation brought them.

Function: More often than not, the early stages leading to differentiation were marked by fragmentation and/or separation of specific functional foci and their formation into new conceptual units. Thus Fides sprang out of ‘trust’ which formed the basis of ‘oaths’, an age-old functional focus of Iuppiter. ‘Libertas’, the central idea of the Republic and as such guaranteed by Iuppiter, herself became an independent goddess.

Iconography: Iconographic foci could become emancipated from the hyperstasis too, for example the appearance of Vediovis as a young man accompanied by a goat (see below). This was markedly different from representations of Iuppiter, because of Vediovis’ function which was diametrically opposed to Iuppiter’s. After all, Vediovis was a god of the underworld (see below), Iuppiter a god of the upper world. One may refer also to the female Fides (whose late-Republican cult statue is partly preserved)111 as a likely hypostasis of the male Iuppiter, or to the appearance of Iuppiter Feretrius as a flint-stone (silex).

Ritual: Separate ritual foci could determine the independence of the hypostases. This is evident in the two separate vows to Mars Pater and Mars Victor, performed by the same priests within the same ceremony and on the same occasion: the arval brethren used to pledge to each deity a bull with gilded horns upon Trajan’s safe return from the battlefield. Vesta in various forms (Vesta, Vesta Mater, Vesta Deorum Dearumque) receives sacrifices during the same ceremony. The arvals invoke Iuppiter Optimus Maximus and Iuppiter Victor and offer sacrifices to them separately, though within the same ritual.112 Similarly, Macrobius (certainly drawing on a priestly source) records that Ianus could be invoked in seven different forms when a sacrifice was offered to him, no doubt sometimes during the same sacrificial ritual.113

As a matter of fact, only a few cases are attested in which a hypostasis becomes emancipated from its parent god to an extent that would justify its recognition as a new deity in its own right. Not surprisingly, all such cases were connected with the highest god, Iuppiter. These will now be dealt with in greater detail.

It was not by chance that Fides had her temple on the Capitol next to that of Iuppiter.114 The vicinity of the spatial foci of the two cults reflected the complementary functions of the god of ‘oaths’ (Iuppiter) and the goddess of ‘trust’ (Fides).115 Given the fact that a similar local proximity is in evidence for the predecessor of the Capitoline triad (Capitolium Vetus) and the cult place of Dius Fidius on the Quirinal, one may tentatively assume that this closeness was again motivated by complementary functions. Three considerations suggest that both Dius Fidius on the Quirinal and Fides on the Capitol form hypostases of the relevant cults of Iuppiter.

Firstly, etymology. Despite attempts by the ancients to interpret the epithet Fidius as filius (‘son’),116 there is no reasonable doubt among modern scholars that the word is connected to fides (‘trust’).117 Besides, whatever the exact etymology of Dius, there is a consensus among scholars that the word is somehow linked to the semantic field of Iuppiter, either as an adjective meaning ‘bright’,118 or more directly as ‘belonging to Iuppiter’.119 Even the ancient etymologists consistently sensed the link with Iuppiter.120

Secondly, ritual. We now nothing of the cult of Dius Fidius, though we do have important information concerning the cult of Fides on the Capitol, which for the sake of argument may be considered here as forming the pendant to the cult of Dius Fidius on the Quirinal. According to Livy, Numa Pompilius established the custom for a number of unspecified flamines to drive in a two-horse covered carriage to the temple of Fides.121 Latte argued that the term flamines was here employed vaguely to mean sacerdotes.122 Indeed, in the imperial cult, and especially outside Rome, the two terms may be used interchangeably.123 However, there does not seem to exist a single instance of such lax usage in Republican Rome nor, for that matter, in the writings of Livy. The opposite is true: Livy explicitly and in very accurate terms mentions the foundation of the office of the flamen Dialis by Numa.124 Latte’s suggestion does not answer the fundamental question as to which priests were actually meant. For a priest of Fides (‘sacerdos Fidei’) does not seem to be attested anywhere in Rome, and the plural form of the word in the Livian passage would remain a mystery even if there had been one such priest. Hence, we do better to take Livy at his word. In this case, the number of flamines could be approximately determined by the fact that a single two-horse carriage (bigis curru [sing.]) could carry three persons at most. It is then almost compelling to conclude with Wissowa (and others) that the three flamines maiores were meant, with the flamen Dialis likely to be the central figure of the group.125 In other words, if Wissowa is right, the flamen Dialis (and perhaps also the flamines of Mars and Quirinus) was connected to the cult of Fides on the Capitol (and possibly by extension also to the cult of Dius Fidius on the Quirinal), thus establishing a direct link between the priest of Iuppiter and the cult of Fides.

Thirdly, the location of the sanctuary: hypostases, especially those of Iuppiter, display a tendency to cluster around their hyperstasis in spatial terms. One such cluster of spatial foci of the cult of Iuppiter is the Capitol, as I have shown above.

To conclude, both Dius Fidius and Fides were likely to be hypostases of Iuppiter, and felt to be so by the Romans. Their official status is evidenced by the participation of flamines in their (or at least the latter’s) cult and by their public temples. But this hardly means that they were on a par with Iuppiter: for instance, neither was called upon in official contexts as guarantor or protector of oaths. This domain apparently remained reserved to Iuppiter.126

There is no doubt that the name Vediovis is a derivative of Iuppiter, regardless of whether the correct cult title is Vediovis,127 Veiovis,128 Vedius,129 or Vedius Iovis.130 As a derivative, it is clear that Vediovis is younger than Iuppiter. The etymological connection, as well as the erection of a temple of Vediovis in the immediate vicinity of the Capitoline Iuppiter,131 further suggest that the god began his divine existence as a Jovian hypostasis. Besides this, the god was a local concept, for apart from an isolated inscription from the close vicinity of Rome it is attested (and poorly at that) only in the Etruscan pantheon as Vetis/Veive, where, however, it appears to have been borrowed from the Romans.132

Having said that, the name Vediovis is odd. It was not the norm for a god to derive his name from another theonym by means of suffixation. Hence, the reading Vedius Iovis (normally changed to Vediovis) in the basic Laurentinian codex (F) of Varro’s Lingua Latina merits consideration.133 A Jovian hypostasis, specified originally by an attribute vedius, would more effectively explain why some sources repeatedly refer to the god simply as Iuppiter: thus, Livy mentions the latter, where he (or perhaps better his source) reports the foundation of two temples of Vediovis in Rome.134 In the same vein, both Vitruvius and Ovid refer to the god’s temple on the Tiber island as that of Iuppiter.135 Finally, an enigmatic entry in the Fasti Praenestini, according to which the festival of the dead on December 23 (Larentalia) belonged to Iuppiter, would find an explanation in this way (for the chthonic aspect of Vediovis, see below).136

All sources agree that Vediovis (though still connected) was different in nature from Iuppiter. Two interpretations have been put forward since antiquity, both revolving around the interpretation of ve-. According to the first, Vediovis constituted an antithesis of Iuppiter and by extension a chthonic god.137 According to the second, Vediovis represented a ‘small’ (= ‘young’) Iuppiter.138 Though both interpretations are in principle plausible, the former is better supported by the evidence: Vediovis was called upon, alongside Dis Pater and the Manes, as one of the chthonic deities who brought destruction upon hostile cities.139 It was to him that the violator of clientele law was handed over, in order to be killed.140 Similarly, a goat was sacrificed to him ritu humano,141 i.e. in a funeral context.142 An Agonium on May 21, presumably sacred to Vediovis,143 lay midway between the Lemuria and the Canaria, which were dedicated to chthonic deities.144 Indeed, no other Roman god formed a hypostasis on the basis of age, most definitely not in a pantheon in which gods were principally mythless, ageless and without kinship affiliations (factors which alone would have justified such a hypostasis). Furthermore, if there had indeed been a Vedius Iovis as an intermediary form, as suggested above, it would be difficult to appreciate how vedius could have adopted the notion of ‘small’, while the attribute could easily have been interpreted as ve-dius meaning ‘not bright = dark’. Such an etymological explanation would lend further support to the notion that Vediovis was a chthonic deity.

It could be argued that the misconception of Vediovis as ‘small’ Iuppiter was presumably due to the fact that next to his Capitoline cult statue stood the image of a goat, which was identified with Amalthea, the goat that fed the young Zeus with its milk in his Cretan haunt.145 But apart from the fact that the depiction of such niceties of Greek myth are unlikely to have occurred in the case of an old, exclusively Roman hypostasis, the goat itself was apparently felt by the Romans to stand in a patent contrast to Jovian nature. This is why the flamen Dialis was not allowed to touch or even name the animal.146 This means, therefore, that the goat represented the antithesis of Iuppiter and appeared as Vediovis’ sacrificial animal in the statuary group. This, at least, is how Gellius interpreted the scene. It could be parallelled by similar statuary groups of other deities accompanied by their sacrificial animals.147

A special case is the development of Liber from an independent deity into a Jovian hypostasis. Liber appears firmly established in the earliest calendar with his festival Liberalia on March 17. The nature of the festival (a phallus procession) marks him as essentially a fertility and vegetation deity and makes the participation in the festival (and possibly the very existence at this early stage) of his counterpart Libera unlikely (in fact, Liber may originally have been of undetermined sex, like Pales or Ceres).148 Liber’s nature was radically transformed when his cult was conjoined with that of Ceres (again, an old Italian fertility deity, with whom Liber may have entertained earlier cult relations) and that of (the newly-created?) Libera. The triad received a temple on the Aventine in 493 B.C.149 While it is clear that Liber and Ceres, considered separately, were old autonomous Italian gods, the addition of Libera and the formation of the new triad with its own temple was Greek in concept. This is supported by plenty of evidence: for instance, the temple was reportedly erected at the prompting of the Sibylline books,150 it was the first sanctuary to be decorated by Greek artists,151 the priestesses of the triad were Greeks by birth from southern Italy,152 and all cultic terms were Greek.153 The Romans themselves considered the cult a Greek ‘transplant’.154 Most significantly, the constellation of the triad itself, especially the inclusion (creation?) of Libera for that purpose, was modelled on the well known Greek triad of Demeter, Dionysos and Kore.

Once a Greek link was established, Liber could be identified not only with Dionysos, but also with Iuppiter. For it was only a matter of time before Liber (‘free’) was identified with Zeus Eleuther(i)os, the protector of Greek freedom during the Persian Wars.155 This step was taken elsewhere in Italy and in Delos too.156 Regardless of whether political acumen or etymological ignorance served to motivate it, such an identifiation led to the creation in Rome of a new hypostasis of Iuppiter, that of Iuppiter Liber/Libertas. The god received a temple on the Aventine (not a particularly ‘Jovian’ spot) on April 13, a day sacred to Iuppiter.157

Occasionally, gods were differentiated according to sex. This can be illustrated by the existence of pairs of male and female deities such as Liber/Libera, Ceres/Cerus, Faunus/Fauna (Silvanus/Silvana), and Cacus/Caca.158 Where the sources provide relevant information, these pairs are bound by kinship: Libera is said to be the sister of Liber,159 Caca of Cacus,160 and Fauna either the daughter, sister, or wife of Faunus.161 However, the raison d’être of such pairs was not a—non-existent—Roman fondness for divine genealogies, but the complementary, sex-related spheres of their competences (fertility, cattle-raising), although Ceres and Liber may originally have been sex-indifferent nouns.162 It also has to be noted that both partners are never equally prominent. This may well suggest that they did not come into being as pairs, but that one partner was modelled on the other, thereby allowing the lesser party to develop its own iconography. Such a development is in evidence in Rome for Libera (taking over the iconography of Proserpina) and Silvana (Silvanus was generally identified with Faunus).163

It remains hard to determine whether the early sex-oriented differentiation of divine competences was actually a Roman invention or simply a foreign adaptation. There are indications that Faunus/Fauna are Illyrian imports.164 The same may perhaps be true of Liber/Libera,165 unless Libera was simply ‘invented’ on the occasion of the foundation of the Aventine triad (see above). By contrast, Cerus as a correspondent to Ceres appears only in the Salian hymn166 and in a third-century B.C. inscription from the vicinity of Rome,167 and therefore seems to be a Roman product. In the same vein, Caca, forming a pendant to Cacus, has been convincingly interpreted as an older Roman goddess despite her rare and late appearance in the sources. Servius mentions a sacellum consecrated to her which was, one may guess, located in Rome.168

Dissolution

Divine concepts are never static, but are constantly recreated, developed, refined and abandoned. They are unpredictable in terms of their actual development, not in terms of the inner logic of this development. While their future destination is always unknown, the means to arrive there are invariably fixed by the limits set by the process of conceptual derivation. I have tried to analyze the movement towards the formation of divine concepts. In this essay I will discuss the reverse process, viz. their dissolution.

Roman gods were conceptualized by means of conceptual foci. Such foci could become increasingly specific (focalization) or blurred (defocalization). In fact, conceptual focalization can be viewed as the process of gradual conceptualization of a Roman deity, while conceptual defocalization may be considered as tantamount to its gradual dissolution The resulting instability of divine concepts was thus not restricted to any specific period of Roman polytheism. Rather, it was inherent in the conceptual system and a natural response to social and historical changes at all times. No doubt, however, the advent of the imperial cult was an accelerating force towards destabilization.

I have already referred to a patent example of defocalization of a Republican cult: when Quirinus was eventually identified with Romulus, his traditional conceptual foci became blurred, while Romulus received a new, god-like, though perhaps not fully divine, appearance.169

However, it was the imperial cult that contributed most to the defocalization of Republican cults. For, parasite-like, it attached itself indiscriminately to traditional conceptual foci of all kinds of divinity. It occupied the spatial foci of other gods by the erection of imperial images in their precincts, it took over temporal foci through synchronizing temple anniversaries with imperial events. It blurred personnel foci by allowing the combination of traditional and imperial priesthoods in the hands of the same person. It compromised traditional iconography by imitating the physiognomy and attributes of traditional cult statues. Lastly, it took the edge of venerated rituals by copying and deflecting them from their original target deities. In short, no constituent concept of the traditional divinities remained untouched by its surreptitious advance. There can be little doubt, then, that it considerably accelerated the natural process of dissolution of many age-old conceptual foci of Roman gods, while at the same time it cleared the way for the formation of a divine concept with a completely new and powerful set of constituent concepts, which was soon to subvert Iuppiter and Caesar alike, viz. the Christian god.

The continuous focalization and defocalization of concepts were natural and self-regulating processes. Apart from that, cultic foci were on occasion artificially abolished by the Roman authorities. Primary targets were the spatial foci of hostile cults, with the objective of either abolishing them or submitting them to direct public control. It is not by chance that the first regulation of the Tiriolo decree, restricting the cult of Bacchus in 186 B.C., suppressed the cult places of the god. Slightly modified, the same regulation was repeated at the end of the decree, thus laying exceptional emphasis on the spatial aspect.170 Livy confirms the priority of actions against the spatial foci of the cult.171 Besides this, when the senate decided to restrict the cult of Isis and Sarapis in Rome during the first half of the first century B.C., the most important measure (and therefore the only one mentioned by the sources) was the destruction of a temple.172 A similar attack on the spatial markers of the Egyptian gods, viz. a number of altars erected on the Capitol, is mentioned by Varro for 58 B.C.173 On other occasions, we hear of senatorial interventions against the cult in connection with demolition of sanctuaries.174 Furthermore, the importance of space is clearly manifest in the case of emperors who had been publically outlawed (damnatio memoriae). Most notably, of course, they would not be divinized, and accordingly would not receive a temple. After Caligula’s demise, the senate even considered destroying the existing temples of imperial wor-ship in an attempt to annihilate for good all memory of imperial rule.175 However, other measures too served to make the condemned emperor invisible (i.e. non-existent) in spatial terms. For instance, his statues were destroyed or removed from public view. His name or depictions were erased from public monuments (e.g. none of Domitian’s dedicatory inscriptions in Rome remained intact after his condemnation). Most notably, the iconography of his statues was changed and his presence in urban space thus obliterated (see below).176

In the case of condemned emperors, there is good evidence for the abolition of temporal foci too, since their names were purged from the official calendar.177 The Feriale Duranum, dating from the beginning of the reign of Alexander Severus (222–235 A.D.), bears witness to the long-term impact of such purgative measures in the official army calendar: despite the high percentage of days related to the imperial cult, references to those emperors who had not received dei cation (e.g. Tiberius, Caligula, Nero, Domitian) are lacking.178 The symbolic significance of the calendar becomes apparent when Claudius did not allow the day of his enthronement to be celebrated as a holiday, since it was on that day that his predecessor was murdered.179

Besides, public authorities could suppress iconographic foci. In this vein, more than one hundred sculptures of Caligula, Nero and Domitian were ‘remade’ after the emperors’ death. In other words, their characteristic physiognomy was changed to avoid any resemblance to the disdained rulers. This process of reconfiguring unwanted representations of emperors reached a peak in the first century A.D. and reemerged again in the third. Apparently, its first victim was Caligula.180

Finally, ritual: the Bacchanalian decree forbade any secret ritual foci and granted the performance of public rituals only after permission by Roman authorities. Furthermore, restrictions were placed on the number and gender of participants in the rituals.181 In a similar vein, Augustus and Agrippa intervened in cultic actions directed towards Egyptian gods, by expelling them outside the pomerium (though not prohibiting them entirely).182

Naturally, state intervention did not turn against all adherents of illicit cults in the same way. Those most involved, i.e. the priests or more generally personnel foci, were affected first. The Tiriolo decree, regulating the ban on the cult of Bacchus at the beginning of the second century B.C., excluded men from the priesthood of Bacchus and prevented the election of masters or vice-masters among the Bacchants, apparently a blow against the collegial character of the group.183 More generally, magicians were restricted in their activities by Roman legislation such as that found already in the Twelve Tablets and later on in Sulla’s law passed in 81 B.C. against murderers and those who wrought harmful magic (lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficiis).184 Punitive measures, above all expulsion and death, were directed against any type of magician, both during the Republic and under the Empire.185

Among the many attempts by the authorities to restrict specific divine concepts, none was more notorious and ultimately unsuccessful than the attacks launched against the Christians. Here the authorities ran into two difficulties. On the one hand, it was not at all easy for them to establish with certainty the adherence of a suspect to the Christian faith, because the only bond that tied one Christian to another was joint prayer in conjunction with the temporal focus of Easter, and neither of these two elements was easy to prove. In fact, unless a Christian confessed to his faith, his or her adherence to the Christian god could be demonstrated only ex negativo: ideally, a Christian was someone who would not sacrifice to the emperor and the traditional gods even under the threat of death.186 But this criterion was weak and insufficient, as soon as a defendant actually ignored the Christian dogma of the incompatibility of the simultaneous worship of God and pagan gods.

The second problem Roman authorities encountered was the fact that given the dearth of conceptual foci of the Christian god, there was precious little left to control. Daily prayers and a belief in salvation via resurrection were beyond the reach of Roman officialdom, and spatial foci or priests who could be hold responsible were non-existent. It is then fair to say that it was the essential lack of major conceptual foci of the Christian god that made him uniquely resistant to his persecutors.

Chapter 2 (117-146) from Roman Gods: A Conceptual Approach, by Michael Lipka (Brill, 04.30.2009), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license.