Nacht und Nebel stands as one of the most revealing examples of how a modern state can weaponize administrative structures to enforce disappearance.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Politics of Disappearance in the Nazi State

The decree known as Nacht und Nebel took shape on December 7, 1941, when Adolf Hitler authorized a secret directive permitting the disappearance of civilians suspected of resistance in occupied Europe. Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel signed the order on behalf of the German Armed Forces High Command, formally instructing military and police authorities to remove targeted individuals from their communities and transfer them quietly into the Reich for proceedings before special courts.1 The decree’s language instructed that detainees were to be transported under cover of night and fog, a phrase drawn from German literary tradition but repurposed to signal a deliberate strategy of erasure. It fostered uncertainty among the occupied populations because those taken vanished without confirmation of arrest, trial, or death.

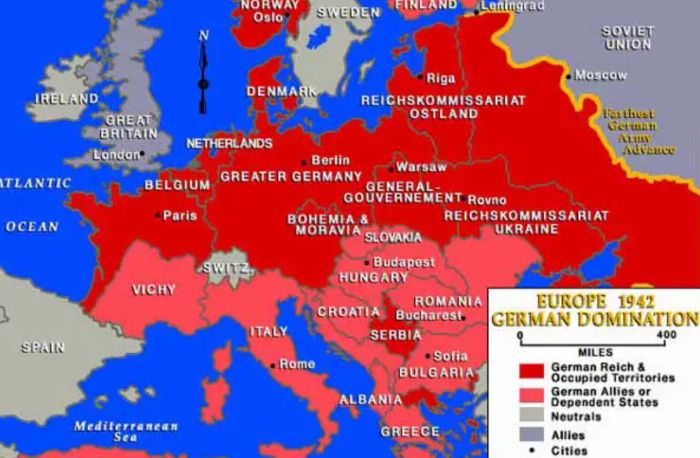

The policy emerged at a moment when the Nazi state was expanding its reach into every domain of political and social life across occupied Europe. Civilian resistance movements in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands had begun to disrupt German occupation, and the Wehrmacht demanded more forceful methods to restrain activities that traditional military courts judged too visible or too limited in effect.2 By authorizing a system that removed individuals from all public accounting, the decree offered a mechanism to bypass established legal norms and to transform detention into an instrument of psychological control. It was not simply an extension of earlier security policies. Instead, it introduced a procedural model that combined secrecy with administrative rigor, a combination that allowed disappearance to become a standard tool of governance within a growing authoritarian system.

Allied observers struggled to comprehend these missing civilians in the early years of the war. Reports compiled by governments in exile and confirmed through the interrogation of German officials after 1945 revealed that the disappearance of detainees was intentional and not a byproduct of the war’s dislocation.3 The absence of information served the policy’s purpose by creating anxiety among communities and by severing the legal and personal ties that might have constrained the actions of occupation authorities. The Nazi state understood this effect, and the Nacht und Nebel decree institutionalized disappearance as a means of securing political order.

The origin, implementation, and legacy of Nacht und Nebel therefore demand examination not only for their historical significance but also for the insights they offer into the operation of coercive power. In an era when debates about the scope of executive authority continue in the United States under President Trump, the historical record of enforced disappearance provides a stark example of the dangers posed when legal structures are subordinated to political expediency. While the circumstances of modern governance differ sharply from those of the Third Reich, the logic of secrecy and procedural evasion embodied in Nacht und Nebel remains a critical reference point for evaluating how states manage dissent, control information, and regulate the boundaries of legitimate authority.

Origins of Nacht und Nebel: Ideology, Military Pressure, and Legal Strategy

The emergence of Nacht und Nebel (NN) in late 1941 reflected a convergence of military frustration, ideological ambition, and administrative experimentation within the Nazi state. German forces in Western Europe faced growing resistance activity that disrupted transport, sabotaged supply lines, and challenged the occupation’s authority. Field reports submitted to Berlin throughout 1941 emphasized that conventional judicial procedures were producing outcomes that the Wehrmacht regarded as too lenient or too visible, outcomes that did not generate the deterrent effect commanders sought.4 The High Command therefore looked for a method that removed suspects entirely from local jurisdictions without leaving a public record of their disposition.

The ideological environment shaped how this new mechanism was conceived. Hitler’s government had already normalized extraordinary measures against perceived enemies, and the concentration camp system had become a central tool for managing political opponents since 1933. By 1941, the expansion of German rule across the continent encouraged a more aggressive framework in which civilians accused of resistance could be treated as subjects outside ordinary legal protections.5 Keitel’s decree aligned with this orientation by asserting that those who opposed German authority in the occupied territories threatened the security of the Reich itself. This framing justified the use of special measures that departed sharply from prior military law.

Bureaucratic dynamics also played a role. The German occupation apparatus involved overlapping authorities that included the Wehrmacht, the SS, and various civilian agencies. Each sought influence over security policy, and the resulting institutional competition fostered innovation in coercive techniques.6 NN emerged partly from this environment. The directive created a procedure that relied on the military for arrest but transferred detainees into a system managed largely by the SS and the Reich Ministry of Justice. Its success depended on the cooperation of these bodies, which found in disappearance a tool that advanced their respective goals: the Wehrmacht gained a mechanism to suppress resistance activity, while the SS expanded its authority over detainee management.

The legal structure of the decree reveals how the Nazi state adapted existing frameworks to achieve political ends. Keitel’s order did not abolish formal judicial processes. Instead, it redirected detainees into special courts that operated outside the ordinary military system. These courts were characterized by extreme secrecy, limited procedural safeguards, and rulings that were not publicly reported.7 The decision to relocate detainees to the Reich further ensured that local populations would have no access to information about trials or sentences. This separation from the occupied territories severed any remaining links between detainees and their communities, which fulfilled the policy’s aim to remove not only individuals but also the social effects of their resistance.

International law provided no meaningful constraint. The 1907 Hague Convention specified rules for the treatment of civilians under occupation, yet the Nazi state regarded these provisions as subordinate to its broader political objectives.8 Resistance was interpreted not as a civilian offense but as an act of hostility against German authority, and the legal protections afforded to civilians were therefore dismissed as inapplicable. Nacht und Nebel crystallized this interpretation by formalizing a procedure that ignored established norms while maintaining the appearance of administrative order. The policy’s origins thus reflect a synthesis of ideological conviction, institutional rivalry, and legal distortion that allowed the Nazi state to convert disappearance into a routine instrument of governance.

Mechanisms of Disappearance: Transfer, Secrecy, and Administrative Control

The practical operation of NN depended on a coordinated system that concealed every stage of a detainee’s removal from the public sphere. Arrests were carried out primarily at night, an approach intended to minimize observation and to generate uncertainty within targeted communities. German occupation authorities often withheld documentation during these seizures, and families were provided no formal acknowledgment that an arrest had taken place.9 This initial moment of disappearance was central to the policy’s strategy because it created the conditions under which further secrecy could unfold without challenge from local institutions or relatives seeking information.

Once detained, individuals were transported to Germany under procedures designed to sever communication and eliminate any traceable record. Transport orders instructed that detainees be moved in small groups to avoid detection, and German officials were directed not to disclose destinations or expected arrival times.10 These transfers frequently involved extended periods during which detainees received no explanation for their movement or legal status. The effect of this uncertainty was to isolate detainees psychologically while ensuring that communities in the occupied territories could not assemble evidence of the policy’s operation.

The decree further required that detainees be removed from all ordinary channels of correspondence. German authorities confiscated personal items, prevented letter writing, and prohibited families from sending inquiries once transfers had taken place.11 The absence of communication was not an incidental feature but a procedural requirement. It denied detainees the opportunity to assert their legal rights and prevented families from pursuing information with local occupation offices or the International Committee of the Red Cross. This isolation distinguished NN prisoners from other detainee categories whose whereabouts, while controlled, were not entirely concealed.

Administrative protocols supported this structure of secrecy by dividing responsibilities between military and civilian agencies. After initial arrest by occupation forces, detainees passed into the custody of the Reich Ministry of Justice or the SS, depending on the nature of the alleged offense.12 Special courts evaluated their cases, but these proceedings took place under strict confidentiality rules that prohibited public reporting. Records were maintained internally, yet they were deliberately shielded from the traditional judicial system. The result was a hybrid legal environment in which bureaucratic form existed but public accountability did not.

The concentration camp system absorbed many NN detainees once their cases were processed. Camps such as Natzweiler-Struthof, Dachau, and Mauthausen maintained specific intake categories for NN prisoners that prohibited disclosure of their presence.13 Camp registers often listed NN detainees under coded designations, a practice that made verification of their fate extraordinarily difficult for families and postwar investigators. The camp environment intensified the secrecy of the decree because death, transfer, or illness could occur without any external notification. This layer of concealment transformed disappearance into a prolonged condition rather than a single act.

The secrecy of Nacht und Nebel relied on the collaboration of officials at every level of the occupation and camp systems. Compliance required regular communication between military commands, judicial administrators, and camp personnel, yet all such exchanges were internal and inaccessible to the public.14 This administrative coherence allowed the decree to function despite its inherent illegality under international norms. By establishing a closed circuit of information, the Nazi state ensured that detainees remained invisible to those outside the system. The mechanisms of disappearance therefore reflected not only the brutality of the policy but also the bureaucratic sophistication that enabled its implementation.

Nacht und Nebel within the Camp System: Administration, Mortality, and Labor

The integration of NN detainees into the concentration camp system revealed how disappearance operated through physical confinement as well as administrative concealment. Once special courts or judicial authorities issued their decisions, many detainees were transferred into camps that were already functioning as multifaceted instruments of punishment, labor, and terror. Camp personnel received explicit instructions that NN prisoners were to be categorized separately from other inmates.15 This designation confined them to a status in which their presence was known only to internal administrative offices and prohibited from all external communication. The classification thus extended the logic of the decree into the daily practices of camp governance.

Conditions for NN detainees varied across the camp network, but several consistent patterns emerged. Camps Ravensbrück became significant sites for NN imprisonment, and their environments exposed detainees to extreme deprivation. Natzweiler, for example, held a large proportion of NN prisoners and was known for its high mortality rates linked to forced labor, inadequate nutrition, and harsh disciplinary regimes.16 The camp’s isolation in the Vosges Mountains contributed to the invisibility of its prisoner population and made it a preferred site for detentions involving secrecy. While NN detainees were not formally sentenced to death, the conditions they faced created a substantial risk of mortality.

Labor assignments played a central role in the experience of NN prisoners. Many were deployed to quarries, construction projects, and industrial worksites connected to the SS economic apparatus.17 Camp administrators tasked with filling labor quotas drew heavily from NN populations because their legal isolation reduced the likelihood of external inquiry into their treatment or survival. The labor itself was often dangerous, and access to medical care was limited. This pattern reflected how the broader concentration camp system converted detainee categories into flexible labor resources, regardless of the nominal judicial purposes these categories were meant to serve.

Death within the NN population was frequently concealed through coded entries or incomplete documentation. Camp registers recorded deaths without providing information about cause or prior legal status, which hindered postwar efforts to identify victims.18 In some cases, NN detainees who died in custody were listed under pseudonyms or numerical designations that obscured their identities even from internal camp offices. The secrecy surrounding deaths reinforced the original purpose of the decree by ensuring that families and authorities outside Germany remained unaware of the detainees’ fate. This concealment formed part of a broader strategy that linked bureaucratic control to the eradication of personal identity.

The administrative management of NN detainees demonstrated the degree to which the camp system could adapt to new categories of prisoners without altering its underlying structure. Camp officials integrated NN procedures into existing routines of registration, labor assignment, and discipline, while maintaining the heightened secrecy that the decree required.19 This combination of ordinary camp administration and specialized restrictions enabled the Nazi state to preserve the appearance of procedural order while implementing a policy that violated fundamental legal norms. Through its incorporation into the camp system, NN transformed disappearance from an act carried out at the moment of arrest into a sustained condition that shaped every aspect of detainee life.

International Law, Resistance, and Allied Responses

The international legal implications of Nacht und Nebel became apparent soon after the decree’s implementation, although the policy’s secrecy initially prevented Allied observers from grasping its full scope. Civilians were disappearing from Belgium, France, and the Netherlands without trial records or notices of transfer, and governments in exile struggled to determine whether detainees had been executed, deported, or imprisoned under unknown conditions.20 Diplomatic reports collected in London and Washington pieced together partial accounts based on scattered testimonies from escapees and intercepted German communications. These early assessments noted a pattern of systematic removal that violated established norms governing occupation but lacked the detail necessary to articulate formal charges.

Resistance movements encountered the effects of the decree directly. Local networks attempting to track missing members found their inquiries met with silence from German commands, which refused to confirm whether arrests had taken place.21 The disappearance of activists weakened organizational cohesion by creating uncertainty about who had been captured and whether compromised individuals might be undergoing interrogation. This uncertainty forced resistance groups to adjust communication structures and to adopt stricter internal controls. The policy thus achieved one of its central aims by destabilizing social and political networks that posed threats to German authority in the occupied territories.

As the war progressed, more comprehensive evidence reached the Allies, particularly through captured German documents and intelligence assessments that confirmed the existence of a directive authorizing secret transfers to the Reich.22 Legal analysts in Britain and the United States evaluated the decree in relation to the 1907 Hague Convention, which outlined protections for civilians under occupation. Their findings concluded that NN procedures violated multiple articles requiring transparency in judicial proceedings and humane treatment of detainees. The absence of notification, the concealment of trial outcomes, and the removal of detainees from their home territories contravened principles that had been foundational to prewar international law.

These legal evaluations shaped the postwar prosecutorial framework. During the Nuremberg proceedings, the Nacht und Nebel decree became significant evidence in the indictment of senior German officials, particularly Wilhelm Keitel, whose signature on the directive established his direct responsibility.23 Prosecutors argued that the decree demonstrated premeditated intent to eliminate judicial protections for civilians and to institute a system that relied on fear and uncertainty as mechanisms of control. The tribunal cited the policy as an example of how the Nazi state manipulated administrative procedures to facilitate crimes that could not be justified under any interpretation of international law.

The reactions of occupied populations after liberation underscored the human consequences of the decree. Communities sought information about missing relatives, only to discover that many had died in custody or been dispersed among camps without documentation.24 Efforts to reconstruct the identities and fates of NN victims required collaboration between Allied authorities, survivor groups, and national governments, and the process revealed how deeply the policy had fractured social networks. These postwar inquiries emphasized that the harm inflicted by disappearance extended beyond individuals to entire communities. In bringing these cases into legal and historical visibility, the Allies confronted the broader challenge of addressing a policy designed to erase the very evidence of its operation.

Memory, Testimony, and the Politics of Postwar Reckoning

The aftermath of Nacht und Nebel revealed how a policy built on disappearance complicated the processes of remembrance and accountability. Survivors who returned to their homelands faced the challenge of explaining experiences that had deliberately been hidden from view, and their testimonies became critical sources for reconstructing the policy’s implementation.25 These accounts confirmed patterns of secrecy noted by Allied investigators, but they also highlighted how uncertainty had shaped the psychological experience of detainees whose identities had been suppressed by administrative design. The absence of formal records made individual stories essential for understanding the human dimensions of the decree.

National governments confronted a similar problem. Efforts to locate missing civilians required laborious searches through fragmented German documentation, surviving camp registers, and testimonies gathered by postwar commissions.26 Many families learned that relatives had died in custody without any official record of trial or sentence. Governments attempted to recognize NN victims as a distinct category within postwar compensation frameworks, yet the lack of documentation often hindered these claims. The policy’s emphasis on secrecy had succeeded in erasing traces that might otherwise have supported legal recognition, and the consequences of this absence persisted long after the war ended.

Historians faced methodological challenges in reconstructing the experiences of NN detainees because the surviving documentation offered only partial insight into the workings of the decree. German authorities maintained internal records, but these records were incomplete and were often coded in ways that obscured the status of NN prisoners.27 Scholars therefore relied on a combination of judicial documents, camp archives, and survivor testimonies to piece together a coherent narrative. The result was a historiography that emphasized both the bureaucratic sophistication of the policy and the human stories that illuminated its effects. This dual focus became central to understanding how disappearance operated within a modern authoritarian state.

The policy’s legacy influenced memory politics in Western Europe. In France, efforts to incorporate NN victims into national commemorative frameworks intersected with broader debates about collaboration, resistance, and the meaning of wartime suffering.28 Belgian and Dutch initiatives followed similar patterns by attempting to integrate disappearance into the narrative of occupation while also addressing the gaps created by the absence of documentation. These national debates revealed how the policy had fractured collective memory by severing individuals from the public record. Without clear documentation, communities struggled to articulate the full scope of loss.

In Germany, postwar reflection on the decree unfolded more slowly. Early narratives focused primarily on military defeat and reconstruction rather than on the systematic disappearance of foreign civilians.29 As scholarship expanded and survivors’ testimonies became more widely available, the decree emerged as an example of how ordinary administrative procedures had been adapted to serve violent ends. Its examination contributed to broader discussions about the nature of state power under National Socialism and the ways in which bureaucratic systems facilitated human rights violations. This emerging recognition underscored the importance of transparency and legal oversight in preventing similar abuses.

The global significance of NN extended beyond Europe. Human rights advocates and legal scholars increasingly cited the decree when analyzing later cases of enforced disappearance in Latin America, the Middle East, and other regions.30 The policy demonstrated how a modern state could use administrative procedures to produce invisibility, and its reception in international law informed the development of treaties addressing enforced disappearance. By examining the policy’s history, scholars and policymakers highlighted the necessity of safeguarding judicial transparency and limiting executive authority, concerns that resonate in contemporary debates about state security in the United States and elsewhere.

Conclusion: State Power and the Lessons of Disappearance

Nacht und Nebel stands as one of the most revealing examples of how a modern state can weaponize administrative structures to enforce disappearance. The decree’s design rested on the premise that secrecy itself could be a tool of governance, capable of shaping behavior in occupied territories without requiring large-scale public violence.31 By removing individuals from all visible legal processes, the policy redefined the boundaries of state authority and demonstrated how bureaucratic mechanisms could be adapted to undermine established legal norms. The success of the decree depended not only on coercion but also on the efficiency and cooperation of agencies that transformed disappearance into a persistent condition.

The policy’s legacy underscores the profound human consequences that follow when legal structures are subordinated to political objectives. Families experienced prolonged uncertainty that extended far beyond the moment of arrest. Communities struggled to rebuild networks disrupted by the absence of those who had been removed. Scholars and investigators encountered gaps in documentation that limited their ability to reconstruct individual histories.32 These effects illustrate how disappearance inflicts damage that is both immediate and enduring. They also highlight the role of transparency and oversight as essential safeguards against abuses that flourish when state actions cannot be scrutinized.

The broader significance of Nacht und Nebel becomes apparent when placed within global discussions about enforced disappearance and the limits of executive power. Human rights frameworks developed after the war, including conventions addressing enforced disappearance, have drawn on historical cases to establish legal protections designed to prevent similar abuses.33 These frameworks emphasize the importance of accountability, the right to information, and the need to restrict the capacity of states to detain individuals in secrecy. The lessons derived from the decree therefore extend beyond its specific historical moment and inform contemporary debates about state security and civil liberties.

In the present political environment, including ongoing debates in the United States under President Donald Trump about the scope of government authority, the history of Nacht und Nebel provides a critical point of reference.34 It illustrates how secrecy, justified as a security measure, can erode legal protections and undermine public trust in governmental institutions. The decree’s legacy challenges governments to maintain transparency and uphold procedural safeguards even in times of perceived crisis. By examining Nacht und Nebel within both its historical and contemporary contexts, it becomes possible to understand how the mechanisms of disappearance operate and why vigilance remains necessary to prevent their reemergence in new forms.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Directive of December 7, 1941, in Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, vol. 3 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946), Document 833-PS.

- Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich at War (New York: Penguin, 2008), 241–244.

- Michael R. Marrus, The Nuremberg War Crimes Trial, 1945–46 (Boston: Bedford Books, 1997), 39–41.

- Evans, The Third Reich at War, 241–247.

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler, the Germans, and the Final Solution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 189–193.

- Mark Mazower, Hitler’s Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe (New York: Penguin, 2007), 172–177.

- Nikolaus Wachsmann, KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015), 381–384.

- Donald Bloxham, Genocide on Trial: War Crimes Trials and the Formation of Holocaust History and Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 17–19.

- Evans, The Third Reich at War, 245–248.

- Wachsmann, KL, 383–385.

- Wachsmann, KL, 385–387.

- Mazower, Hitler’s Empire, 178–181.

- Sarah Helm, Ravensbrück: Life and Death in Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women (New York: Nan A. Talese, 2014), 226–231; Harold Marcuse, Legacies of Dachau (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 54–56.

- Bloxham, Genocide on Trial, 20–22.

- Wachsmann, KL, 381–384.

- Wachsmann, KL, 402–405; Helm, Ravensbrück, 226–231.

- Evans, The Third Reich at War, 253–257.

- Marcuse, Legacies of Dachau, 55–59.

- Mazower, Hitler’s Empire, 178–183.

- Bloxham, Genocide on Trial, 23–24.

- Evans, The Third Reich at War, 249–252.

- Marrus, The Nuremberg War Crimes Trial, 41–44.

- Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, vol. 3, Document 833-PS.

- Wachsmann, KL, 387–389.

- Wachsmann, KL, 387–391.

- Bloxham, Genocide on Trial, 37–39.

- Marcuse, Legacies of Dachau, 55–60.

- Henry Rousso, The Vichy Syndrome (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 231–236.

- Marrus, The Nuremberg War Crimes Trial, 88–92.

- Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 384–389.

- Evans, The Third Reich at War, 241–249.

- Wachsmann, KL, 387–392.

- Bloxham, Genocide on Trial, 37–41.

- Marrus, The Nuremberg War Crimes Trial, 92–95.

Bibliography

- Bloxham, Donald. Genocide on Trial: War Crimes Trials and the Formation of Holocaust History and Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Evans, Richard J. The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin, 2008.

- Helm, Sarah. Ravensbrück: Life and Death in Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women. New York: Nan A. Talese, 2014.

- Kershaw, Ian. Hitler, the Germans, and the Final Solution. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

- Marcuse, Harold. Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933–2001. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Marrus, Michael R. The Nuremberg War Crimes Trial, 1945–46. Boston: Bedford Books, 1997.

- Mazower, Mark. Hitler’s Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe. New York: Penguin, 2007.

- Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression. Vol. 3. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946.

- Rousso, Henry. The Vichy Syndrome. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

- Wachsmann, Nikolaus. KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.09.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.