By Cecily Hilleary

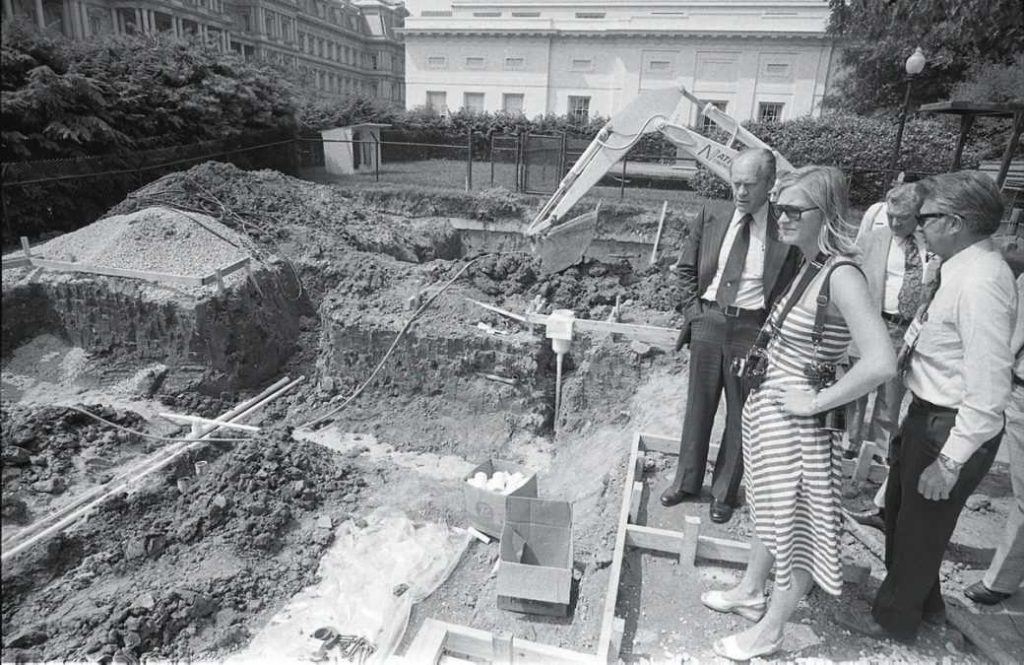

During his time in the White House, Former President Gerald Ford decided to build an outdoor swimming pool. National Park Service archaeologists examined the site of the dig, which is standard operating procedure when anything is constructed on national parkland. They found Native American artifacts, evidence of an indigenous presence in Washington dating back millennia.

“Very little is known about the earliest Native Americans in Washington, say from 12,000 to 16,000 years ago,” said Ruth Trocolli, city archaeologist for the District of Columbia ( D.C.), who works to identify and preserve Washington’s archaeological heritage. “D.C. developed far too quickly for those kinds of sites to be easily identified today.”

The city sits at the junction of two major rivers, the Potomac and the Anacostia, which flowed even at the peak of the Ice Age.

“The location was hot, hot, hot for Native Americans, primarily because there was water available all year round and because of the kind of resources you get where water flows all year,” Trocolli said.

Once a year, when the shad ran upriver from the Chesapeake Bay, Natives from tribes in surrounding areas would come inland to what is today the Nation’s capital and camp on the shores.

“They would catch and process the fish, probably drying it, and while everyone was together, they probably had parties and feasts and weddings and funerals and spiritual ceremonies,” said Trocolli.

At the time Europeans first began exploring the Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River region, three Native confederacies had come to power: The Piscataway, who dominated nearby southern Maryland; the Susquehannock in Pennsylvania; and the Powhatan confederacy in Virginia.

The people of Nacotchtanke, associated and allied with the Piscataway, were first noted by Captain John Smith on a 1612 map of the region. Later Anglicized to “Anacostia,” Nacotchtanke was an Algonquin term for “town of traders,” according to 19th Century Algonquin educator William Wallace Tucker.

Nacotchtanke comprised as many as five villages with a total population of fewer than 400—80 of them “able men,” according to Smith. The main, fortified village sat on the east bank of the Potomac River at the point where it branches into the Anacostia River, making it an ideal spot for canoe trade with other tribes living in the Potomac River basin. It also was a good vantage point for spotting the arrival of their upriver enemies.

A second village, unnamed, was located along the Potomac to the northwest of the city, and a third, Nameroughquena, on the Potomac’s west bank in present-day Arlington, Virginia. In addition, remains of settlements and campgrounds have been found scattered the full length of both rivers.

Smith did not describe the people of Nacotchtanke, but eyewitness accounts of other coastal Algonquin groups give a good idea of what they looked like and how they lived.

“The natives are of tall and comely [attractive] stature, of a skin by nature somewhat tawny, which they make more hideous by daubing, for the most part, with red paint [from the bloodroot plant] mixed with oil, to keep away the mosquitoes,” Jesuit priest Andrew White wrote of the Yaocomico in 1634.

The men did not have facial hair, he said, but painted the lower half of their faces black, giving the impression of beards.

They wrapped deer hide around their waists and wore hides as cloaks. Some wore strands of glass beads around their necks or a copper fish ornament on their foreheads, and White says they also tied their long hair “in a fashionable style” to one side.

“Their weapons are bows and arrows, two cubits [one cubit equals the length of a man’s forearm] long, pointed with buck horn or a piece of sharpened flintstone,” wrote White. “They direct these with so much skill that at a distance, they can shoot a sparrow through the middle.”

The Yoacomico, like the Powhatan of Virginia, slept in high-ceilinged longhouses built by lashing saplings together into a large dome, covered with bark or rushes. They slept communally around a central fire; a large hole at the top of the building gave light and allowed the smoke to rise. Chiefs, called werowances, and other ranking officials were segregated into private apartments and slept on elevated beds.

According to White, the Yoacomico recognized a single god but didn’t worship him in any formal ceremony. However, they did recognize an evil spirit they called “Okee,” and they tried to keep him happy.

About a thousand years ago, the Native Americans in Washington transitioned from being hunters/gatherers and settled down as farmers.

Nineteenth Century archaeologist Samuel Proudfit surmised that the Nacotchtanke may have used the flat land around the U.S. Capital building as a field for interplanting corn, beans and squash, known by many tribes as the “three sisters.”

Archaeologists have uncovered the remains of rock quarries in Rock Creek Park, a 1,755-acre wooded area that bisects the city. Nacotchtanke workers moved cut stone to nearby workshops where they chiseled it into arrow points, knives, axes and cooking vessels.

Just blocks from the White House, archaeologists in the 1980s found a burial pit containing the cremated remains of an adult woman who died at least 1,200 years ago. She was buried with artifacts, including a comb carved from a deer antler, a wooden head and textiles woven from grass.

A half century after the arrival of European settlers, the population of Nacotchtanke had begun to dwindle. Some moved to nearby Analostan Island. Others died from disease or merged with the larger Piscataway tribe. Some may have been sold into slavery, and still others likely married and assimilated into colonial culture.

By the time slaves laid the cornerstone of the White House in 1792, the Nacotchtanke people were gone. But archaeologists like Ruth Trocolli continue to find the artifacts Washington’s earliest settlers left behind.

Originally published by Voice of America, 01.16.2020, under a Government Public Domain license.