This global policing of the past should concern anyone who believes in democratic ideals. For history is not a settled ledger.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Memory on the Witness Stand

In classrooms, courtrooms, and legislatures from Texas to Warsaw, history is increasingly on trial. What once may have been the domain of academic disagreement or political debate is now subject to criminal sanction, curriculum bans, and weaponized nostalgia. The past has always been vulnerable to manipulation, but in our own time, it is being disciplined more aggressively than ever, and not only by authoritarian regimes.

The trend spans the globe. In the United States, state-level education boards push for textbook revisions and laws that sanitize slavery and whitewash systemic racism. In Eastern Europe, governments pass “memory laws” to enforce nationalistic versions of wartime narratives. In India, populist efforts reshape medieval history to align with Hindu nationalist visions. Even in liberal democracies, historical discomfort is increasingly framed as disloyalty. The past, in short, is being governed with remarkable precision.

But history does not lend itself easily to control. It is layered, messy, and fundamentally contested. To police it is not merely to challenge fact; it is to strike at the fragile space where identity, power, and truth intersect.

Redefining Patriotism in the American Classroom

The culture wars in the United States have long touched education, but in recent years, history itself has become a central battleground. Dozens of states have proposed or enacted legislation aimed at restricting how educators discuss racism, colonialism, and gender. These measures often frame critical historical perspectives as divisive or anti-American.

Take, for example, the wave of “anti-CRT” (Critical Race Theory) laws that began sweeping through state legislatures after 2020. While CRT as a graduate-level legal theory is not taught in K-12 schools, the term has become a catch-all for virtually any curriculum that foregrounds racial injustice. In Texas, lawmakers passed House Bill 3979, banning the teaching of certain concepts related to privilege and systemic oppression. Florida’s “Stop WOKE Act” goes further, penalizing employers and educators who promote materials deemed to cause “guilt” or “anguish” based on race.

These laws do not simply censor content. They send a message that only certain versions of the American story are acceptable, those that affirm national pride without confronting its costs. Teachers report increased fear of reprisal, parents are mobilized to monitor lesson plans, and textbook publishers recalibrate content to fit political mandates. As a result, students receive an increasingly curated vision of the nation’s past.

Yet the irony is profound. To deny students an honest reckoning with American history is to deprive them of the very tools of civic engagement and critical thought that democracy demands.

Eastern Europe’s Battle for Narrative Sovereignty

In countries like Poland and Hungary, history has become a matter not just of national pride but of national law. These governments argue that memory must be protected against what they see as slander, often meaning any suggestion of local complicity in historical atrocities.

Poland’s 2018 amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance criminalized claims that the Polish nation was complicit in Nazi crimes. While the law was later softened under international pressure, its effect lingers. The state continues to promote heroic narratives of Polish suffering during World War II while downplaying episodes of collaboration or antisemitism. Scholars and journalists who challenge this account face lawsuits, harassment, and professional risks.

In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has orchestrated a cultural campaign to rehabilitate figures like Admiral Miklós Horthy, whose regime allied with Nazi Germany. The government promotes a version of Hungarian history that centers victimhood and resilience, brushing aside darker chapters. Statues go up, textbooks change, and critics are silenced. The past becomes a tool not for learning, but for loyalty.

These efforts are often couched in the language of sovereignty. National memory is cast as a cultural asset to be defended from foreign distortion. But the cost of this defense is steep. Once history is placed under official guardianship, it ceases to be a field of inquiry and becomes an instrument of ideology.

Global South: Revising Empires, Reclaiming Voices

Memory politics are not confined to the West. In the Global South, debates over historical revision often take the opposite shape — not whitewashing crimes, but insisting they be named. Former colonies push back against sanitized imperial histories that have long dominated global narratives.

In South Africa, students of the #RhodesMustFall movement demanded not only the removal of statues but the decolonization of university syllabi. In India, the past is being fiercely contested in new ways. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has worked to rewrite school history books to emphasize Hindu contributions and minimize the Muslim Mughal era. The goal is not simply educational. It is political and theological.

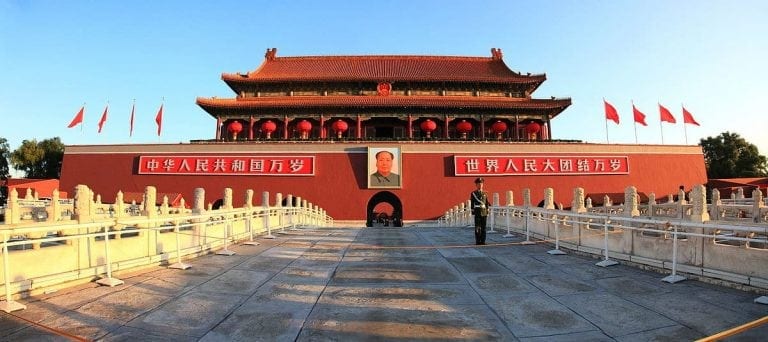

China offers yet another model. The Communist Party tightly controls historical discourse through censorship, surveillance, and ideological campaigns. The memory of Tiananmen Square is forbidden, and schoolchildren grow up with a heavily curated view of twentieth-century China. Here, history is not revised; it is erased.

In each case, history functions as a battleground where political legitimacy is forged. But the battle lines differ depending on whether a regime seeks to reclaim dignity, assert dominance, or suppress dissent.

When History Hurts: The Fear of Collective Shame

Underlying these global crackdowns is a shared anxiety: that confronting history honestly might weaken the nation’s fabric. The fear is not new. Societies have long avoided reckoning with shameful chapters, whether through denial, minimization, or myth.

But the intensity of the current backlash speaks to a deeper unease. In an age of disinformation and polarization, many fear that historical nuance is a luxury the public can no longer afford. Instead, governments seek simple stories with clear heroes and villains, even if those stories are false.

And yet, mature civic identity cannot be built on myth alone. Nations, like individuals, must learn to hold contradiction, to sit with discomfort, to speak the unspeakable. Germany’s model of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, or “coming to terms with the past,” remains one of the few examples of a country facing its crimes with institutional honesty. It is not perfect, but it proves that national memory can be a site of healing rather than denial.

The alternative, historical suppression in the name of patriotism, breeds not unity but fragility. It turns history into an echo chamber and civic dialogue into a monologue.

Conclusion: Defending the Right to Remember

What is at stake in these memory wars is not just the past, but the very idea of history as a shared pursuit of understanding. When governments dictate historical truth, they erase not only facts but the freedom to ask questions. They replace inquiry with allegiance, education with indoctrination.

This global policing of the past should concern anyone who believes in democratic ideals. For history is not a settled ledger. It is a living, evolving conversation. To restrict it is to silence voices that may yet hold essential truths. We cannot protect the future by falsifying the past. What we can do, what we must do, is insist on the right to remember, to question, and to learn, no matter how uncomfortable the truths may be. In this way, history remains not a tool of power, but a measure of it.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.18.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.