Originally published by Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, 08.29.2017, Newberry Library, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Introduction

The second global war of the twentieth century, World War II (1939-1945) began when Adolph Hitler’s Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. For the first two years many in the U.S. thought the country should remain uninvolved. But war was declared after Japan’s attack on Hawaii’s military base, Pearl Harbor, on December 7th, 1941. Ultimately, the two warring sides were the Axis Powers––Germany, Italy, Japan, and other countries––against the Allies––Britain, the United States, France, and others. The worldwide Depression of the previous decade had now been replaced with a vast contest between fascist aggression on the one hand and the defense of democracy on the other. For this reason, many still regard WWII as a “good” or “just” war.

Besides Europe, battlefronts existed in such far-flung locales as North Africa, Asia, the North Atlantic, and the South Pacific. WWI had been unprecedented in the killing of soldiers because of the introduction of machine guns, tanks, planes, and poison gas. WWII now involved large-scale assaults on civilians––the Soviet Union suffered the most––resulting in tens of millions of deaths. It remains the deadliest conflict in human world history. But America’s experience of WWII was very different than populations in Europe and elsewhere. No battles or civilians were killed on the American mainland, though families endured thousands of military casualties. Instead, the distant war was experienced mainly through media and popular culture, making its study crucially important.

In the middle of the twentieth century, most of the popular media were in print form: newspapers, magazines, books, maps, and the like. Thus, the pictorial means by which most people engaged news and information about the war were through text, illustration, and photography. Posters delivered visual and textual information in a visually impactful and public manner. They were used for patriotic purposes, to maintain morale, to warn people (of espionage, of sharing war secrets), for recruitment, for rationing and for the sale of War Bonds, certificates that directly funded the war. Publishing firms produced all manner of magazine stories, advertising, and sheet music related to the war. Hollywood produced diverting or patriotic movies, often accompanied by newsreels that sensationalized news of the war. Radio allowed audiences to experience the war even more vividly. In President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous radio “Fireside Chats,” he spoke in a relaxed and candid manner directly to Americans at home, giving them a sense of involvement in the war effort. This period also saw the rise of “Big Bands” that played “Swing” music for a new dancing craze. In terms of fashion, clothing styles were generally conservative, reflecting the economizing of the war era. The flamboyant “Zoot Suit,” however, favored by young African American and Latino men, gave its name to race riots in Los Angeles in June, 1943.

Newspaper and metal drives, “Victory” gardens, and rationing (gas, rubber, fabric, shoes, food, etc.) contributed to the nation-wide effort to direct materials to the military. Through activities like these, the home became a site where family members were encouraged to do their part to help win the war. Popular culture was enlisted to do the same. The government projected an image of an ethnically integrated military—there was still considerable segregation—where each group contributed to the national war effort. Overall, in American popular culture in this period, a bright optimism often masked the darker realities and sacrifices of war. Late in the war, however, Life magazine’s photographs of dead American soldiers and graphic pictures from Nazi concentration camps shocked readers.

President Truman’s decision to drop atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (August 6th and 9th, 1945)—to decisively end the war and demonstrate American power—meant that World War II had brought about the nuclear age, and with it a new “Cold” War.

News and Information about the War

As in our distant wars today, Americans during WWII were eager to learn about developments and locations. To this end, the popular press published a wealth of newspapers, magazines, and books. Lavishly illustrated volumes like Pictorial review of world war two: a pictorial summary of the war to date… provided a great deal of visual and textual information. Besides maps and photographs of military bases and locales, they also provided images of Allied leaders.

Pictorial magazines were both visually rich—providing much space to photographs and illustrations—and extremely popular. Life magazine, bought by Henry Luce in 1936 and transformed into a premier, enduring photography-based magazine, was ubiquitous in American homes and businesses during World War II and after. Its arresting pictures—the magazine’s text was merely captions to them––often helped shape public opinion about the war.

Homefront audiences were particularly interested in news and information about their soldier’s day-to-day life. Receiving mail was a big event for soldiers. Often illustrated with funny scenes, postcards were extremely popular during WWII, and companies like Curt Teich provided thousands of different examples. Besides bringing news from home, the quantity of mail a soldier received could affect the way soldiers viewed each other, as seen here. The comic illustrator Ray Walter drew many such postcards in a zany style in the first half of the twentieth century.

Representing the Soldier

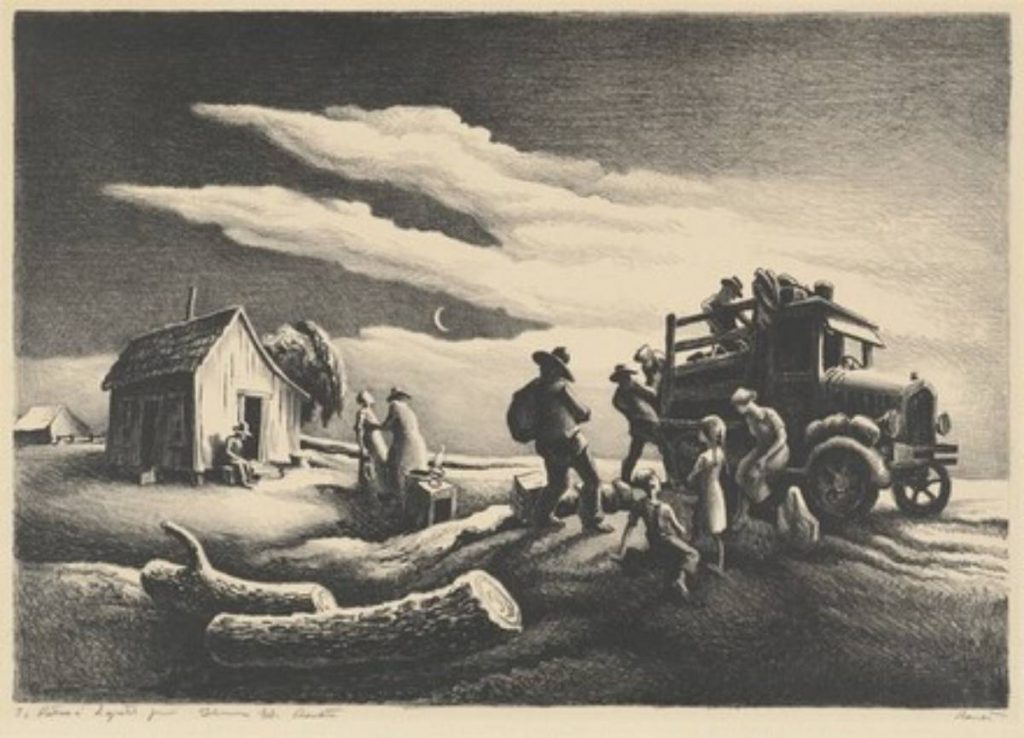

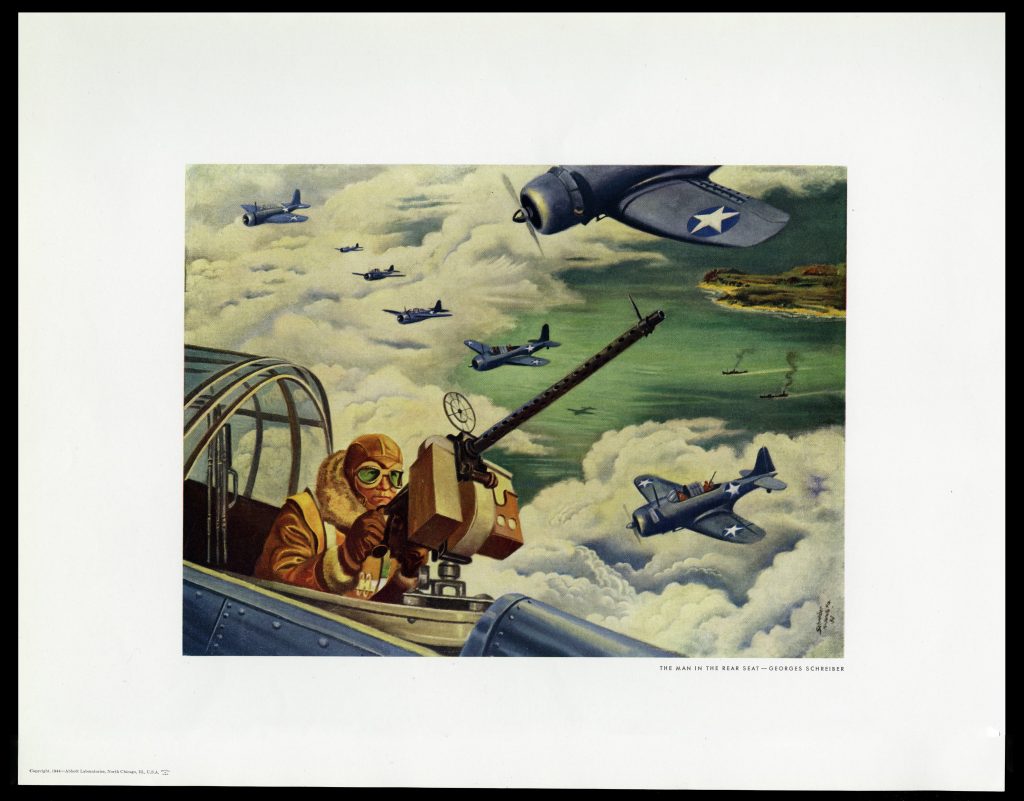

Much of the popular visual culture of the WWII era was devoted to depictions of the American serviceman. Not surprisingly, soldiers were most often represented as energetic, handsome, and for the most part, white. Private companies like Abbott Laboratories sponsored artists, illustrators, and journalists to create visual materials that supported the war effort. Renowned American artists made the drawings and paintings from which these frameable prints were copied.

Political cartoons of the time were often patriotic. In the image pictured here, a steel smelting pot at left (marked “U.S.A”) pours out a wide variety of foreign surnames representing the multi-ethnic makeup of the armed services. Illustrating a “Melting Pot” vision of America, the lettering in the sky reads, “Descendants Of Many Lands Fighting For America, THEIR Country.

Bill Mauldin (1921-2003), a soldier himself, was a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who became famous for his “Up Front” cartoons about military life. His repeating characters “Willie and Joe” are scruffy, dispirited infantrymen enduring the frustrations of war.

The government itself produced pamphlets and publications that documented all aspects of the war effort, including diverse populations serving in the military. Publications like Indians in the War were meant to demonstrate how diverse was the war effort in America. However, the authors and photographers could not always avoid dealing in persistent stereotypes, as seen in the difference between the title page, which shows a traditional Native American ritual, and the sober military portraits inside.

Though often segregated in the military, African Americans played conspicuous and important roles during the war. Written by a black journalist and politician, the war-era pamphlet The Negro in the War (back then, “negro” was considered a polite term) speaks to the reasons why blacks have been mistreated in American society. The author explains how blacks were still expected to serve their country. The section “Things You Can Do” suggests the reader “Try to see that the Negroes in your community have the same opportunities for work, home life, and recreation that are open to white citizens” (p. 32)

The Homefront

Because none of the battles of WWII were fought on the American mainland, people in this country experienced the war from a distance. They kept abreast of news through the media, and tried to help in the war effort by purchasing war bonds, participating in rationing, and of course sending their beloved family members to serve in the military.

Pictorial magazines—a mixture of news, human-interest stories, advertising, and pictures–were ubiquitous during the war. The Saturday Evening Post was one of the most popular magazines of the WW-II era and beyond. Well-known illustrators like Norman Rockwell were regular contributors. Its stories and pictures were oriented to middle-class American families, and much of the war-related popular culture was expressed in its pages.

Victory Gardens were home gardens in which families could raise and conserve their own food and also lower the price paid by the government for food for the military. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt famously planted one on the White House grounds. The word “victory” was applied to just about anything linked to the war effort at this time. Advertisers also used the modifier to help sell their products.

During the war, the government depended on contributions by average citizens to help fund the war effort. This often took the form of war bonds. The large, color, photographic image of a weeping boy in “Buy War Bonds: Third War Loan,” was meant to generate sympathy and contributions. The medal the boy wears and the captain’s hat he holds suggests his father died a war hero.

Gender and War Culture

World War II was a totalizing war, meaning that all the resources of a country—including those who participated in it—were utilized. Because of the scale of WWII, and because production—making armaments, weapons, ships, vehicles and the like—was so important to the outcome of the war, women were now asked to become factory workers. Besides maintaining homes and families, they now found employment in factories and offices directly engaged with the business of war. The character “Rosie the Riveter” was a popular media character, first painted by illustrator Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) for Saturday Evening Post. Young, healthy, and patriotic, she came to represent the strong, determined woman who now did work previously reserved for men.

During the war, women could also serve in the military, though not in combat. Written shortly after the war by two women authors, the book While So Serving (1947) celebrates the contributions of female sailors of the Naval Reserve called WAVES (“Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service”). The pictures and text, however, while showing the stages in a Wave’s tour of duty, repeat stereotypical notions of femininity.

The women shown in the poster “Be a Cadet Nurse: The Girl with a Future” are meant to represent African Americans––though they remain racially ambiguous––and the title suggests that service as a Cadet Nurse offers a more productive future than they might otherwise have had.

Engaging the Enemy

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, there was great anger and mistrust of the Japanese. Calls for retaliation appeared frequently in popular culture. The lyrics of traditional sheet music—which could be played and sung in homes and concerts—were sometimes bellicose, as in “Mow the Japs Down,” which was written by a local Chicago high school.

Most visual culture materials during the war focused on how to contribute to the war effort. In Jean Carlu’s poster, “Give ‘Em Both Barrels,” a man holds a rivet gun, used in manufacturing war vehicles (ships, tanks, and airplanes); it resembles the machine gun the soldier shoots below. One of the more artistic war-time posters—Carlu was a French graphic designer––the image and text suggest that factory production is just as effective as engaging the enemy on the battlefield.

Some people were ambivalent about the way the Japanese in this country were treated. The American western landscape photographer, Ansel Adams (1902-84), known for his lovely pictures of National Parks, made dignified portraits and internment camp pictures of Japanese Americans. Many of these people were legal citizens—entire families in some cases––who were removed from their homes in California after President Roosevelt’s notorious Executive Order number 9006.

Legacy: The Nuclear Age

When the war ended, the map of the world was different, millions were dead, and nuclear bombs had been invented and dropped. The Allies had swept east through Europe after the D-Day Landings (June, 1944); the Soviet Army attacked Germany from the west. The division by different nations of Germany’s capitol, Berlin, reflected the mounting suspicion between the global superpowers of the Soviet Union and the US.

Because nuclear weapons were new and not well understood, the American government sought to understand its devastating effects. The official report The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki includes many maps and photos of the extraordinary devastation of the bomb to buildings and streets rather than to human victims. Images like this would often be reproduced in the years after the war.

Published within months of the dropping of the atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima on August 6th, 1945, Hersey’s book Hiroshima (1946) tells the stories of six survivors, and gives readers a vivid account of the dire effects of nuclear war. The book was so popular that it has never gone out of print. The images in this later edition were made by Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000), an important African American modernist artist. Projects like this one demonstrate that artistic imaginings of the war were as powerful as documentary photographs.

Selected Sources

- Dawn Ades (et al.). Art and Power: Europe under the Dictators, 1930-1945. 1995.

- Monica Bohm-Duchen. Art and the Second World War. 2013.

- Julie Brock, Jennifer Dickie, Richard Harker, Beyond Rosie: A Documentary History of Women and World War II. 2015.

- Robert Henkes. World War II in American Art. 2001.

- Andrew J. Huebner. The Warrior Image: American Culture from the Second World War to Viet Nam. 2008.

- George Roeder, Jr. The Censored War: American Visual Experience During World War Two. 1995.

- The Stars and Stripes: Newspaper of the U.S. Armed Forces in the European Theater of Operations. Newberry Library’s holdings: May 17, 1943–Oct. 13, 1945.

By Dr. Mark B. Pohlad

Assistant Professor of History

DePaul University