Poverty in early America wasn’t an aberration but a persistent and structured feature of colonial and early national life.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Poverty in early America was a pervasive yet unevenly understood phenomenon shaped by a constellation of factors: economic systems, geographic circumstances, labor structures, social hierarchies, and colonial policies. While modern poverty is often framed in terms of systemic inequality and socio-economic exclusion, early American poverty was experienced and addressed in profoundly different ways. From the earliest colonial settlements through the Revolutionary era, poverty was not only a matter of economic deprivation but also of moral judgment, social control, and institutional development. This essay explores the structural and cultural underpinnings of poverty in early America, considering how colonial economies created and sustained poverty, how poor individuals survived, and how the emerging American society responded to economic marginality.

The Economic Foundations of Poverty in Colonial America

Poverty in colonial America was rooted in the economic systems inherited from Europe and shaped by the unique circumstances of the New World. The transference of English mercantilist principles to the American colonies ensured that wealth remained concentrated among a privileged few, while the poor were expected to serve as a laboring class without upward mobility. The colonies functioned within a broader Atlantic economy that prioritized resource extraction, cash crops, and trade, particularly with England. This structure limited the development of a diversified economy that could support widespread prosperity among colonists. Even in the more egalitarian-seeming New England colonies, scarcity of land and resources coupled with strict inheritance laws led to the marginalization of many, particularly second and third sons who had little opportunity to acquire property of their own.1 Thus, poverty became a structural and often intergenerational phenomenon, reinforced by both policy and custom.

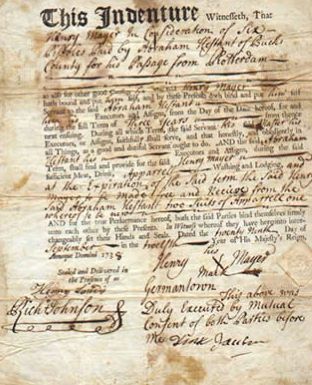

The availability of land was initially seen as a remedy to European poverty, offering the possibility of economic independence. However, as colonies matured, land became increasingly consolidated into the hands of wealthy elites and absentee landowners. In the Chesapeake and southern colonies, large plantations dominated the economy and made the acquisition of small plots prohibitively expensive for poorer colonists.2 Additionally, the labor-intensive nature of crops like tobacco and rice ensured a reliance on enslaved Africans and indentured servants, both of whom occupied the lowest rungs of the economic ladder. For many indentured servants, the promise of land or wages at the end of their servitude proved illusory, as they emerged from their contracts without resources or viable prospects for independence.3 This system effectively created a cyclical poverty trap that ensured a steady supply of cheap labor for the colonial elite.

Urban centers like Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston saw the emergence of new forms of poverty tied to wage labor and fluctuating market demands. These cities developed rapidly in the 18th century, attracting artisans, sailors, dockworkers, and migrants, many of whom found themselves subjected to irregular employment and economic instability.4 The volatility of maritime trade, dependence on transatlantic commerce, and periodic downturns exposed these workers to sudden bouts of unemployment and destitution. In contrast to rural poverty, which was often concealed by geographic isolation, urban poverty was visible and increasingly treated as a public problem requiring regulation and relief. City officials responded with poor laws, almshouses, and workhouses modeled on English precedents, further institutionalizing the divide between the laboring poor and the propertied classes.5

Race and class intersected sharply in the southern colonies, where the development of racialized slavery created a tiered labor system that subordinated both enslaved people and poor whites. While slavery offered planters a stable, hereditary labor force, it simultaneously devalued free labor and limited opportunities for non-elite whites. Poor white farmers, particularly those in the backcountry, lived in precarious conditions with little access to markets or capital.6 Despite their hardships, they were often recruited into systems of social control that preserved the racial hierarchy, ensuring their allegiance to planter elites despite their economic marginalization. Free Blacks, where they existed, faced severe restrictions on land ownership, employment, and mobility, exacerbating their poverty and rendering them perpetual outsiders in the colonial economy.7 In this way, the economic foundation of colonial poverty was not only a matter of wealth distribution but of legal and cultural exclusion.

By the eve of the American Revolution, colonial society had hardened into a complex hierarchy with poverty deeply embedded in its economic and social order. The Revolution would challenge many old institutions, but it would not erase the legacy of economic marginality. Instead, it would usher in new questions about the relationship between poverty and citizenship, labor and liberty. Yet the foundational structures that had produced poverty in the colonial period (land inequality, coerced labor systems, economic dependence on distant markets, and social exclusion) remained largely intact.8 The economic roots of poverty planted in the colonial era would continue to shape the American experience for generations.

Labor, Class, and the Creation of Economic Marginality

Labor in early America was not merely an economic necessity—it was a defining factor in the creation and maintenance of social class. The colonial labor force was stratified along lines of freedom, skill, race, and origin, which resulted in entrenched forms of marginalization. One of the most significant components of early American labor was indentured servitude. Many English, Irish, and German migrants arrived in the colonies by selling years of their labor in exchange for passage across the Atlantic. While some succeeded in transitioning to landownership, a vast number finished their terms impoverished and landless, finding themselves in precarious economic conditions that forced them into lifelong dependency as tenant farmers or wage laborers.9 The exploitation inherent in the system—long hours, corporal punishment, and legal constraints—positioned these servants at the edge of colonial society, tolerated for their usefulness but often regarded as socially inferior.

The shift from indentured labor to racialized chattel slavery in the late seventeenth century further redefined the colonial labor hierarchy and intensified economic marginality. The introduction of lifetime, hereditary slavery not only created a permanent underclass of enslaved Africans but also depressed the value and bargaining power of free laborers, particularly poor whites. As wealthy planters amassed labor forces and land, small farmers and laborers found themselves pushed to the economic periphery.10 For African Americans, enslaved and free, this marginality was absolute, enforced by law, violence, and custom. Free Black laborers in northern colonies often worked the lowest-paying, most unstable jobs, barred from skilled trades and land ownership by racially discriminatory statutes.11 In the South, the existence of free Black laborers was more tenuous, with many subject to re-enslavement, vagrancy laws, and restrictions that reinforced their exclusion from the colonial economy.

The rise of artisan labor in urban areas created a new but limited space for class differentiation. In cities like Philadelphia and Boston, artisans and journeymen formed the backbone of the local economy, producing goods for both domestic use and export. These workers, however, remained vulnerable to fluctuations in supply and demand and often lived on the edge of poverty.12 As urban populations grew and competition for labor intensified, wages stagnated while living costs rose, fostering resentment and class consciousness among workingmen. The eighteenth century witnessed the rise of proto-labor movements and mutual aid societies among urban workers, early signs of a working-class identity emerging within the rigid confines of colonial class structures.13 Yet this growing self-awareness did little to dismantle the structural forces that kept the majority of laborers dependent on elites for economic survival.

Gender further complicated labor and class in early America. Women’s work—both paid and unpaid—was essential to colonial economies but consistently undervalued and largely invisible in formal labor records. Women labored as domestic servants, seamstresses, laundresses, and midwives, often in precarious, informal arrangements that denied them the protections or recognition afforded to men. Widows and single women were especially vulnerable, with few legal rights to property or contract labor.14 Moreover, enslaved women endured the dual burdens of forced reproductive labor and economic exploitation, their bodies commodified for both fieldwork and human reproduction. These labor dynamics ensured that poor women—white, Black, and Indigenous—occupied the most marginal positions in colonial society, their economic dependence reinforced by legal, social, and familial constraints.

Class formation in early America was both fluid and rigid, fluid in the sense that new opportunities occasionally allowed individuals to ascend, yet rigid due to systemic structures that preserved elite dominance. Wealth was concentrated among landowners, merchants, and high-ranking officials who used political power and patronage to secure their economic interests.15 Meanwhile, poor laborers, whether rural farmhands, indentured servants, urban journeymen, or enslaved people, were systematically excluded from the mechanisms of wealth generation and political influence. Class became not merely a matter of income or occupation but of institutional access—who could vote, own land, inherit property, or petition government. In this context, economic marginality was not an accident of fortune, but a product of colonial policies and cultural attitudes designed to maintain hierarchy and control.

Women, Children, and the Gendered Nature of Poverty

In early America, poverty was not merely an economic condition but a deeply gendered experience shaped by the legal and cultural norms of the colonial and early republican periods. Women’s access to economic resources was sharply limited by coverture, a legal doctrine inherited from English common law that subsumed a married woman’s legal identity under that of her husband. As a result, married women could not own property, enter contracts, or control their own wages, making them economically dependent regardless of class.16 Widows and unmarried women, while technically more autonomous, often faced economic instability, especially if they lacked male relatives or dowries. Poor women, especially those in urban centers or working as domestic servants, were more susceptible to exploitation, wage theft, and housing insecurity.17 Their labor was essential to the colonial economy, yet largely invisible in official records, further obscuring the full scale of gendered poverty.

Childhood poverty in early America was likewise closely linked to the gender and marital status of mothers. Children born out of wedlock or to poor single mothers often faced institutional neglect or removal to almshouses and orphanages, where conditions were harsh and survival uncertain.18 In urban settings, poor families frequently relied on the labor of children for survival, pushing boys and girls alike into apprenticeships, domestic service, and street vending from a young age. While apprenticeships were theoretically a pathway to skilled work and stability, they often masked exploitative relationships where children labored long hours for little reward and remained vulnerable to abuse. Female children, in particular, were channeled into domestic roles that offered little long-term security.19 The early American state provided limited mechanisms for poor relief, and what aid existed was often contingent on moral scrutiny, especially for mothers, whose poverty was seen as evidence of moral failure rather than structural disadvantage.

The sexual division of labor also exacerbated the vulnerability of poor women and children. Women’s work was often confined to the household or to “informal” sectors of the economy—laundering, midwifery, childcare, spinning, and sewing—which paid poorly, lacked stability, and received little societal respect.20 For enslaved women, the conditions were even more extreme: they were expected to perform backbreaking agricultural labor while also bearing and raising children who would themselves be considered property. Enslaved mothers had no legal claim to their children, who could be sold at any time, intensifying both their poverty and emotional trauma.21 These structural conditions ensured that gendered poverty was both multigenerational and deeply racialized, affecting Black, Native, and white women differently but systematically.

The intersection of gender, poverty, and moral judgment played a central role in the formation of colonial poor laws. Public relief for poor women, particularly single mothers, was often administered through local parishes or town officials and came with invasive oversight. Women seeking assistance were frequently required to prove their moral fitness, which could include demonstrating chastity, sobriety, and industriousness.22 In New England, “warning out” practices, legal tools used to expel newcomers who might become public charges, were disproportionately applied to single women with children. These laws not only reinforced economic precarity but also social stigma, entrenching a view of poor women as deviant rather than deserving. The few institutions that did exist to care for impoverished women, such as almshouses, tended to be punitive in nature, seeking to reform rather than support them.

Despite these barriers, women often created their own informal networks of survival. Mutual aid among poor women, whether through kinship, church affiliations, or neighborhood cooperation, provided crucial, if limited, support.23 Enslaved and free Black women shared labor, food, and caregiving in ways that helped mitigate the brutality of poverty, even as their communities faced constant surveillance and disruption. Similarly, Indigenous women, though increasingly marginalized by settler colonialism and displacement, maintained communal practices of resource sharing that resisted the individualism and commodification of European economies. Yet these grassroots systems were fragile and constantly under threat from economic downturns, war, and legal changes. The gendered nature of poverty in early America thus reveals a society in which systemic inequalities were reinforced by law, labor practices, and cultural expectations, and borne most heavily by women and children.

Charity, Public Welfare, and the Response to Poverty

In early America, the response to poverty was rooted in a complex blend of religious obligation, civic responsibility, and social control. Inspired by English precedents such as the Elizabethan Poor Laws, colonial governments adopted local systems of poor relief, typically administered at the town or parish level. These systems sought to distinguish between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor, providing aid selectively to those deemed worthy (widows, orphans, the elderly, and the infirm) while punishing idleness and perceived moral failings in others.24 Aid came primarily in the form of outdoor relief—direct assistance to individuals within their own homes, or through the use of poorhouses and workhouses, which imposed strict labor requirements in exchange for subsistence. This form of public charity was deeply moralistic, premised on the belief that poverty was often the result of personal vice or laziness rather than systemic deprivation.25

Private charity operated alongside public welfare, often administered through churches, benevolent societies, and philanthropic individuals. In Puritan New England, for example, charity was seen as a religious duty, one that bound communities together under shared moral expectations. Congregations organized collections for needy members, and ministers frequently preached the virtue of almsgiving.26 However, even private charity reflected social hierarchies and judgments. It was common for donors to monitor the behavior of recipients, and aid could be withdrawn if moral conduct was questioned. Wealthy women played a particularly visible role in these networks, founding orphanages and almshouses and organizing “visiting societies” that surveyed the homes of the poor to assess their worthiness.27 These early charitable organizations both helped and policed the poor, reinforcing social norms under the guise of benevolence.

Poorhouses became more common in the eighteenth century as populations grew and traditional parish-based aid became insufficient. These institutions were intended not only to shelter the impoverished but also to reform them through discipline and labor. Residents, including children, were expected to work for their keep, producing textiles, performing domestic tasks, or farming communal land.28 Yet conditions were often harsh, and poorhouses quickly acquired reputations as places of last resort. Critics noted that such institutions tended to warehouse rather than uplift the poor, subjecting them to indignities and separating families.29 Nonetheless, they represented an important shift in the colonial mindset: from charitable relief as a moral obligation of the community to institutional management of poverty as a social problem.

The American Revolution introduced new strains on colonial welfare systems and provoked debates about the proper role of government in addressing poverty. The war created a surge in widows, orphans, and disabled veterans, stretching the limits of both public and private aid. In response, some states developed pensions for veterans and public support for their families, reflecting an emerging sense of republican duty.30 Yet these measures remained exceptional; for the general poor, local governments continued to rely on old mechanisms, warning out, auctioning off the poor to the lowest bidder, and workhouse labor—as the default responses. The new American republic would inherit a system still largely rooted in British precedent, emphasizing localized, moralized aid rather than structural reform. As such, early American responses to poverty reveal both an evolving institutional landscape and a stubborn continuity in attitudes toward the poor.

Early American public welfare was a tool not only for assistance but also for social regulation. The systems that developed sought to contain and discipline poverty more than to alleviate it in any meaningful or systemic way. Relief was rarely sufficient to lift individuals out of destitution and often came with considerable loss of autonomy and dignity. The dichotomy between the “worthy” and “unworthy” poor entrenched a cultural stigma that would persist well into the nineteenth century.31 While both charity and public welfare provided a lifeline for some, they also reflected and reinforced the broader structures of inequality in early American society, structures rooted in class, race, gender, and power.

The American Revolution and the Changing Landscape of Poverty

The American Revolution transformed the political and social foundations of early American society, but it also disrupted longstanding economic systems, altering the contours of poverty in the new republic. Wartime inflation, destruction of property, and trade disruption disproportionately affected the working poor, many of whom had relied on subsistence farming or wage labor for survival.32 The cessation of British subsidies and access to imperial markets removed vital supports from colonial economies, while blockades and military campaigns ravaged local communities. Farmers lost livestock and crops, artisans lost markets for their goods, and thousands were displaced by the chaos of war. For the poor, these changes translated into greater material insecurity and fewer opportunities for stability. Revolutionary rhetoric promised liberty and equality, but the reality was a deepening of economic divides, particularly between landowners and laborers.33

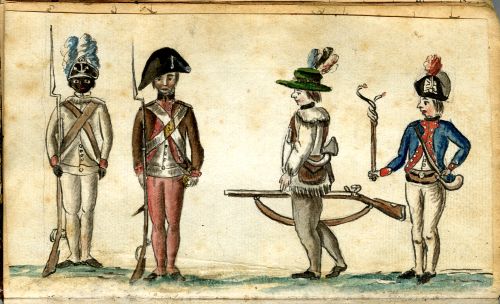

Veterans and their families bore a particular burden. While soldiers were hailed as heroes in public discourse, the support provided to them after the war often proved insufficient. Many returned home wounded or disabled, unable to work, and dependent on family or charity. Although some states and the Confederation Congress offered land bounties or pensions, disbursement was inconsistent and riddled with delays and corruption.34 Widows and children of fallen soldiers were frequently left without reliable support. This fostered frustration and disillusionment among many who had risked their lives for independence, contributing to postwar unrest such as Shays’ Rebellion in 1786–87. The revolution had mobilized the language of rights and justice, but in practice, the poor often found that their claims to those ideals were marginalized by the property-based definitions of citizenship and eligibility for aid.35

The war also exposed and intensified inequalities among marginalized populations. Enslaved people who escaped or were manumitted during the conflict, either by British forces offering freedom in exchange for service or by patriot masters moved by revolutionary ideals, faced precarious postwar conditions.36 Freed Black individuals in northern states encountered exclusion from skilled trades, limited access to land, and constant economic precarity, even as they were celebrated rhetorically as evidence of the Revolution’s moral progress. Native communities suffered catastrophic losses from military campaigns and the seizure of their lands, and many were pushed into deeper poverty as a result.37 Poor white Loyalists, meanwhile, often lost their property and were exiled or politically disenfranchised, with little compensation for their losses. These cases demonstrate how the Revolution’s effects on poverty were shaped not just by economic change, but by race, allegiance, and political power.

In urban areas, particularly in port cities like Philadelphia, Boston, and New York, poverty intensified after the Revolution as veterans, refugees, and displaced persons flooded into towns already struggling with resource shortages. Municipal governments and charitable organizations attempted to respond to the crisis, but they were hampered by limited funding and administrative capacity.38 The emergence of new charitable institutions (orphans’ homes, widows’ societies, and veterans’ relief committees) marked an evolution in the organization of poverty relief, blending republican ideals with older religious and moral traditions. Yet these institutions also inherited the same judgmental framework that had long dominated colonial welfare: aid was extended to those who conformed to prevailing ideals of industriousness, loyalty, and moral rectitude. Women continued to dominate the field of organized charity, reinforcing gendered patterns of poverty management even as political rights remained restricted to propertied men.39

In the broader context of the early republic, the American Revolution ultimately shifted the ideological framing of poverty without fundamentally resolving its structural causes. The notion of public responsibility for the poor evolved, particularly with regard to veterans and their families, but remained uneven and dependent on local initiative. The Revolution’s emphasis on individual liberty and self-sufficiency made Americans more wary of public dependence, even as economic hardship persisted.40 While some reformers began to call for more humane and rational responses to poverty, the prevailing belief in meritocratic success continued to shape attitudes toward the poor. Thus, the legacy of the Revolution was paradoxical: it expanded the rhetoric of rights and equality while simultaneously embedding new forms of exclusion and stigmatization into the fabric of the nation’s approach to poverty.

Conclusion

Poverty in early America was not an aberration but a persistent and structured feature of colonial and early national life. It was shaped by global economic systems, local labor practices, legal frameworks, and cultural attitudes. While early Americans developed various strategies to cope with and respond to poverty, their efforts often reinforced existing hierarchies and moralized economic failure. Understanding poverty in early America requires moving beyond romanticized visions of self-sufficiency and rugged individualism to confront the economic realities, systemic exclusions, and enduring inequalities that defined the period.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Allan Kulikoff, From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 98–102.

- Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: W. W. Norton, 1975), 143–47.

- Gloria L. Main, Peoples of a Spacious Land: Families and Cultures in Colonial New England (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 64.

- Gary B. Nash, The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979), 37–39.

- Ruth Wallis Herndon, Unwelcome Americans: Living on the Margin in Early New England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 21–25.

- Stephanie McCurry, Masters of Small Worlds: Yeoman Households, Gender Relations, and the Political Culture of the Antebellum South Carolina Low Country (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 18–20.

- Ira Berlin, Slaves Without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South (New York: Pantheon Books, 1974), 45–48.

- Woody Holton, Unruly Americans and the Origins of the Constitution (New York: Hill and Wang, 2007), 50–52.

- David W. Galenson, White Servitude in Colonial America: An Economic Analysis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 44–47.

- Kathleen M. Brown, Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 140–45.

- Tera W. Hunter, To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 9–11.

- Billy G. Smith, The “Lower Sort”: Philadelphia’s Laboring People, 1750–1800 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990), 37–39.

- Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788–1850 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 22–24.

- Carol Berkin, First Generations: Women in Colonial America (New York: Hill and Wang, 1996), 102–105.

- Richard L. Bushman, The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), 60–62.

- Linda K. Kerber, No Constitutional Right to Be Ladies: Women and the Obligations of Citizenship (New York: Hill and Wang, 1998), 23–25.

- Jeanne Boydston, Home and Work: Housework, Wages, and the Ideology of Labor in the Early Republic (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 56–58.

- Marylynn Salmon, Women and the Law of Property in Early America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 74.

- Karin Wulf, Not All Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000), 91–94.

- Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Good Wives: Image and Reality in the Lives of Women in Northern New England, 1650–1750 (New York: Knopf, 1982), 112–114.

- Deborah Gray White, Ar’n’t I a Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South (New York: W. W. Norton, 1985), 45–47.

- Cornelia Dayton, Women Before the Bar: Gender, Law, and Society in Connecticut, 1639–1789 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 142–146.

- Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 82–85.

- Herndon, Unwelcome Americans, 34-36.

- Michael B. Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: A Social History of Welfare in America (New York: Basic Books, 1986), 3–5.

- Perry Miller, The New England Mind: From Colony to Province (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953), 217–219.

- Anne M. Boylan, The Origins of Women’s Activism: New York and Boston, 1797–1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 42–44.

- David J. Rothman, The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic (Boston: Little, Brown, 1971), 45–48.

- Seth Rockman, Welfare Reform in the Early Republic: A Brief History with Documents (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2003), 18–20.

- Holly A. Mayer, Belonging to the Army: Camp Followers and Community During the American Revolution (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996), 165–167.

- Robyn Muncy, Creating a Female Dominion in American Reform, 1890–1935 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 3–5.

- Benjamin Carp, Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 139–142.

- Holton, Unruly Americans, 45-48.

- John Resch, Suffering Soldiers: Revolutionary War Veterans, Moral Sentiment, and Political Culture in the Early Republic (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 68–72.

- Wilentz, Chants Democratic, 29-31.

- Sylvia R. Frey, Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 182–185.

- Colin G. Calloway, The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 211–213.

- Nash, The Urban Crucible, 278-281.

- Nancy F. Cott, The Bonds of Womanhood: “Woman’s Sphere” in New England, 1780–1835 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), 88–90.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage, 1993), 273–275.

Bibliography

- Berkin, Carol. First Generations: Women in Colonial America. New York: Hill and Wang, 1996.

- Berlin, Ira. Slaves Without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South. New York: Pantheon Books, 1974.

- Boydston, Jeanne. Home and Work: Housework, Wages, and the Ideology of Labor in the Early Republic. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Boylan, Anne M. The Origins of Women’s Activism: New York and Boston, 1797–1840. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

- Brown, Kathleen M. Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Bushman, Richard L. The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

- Calloway, Colin G. The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Carp, Benjamin. Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Cott, Nancy F. The Bonds of Womanhood: “Woman’s Sphere” in New England, 1780–1835. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977.

- Dayton, Cornelia. Women Before the Bar: Gender, Law, and Society in Connecticut, 1639–1789. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

- Frey, Sylvia R. Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

- Galenson, David W. White Servitude in Colonial America: An Economic Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

- Herndon, Ruth Wallis. Unwelcome Americans: Living on the Margin in Early New England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

- Holton, Woody. Unruly Americans and the Origins of the Constitution. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007.

- Hunter, Tera W. To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Jones-Rogers, Stephanie E. They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

- Katz, Michael B. In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: A Social History of Welfare in America. New York: Basic Books, 1986.

- Kerber, Linda K. No Constitutional Right to Be Ladies: Women and the Obligations of Citizenship. New York: Hill and Wang, 1998.

- Kulikoff, Allan. From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

- Main, Gloria L. Peoples of a Spacious Land: Families and Cultures in Colonial New England. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Mayer, Holly A. Belonging to the Army: Camp Followers and Community During the American Revolution. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

- McCurry, Stephanie. Masters of Small Worlds: Yeoman Households, Gender Relations, and the Political Culture of the Antebellum South Carolina Low Country. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Miller, Perry. The New England Mind: From Colony to Province. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953.

- Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia. New York: W. W. Norton, 1975.

- Muncy, Robyn. Creating a Female Dominion in American Reform, 1890–1935. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Nash, Gary B. The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979.

- Resch, John. Suffering Soldiers: Revolutionary War Veterans, Moral Sentiment, and Political Culture in the Early Republic. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999.

- Rockman, Seth. Welfare Reform in the Early Republic: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2003.

- Rothman, David J. The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic. Boston: Little, Brown, 1971.

- Salmon, Marylynn. Women and the Law of Property in Early America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986.

- Smith, Billy G. The “Lower Sort”: Philadelphia’s Laboring People, 1750–1800. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990.

- Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. Good Wives: Image and Reality in the Lives of Women in Northern New England, 1650–1750. New York: Knopf, 1982.

- White, Deborah Gray. Ar’n’t I a Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South. New York: W. W. Norton, 1985.

- Wilentz, Sean. Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788–1850. New York: Oxford University Press, 1984.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage, 1993.

- Wulf, Karin. Not All Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.28.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.