Radicals

In 1800, very few people had the right to vote. Politics and the running of the government was limited to a small number of wealthy people. At the end of the eighteenth century, some people, later called radicals, questioned if this was the best method of government.

The most important radical writer at this time was Thomas Paine. Paine was born in Thetford and moved to America, where he played an influential role in drafting the Declaration of Independence. He later moved to France and became involved in the French Revolution, working with the leaders to produce the Declaration of the Rights of Man. Paine wrote a book called ‘The Rights of Man’ which said that everybody should have the right to be involved in government. His book sold half a million copies and was read by many more, passed around between groups of people and used as the discussion topic at political meetings.

Inspired by these ideas, groups of radicals formed corresponding societies in some larger towns. They began to meet at the same time that a revolution was taking place in France, during the late 1780s and the 1790s. The government in Britain was worried that these societies might start a revolution too. They became very concerned when the French revolutionaries executed their king. Many radicals were arrested and laws passed to ban corresponding societies and unions.

Thomas Hardy was a radical and the Secretary of the London Corresponding Society. It was the first radical group to be open to everyone. Their motto was that ‘our members be unlimited’. Hardy wanted to send a petition to Parliament in the hope that the political system would be reformed. Alarmed by the events in France and by the popularity of the London Corresponding Society, officials arrested Thomas Hardy in May 1794 for high treason. Shortly after his arrest, supporters of the government attacked Hardy’s house. The shock resulted in the death of his pregnant wife.

Luddites

The machine-breaking disturbances that rocked the wool and cotton industries were known as the ‘Luddite riots’. The Luddites were named after ‘General Ned Ludd’ or ‘King Ludd’, a mythical figure who lived in Sherwood Forest and supposedly led the movement.

They began in Nottinghamshire in 1811 and quickly spread throughout the country, especially to the West Riding of Yorkshire and Lancashire in 1812, and also to Leicestershire and Derbyshire. In Yorkshire, they wanted to get rid of the new machinery that was causing unemployment among workers. Hand weavers did not want the introduction of power looms. In Nottinghamshire, they protested against wage reductions.

Workers sent threatening letters to employers and broke into factories to destroy the new machines, such as the new wide weaving frames. They also attacked employers, magistrates and food merchants. There were fights between Luddites and government soldiers.

To catch the culprits, men were engaged to guard the factories and rewards were offered for information. The government sent thousands of troops to the areas where there had been trouble. In 1812, machine-breaking became a crime punishable by death and 17 men were executed the following year. The Luddites were very effective, and some of their biggest actions involved as many as a hundred men, but there were relatively few arrests and executions. This may be because they were protected by their local communities.

The disturbances continued for another five years. The crisis was made worse by food shortages as the price of wheat increased, and by the collapse of hosiery and knitwear prices in 1815 and 1816. Various attempts were made to find a compromise, but problems remained until the middle of the nineteenth century, by which time the woollen industry had moved away from hand-production.

There were many explanations put forward during the years of crisis and afterwards:

- The Luddites were not the first group of workers to face problems at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Some of the country’s economic difficulties were put down to the Napoleonic War (1802-1812), which disrupted trade between countries.

- The Luddites have been described as people violently opposed to technological change and the riots put down to the introduction of new machinery in the wool industry.

- Luddites were protesting against changes they thought would make their lives much worse, changes that were part of a new market system. Before this time, craftspeople would do their work for a set price, the usual price. They did not want this new system that involved working out how much work they did, how much materials cost, and how much profit there would be for the factory owner.

Peterloo

Between 1815 and 1819, there was a series of disturbances around Britain. Political meetings were held to protest to the government and to demand reforms. The climax came in 1819, when 60,000 people gathered at St. Peter’s Fields, Manchester. The main speaker at the meeting was Henry Hunt, a leading political reformer. The crowd gathered to hear Hunt speak about reform.

However, the local magistrates decided to arrest Hunt. They used the local yeomanry (part-time cavalry) to seize him. In the chaos that followed, eleven people died and many were injured. This event soon became known as ‘Peterloo’, after Britain’s recent victory at the Battle of Waterloo (1815).

Afterwards, there were different views about Peterloo. Some people blamed the magistrates; others cited the violence of the crowd. All sorts of people, including MPs, attacked the behaviour of the yeomanry, saying they were guilty of over-reacting because the meeting was peaceful. However, the government chose to defend the magistrates and the yeomanry. Then, to add insult to injury, the government introduced new laws to restrict political rights.

Captain Swing

In the eighteenth century, one of the main autumn and winter jobs for farm workers was threshing. This meant separating the grain from the stalks by beating it. In the late 1820s and early 1830s, farmers began to introduce threshing machines to do this work. This put large numbers of labourers out of a job and without the money to buy food, clothes and other goods for the winter months.

Low wages and unemployment, plus poor harvests in 1829 and 1830, resulted in hunger, protests and disturbances in many country areas, especially in the east and south of England. Farmers were sent threatening letters demanding that wages increase or at least stay the same. These letters often told farmers not to use threshing machines. Farmers and landowners also had their hayricks and farm buildings set alight.

The protesters used the name “Captain Swing”. This was a made-up name designed to spread fear among landowners and avoid the real protest leaders being found out.

The reaction of the government to the Swing disturbances was harsh. Following riots, 19 people were executed, 505 transported to Australia and 644 imprisoned. The story of individual incidents can often be put together from handbills and posters that offered rewards for the capture of rioters (and pardons for those who helped in their arrest). The labourers did not gain very much from their protests.

The Great Reform Act

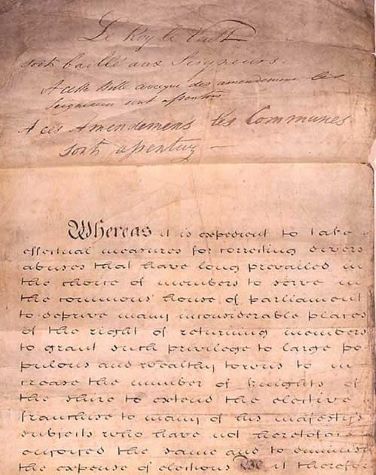

In 1832, Parliament passed a law changing the British electoral system. It was known as the Great Reform Act.

This was a response to many years of people criticising the electoral system as unfair. For example, there were constituencies with only a handful of voters that elected two MPs to Parliament. In these rotten boroughs, with few voters and no secret ballot, it was easy for candidates to buy votes. Yet towns like Manchester that had grown during the previous 80 years had no MPs to represent them.

In 1831, the House of Commons passed a Reform Bill, but the House of Lords, dominated by Tories, defeated it. There followed riots and serious disturbances in London, Birmingham, Derby, Nottingham, Leicester, Yeovil, Sherborne, Exeter and Bristol.

The riots in Bristol were some of the worst seen in England in the 19th century. They began when Sir Charles Weatherall, who was opposed to the Reform Bill, came to open the Assize Court. Public buildings and houses were set on fire, there was more than £300,000 of damage and twelve people died. Of 102 people arrested and tried, 31 were sentenced to death. Lieutenant-Colonel Brereton, the commander of the army in Bristol, was court-martialed.

There was a fear in government that unless there was some reform there might be a revolution instead. They looked to the July 1830 revolution in France, which overthrew King Charles X and replaced him with the more moderate King Louis-Philippe who agreed to a constitutional monarchy.

In Britain, King William IV lost popularity for standing in the way of reform. Eventually he agreed to create new Whig peers, and when the House of Lords heard this, they agreed to pass the Reform Act. Rotten boroughs were removed and the new towns given the right to elect MPs, although constituencies were still of uneven size. However, only men who owned property worth at least £10 could vote, which cut out most of the working classes, and only men who could afford to pay to stand for election could be MPs. This reform did not go far enough to silence all protest.

Chartists

In 1832, voting rights were given to the property-owning middle classes in Britain. However, many people wanted further political reform.

Chartism was a working class movement, which emerged in 1836 and was most active between 1838 and 1848. The aim of the Chartists was to gain political rights and influence for the working classes.

Chartism got its name from the People’s Charter, that listed the six main aims of the movement. These were:

- a vote for all men (over 21)

- the secret ballot

- no property qualification to become an MP

- payment for MPs

- electoral districts of equal size

- annual elections for Parliament

The movement presented three petitions to Parliament – in 1839, 1842 and 1848 – but each of these was rejected. The last great Chartist petition was collected in 1848 and had, it was claimed, six million signatures. The plan was to deliver it to Parliament after a peaceful mass meeting on Kennington Common in London. The government sent 8,000 soldiers, but only 20,000 Chartists turned up on a cold rainy day. The demonstration was considered a failure and the rejection of this last petition marked the end of Chartism.

Some opponents of the movement feared that Chartists were not just interested in changing the way Parliament was elected, but really wanted to turn society upside down by starting a revolution. They also thought that the Chartists (who said they disapproved of violent protest) were stirring up a wave of riots around the country. On 4 November 1839, 5,000 men marched into Newport, in Monmouthshire, and attempted to take control of the town. Led by three well-known Chartists (John Frost, William Jones and Zephaniah Williams), they gathered outside the Westgate Hotel, where the local authorities were temporarily holding a number of potential troublemakers. Troops protecting the hotel opened fire, killing at least 22 people, and brought the uprising to an abrupt end. Preston in Lancashire was the scene of rioting in 1842.

Support for Chartism peaked at times of economic depression and hunger. There was rioting in Stockport, due to unemployment and near-starvation, and Manchester, where workers protested against wage cuts, wanting “a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s labour”. The “Plug Plots” were a series of strikes in Lancashire, Yorkshire, the Midlands and parts of Scotland that took place in the summer of 1842. Workers removed the plugs from the boilers in order to bring factory machinery to a halt. Wage cuts were the main issue, but support for Chartism was also strong at this time.

Although the Chartist movement ended without achieving its aims, the fear of civil unrest remained. Later in the century, many Chartist ideas were included in the Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884.

The Match Girls

On 23rd June 1888, Annie Besant, a campaigner for women’s welfare and rights, published an article called ‘White Slavery in London’. She revealed the terrible conditions and poor wages suffered by the match girls employed at the Bryant and May factory in the east end of London.

The match girls worked long hours for very low wages, and could lose part of their wages in fines for such offences as arriving late or talking. Still worse, their working conditions were dangerous. The fumes from the white phosphorous used to make matches were poisonous. Workers could get necrosis or ‘phossy jaw’. It began with pain and swelling in the teeth and jaw, then foul-smelling pus formed. The jaw turned green and black as the bone rotted away and, without surgery, death could be the result.

Besant’s article gained a great deal of publicity because the Victorians believed that only ‘inferior races’ kept slaves. The British had banned slavery in 1833. To find out that women worked in such poor conditions in the match factories shocked respectable Victorians.

The factory owners were not pleased. They sacked the women who they suspected of talking to Besant. In response, Besant helped the rest of the women in the factory to form a trade union, which came out on strike. With the support of some of the press and the generosity of the public, money was collected to aid the striking women. Many people stopped buying Bryant and May matches.

At first, the owners of the factory stated that they would not take the strikers back into their employ. But on 21 July they gave in to the demands of the match girls, ended the fines system and re-employed those who had been sacked, ending the strike. However, it was to be many more years before they stopped using the dangerous phosphorous.

This was the first time a union of unskilled workers had succeeded in striking for better pay and working conditions. It inspired unions across the country. Within a year, the London dockworkers were on strike, confident that if the match girls could succeed, then so could they.

Suffragettes

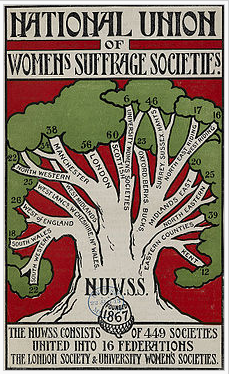

Throughout the nineteenth century, women played a prominent role in the fight for political rights. In the second half of the century, three major acts were passed extending political rights – but not to women. Women made only limited progress towards being able to control their own affairs and they did not have the right to vote.

Campaigns for equal voting rights did not become effective until the end of the century, when Millicent Fawcett formed the moderate National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. The NUWSS was based on a network of local suffrage groups, many of which had been created since the 1860s, when they had attempted to get women included in the terms of the 1867 Reform Act. They lobbied politicians, staged demonstrations and campaigned to get the support of the public for their cause.

The campaign gained an even higher profile through the actions of the Women’s Social and Political Union, formed in 1903 by mother and daughter Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst. The WSPU disrupted public meetings, broke shop windows, set post boxes and buildings on fire and staged noisy protests. When they were arrested, they went on hunger strikes.

The protesters often clashed with police and with the public. For example, at demonstrations outside the Houses of Parliament on 18 and 23 November 1910, there was violence and arrests. The police were accused of behaving with unnecessary brutality and the 18th became known as Black Friday. In 1913, the campaign stepped up and Emmeline Pankhurst was imprisoned for three years for her part in planning protests. On 4 June, Emily Davison was killed at the Epsom Derby.

However, protests were put aside as the women joined in the war effort between 1914-18. In 1918, women were able to vote in general elections for the first time.

Originally published by The UK National Archives under Crown CopyrightOpen Government Licensing.