He saw military strength as the means to achieve national greatness.

By Dr. Charles A. Stevenson

Adjunct Lecturer in American Foreign Policy

Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS)

Johns Hopkins University

Introduction

I will have no criticism of my Administration from you, or any other officer in the Army.

President Roosevelt to the Commanding General of the Army, 19011

If, during the years to come, any disaster should befall our arms, afloat or ashore … the blame will lie upon the men whose names appear upon the roll-calls of Congress on the wrong side of these great questions.”

GovernorRoosevelt in 1899 speech2

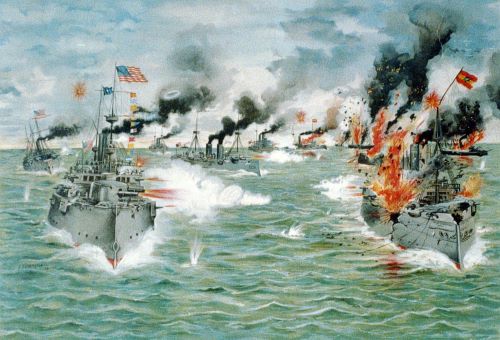

Moderate in stature but brimming with radical ideas and outsized ambition for himself and his country, Theodore Roosevelt entered the White House with firm views on how to strengthen the American military. He brought to the presidency a breadth of understanding and experience rare for a 42-year-old. As a student of history who wrote a well-regarded book on the naval aspects of the War of 1812, he appreciated the value of sea power and the advantages of technology. As the Assistant Secretary of the Navy in the year before the Spanish–American War, he understood the ways of Washington bureaucracy. As a member of the National Guard and later a Colonel in combat in Cuba, he knew the frustrations of logistics and the terror and exhilaration of battle.

The story of civil–military relations under Theodore Roosevelt is a tale of bold ideas, experimentation, foot-dragging, and partial success. The new president was determined to modernize and strengthen the US armed forces so that they could bolster his expansionist foreign policy. He wanted to take full advantage of the emerging technologies which American industrial might was providing. As an exemplar of a younger generation, the first post-Civil War political leaders, he insisted on reshaping US military institutions and elevating bright, if iconoclastic, younger officers. These laudable goals, however, met powerful opponents: senior officers resistant to change and a Congress comfortable with its role and reluctant to cede power to the upstart president.

A sickly child, embarrassed that his own father had avoided combat in the Civil War by hiring a substitute, young Theodore seemed fascinated by military things and ranked warlike qualities high in his table of virtues. He romanticized war, wished for war, and viewed peace “dull and effeminate”, as one biographer put it.3 Throughout his public service, he was a frequent commentator and vigorous advocate of US military strength and assertiveness.

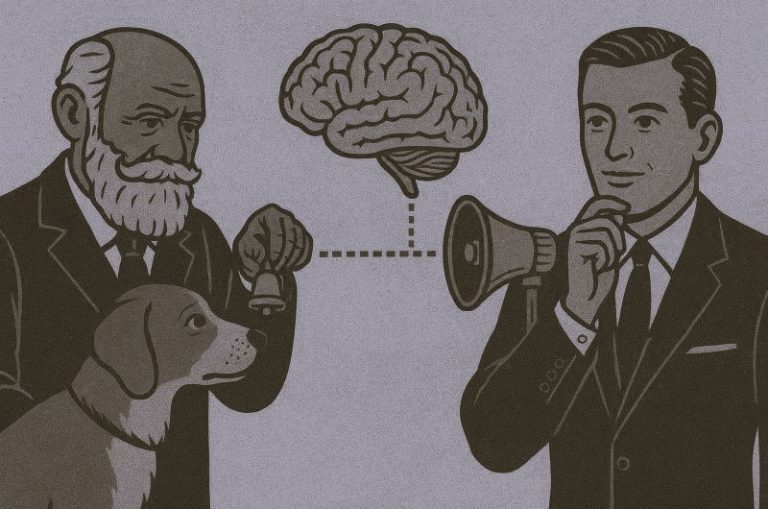

One of the clearest expositions of his philosophy was in a speech at the Naval War College soon after becoming the Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1897. In it he set forth a detailed agenda for the armed forces and propounded themes that echoed throughout his life. He saw military strength as the means to achieve national greatness.

- “In this country there is not the slightest danger of an over-development of warlike spirit, and there never has been any such danger.”4

- “This nation cannot stand still if it is to retain its self-respect.”5

- “[W]e need a first-class navy” that “should not be merely a navy for defense.”6

- “It is necessary to have a fleet of great battleships if we intended to live up to the Monroe Doctrine ….”7

- “No master of the prize ring ever fought his way to supremacy by mere dexterity in avoiding punishment. He had to win by inflicting punishment.”8

- “Diplomacy is utterly useless where there is no force behind it; the diplomat is the servant, not the master, of the soldier.”9

In subsequent speeches, Roosevelt embraced the imperialism of the European powers and urged Americans to follow those examples. “We are a great nation and we are compelled, whether we will or not, to face the responsibilities that must be faced by all great nations”, he declared. “Where we have won entrance by the prowess of our soldiers we must deserve to continue by the righteousness, the wisdom, and the even-handed justice of our rule.”10

He gathered around him men of ideas and accomplishment, often authors like himself. By 1890 he was in regular correspondence with other advocates of expansive nationalism and military preparedness like Alfred Thayer Mahan and Henry Cabot Lodge. They echoed and reinforced each other’s views, for they shared a common vision of America as a great power equal to the nations of Europe.11 They also succeeded in the political dialogue with the anti-imperialists and progressives who wanted America’s great national energies directed toward domestic reform.

Perhaps the most explicit articulation of his plans came, while he was still Governor of New York, in an April 10, 1899 speech to the Hamilton Club of Chicago, where he declared

that our country calls not for the life of ease but for the life of strenuous endeavor. The twentieth century looms before us big with the fate of many nations. If we stand idly by, if we seek merely swollen, slothful ease and ignoble peace, if we shrink from the hard contests where men must win at hazard of their lives and at the risk of all they hold dear, then the bolder and stronger peoples will pass us by, and will win for themselves the domination of the world.

In this speech, he also said “Our army needs complete reorganization – not merely enlarging – and the reorganization can only come as the result of legislation. A proper general staff should be established, and the positions of ordnance, commissary and quartermaster officers should be filled by detail from the line.”12

Roosevelt anticipated that such changes would meet opposition in Congress, which he said “has shown a queer inability to learn some of the lessons of the [Spanish–American] war.” He warned that “If, during the years to come, any disaster should befall our arms, afloat or ashore … the blame will lie upon the men whose names appear upon the roll-calls of Congress on the wrong side of these great questions.”13

The accidental president never doubted his abilities or his authority. “I believe in a strong executive; I believe in power”, he said.14 While he saw the necessity of working closely with the Legislative Branch on domestic issues, he felt differently about foreign policy. As he once told William Howard Taft, “You know as well as I do that it is for the enormous interest of this government to strengthen and give independence to the executive in dealing with foreign powers.”15 Never having served in a legislative body, he saw little need for compromise, particularly of his strongly held convictions. Yet he was a professional politician, who understood the necessity of building and maintaining, through consultation and patronage, a strong party organization.

Congress was comfortably in Republican control, but divided by sectional and substantive differences over Roosevelt’s programs. The House of Representatives during much of his presidency was under the iron rule of “Uncle Joe” Cannon, a domineering Speaker who ran a tight ship throughout the Roosevelt Administrations. The president met frequently with Speaker Cannon, who used his office as a clearinghouse to vet White House ideas. The Senate was controlled by “The Senate Four”, the powerful quartet of rich men – Aldrich of Rhode Island, Spooner of Wisconsin, Platt of Connecticut, and Allison of Iowa.16 They, too, met informally and worked collegially with the young president.

Reduced tariffs for products from Cuba and other newly acquired territories met the strongest congressional opposition, since tariffs were viewed as a domestic rather than foreign policy issue. When William Howard Taft, then governor of the Philippines, complained about Republican protectionists, the president strongly defended them. “With every one of these men I at times differ radically on important questions; but they are the leaders, and their great intelligence and power and their desire to do what is best for the government, make them not only essential to work with but desirable to work with. Several of the leaders have special friends whom they desire to favor, or special interests with which they are connected and which they hope to serve. But, taken as a body, they are broad-minded and patriotic, as well as sagacious, skillful and resolute.”17

This was a time when congressional committees fashioned budgets through direct consultations with the executive departments, without much involvement of the White House. While presidents might, as Roosevelt did, recommend revised laws and new battleships, the key initiatives and follow-through came from the cabinet members. The Legislative Branch took seriously its responsibilities to raise and support armies and provide and maintain a navy. And the Senate expected to give advice as well as consent to international agreements.

The Senate’s Military Affairs Committee was chaired by Joseph Hawley of Connecticut, who was close to Secretary of War Root since both had graduated from Hamilton College. Every member of that committee had served in the Civil War, eight Republicans who had fought for the Union and four Democrats who served in the Confederate army.18

US armed forces were rebuilding after decades of neglect and trying to adjust to the new strategic situation following the Spanish–American War, which left the United States in charge of overseas territories and confronting competitive military powers in Europe and Asia. The army in 1898 had been a dispersed and malcoordinated force of about 28,000 men. After surging above 200,000 to fight in Cuba, it was still an enlarged force of 85,000 when Roosevelt took the oath of office. The navy, even smaller than that of Austria–Hungary or Turkey a decade earlier, was gaining new, modern warships each year, provided by a generous Congress. The 3,600-man Marine Corps was seen as the navy’s onboard gunnery managers and offshore police force. It would soon grow into the navy’s army and be used repeatedly in military interventions in support of the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. It doubled in size by 1904 and was over 9,000 when Roosevelt left office.

Power Struggle

Senior officials waged nonviolent but vicious guerrilla war against each other in the early years of the twentieth century. The Commanding General of the Army, Nelson A. Miles, was a celebrated officer who was much-wounded and decorated during the Civil War and later led forces to triumph over such Indian leaders as Chief Joseph, Geronimo, and Sitting Bull. As the senior serving officer, he became Commanding General on the mandatory retirement of his predecessor in 1895. Despite its title, that post had little real power. The Secretary of War ran the quasi-independent bureaus of the army in peacetime, and the president named field commanders in wartime – as McKinley did in 1898, sidetracking Miles and letting Major General William R. Shafter command troops fighting in Cuba.

Tensions between the senior general and the Secretary of War had been so high, and so persistent, that two previous Commanding Generals had moved their headquarters away from Washington. Winfield Scott went to New York in the 1840s and William T. Sherman moved to St. Louis in 1874.19 Those absences, of course, only strengthened the civilian leader’s power over the rest of the army. The various bureaus were headed by permanently detailed staff officers, who were usually happy to escape the rigors of frontier life and relax in the comforts of the capital city.

Miles himself had strongly differed with Secretary of War Russell Alger over how to fight Spain. Miles vigorously opposed any attack on Havana, or any invasion of Cuba during the rainy season, and instead badgered his boss with his own plan for invading Puerto Rico first. He also objected to the Administration’s policy of accepting large numbers of volunteers for the war, fearing that the resources for training and equipping them would siphon away officers and supplies needed for immediate combat.20

Within days of the end of the fighting, Miles was giving interviews to the press with sharp criticisms of the War Department’s handling of the campaign. He complained that the Department had “mutilated and garbled” reports about the command issue and that it had suppressed his recommendation that US troops in Cuba be moved to healthy camps or evacuated to avoid disease. Back in the United States, he repeated his criticisms to a welcoming press corps. Despite speculation that he would likely be court-martialed for insubordination, Miles solidified his standing in public esteem by testifying, before the official Board of Inquiry investigating the war, about feeding the troops large quantities of what he labeled “embalmed beef.”21

Miles had political ambitions, hoping to be nominated – by either major party – for president. He even approached Roosevelt to suggest that the New York Governor be his Vice Presidential running mate in 1900. When Elihu Root succeeded Alger at the War Department, the new Secretary, though warned Miles would be difficult to work with, nevertheless tried to cooperate with him, at least at first. Root asked the general’s advice on officers to head volunteer regiments in the Philippines. Root wanted young and energetic officers but Miles recommended selection based strictly on seniority. The very next day, despite Root’s plea for secrecy in order to forestall an avalanche of applications, the matter surfaced in the press, and Root suspected Miles of the leak.22

Two days before McKinley was shot in Buffalo, Root wrote to the president complaining that Miles was trying “to promote his own views and undo my plans.” As McKinley’s successor, Roosevelt also had strong antipathies toward Miles, whom he had derided as “merely a brave peacock” in 1898. The commanding general later suggested in a public speech in 1901 that the then vice president had not even been at San Juan Hill.23 This further poisoned Miles’ relationship with Roosevelt.

The feuding pair had a shouting match at a White House reception in December 1901, after Miles had publicly criticized a navy board of inquiry’s finding in a dispute between two admirals. The general came to a White House reception to explain, and the president bellowed at him: “I will have no criticism of my Administration from you, or any other officer in the Army. Your conduct is worthy of censure, sir.” Responding “You are my host and superior officer”, Miles bowed and departed, but the resulting publicity was sympathetic to the general.24

Miles had cultivated good relations with members of Congress, and they came to his defense whenever Roosevelt contemplated ridding himself of the commanding general. One reason for Miles’ popularity on Capitol Hill was that he had resisted Root’s efforts to consolidate army posts throughout the country.25

In the subsequent months the president and Root compiled a record of Miles’ misbehavior. In one such memorandum from the White House in March 1902, Roosevelt wrote:

During the six months that I have been President, General Miles has made it abundantly evident by his actions that he has not the slightest desire to improve or benefit the army, and to my mind his action can bear only the construction that his desire is purely to gratify his selfish ambition, his vanity, or his spite.26

When Root advanced his proposal for a General Staff headed by a Chief of Staff early in 1902, Miles led the opposition. He believed he could administer the army without a staff and bragged that he had done that during the recent war without having to “get around a dozen or more majors.”27 Testifying before the Senate Military Affairs Committee, the commanding general noted that every member, like himself, was a veteran of the Civil War and then trashed Root’s plan as a revolutionary scheme that would abandon the lessons of history and “Germanize and Russianize the small Army of the United States.”28 He also doubted the wisdom of civilian control.

In fact, the general’s authority for initiative is taken away, and he can make no move without the direction or sanction of the all powerful General Staff, which, under the bill is subject to the control of the Secretary of War, whose knowledge of military affairs may be meager or nil.29

Miles’ comments on military inexperience were especially pointed, for Root, as a frail 17-year-old, had been rejected when he tried to enlist in 1865.30

The immediate impact of Miles’ testimony was so powerful that the committee chairman announced that no favorable action could be expected on the general staff bill that year. Miles continued his campaign against the administration by disclosing information about US atrocities in the pacification campaign in the Philippines. Roosevelt was tempted to remind the world that Miles’ troops at Wounded Knee had “killed squaws and children as well as unarmed Indians”, but reconsidered and pigeonholed his letter.31

Roosevelt was so incensed by Miles’ actions that he prepared papers to force the general to resign. “General Miles’ usefulness is at and end and he must go”, he wrote to a friend. But he also acknowledged: “It is a great question, upon which I must consult two or three of the leading members of the Senate and House, as to whether it will not be well to avoid complicating passage of the Army bill … by refraining from acting … until that is out of the way.” Several Senators defended Miles and urged the president not to oust the general, saying that it would cause another bitter controversy, stir up bad feeling in Congress, and be injurious to the Republican party in the coming Congressional campaign. Roosevelt relented, but later complained that “the only matter of importance in which I have sacrificed principle to policy has been that of Miles.”32

To assuage supporters of Miles, Root modified his proposal to provide that the serving Commanding General would become the first Chief of Staff, though in the end the law took effect only after Miles turned 64 in August 1903 and was legally required to retire. Root also got Miles away from Washington for several months, including the next winter session of the Congress, by sending him on an information-gathering trip to the Philippines, Asia and Europe.33

Meanwhile, Root launched a public relations campaign “to start a backfire.” He urged that several thousand letters be sent to members of Congress supporting army reorganization. He circulated articles to editors making the case for reform. He also arranged for supporting testimony before Congress from other retired generals, including Miles’ immediate predecessor as commanding general. Root even planted questions with key Senators to guarantee that the best arguments were aired.34

Early in 1903, with Miles circling the globe and public opinion more sympathetic, Congress passed the General Staff bill. The measure was the first of the four major modernization initiatives by the Roosevelt Administration, and it fulfilled the vision the New York Governor had articulated in 1899. But it came only after a severe challenge to civil–military relations from the nation’s senior military officer.

Reorganization

Secretary of War Elihu Root was already developing radical plans to reorganize the US Army when Roosevelt took office. The former New York lawyer had been named by President McKinley to fix the numerous problems evident in 1898 – such as sending the expeditionary force to Cuba clad in winter woolen uniforms – but he and Roosevelt had a longstanding friendship and a close convergence on ideas for the army. The commander of the Rough Riders called for “a thorough shaking up” of the War Department during the conflict in Cuba and later stressed to Root his belief in the need for substantial army reorganization.35

Root’s plan ultimately had four major features: (1) Creation of a General Staff for the army; (2) Abolition of the post of Commanding General, replacing it with a Chief of Staff directly under the Secretary of War; (3) Centralizing control of the various army bureaus under the Secretary and Chief of Staff; (4) Creation of an Army War College. All of these measures required legislation, and only the last met little resistance.

Knowing that he faced strong opposition from “officers who had become entrenched in Washington armchairs”, Root initially proposed only the elimination of future permanent details to staff bureaus and cutting such assignments to four years. After Congress accepted this change in 1901, Root began pushing the idea of a General Staff to do war plans and a War College to do studies and education. He also recommended making the senior general the Chief of Staff and abolishing the post of Commanding General.36

The navy went through a similar reorganization struggle, though it was less visible because there was no counterpart to the commanding general. Even more than the army, the navy was organized into fiefdoms – eight bureaus – run by long-serving officials. No one was tasked with planning for war. Finally, Secretary John Long, by a March 13, 1900 directive, took a partial step in the same direction as the army was taking by creating the General Board to advise him on strategy, war plans, and ship designs. He named the popular Admiral George Dewey as the first Board president.37 The US Navy did not acquire a senior officer and slightly less decentralized organization until the post of Chief of Naval Operations was created in 1915.

Long had wanted to have a general staff, but he ran into fierce opposition from inside and from Congress. The Chairman of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, Eugene Hale of Maine, denounced the idea, as did Long’s own deputy and most of the bureau chiefs. When Long’s successor, William Moody, decided to press ahead with a very modest general staff proposal, for what he described as a purely advisory body, he was defeated by overwhelming opposition. His own Assistant Secretary, Charles Darling, testified against the measure, saying “it savors too much of militarism.”38

Meanwhile, the Secretaries of the Army and the Navy moved to improve coordination between the Services by creating, in July 1903, the Joint Board. The new mechanism was born weak, however, lacking staff and prestige. It also fell into disfavor – and was sharply criticized by Roosevelt – when it failed to agree on the defensibility of Subic Bay in the Philippines in 1907. Nevertheless, it was a sign of the managerial revolution in American planning for war.

One effort at reorganization was particularly unsuccessful. Roosevelt, like many in the army, had little enthusiasm for the Marine Corps. Before becoming president, he had urged the amalgamation of the Corps into the Navy. He witnessed the service’s close ties to Congress and public opinion and later admitted privately that “no vestige of their organization should be allowed to remain. They cannot get along with the navy, and as a separate command with the army the conditions would be intolerable.”39 In his final year in office, Roosevelt ordered marines off ships, purportedly to free up men to form units to seize advance bases, but Congress, persuaded intellectually and politically, passed a rider countermanding the president’s order.40

Rejuvenation

Although the senior leadership in the military and in the Congress had wartime experience, it was dated. As late as 1901, every general officer in the army, line and staff, had first been commissioned before or during the Civil War.41 Roosevelt himself had complained that the navy began that war with 70-year-old captains, a fact he blamed on “the shortsightedness and supine indifference” of politicians who opposed reorganization efforts a half century earlier.42 Both services promoted by seniority rather than merit, and those long-serving officers had more reverence for the past than excitement about the future.

The youngest president preached – and practiced – “the strenuous life.” He wanted to elevate vigorous young men to positions of responsibility and authority. Not just in the military: he wanted the new territories to be administered by “only good and able men, chosen for their fitness, and not because of their partisan service.”43

Just as he had embraced civil service reform and merit promotions in his first Washington job, as one of three Civil Service Commissioners, Roosevelt sought to rejuvenate the armed forces by promoting bright young officers faster than their more pedestrian comrades. He said “our men come too old, and stay too short a time, in the high-command positions.”44 He also tried to reduce the line-staff distinction by trying to give talented staff officers line commands. This also generated opposition from those who stood to lose from such changes.

His military aides served as conduits for new ideas from the lower ranks, notably William Sims, who persuaded the president to overrule navy officials and impose a new means of continuous aim firing.45 He repeatedly asked Congress to allow merit promotions in the services but met with fierce opposition, in part because he elevated a disproportionate number of men from the cavalry compared to the other branches of the army. Eventually he allowed officers nearing retirement with 40 years of service to advance in rank upon retirement. He also began promoting promising young officers directly to brigadier general, nominating some 39 officers ahead of their seniors. In 1906, for example, he named Army Capt. John J. Pershing a one-star general. By 1907, however, congressional opposition had become so strong that Roosevelt stopped the practice.46

Roosevelt had a low opinion of old and overweight officers. Looking at his 300-pound commander in Cuba, Major General Shafter, Roosevelt told a friend that “men should be appointed as Generals of Divisions and Brigades who are physically fit.” Later as president, he tried to weed out the unfit by imposing tough new physical standards on the armed forces, ordering that each year navy officers walk 50 miles over three days and that army officers walk and ride horses for 90 miles over three days. When tired and blistered officers publicized their complaints, the president himself, with the press in tow, completed the army test in a single day!47

Technological Innovation

Roosevelt was an activist president, always in motion, filled with ideas, often impetuous. When it came to things military, he was often, in Matthew Oyos’ phrase, the “Chief Dilettante.” Soon after becoming president, he urged the army to switch from its traditional dark blue shirt to a more neutral gray or brown, which he argued would make a less obvious target. Later on, the president suggested that cavalry officers switch to a smaller spur, to make walking easier. In 1905 he launched campaigns to get the army to develop new, more efficient entrenching tools and to design improved bayonets for troops and swords for officers.48

Organizational innovation also captured the president’s interest. Advised by a friend from 1898 that the army was resisting a proposal to develop a separate machine-gun corps, Roosevelt intervened and ordered a pilot project in one cavalry regiment and recommended an increase in officers to command machine-gun units. Congress never approved the added slots, however, and the army itself resisted setting up a separate branch.49

Roosevelt’s most far-sighted efforts at technological innovation were focused on aircraft, submarines, and battleships. While in the Navy Department, he endorsed support for Samuel Langley’s experiments with heavier-than-air machines, which had broad political support in Washington but which crashed ignominiously into the Potomac River shortly before the Wright Brothers’ success. As president, he pushed the War Department to use discretionary money previously approved by Congress to fund three prototypes. Only the Wright Brothers delivered a usable aircraft, but its initial successes ended with a fatal crash in 1908.50

The US Navy also had been slow to embrace new technology. In 1869 it had unceremoniously decommissioned the fastest warship in the world, the Wampanoag, with a record not equaled until the 1890s, and the sea service continued to resist building ships without sails and with steel hulls and steam engines until the 1880s. As the officers who recommended scrapping the Wampanoag declared:

Lounging through the watches of a steamer, or acting as firemen and coal heavers, will not produce in a seaman that combination of boldness, strength and skill which characterized the American sailor of an elder day; and the habitual exercise by an officer, of a command, the execution of which is not under his eye, is a poor substitute for the school of observation, promptness and command found only on the deck of a sailing vessel.51

Eventually, however, the navy was forced to accept ironclad, steam-driven warships. There was also enthusiasm in Congress for submarines, both from representatives from shipbuilding districts and from those who viewed them as an alternative to expensive battleships. Roosevelt was so excited by the prospect of these new boats that in 1905 he secretly boarded one for a tour and nearly an hour of underwater operations. Having survived, he told the press of his adventures, which the New York Times trumpeted as “President Takes Plunge in Submarine.” He went on, as with the machine gun corps idea, to recommend more favorable pay and promotion treatment for submariners, who tended to be disparaged and discriminated against by the rest of the navy.52

Besides seeking more and bigger battleships, Roosevelt endorsed the idea of an all big-gun ship even before the British Dreadnought demonstrated the value of such a design and, in a single stroke, rendered all existing warships obsolete. In this case, the president sided with his naval aide, then commander William Sims, and against his friend and naval sage, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan. When Sims and others later criticized the design of the new North Dakota class battleships, Roosevelt largely ignored their views in order not to delay construction.53

Expansion

The military program with Roosevelt’s most ardent and consistent support, and the most ultimate success, was increasing the size of the armed forces, especially the fleet. A large modern navy was essential to his vision of great power America, particularly since the nation now had to defend overseas territories in the Pacific and the sea lanes to the forthcoming Panama Canal.

When Roosevelt was Assistant Secretary of the Navy, the fleet was rapidly growing and had reached sixth in overall strength compared with other nations, with its first generation battleships, the Maine and Texas, and three fully modern ones. By the time he entered the White House, the US Navy ranked fourth in the world, with nine battleships at sea and eight more authorized or at some stage of construction. When he left office, there were 25 battleships and ten heavy cruisers in commission and two more battleships finishing construction. Only Britain had more capital ships, though Germany had more tonnage.54

He did not get all he asked for, or when he asked for it, because Congress had its own ideas about timing and affordability. The biggest fight was in 1907, when Congress cut the president’s request for four additional battleships in half, with even the naval affairs committee chairman lukewarm to the idea.55 Some legislators still resisted the costs of the military buildup, but few questioned Roosevelt’s standard – to have a fleet as large as any competitor other than Britain.

Navy personnel also increased dramatically during Roosevelt’s presidency, rising from 20,900 in 1901 to 47,533 in 1909. But even these numbers fell short of the manning needs of the larger, more complex steamships.

Despite Roosevelt’s antipathy toward the Marine Corps, it also grew by 65 percent while he was in the White House, from 5,865 to 9,696. The army was about 84,000 at the beginning and end of his term, but it declined during his presidency to a low point of 64,000 in 1907.56

Resistance to Modernization

Roosevelt had an agenda for change for the US military, for change in organization, size, technology, and personnel. His motives were many – the goal of national greatness, the measure of merit in military power, a projection of ideas of manly virtue onto the global stage. He was strikingly successful in much of what he tried, but only after surmounting the predictable and recurring roadblocks to military transformation.

Innovation is particularly difficult for military organizations. A successful, war-winning force has no incentives to change, or even to risk unforeseen problems by altering its existing ways. Advocates of the status quo feel threatened, either directly by the loss of position or prestige, or indirectly by the prospect of uncertainty and adjustment. To impose change on reluctant military services, therefore, requires a strong advocate, supportive allies, adequate resources, and patience.

In most but not all of his efforts, Theodore Roosevelt served as that strong, steady advocate. Sometimes he lost interest or became preoccupied with other ventures, as one would expect of a hyperactive president who faced numerous domestic and international crises.

The opposition was predictable – from the officers “entrenched in their armchairs” and from Members of Congress who believed they had a preeminent Constitutional role in shaping the US armed forces and who had political incentives to support particular programs, whether or not they were consistent with the president’s proposals.

Where funds were required – or new laws – the Legislative Branch had the ultimate power. But where executive discretion was available, Roosevelt acted forcefully – such as in ordering tougher physical fitness tests and in sending the Great White Fleet halfway around the world, and daring Congress to fund its return.

Civil–military relations under Theodore Roosevelt were no more strained than usual, for many in uniform welcomed his efforts to remove deadwood from on top and embrace new technology, despite the griping of those uncomfortable with the changes. Congress was also more often than not an ally of the president, funding his expansion of the fleet, even if not as fast as the president wished, and sharing his views on the need for a stronger military to play a global role.

Endnotes

- Edmund Morris, Theodore Rex, New York, NY: Random House, 2001, p. 79.

- Mario R. DiNunzio, Theodore Roosevelt: An American Mind: A Selection from his Writings, New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1994, p. 187.

- Howard K. Beale, Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 1956, pp. 36–7; Edmund Morris, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, New York, NY: Ballantine Books, 1979, pp. 38–9.

- DiNunzio, p. 173.

- DiNunzio, p. 178.

- June 2, 1897 speech, quoted in DiNunzio, p. 176.

- DiNunzio, p. 177.

- DiNunzio, pp. 176–7.

- DiNunzio, p. 177.

- Speech February, 1899 as NY Governor to the Lincoln Club dinner, quoted in DiNunzio, pp. 180–3.

- Beale, p. 22.

- DiNunzio, pp. 189 and 187.

- DiNunzio, p. 187.

- John Morton Blum, The Republican Roosevelt, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Second edition, 1978, p. 107.

- Alvin M. Josephy, Jr., On the Hill, New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1979, p. 283.

- Robert C. Byrd, The Senate: 1789–1989, Addresses on the History of the United States Senate, Washington, DC: GPO, 1988, p. 37.

- Quoted in Stephen Skowronek, The Politics Presidents Make: Leadership from John Adams to George Bush, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993, p. 239.

- Edward Ranson, “Nelson A. Miles as Commanding General, 1985–1903”, Military Affairs 29, no. 4, Winter, 1965–6, p. 194.

- Ranson, p. 182.

- Ranson, p. 184.

- Ranson, pp. 187–8.

- Ranson, p. 190; Philip C. Jessup, Elihu Root, Vol. I, 1845–1909, New York, NY: Dodd, Mead, 1938, pp. 244 and 245.

- Jessup, pp. 244–5.

- Morris, Theodore Rex, p. 79.

- Russell F. Weigley, History of the United States Army, New York, NY: Macmillan, 1967, p. 319.

- Jessup, pp. 245–6.

- Philip L. Semsch. “Elihu Root and the General Staff ”, Military Affairs, 27, no. 1, Spring, 1963, p. 21.

- Ranson, p. 194.

- Otto L. Nelson, Jr., National Security and the General Staff, Washington, DC: Infantry Journal Press, 1946, p. 54.

- Warren Zimmerman, First Great Triumph: How Five Americans Made Their Country a World Power, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002, p. 124.

- Nelson, p. 54; Morris, Theodore Rex, p. 97.

- Ranson, pp. 195 and 195n.

- Ranson, p. 197.

- Semsch, p. 20; Jessup, p. 261.

- Oyos, 2000, p. 317.

- Nelson, pp. 47–52.

- Kenneth J. Hagan, This People’s Navy: The Making of American Sea Power, New York, NY: Free Press, 1991, p. 232.

- Henry P. Beers, “The Development of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations”, Military Affairs 10, no. 1, Spring 1946, pp. 58 and 54.

- Quoted in Matthew M. Oyos, “Theodore Roosevelt, Congress, and the Military: U.S. Civil–Military Relations in the Early Twentieth Century”, Presidential Studies Quarterly 30, no. 2, June 2000, p. 316.

- Oyos, 2000, p. 317.

- Arthur P. Wade, “Roads to the Top: An Analysis of General-Officer Selection in the United States Army, 1789–1898”, Military Affairs 40, no. 4, December 1976, p. 162.

- DiNunzio, p. 175.

- DiNunzio, p. 189.

- Quoted in Oyos, 2000, p. 322.

- Elting E. Morison, Men, Machines, and Modern Times, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1974, pp. 28–31.

- Mathew M. Oyos, “Theodore Roosevelt and the Implements of War”, Journal of Military History 60, October 1996, p. 636; Oyos, 2000, pp. 322–3.

- Zimmerman, p. 275; Oyos, 2000, pp. 323 and 324.

- Oyos, 2000, p. 313; Oyos 1996, pp. 635–7.

- Oyos 1996, pp. 63–9.

- Oyos, 1996, pp. 640–1.

- Morison, pp. 114, 98–9 and 116–7.

- Oyos 1996, pp. 642–4.

- Oyos 1996, pp. 645–9.

- Walter Millis, Arms and Men, New York, NY: New American Library, 1956, p. 172n; Hagan, p. 240.

- Harold and Margaret Sprout, The Rise of American Naval Power, 1776–1918, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1944, p. 267n.

- Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, Washington, DC: Department of Commerce, 1975, p. 1141.

Chapter 8 (139-151) from Warriors and Politicians: US Civil-Military Relations under Stress, by Charles A. Stevenson (Routledge, 07.13.2006), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.